Lincoln Barrett’s musical journey started in the box, but 20 years on, he’s reinventing his trademark liquid funk sound with vintage hardware.

Inspired by the original pioneers of jungle and drum & bass, Lincoln Barrett (aka High Contrast) found his own way into production. Since signing to Hospital Records in 2000, he has become one of the genre’s biggest names. Drawing on an early obsession with film soundtracks and sound design, he developed a signature liquid funk sound, pumping out anthems with epic vocals and drum & bass remixes of household names like Adele, Kanye West, White Stripes and Coldplay. Even nowadays, a new High Contrast track just has to be premiered on BBC Radio 1 on a Friday night for audiences to be singing the track back as he DJs the next day in a massive club. His recent album Restoration is heavily inspired by the old Roland and Akai hardware samplers used by the hip‑hop pioneers.

Sound & Vision

“I had no interest in music until I was about 16,” admits Barrett. “Certainly not contemporary music. I was interested in film from the earliest possible age, so I collected film soundtracks. My sister got me Goldie’s Timeless album and I thought ‘What the heck is this?!’ I’d never heard jungle before. It was the most alien thing, and I couldn’t get my head round it. So I was immediately turning it off but kept going back to it, trying to work out exactly what this music was. Hearing those cut‑up, sped‑up drum loops being edited with a lot of sound effects. I also noticed there were sounds in there that I recognised from films, and then the strings were quite cinematic and haunting. But there was no context to it for me, I was coming at it completely blank.

“When I was 16 I went to college, and friends I met there were already into jungle and buying vinyl. I realised there was this whole scene where people are making music, often in bedrooms with very simple setups, and they’re sampling films that I love, and people are actually dancing to it. I felt this was tailor‑made for me, because the one thing I do know about is movies.

“At the same time, I got a free CD‑ROM on the cover of a computer magazine with a demo version of Cubase. I didn’t know anything about music production, but it did allow me to throw some samples together and start very basic explorations of making drum & bass. This was all at the start of the Internet, so I was able to download things like the Amen break and bass sounds but there was no real sense of an online community around drum & bass for me.

“It was only when I was 18 and I was able to actually get into clubs that I heard sub‑bass for the first time! Back then the sub‑bass was just pure sub 808, so there was no way I was going to hear that on my home stereo system. I think that has stuck with me, because I focus more on the melodies, the samples and the sounds rather than the bass and even the drums sometimes. That’s kind of my contrarian approach to things within drum & bass. I actually try and de‑emphasise the drums and bass element!”

Out Of Step

“I started very basic production around 1996, 1997 without any help from anyone. It took me a long time to figure out what I was doing, but by around 2000 my tunes were starting to sound... not professional, but they were sounding interesting, I think because drum & bass was so dark at that time. There was the whole techstep era in the late ’90s and I really didn’t connect with that. At the same time, I started to listen to house music, specifically Chicago house, the deep house sound, and New York garage. I loved all those sounds. At the same time there was Daft Punk happening and the whole French filtered house thing, which I loved. And I fell in love with disco. I wondered, why aren’t we getting this in drum & bass? So it kind of became my mission to try and do that whilst also tying it in to hip‑hop — the way you would have those funk, jazz and soul samples in hip‑hop.

“I was studying film at university but the music took over my life. I was being very prolific, knocking out track after track and honing the craft. It wasn’t club‑ready so people didn’t want to sign it, but they could see that I was making this kind of groundbreaking stuff. The liquid funk movement was starting to happen, as pioneered by DJ Fabio. Then it just so happened that London Electricity played in Cardiff and they ran Hospital Records. I gave them a demo when they played at the club because I was a resident DJ at the club. We just hit it off because I was playing soulful drum & bass and they were too. They listened to the demo and then they just rang me up and said ‘We want to sign you for an album deal.’ Going from a complete unknown to getting signed for an album was just fantastic.

“That immediately threw me into the scene, getting my stuff out on vinyl. Then that led to gigs and doing my first international gigs, and that led to a residency at Fabric and then getting played on Radio 1 by Fabio. It all happened very quickly off the back of that. And I also like the fact that they signed me for an album, because usually in dance music, and especially in drum & bass, the focus is on singles.”

Learning By Doing

At the same time, Barrett was still teaching himself the art of production. “I guess it’s good to have mentors and people, but I think nothing can beat figuring stuff out yourself and finding your own way of working. Like my first album. The production was very raw, some of the tracks could barely get mastered, because the production was so raw. But it just reinforces my philosophy, which is: if the ideas are good enough and if it makes you feel something powerfully enough, then the production almost doesn’t matter.

“The way I look at it is I don’t actually make songs, but I make things that kind of have the impression of a song. There are a lot of people making drum & bass now who are getting full vocals and it’s proper song structure. But I’m more interested in repetition and loops, finding the moment of something that I love, and repeating that. I would say it’s somewhere in between like proper songs and what other people normally do in drum & bass.

Restoration is High Contrast’s seventh album, and leans heavily on vintage sampling technology.“I think the other thing that creates that distance from normal songwriting is that I love vocals, but I try and use them just as another element in a track, and not give them the kind of dominance that a proper song would have. I treat the vocal as if it’s a Rhodes keyboard or the bass. There’s been some repeat uses of vocalists over the years, but generally I’m trying to find a new sound each time. But the majority of what I do is sample‑based, so that I’m sampling a track first of all, whether that is an a cappella or from a full song. Back in the day, I had to find creative ways of isolating a vocal sample from the rest of the song, whereas today, there are AI tools that will take vocals out for you cleanly. So most of what I do starts off as a sample of something else, and then I will get a vocalist who can accurately recreate it. So that is usually the determining factor.

Restoration is High Contrast’s seventh album, and leans heavily on vintage sampling technology.“I think the other thing that creates that distance from normal songwriting is that I love vocals, but I try and use them just as another element in a track, and not give them the kind of dominance that a proper song would have. I treat the vocal as if it’s a Rhodes keyboard or the bass. There’s been some repeat uses of vocalists over the years, but generally I’m trying to find a new sound each time. But the majority of what I do is sample‑based, so that I’m sampling a track first of all, whether that is an a cappella or from a full song. Back in the day, I had to find creative ways of isolating a vocal sample from the rest of the song, whereas today, there are AI tools that will take vocals out for you cleanly. So most of what I do starts off as a sample of something else, and then I will get a vocalist who can accurately recreate it. So that is usually the determining factor.

“For me, it’s finding someone who sounds like the the existing sample. And that’s a very specific skill set. Not every vocalist wants to do that. There are people who specialise in that and there’s a company called Replay Heaven who are just incredible at recreating samples and do it to a world‑class degree, to the point where often I think the recreations actually sound better than the original samples. Doing it that way, I also get the stems of the sample. So I have so much more freedom in exploring that musical idea than if it was just the sample. Sometimes I will, however, maintain it as the solid sample to keep the integrity of the idea of sampling. I think sometimes that limitation of just having the sample and not having the separate stems has a particular sound in itself. I am a believer in limitations as being actually essential to creative processes.”

Coming Around Again

Restoration is the seventh High Contrast album, and marks a conscious return to Barrett’s roots. “At the outset, the Restoration album was me wanting to get back to basics and go back to the liquid funk sound that was introducing those soulful and house elements to drum & bass. I always wanted to come back to this liquid sound, but I knew I needed to leave enough time. I think 20 years is actually a good amount of time when it comes to cycles within music. I think it’s enough time that there’ll be a new generation of listeners who aren’t aware of the original sound.”

Lincoln Barrett: I built my whole career on sampling and yet I’d never used a sampler!

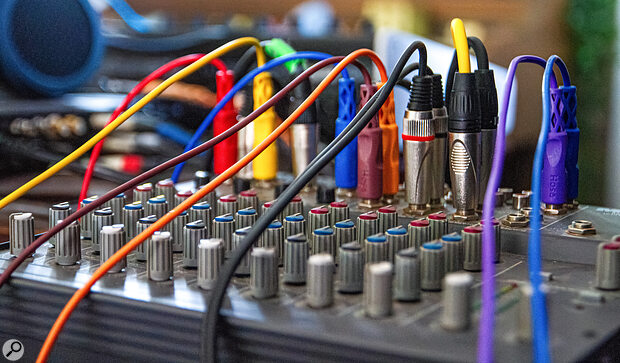

The album also saw Barrett take an old‑school approach to production — which, ironically, wasn’t the approach he took first time around. “When I started out, 25 years ago, I was all in the box and I didn’t use any hardware. Still to this day, I’ve never used a proper mixing desk. I have a little mixer but I’m not using it for mixing. It’s just literally to colour the sound, running the whole mix through it. It wasn’t until almost 10 years into releasing music that I bought one synth that I occasionally used. So it’s relatively recently that I’ve started to get more into using hardware, outboard gear and things like guitar pedals, as a way of challenging myself and wanting to try something different with my production. I built my whole career on sampling and yet I’d never used a sampler! It was a eureka moment about six years ago when I thought I should really get a sampler and have a go with that, because I love sampling. And so then that’s started a whole process and chain of events with getting into different samplers.

“I got an old Akai S950 that would have been used in the early days of jungle and drum & bass. I was going back to the roots of trying to get that sound. I like the sonics you get from it, even though using floppy drives is painfully slow. So I started looking at other samplers and I got the Isla S2400, which is a new recreation of the old E‑mu SP‑1200. The SP‑1200 was something I was very interested in getting, because Daft Punk used it on their first few albums, and of course it was used for lots of classic hip‑hop. But it’s really expensive. People I know who already had one said it was painful using it. It’s slow with the disks and you only have two seconds’ sample time. So that put me off it. With the S2400, you’ve got all the modern conveniences of USB connections and much longer sample time, but it does have the 12‑bit, 26kHz sample rate, so you do have that authentic old sound from the SP‑1200, where you get the aliasing on the samples and that lo‑fi quality.

For many years, Lincoln Barrett created music entirely in the box. When he decided to embrace hardware, he chose Isla Instruments’ modern recreation of the classic E‑mu SP‑1200 as his main sampler.

For many years, Lincoln Barrett created music entirely in the box. When he decided to embrace hardware, he chose Isla Instruments’ modern recreation of the classic E‑mu SP‑1200 as his main sampler.

“So, I started making hip‑hop beats on this sampler. I was very influenced by people like DJ Premier, RZA and ’90s hip‑hop. It made sense to me to make this liquid funk drum & bass album using this sampler, as it ties in with the hip‑hop feel and the French house thing as well. Having that as the focus of the album helped galvanise it and give it a particular sound and a direction for me to go in.

“I wanted to keep it sample‑based because I think in the digital age, you’re fighting against infinity. So I was trying to take the approach of making tracks with as few individual tracks as possible, and building things around a sample. I’ve got the sample: how many ways can I mess with this sample across the length of a piece where it feels interesting and the track is evolving? But I’m not actually adding new things to the track. Instead of ‘Here comes the string section!’ or a synth solo, I was trying to take a sample and then blow it apart to little pieces and rearrange it to try and find new sections for the song. J Dilla was the master of doing that.”

Ideas Man

Barrett’s writing process is unusual for the genre in that it’s somewhat ‘top down’. “I think most people in drum & bass start a track by building the drums and then the bass line, and then it seems that other elements such as a vocal or the melodic parts are almost an afterthought, in response to the growing base. I mean, it does make sense because the genre is called drum & bass! So I’m not knocking that approach. But for me, I don’t think I’ve ever made a track where I started with the drums or bass. For me, it’s always the musical idea that is the key. I try and make the drums and the bass fit around the musical idea and complement it. A lot of the time I’m using sampled drum breaks. I love the texture of them, there’s just something magical about the sound of those ’60s and ’70s drum breaks from the funk and soul records. There’s something about the recording of those drums. There is a reason why they have been used so much in hip‑hop and drum & bass, and that people still use the Amen break to this day, because it’s lightning in a bottle. It’s magic.

“For this album specifically, what with it having this sampled feel and a lot of soul samples, it just made sense to go back and use some of those classic drum breaks. But I am layering those with one‑shots. There’s generally at minimum 10 drum tracks on one of my songs. To get the weight that you need in a drum & bass track, especially at the moment, it does need this kind of very careful balancing of drum layers and a lot of saturation. Clipping basically has become the name of the game. Everything is clipped to the nth degree to squeeze every bit of loudness out of it. I try not to push it to the point where it sounds uncomfortably squashed. I try and get the balance where it still feels kind of pleasant to listen to, but then also has the weight where it will compete with other drum & bass tracks in a DJ set.”

Although hardware samplers have become central to the High Contrast production approach, software is also important. “I am generating ideas sampling vinyl or my little modular rig into the Isla S2400 sampler, usually at the classic lo‑fi setting of 26kHz/12‑bit. Once I have a groove or main loop, I record it into Ableton Live via the Prism Sound Lyra 2 interface. After adding drums and bass in Ableton and doing some arranging and processing, I’ll often then send the sampler recordings and other parts made in the DAW back out via the Lyra into my patchbay, where I run the audio through some effects, which is often another sampler like the Roland SP‑303 or the Zoom Sampletrak, which are both handheld devices from about 25 years ago and have great effects, or through guitar pedals or a Roland Space Echo. This signal then goes back through the Lyra into Ableton.

This small mixer is used mainly to colour the sound, rather than for mixing in the conventional sense.

This small mixer is used mainly to colour the sound, rather than for mixing in the conventional sense.

“With vocal recordings, I find the takes I want to use in Ableton and then send them to the S2400 where I lower the quality to 26kHz/12‑bit and usually do any pitch‑shifting I want there. I find the pitching done by hardware to be sonically more pleasing most of the time than doing it in a DAW. Then I run that through maybe the echo unit, either with delay or dry just for some saturation, and record that back into Ableton. Once the track is basically done, the main mix will likely get a pass through my little Mackie 1202 mixer for a touch of saturation. There might be an irony in using something as high fidelity as the Lyra interface when I’m using samplers at really lo‑fi settings, but my philosophy is that I want to record at the highest possible quality, even and especially when the audio source is very lo‑fi, because then the sound of the original gear is preserved and the audio is coloured as little as possible by the recording process. This feels important when going back and forth between hardware and software, potentially multiple times.

“If I’m cutting up a melodic sample on the sampler, I’ll record in the pattern that I’ve played on the sampler so that it’s recorded as audio. Then it’s like having a guitar performance and I can tweak it from there. Working with recordings of sampler patterns is a good way of making me commit to an idea.

“I am wary of nostalgia and being too tied to the past, and I’m not interested in just recreating the past, but I think we can take things from the past and try and reimagine them for today. I think you have to respond to the moment you are in as well, you know? So I like to kind of come up with these rules or limitations for making things. But at any given moment, I’m willing to abandon the rule if I think a better idea comes along. I guess I have my cake and eat it, because I’m using old samplers and some old things. But then, if something’s bothering me, I’ll fix it in Ableton or use some high‑tech tool. I am fine with that because it’s the end product that is the most important thing. At the end of the day, nothing beats your ideas, your emotional responses to things.

Since embracing hardware, Lincoln has built up a small collection of units including (from top) Pioneer SR‑202W spring reverb, Samson patchbay, Alesis Microverb reverb, Oberheim Matrix 1000 and E‑mu Vintage Keys synths, Alesis 3630 and SSL compressors and Louder Than Liftoff Silver Bullet preamp.“When you’re doing something outside of the historical moment, it’s just not going to hit in the same way. Like you know, when Daft Punk were doing that side‑chain house thing, 20‑odd years ago, that was new and exciting and it was something that naturally happened through their process. But like now kind of fetishising it and recreating it, it’s like, well done. You’ve made something that sounds exactly like Daft Punk from 25 years ago. So that’s kind of like my thing with jungle. I’m playing with those ideas, but it is also me today making something and hopefully it has my personality in it and whatever historical moment I’m in.”

Since embracing hardware, Lincoln has built up a small collection of units including (from top) Pioneer SR‑202W spring reverb, Samson patchbay, Alesis Microverb reverb, Oberheim Matrix 1000 and E‑mu Vintage Keys synths, Alesis 3630 and SSL compressors and Louder Than Liftoff Silver Bullet preamp.“When you’re doing something outside of the historical moment, it’s just not going to hit in the same way. Like you know, when Daft Punk were doing that side‑chain house thing, 20‑odd years ago, that was new and exciting and it was something that naturally happened through their process. But like now kind of fetishising it and recreating it, it’s like, well done. You’ve made something that sounds exactly like Daft Punk from 25 years ago. So that’s kind of like my thing with jungle. I’m playing with those ideas, but it is also me today making something and hopefully it has my personality in it and whatever historical moment I’m in.”

Forward Motion

Drum & bass as a genre has demonstrated an impressive ability to survive and evolve without losing its distinctive qualities. To conclude, I asked Lincoln Barrett where he sees it developing in the future. “Since the lockdowns, there’s been a real explosion of female DJs. It’s great to see that things have opened up because it did feel like such a boys’ club for so many years. I think it can only be good for the continuation of the genre that we have more diverse voices in it. There are people who have blown up from those lockdown streams and now have careers as DJs. I think we still need more female producers coming through. It’s great that there’s EQ50 [a collective of women working towards fairer representation within drum & bass] doing their mentorship schemes.

“I don’t know if it’s even possible, but I’m interested in what other ways of working can there be. Traditionally, dance music is made by one person working alone, just focused on that one task. Can the whole approach to music be reimagined? That’s what I would like to see from the new blood. Different perspectives. I’m an old man now, so I’m quite stuck in my way of working in isolation. But I don’t think everyone actually enjoys that. I’m intrigued to see if people can invent their own way of making music, maybe in a more collaborative way or something. That could be a path that leads to new sounds and maybe new genres. And I guess technology would be aiding that.

“The AI question is going to be a major thing to consider, just seeing how that plays out. If people can just type ‘High Contrast’ into an app and they get hundreds of tracks generated that sound like me, it could mean that we will be stuck with generating existing artists and no one can break through. Or maybe people will completely reject AI‑generated music because on some incalculable level, it just lacks the humanity that people can connect with. I really don’t know how all that is going to play out. I have no problem with AI tools, because they are being used in service of the human trying to create something. But when you’re delegating everything to a large language model to create something for you from a text input, that’s just less interesting to me. At the moment, it still feels like the AI music I’ve heard is just not good enough.”

Remixing

At the time of writing, Lincoln Barrett has just finished remixing his Restoration album into what he describes as a “lofi hip‑hop‑style mixtape”, and says that “Remixing is fun to me, because the hardest part has been solved. If you love the original song, then you’ve already got a great melodic idea there, so it’s just fun then playing around with that and arranging it. I’m not sure what the total count is, but it is a big part of what I do. I almost approach everything as a remix, because I’m sampling so much that you could argue that my original tracks are remixes in some way. Especially in my early productions, when I was just learning the craft, I was effectively remixing songs.

“One of the huge appeals of drum & bass to me was the drum & bass remixes of non‑drum & bass based songs. The big one for me was DJ Zinc’s bootleg remix of the Fugees ‘Ready Or Not’ [1996, white label]. That track just blew my mind when I heard it, it was so magical especially because it was a bootleg. I loved the original Fugees track, but then this drum & bass version took it to another level. I really struggle remixing drum & bass tracks, so I almost always turn them down now, because a big part of the appeal to me is taking something from another genre and turning it into drum & bass. Again, I like that contrast of pop with drum & bass.

“Drum & bass still is quite an abrasive music. A lot of people just cannot handle the tempo of it and the relentless nature of the drums and then the sub‑bass kind of blowing your head off constantly. The perfect example to me is like the Adele ‘Hometown Glory’ mix, where the original song is just piano and vocal, and then a little bit of strings come in. You’ve got this very kind of gentle, basically acoustic track. But it just so happened to be around drum & bass tempo, so it was a natural fit for me to put some slamming drums and bass over the top of it. I love the contrast of the the softness of the musicality and then the hardness of the drum & bass part.”