William Basinski’s archival recording project gained a life of its own when the tapes began to deteriorate, and then took on a new significance in the wake of the September 11th attacks.

Photo: Sean StoutOne of the most celebrated tracks in ambient music, William Basinski’s ‘dlp 1.1’, the epic, slow‑moving opener of his four‑volume 2002–3 album series, The Disintegration Loops, is a 63‑minute‑long recording of a 12‑inch piece of tape sonically degrading in real time.

Photo: Sean StoutOne of the most celebrated tracks in ambient music, William Basinski’s ‘dlp 1.1’, the epic, slow‑moving opener of his four‑volume 2002–3 album series, The Disintegration Loops, is a 63‑minute‑long recording of a 12‑inch piece of tape sonically degrading in real time.

Back in July 2001, when it was created, ‘dlp 1.1’ was in fact the result of an accident. That summer, Basinski was in his Brooklyn loft attempting to digitise some of his old quarter‑inch tape loops he’d made in the ’80s when he noticed the deteriorating effect and kept his CD burner running. The recording later took on a greater resonance when it soundtracked Basinski’s single‑take video footage, shot from his roof, of the Manhattan skyline in the wake of the September 11th attack on the World Trade Center.

The combination of the visual and sonic elements — smoke billowing across the damaged city, as slowed brass notes from a random snippet of radio‑broadcast muzak gradually decayed — became an unexpectedly powerful one. What had started life as an artful experiment became a poignant audio‑visual tribute to 9/11.

“Yeah, this is where it was like, ‘Oh God, the music has changed’,” Basinski tells SOS today of the moment he realised that he’d created a monument to a tragedy. “The whole world had changed. It was like, ‘This is... well, it’s an elegy now.’”

In its video installation form, ‘dlp 1.1’ is now a permanent exhibit at the National September 11 Memorial & Museum opened in 2014 on the original site of the World Trade Center. Basinski admits that he hasn’t visited the museum, believing he would find the experience too emotionally overwhelming.

“I’m never gonna go see that,” he stresses. “I can’t deal with that.”

Nonetheless, it’s further proof that ‘dlp 1.1’ has only grown in stature in the two‑and‑a‑half decades since its creation. Now Basinski has overseen a new, four‑vinyl box‑set remaster of The Disintegration Loops that reveals all of its strange and fascinating details anew.

“Well, y’know, people discover it when they’re ready for it,” Basinski says of the enduring appeal of The Disintegration Loops, before adding with a laugh, “and then they can’t get enough.”

Beginnings

William Basinski, born in 1958 in Houston, Texas, took a circuitous route into ambient music. His father was a scientist for NASA, working on the lunar module, and so he grew up in Clear Lake City, a planned community populated by many space program workers, including astronauts. When his dad was relocated to Florida, the family went with him.

“I spent a lot of time practising my clarinet because I was quite a sissy,” Basinski says, “and it kept me somewhat out of trouble from the bullies in Florida. Then in ’72 when they cancelled the moon program, we ended up moving to Dallas.

“My parents put us in this very fine school district with a super fun, rigorous music program. In high school I played in the jazz band. I changed from clarinet to tenor saxophone.”

Basinski went on to study saxophone at the University of North Texas in Denton. “I totally screwed my auditions, so I switched to composition,” he says. There, one contemporary music teacher opened up the future avant‑garde composer’s mind. “This was my favourite class,” he remembers, “because he taught us how to listen. He took us out into the fields and made us stretch our ears with deep listening. Then we learned about Cage and all the other possibilities that were available with radio, silence, noise, prepared piano.”

At the same time, Basinski’s fellow students were introducing him to the work of other experimental composers who were to prove inspirational, such as Steve Reich, Terry Riley and Philip Glass. “I got to hear everything that was new and cool and far out. Y’know, Steve Reich’s tape loop studies. And then when Music For 18 Musicians came out [in 1978], where he transitioned that merging and phase‑shifting into the ensemble, that was just so beautiful, I thought.”

It was at university that Basinski first conducted his own tape experiments, ingeniously sellotaping over the erase head of a casette‑recording Sony Walkman so that he could create long, improvised and live‑overdubbed electric piano compositions.

“The first piece was probably around eight to 15 minutes,” he recalls. “We always had a piano in our house growing up, so I could play the piano to compose. I was sort of working on this thing for some time, for some years. I would just, y’know, smoke some weed and fuck around and then try things, and just randomly roll back and intuitively do this other part and see what happened.”

San Francisco

It was through these initial tape experiments that Basinski first met his long‑term partner, visual artist James Elaine. “I was in this very snooty art group of kids the second year after I moved away from the dorm,” Basinski remembers. “Jamie was like the king of this group. He wanted to hear about my music, and so I played it for him, and he said, ‘You’re a genius.’

“So that’s so attractive to hear when you’re 19 years old,” he chuckles. “Very encouraging. So, he fell in love, and I fell in love, and I ended up leaving and moving with him to San Francisco on Halloween, ’78.” The pair ended up living in a six‑roomed apartment on Haight Street where Elaine proceeded to fill every spare room with art installations.

“He would collect these old ’50s TVs off the street and bring them home,” Basinski explains, “and we’d turn them on and see what they would do.” Rather than their visual content, he was more interested in capturing the sounds these decrepit TVs produced. At the same time he’d become a collector of old reel‑to‑reel tape machines.

“So I started just recording everything,” he says. “I got some junk tape decks, these big old Philips or Norelco Continental 40lb portables. You could slow the Norelco way down — seven‑and‑a‑half IPS, three and three‑quarters and then one and seven‑eighths. I just started experimenting with changing speeds and seeing what kind of frequencies I could pull out of these drones I recorded, from the TVs to the refrigerator to everything.

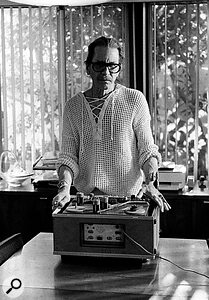

Tape recording and manipulation has fascinated Basinski throughout his long career.Photo: James Elaine

Tape recording and manipulation has fascinated Basinski throughout his long career.Photo: James Elaine

“The sounds in San Francisco were just such a rich ambient environment with the clickety electric buses and then the cable cars creaking, and then you’d have the fog horns. Just really, really rich.”

Another highly influential album for Basinski was Brian Eno’s proto‑ambient classic Music For Airports, released in 1978. “It was sort of like... the melancholy, the delicateness of it, so beautiful. And I was like, ‘Wow, this is amazing.’ And then hearing Fripp and Eno, and then hearing all this drone...

You are reading one of the locked Subscribers-only articles from our latest 5 issues.

You've read 30% of this article for FREE, so to continue reading...

- ✅ Log in - if you have a Digital Subscription you bought from SoundOnSound.com

- ⬇️ Buy & Download this Single Article in PDF format £0.83 GBP$1.49 USD

For less than the price of a coffee, buy now and immediately download to your computer, tablet or mobile. - ⬇️ ⬇️ ⬇️ Buy & Download the FULL ISSUE PDF

Our 'full SOS magazine' for smartphone/tablet/computer. More info... - 📲 Buy a DIGITAL subscription (or 📖 📲 Print + Digital sub)

Instantly unlock ALL Premium web articles! We often release online-only content.

Visit our ShopStore.