Working from a small studio in Quebec, Canada, Pierre Marchand has been responsible for some stunning production work, most notably with songsmith Sarah McLachlan. Paul Tingen finds out how he successfully mixes a technological approach with live performances to create his organic, intimate sound.

<!‑‑image‑>'The only rule is, there are no rules' is probably the most common adage heard in recording studios. It's a phrase that comes up time and time again in interviews, and it's always ironic when interviewees then proceed to describe working methods, approaches and opinions that sound very much like rules. Oft‑heard 'non‑rules' are, for example, that the best songs are written and arranged from the melody downwards, and that it's best to separate out the roles of the producer, the engineer and the mix engineer. And then there's what increasingly seems like the first commandment of modern recording technology: it is very easy to lose sight of your vision, so make your decisions early, record with effects and don't leave yourself with too many possibilities. From this perspective, the 'fix it in the mix' approach is now regarded as a cardinal sin.

<!‑‑image‑>How refreshing then, and how illustrative of the 'there are no rules' adage, that there is a producer out there who flaunts these 'non‑rules' big time, and has in the process managed to make some of the best records of the '90s. Admittedly, he calls his approach "disorganised" and "chaotic," but his results sound the exact opposite. His name is Pierre Marchand, best known for his hand in the creation of five albums by Canadian songstress Sarah McLachlan: Solace (1991), Fumbling Towards Ecstasy (1993), The Freedom Sessions (1994), Rarities, B‑sides, & Other Stuff (1996), and Surfacing (1997), but not her most recent live album, Mirrorball (1999).

Over the past few years these albums have enjoyed a high media profile and been rewarded with impressive worldwide sales. Sarah's two major breakthrough albums, Surfacing and Fumbling Towards Ecstasy, have both gone triple platinum in the USA and Canada, and she enjoyed an impressive hit single in the UK with the graceful ballad 'Adia' (from Surfacing). It's also been raining industry awards, some of which Sarah has shared with Marchand as co‑writer on certain tracks.

Given all the attention McLachlan and her music are getting, it's a bit surprising that the man who has been instrumental in helping her to create her recordings has remained virtually anonymous in the background. Pierre Marchand doesn't only play or program many of the instruments on her studio albums (including bass, keyboards and drum machines); he also records, mixes, and produces all her material. Moreover, he's been doing this since they first met in 1991.<!‑‑image‑>

Swimming & Sailing

Almost all of McLachlan's material is recorded at Marchand's studio, Wild Sky, which is located in beautiful, forest‑covered hills an hour's drive from Montreal, Quebec. But getting hold of him there is not easy these days; Marchand recently spent some of his royalties on a 14‑metre sailing boat, and has been off sailing. He explains: "It gets very cold up here in Quebec, and after eight years here I'd had enough of freezing. I got dreams of world travel, and of pursuing my interests in visual arts. I found a boat in California, and installed a small studio and a dark room in it. The idea was to be more creative, but being on a ship is just not conducive to writing. It's too easy to just... swim!"

In the meantime, Marchand handed Wild Sky Studios over to brothers Dominique and Silvain Grand, who keep the studio running as a commercial facility. I was therefore lucky to catch Marchand on the phone at Wild Sky in late 1999, not only because he's not often there these days, but also because he doesn't normally do interviews. Fortunately, he was happy to make an exception for Sound On Sound...

<!‑‑image‑>Born in Montreal 41 years ago, Marchand has French as a first language, but he told his musical history in accent‑free American English. "I started playing the piano at age 12. By age 15 I had a big rack of synths, and I got going early with music on computers, too: in the '80s I had a PC with Voyetra Sequencer Plus software. Playing with my racks and sequencer was all I did with my days. I played in a rock band for three years, but didn't like it very much.I discovered that I got much more of a kick in the studio, sculpting away at a piece of music for hours on end. I don't get a rush from the presence of an audience; I guess I am a bit of a hermit. So during my twenties I did a lot of theatre and film music.

"When I was 30, I showed my music to Daniel Lanois [legendary producer of U2, Peter Gabriel, Bob Dylan and Robbie Robertson] who suggested that I play it to a record company. They liked it, and I got my first production work through them, in 1988."

Nevertheless, Marchand was not immediately swamped with phone calls requesting his production talents, so he continued doing theatre and film music. Then came another lucky break. In 1991 Sarah McLachlan was looking for a producer to help her with her second album, and Marchand was one of several producers her record company approached. Sarah McLachlan was apparently impressed that Marchand had sent her a tape containing some of his own compositions, and a fruitful creative partnership was born.

Shivers

Marchand's influence was immediately apparent; McLachlan moved on from her rather immature gothic first album Touch and evolved a more modern, technology‑influenced folk‑rock style which began to find form on her second album Solace. According to Marchand, they found common ground in their mutual admiration of Peter Gabriel, but their collaboration went much further than that. McLachlan's third album, Fumbling Towards Ecstasy, followed two years later and is widely regarded as her magnum opus. A marvellous mixture of drum machines and synths with all manner of acoustic instruments, it still stands as one of the classic albums of the '90s. Her most recent offering, the Grammy‑winning Surfacing, is a starker, purer, more acoustic album, with a powerful melancholy streak.

Marchand explains some of the thinking that went into these last two albums: "I have definitely been influenced by trip‑hop folks like Massive Attack, Portishead, and Tricky; that has found its way into my work. The drum machines and synths and dance music influences are really me having fun with the technology. Sarah doesn't really like drum machines. I used the sounds of a Roland TR808 on a few tracks on Fumbling..., like the title track and 'Mary', and Sarah told me afterwards: 'I don't like the 808.' She certainly does not keep her opinions away from me, so she must have realised this after the record was done. But I do think Fumbling Towards Ecstasy was our best album. I was determined to make the best record ever, and I think the track 'Fear' was my highest achievement. The end result still sends shivers up my spine.

"On Fumbling we were always trying to go in non‑obvious directions, like with the song 'Hold On', which was a very slow, jazzy, dark, quiet song. I tried to offset that with a rocking rhythm on the drum machine, which took it in a completely different direction." This unconventional approach was maintained on some tracks on the Surfacing album, as Marchand goes on to explain: "The track 'I Love You', was a romantic song with violins, but to keep it away from a Hollywood sound, we decided there was no need for the big drums and the three‑second reverb on a heavy snare that you'll get in big ballads. Instead I added drum machine to the string arrangement, and created a hypnotic sub‑bass feel using a sine wave from an Emu E4 sampler."

On the whole, however, Marchand acknowledges that the recent album was more straightforward. "The approach to Surfacing was a reaction to the previous album. We all thought we could never do another Fumbling, and I thought we should make a simpler, less ethereal record. I think we achieved this. There was a conscious decision to just go with the songs, and simply make them what they were."

In short, Fumbling... is complex and technology‑orientated, with a central place for the drum machine, whereas Surfacing is more acoustic, organic and straightforward. In one song, ('Angel') the stripped‑down arrangement consists of just an acoustic piano and acoustic bass, and on many of the tracks the only players are McLachlan, drummer Ash Sood, and Marchand.

Now I find that when the band or individual musicians come in, saying nothing is the best thing; I allow myself to be surprised by what they do. I simply put the mics up, press Record, and if they're good musicians they'll come up with something interesting.

Wilder Skies

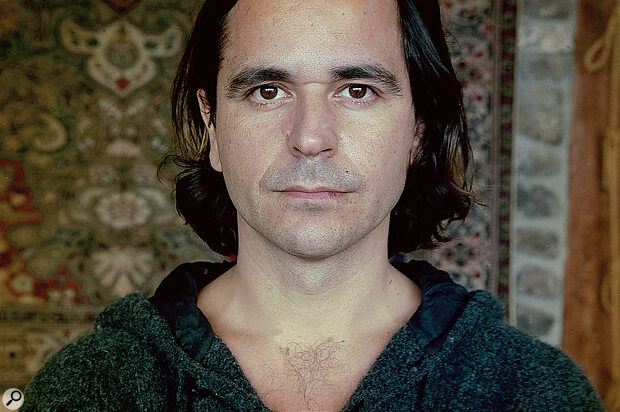

Pierre Marchand at his atmospheric Wild Sky Studios, Quebec, Canada.

Pierre Marchand at his atmospheric Wild Sky Studios, Quebec, Canada.

Marchand explained how the pair's musical collaboration started and how this led to the founding of Wild Sky Studios. "The first album we did, Solace, was recorded on a 3M 24‑track, in various places, including Vancouver and Daniel Lanois's place in New Orleans. During the pre‑production for that album we were looking for some quiet space to work, and stumbled on this house here by chance. We rented it for a month or two, and everything we did sounded great, so after a year of going from studio to studio I came back andrented this place permanently. It's a beautiful house near a cliff on a hundred acres of woodland. It's a good place to get away from it all, and very pretty in winter... just really cold! It's owned by a painter, and I set the studio up in the painter's studio, which is an area with a lot of daylight. It also is a great‑sounding room."

The atmospheric room can be seen in some detail, lit by candles, on the interview video that's part of the QuickTime multimedia section of the Surfacing Enhanced CD. According to Marchand, the candles aren't quite as abundant in real life, but the room definitely has a very homely ambience. Contributing to this feeling is the 32‑channel Helios mixing desk, which is placed right in the recording area rather than in an acoustically isolated control room. "I've never liked working in traditional studios; I prefer to be in the same room as the artist all the time. I never use iso‑booths or recording‑only areas; everything is recorded around the console.

"The reason is that I don't like talkback. I go for performance, and communication is better like this. In any case, I always record everything flat, so there's no need to twiddle knobs during recording. I put up a mic and if it sounds good, wonderful, if not I move it or try another. But I don't spend a lot of time trying out or putting up microphones. Most microphones here are set up permanently, and that works fine. I may change or EQ the sound during the mixing stage. Sonic perfection is not my primary aim, which is why I prefer to engineer things myself. I figure that if there are four technical people in a room, such as engineers and assistant engineers, the whole atmosphere gets so technical that it creates a laboratory mood. I'd rather have only people present who are making music, and capture that with the gear."

Writing & Technology

All the albums that Marchand recorded with Sarah McLachlan after Solace were recorded at Wild Sky, following a similar approach. They always begin with a lengthy pre‑production process, with just Marchand and McLachlan sitting together at Wild Sky and mapping out the songs. Marchand elaborated: "We figure things out between the two of us. We get a mood and a direction for the songs, and the musicians we get in later tap into that. Usually we develop ideas that Sarah brings in; sometimes we write songs together. 'Building A Mystery', for example [from Surfacing], was a combination of some chords that Sarah played that fitted with a chorus melody line and some words that I had written. For Fumbling Towards Ecstasy we enjoyed the first week of pre‑production so much that we thought we could just stop there and put out a record. You can hear some of that stuff on The Freedom Sessions album, which was released two years after Fumbling. Some of the tracks on it are the results of that first week of experimentation. The rest is a live band improvising completely new versions of older songs.

That's another thing I love about the RADAR; the fact that there's an Undo mode. This means that when I cut and paste, I can be deliberately careless. I'm always hoping that a mistake will turn out brilliant.

"Once Sarah and I have the structure for the song, my sampling drum machine and sequencer, the Akai MPC60, is my starting point for the arrangements. I've used the MPC60 for all the albums. The TR808 on Fumbling was sampled into the MPC60, because you can do many more things with the sounds in the MPC60. Also, I find it easier to create original drum rhythms that way. Drummers have their set of drumbeats, and to play the kick drum in an unusual place may be unnatural for them. Ash Sood [Sarah's drummer and husband] is really open to creating unusual things. He doesn't mind stealing from what I come up with on the drum machine, or me editing the things he does in my Otari RADAR. He may improvise for four minutes, and I may find one fragment of that, loop it and use it as the basis for a song.

<!‑‑image‑>"On Fumbling I also hired a local drummer who is legendary in Montreal, called Guy Nadon. He's very eccentric and funny, and a fast player. I asked him to play some rhythms, but it sounded too much like a jazz big band, and I was afraid I could not loop any of his playing for Sarah's songs. So I got a whole bunch of CDs, randomly choose one from the pile, gave Guy a five‑second taste of a rhythm, and asked him to do something similar. He would ask me to hear more, but I refused, because my idea was that he wouldn't play exactly like the example, but just a similar tempo, feel, and beat. I created three different loops in the Emu E4 from three dozen different beats, and one was used on the track 'Ice Cream' [from Fumbling Towards Ecstasy].

"During the pre‑production period we do a lot of experimentation with rhythms, with textures, and especially with the vocals. I will sometimes record as many as 20 tracks of backup vocals. The advantage of working here in Wild Sky is that I can record her well from the start. Most of those early vocals are retained. We still try to get better vocals later on, but it seems that when there's little on tape, the vocal is more focused. If you record a vocal to a finished backing track it often doesn't work. Moreover, this way of working means that everybody in the band plays to the vocal, which helps to keep them focused."

<!‑‑image‑>It might initially seem strange that it is when discussing his use of live musicians that Marchand really starts to wax lyrical about the advances in recording technology, particularly his Otari RADAR system. But it becomes clear he favours the use of live players in tandem with the editing freedom the digital recorder offers. "When I started producing, I would tell a band exactly what to play; I was like a dictator. But this was in the days of analogue, when it was much harder to play around with the performances after they were done. I did manage to do edits with analogue multitracks as well, using two multitracks and a 4‑track Akai D4, using slave reels and flying things in. But often, it was a nightmare."

By the time Marchand and McLachlan recorded Surfacing, the recording was all done on a RADAR. "I can't live without that machine. I got one early; I wanted to be a guinea pig, because of all the editing you can do with it. Flying things around, creating loops, offsetting the timing. It's practical and great fun.

"Now I find that when the band or individual musicians come in, saying nothing is the best thing; I allow myself to be surprised by what they do. I simply put the mics up, press Record, and if they're good musicians they'll come up with something interesting. I tell them that it doesn't matter if they make mistakes; I just want them to get comfortable, play and enjoy themselves. If you look at the floor of the studio here, you see that it's not about playing things right. It's a very cosy and fun place to work, with a floor full of paint and wires; it's very messy and that's what I now like in music. I like them to do whatever they want, and I can figure out what to do with it later, because I can fix it in the RADAR. If a drum fill doesn't work, I can just take it out, or put it somewhere else. The technology has opened up new creative possibilities."

Another example of this can be found on the track 'Sweet Surrender', from the Surfacing album. The rhythmic sound at the beginning, which resembles a hooting car, is actually bassist Brian Minato going haywire with feedback on an electric guitar. Marchand: "I asked him to put the amp at 11 and just go for it. He learnt the chords as he went along, and he filled the track up with feedback. Later I went through it in the RADAR, found bits of feedback that fitted with the chords, and put them in places that worked. I then created a rhythm using the mutes on the Helios, and to get this idea perfectly in rhythm I programmed the sequencer, and keyed a noise gate with it."

Examples like this prove that Marchand revels in the freedom that hard disk editing allows him; he now has the same control over 'real' audio as MIDI sequencing once gave him over synths and samplers. On the MIDI front, he's unusual in having used PC‑based sequencers since the '80s. On Surfacing he used the MPC60 purely for drum loops, whereas keyboards and samplers (a Kurzweil K2000 and Emu E4) were sequenced in Emagic Logic Audio for the PC, using an Aardvark 20/20 soundcard. Having seen his K2000 and Emu E4 unable to cope with life on a sailing ship, he's now also using PCs in his studio on his boat, with Sonic Foundry's Sound Forge for editing and mastering, and Nemesys's Gigasampler software‑based sampler. "That's convenient because it takes one second to load a bunch of sounds instead of 30, and you can have a piano sound that uses 1Gb of memory, with every note fully sampled. I have an MPC2000 and a Ensoniq PARIS system on the boat as well."

<!‑‑image‑>However, recently Marchand has decided to switch over to a system based around MOTU's Digital Performer on a Mac (already in use at Wild Sky under Dominique and Sylvain Grand), for reasons of user‑friendliness and stability. He explains that in this whole area, convenience is what matters to him most. "The song and production are more important than a great sound. I don't have a problem with digital sound or digital editing. The musical possibilities it opens up far outweigh any sonic shortcomings digital may have."

Mr Fixit

More views of the impressive Wild Sky. Everything is arranged within one room, even the Helios desk, to facilitate better communication while recording.

More views of the impressive Wild Sky. Everything is arranged within one room, even the Helios desk, to facilitate better communication while recording.

Once again operating against all the prevailing wisdom, Pierre Marchand loves to 'fix things in the mix'. The studio sinner: "I spend four days per song mixing, because that is when I take most of the decisions. There'll be a lot of EQ‑ing going on, and I'll add effects and edit. There might be additional overdubbing, and the song structure might still change at this stage. A song might be six minutes long, with all sorts of ideas on tape. During the mix I'll narrow things down, select all the best moments, and the song may get shorter and more condensed. If you work on a song for four days, you tend to lose some stuff."

Not everyone would agree with that last statement; some bands seem to have a tendency to fill more and more tracks the longer they work on a piece of music. Marchand agrees that this is a danger, and that it's not easy to remain objective with this working method. Nevertheless, it seems to suit him: "I actually really like doing things like finding the good 30 seconds of music in 15 takes, selecting the best bits and comping them together. And of course I have a safeguard in Sarah. When I start a mix I'll simply put up the faders, and try to make everything fit. Once it starts sounding like a song, I start looking at making musical changes, like edits or overdubs. Sarah is fully involved at this stage, but she will let me work alone for long periods of time, and when I've achieved something, she'll come in with fresh ears to make decisions."

Marchand records most sounds dry, only occasionally printing effects on a separate track to help create a mood for a song during recording. But at the mixing stage, these effects are usually erased, and he'll start to create a coherent soundscape from scratch. Favourite effects include those from the Eventide H3000, Lexicon PCM90 and PCM80 reverbs, delays, echo, flanging, and tremolo, which he creates in the simplest way imaginable: "If you hear tremolo on any CD I have produced, it's actually board automation and a fast wrist!" But his favourite tool is again the RADAR, which he often wheels out for extensive edits at the mix, such as on the track 'Building A Mystery' from Surfacing: "The solo on that was created in the RADAR. I borrowed chords from the song and placed them in a different order, and Sarah's guitar solo, as well as her 'oooohs,' go into a multitude of reverse and forward modes. A few hours passed before I was happy with that break, and there were quite a few lucky mistakes involved. That's another thing I love about the RADAR; the fact that there's an Undo mode. This means that when I cut and paste, I can be deliberately careless. I'm always hoping that a mistake will turn out brilliant."

So this is Pierre Marchand: highly creative and innovative, breaking all the rules, and truly using the studio as a musical instrument. From this perspective it is to be hoped that he will soon get bored with sailing and swimming, and return to production and the recording studio. As it happens, Sarah McLachlan has just gone into semi‑retirement, planning to start a family. But Marchand is insistent: "I'm sure I'll do more music, I'm thinking about a project for this Spring at this moment. And hopefully Sarah and I will work together again, aiming for a masterpiece better than Fumbling."

One thing is for certain; there won't be any recording rules standing in his way.

Wild Sky Studios Selected Gear List

| RECORDING • Apogee PSX100 A‑D converters.

OUTBOARD

• Aphex Expressor compresssor.

multi‑effects.

multi‑effects. | • Lexicon PCM90 reverb.

Preamp (x2).

compressor (x2).

MICROPHONES • AKG 414 (x2).

| • Neumann M147 (x2).

INSTRUMENTS

grand piano.

|

The Inexact Science — Miking With Marchand

Marchand claims that he's "not big on sound," and clearly the whole audio engineering side of recording is not his primary focus. He fondly relates an anecdote: "I once asked Daniel Lanois for advice on how to get a good acoustic guitar sound. "His answer was 'first get a good‑sounding acoustic guitar'. I suppose that's a rule that goes for almost everything you record." And Marchand's recorded work bears this out — he obtains a beautiful piano sound, for example, simply by placing two Neumann KM150 microphones right above the instrument's strings. Mind you, the piano in question is a 19th‑century Steinway Model B Grand...

Nevertheless, top American mix engineer Tom Lord‑Alge, who remixed some of McLachlan's songs for single and radio versions, has recently commented that Marchand's recordings, especially the vocals, are always recorded to a high standard. Marchand, though, explains that away with reference to his highly regarded Neve 1073 mic preamps, which he has been using for over a decade, and mic technique, although in his case this is hardly a precise science. "I think microphones are a matter of experience and listening carefully. I get mics that I'm told are good, try them all out on an instrument, and choose the one that sounds best. I spend the next three minutes with the headphones turned up loud, moving the mic around the instrument until it sounds right, and leave it there. Next I get a decent recording level — and that's where I stop. I don't add EQ or compression or effects, apart from some compression when recording vocals, because they're too dynamic.

"In Sarah's case, I recorded her with a Neumann U47 until Surfacing, and then switched to Neumann 149, which has a sweeter top end. I don't have to EQ it later at the mix. I compress her voice a little with a Tubetech CL1 — just minimum compression, with a fast attack and medium release. I have also noticed that, as time passed, I started moving the microphones further and further away from the source, because I found that the more room sound I got, the more interesting or natural the results were. When I first started with acoustic instruments I made the mistake of recording everything with the microphones right up close, and I then had to do a lot of fixing at the mix. Sometimes, though, close‑miking can sound excellent, and I still end up with microphones in the strangest places."