Celebrated producer and engineer Roger Nichols begins his new monthly column in Sound On Sound with the fruits of bitter experience archiving digital audio.

Roger Nichols has been professionally involved in the music business since 1968, working as a staff recording/mixing engineer at ABC Records and Warner Bros before becoming an independent engineer/producer in 1978. His work with Steely Dan in particular has led to a string of Grammy Awards and nominations, including a Best Engineered Album award for Two Against Nature. An advocate of digital recording since 1977, Roger designed and built the first digital audio percussion replacement device and has lectured on digital audio around the world.Photo: Ashlee Nichols

Roger Nichols has been professionally involved in the music business since 1968, working as a staff recording/mixing engineer at ABC Records and Warner Bros before becoming an independent engineer/producer in 1978. His work with Steely Dan in particular has led to a string of Grammy Awards and nominations, including a Best Engineered Album award for Two Against Nature. An advocate of digital recording since 1977, Roger designed and built the first digital audio percussion replacement device and has lectured on digital audio around the world.Photo: Ashlee Nichols

I am proud to be a part of the Sound On Sound team. I have always admired the magazine for its integrity and 'bleeding edge' coverage of all things audible.

I am a hi-tech kind of guy. I love technology. If it does not contain highly sophisticated technology that is in beta-test stage and crashes weekly because I am pushing it to the edge, then I don't want it. Whether it is the latest digital audio workstation, or a toaster that uses video technology to detect the perfect shade of golden brown before ejecting, then emails me when the toast is ready, I must have it. I always install the most current version of everything. If the firmware revision in my electric shaver is not the most recent, I will demand an update or replacement before someone catches me with outdated devices in my possession.

This does come back to bite me sometimes, like when I upgraded to Mac OS X 10.4, which made my Pro Tools quit operating. It was a month before the Pro Tools update was available. I waited. No way in hell was I going to reinstall a previous version of OS X. It is a gene-pool thing.

I keep a database of seemingly unimportant dribble about how things work and small details about things that don't matter, and weeks or years later, these can help to solve a problem. One example is Sony's design of the portable DAT machine. Small differences in the design to save money during manufacturing turn out to be important when trying to recover old DAT tapes that won't play back.

DAT Tape Archiving

I have lots of DAT tapes that I am moving over to CD while they are still recoverable. Well, while most of them are recoverable.

DAT tapes are recorded like video tapes, using a helical scan process where a high-speed spinning drum records tracks at an angle across slowly moving magnetic tape. On playback, the spinning heads must track this previously recorded information without errors for your data to be recovered successfully.

The track on video tape records analogue signals in a continuous track as the head sweeps its arc across the tape. DAT records digital data (as analogue frequencies that represent digital information) in multiple small packets during each pass. Each packet contains the address of where its data belongs in the data stream. The packets contain error-correction information and are interleaved out of order to make the data stream more robust.

DAT tape is recorded on Mylar tape, which deforms slightly over time. After 10 or 15 years, the track of information on the tape is no longer straight. Because the track is as narrow as a human hair, any deformation makes the playback head miss some packets of information. If too much information is missed, then the error correction is ineffective, and the data stream is muted. Audio dropouts occur.

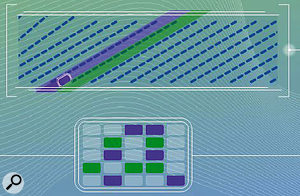

The record head in a DAT machine — and in Exabyte's new DAT-based backup system — is angled across the tape (top), recording 'packets' of data in diagonal stripes. Each packet contains information about its own position in the data stream, so the data can be recovered even if it is read out of order (below).Photo: Ashlee NicholsI accidentally discovered a way to play back these problem DAT tapes when I was reading a Sony technical manual about the specifications of DAT in all of its incarnations. (Hey, I was flying on a Sony corporate jet and it was in the seat pocket!)

The record head in a DAT machine — and in Exabyte's new DAT-based backup system — is angled across the tape (top), recording 'packets' of data in diagonal stripes. Each packet contains information about its own position in the data stream, so the data can be recovered even if it is read out of order (below).Photo: Ashlee NicholsI accidentally discovered a way to play back these problem DAT tapes when I was reading a Sony technical manual about the specifications of DAT in all of its incarnations. (Hey, I was flying on a Sony corporate jet and it was in the seat pocket!)

It turns out that portable DAT recorders work differently from full-size DAT machines. The full-size DAT machine has a large-diameter head drum and incorporates two servo systems for playback. One servo controls the linear speed of the tape and the other servo controls the rotational speed of the head drum (in sync with the linear speed of the tape). The portable DAT uses only one servo to control the linear speed of the tape. The head drum is smaller and spins at twice the speed of the larger head drum. There is no synchronisation between the linear speed of the tape and the rotational speed of the head drum.

Remember I mentioned that the data on a DAT tape is recorded as blocks of information. Each block has an address so that when read it can be put back in the proper order. The fast-spinning head drum blindly reads every block it goes over. Each time it goes over a block it reads it, checks the address, and if there are no errors it stores the data in the proper sequence for playback. With this playback method, each block is read an average of 2.5 times and it does not matter if the track is straight or deformed.

So far, my portable DAT has successfully read every DAT tape that has failed to play back in a full-size DAT deck. I have been able to transfer every DAT tape I ever recorded to audio CDs for listening and DVD-R for archiving.

Tune in 15 years from now and I will talk about the transfers from DVD-R to whatever the flavour of the month happens to be then...

Should DAWs Go 'Beep... Beep...' When You're Backing Up?

I don't have an answer to this question, and I don't have the answer to the backup problem, but I have been trying to get a grip on it for 25 years.

Backing up data has been a dilemma since Moses came down the mountain with the 15 Commandments. According to Mel Brooks's History Of The World — Part II Moses dropped and broke the third tablet that contained the additional five Commandments. There was no backup. We will never know for sure what was on that tablet, but I suspect it had something to do with backing up your data to more than one format, and making sure your tracks in a Pro Tools or other DAW session are not named 'Audio-1, Audio-2, Audio-3', and so on.

I am an expert at backing up to the wrong format, however. I used to back up to extra hard drives. I would install a second drive, format it, and copy everything that would fit onto it, remove it and store it on a shelf. As drives got bigger I always backed up to the biggest, baddest Firewire, USB, Fibre Channel, SCSI or whatever drive was available. Nobody ever told me that you were supposed to 'exercise' each drive once every two or three months by reading the data or you would lose everything. This was not mentioned until some record company needed to get a session off of a hard disk that had been sitting in the archives for 10 years — and it was empty, or the drive would not spin up because the bearing grease was solid as a rock.

I immediately grabbed all of my stored hard drives and started finding computers to connect them to so I could see if my precious data was still there. Ten percent of the external Firewire drives would not spin up. During one Steely Dan tour, we recorded all of the shows using a pair of Mackie 24-track hard disk recorders. We filled 70 20GB drives. None of them will spin up now.

Back To DAT

Except for the Steely Dan shows, I have always backed up to multiple formats. When hard disks were small, I also saved to an Exabyte 8505 tape drive. When CD-R became available I backed up to CD-R. I now use DVD-R as well as Firewire with 500GB drives. It takes over 100 DVD-R discs to duplicate a 500GB drive, so I make sure I save projects as I go to ease the burden.

Exabyte have a new tape backup drive, the VXA320 160GB/320GB (native/compressed) single tape unit and the VXA320 Packetloader 10-tape auto-changer. The drive mechanism uses the same technology as the DAT tape. Data is recorded in addressable blocks. During playback the head spins at a higher speed to recover the blocks. They have wrinkled the tape and dropped it in hot coffee, but the data was still recovered 100 percent.

My VXA will be here next week and I can start re-backing up my backups. Beep... Beep... Beep.

Roger Nichols can be contacted at SOS@rndigital.com.