Our four-part series charts the most important technical breakthroughs in music history.

A lot has happened since the first issue of Sound On Sound appeared in October 1985. Music technology and the music industry have changed beyond all recognition. Today’s home computers can do things that would have seemed impossible in the mid-’80s. But how did we get here? To mark Sound On Sound’s 40th anniversary, we have put together a list of 40 milestone developments from the history of recording and production, which we’ll be counting down over the next four issues. Agree? Disagree? What have we missed? Get in touch on feedback@soundonsound.com to share your own thoughts.

40: Spectral editing

Spectral editing is a digital-audio processing technique that allows users to view and manipulate sound using a spectrogram display that simultaneously shows time, frequency and amplitude, rather than just a waveform. First seen in CEDAR Audio’s Retouch process, launched in 2002, the display makes it possible to visually identify and isolate different sounds that occur simultaneously, thereby facilitating the removal of clicks, hums and other background noises often without affecting the surrounding audio. Retouch, along with Steinberg’s SpectraLayers (originally developed by Divide Frame and published by Sony) and iZotope’s RX software, has a signal-focused approach optimised for use in post-production and restoration, whereas a more music-based app like RipX uses a slightly different spectral analysis that is more note‑ and harmonics-based, with a focus on instrument separation. Melodyne, similarly, uses a form of spectral note extraction alongside polyphonic pitch detection to create its unique visual editing interface.

39: Drum sample replacement

Producer Roger Nichols developed the first drum sample replacement system.Steely Dan producer Roger Nichols bought his first computer in 1976. By 1978 he had developed the first version of Wendel, a drum machine that employed 12-bit, 125kHz sampling. It wasn’t the first digital drum machine but, uniquely, it had an envelope follower that allowed it to be triggered from a pre-recorded drum track. Existing kick and snare sounds could be replaced with factory samples, or you could sample and replay clean hits from your own multitrack. Wendel was first used in January 1979 on Steely Dan’s album Gaucho, and was superseded by the 16-bit MkII version in 1981.

Producer Roger Nichols developed the first drum sample replacement system.Steely Dan producer Roger Nichols bought his first computer in 1976. By 1978 he had developed the first version of Wendel, a drum machine that employed 12-bit, 125kHz sampling. It wasn’t the first digital drum machine but, uniquely, it had an envelope follower that allowed it to be triggered from a pre-recorded drum track. Existing kick and snare sounds could be replaced with factory samples, or you could sample and replay clean hits from your own multitrack. Wendel was first used in January 1979 on Steely Dan’s album Gaucho, and was superseded by the 16-bit MkII version in 1981.

38: Parallel compression

Unlike standard compression, which reduces peak levels with the aim of controlling overall dynamic range, parallel compression blends a heavily compressed version of an audio signal with the original unprocessed signal. This has the effect of maintaining all the transients and dynamics of the peaks whilst still adding density through raising the level of quieter parts of the source via the compressed path. The most common setup is to route a track to a secondary channel or auxiliary bus, where heavy compression is applied, before mixing that signal alongside the dry track. The audible effect is denser and more powerful, just like normal compression with some make-up gain applied, but without any loss of transient detail — a common side-effect of compression — because the dry, uncompressed track is always louder on the peaks. It’s commonly used on drums, sometimes vocals, and even full mixes to increase average loudness and perceived energy. The technique is sometimes referred to as ‘New York compression’ because of its frequent use on New York disco and pop recordings in the 1970s and 1980s.

37: Re-amping

Re-amping, as used in the context of guitar recording, refers to recording a clean, direct signal via a DI box that can subsequently be replayed through a guitar amp and re-recorded. The player will usually be listening to a guitar amp at the time to help with the original performance, but the technique allows the sound to be altered or improved later without requiring the part to be played again. When re-amping it is important for the playback signal to match both the level and source impedance of a typical guitar signal to ensure that the amplifier will react normally in terms of distortion and tonality. A number of dedicated impedance-matching boxes are now available, notably Radial’s X-Amp. Re-amping is often cited as being ‘invented’ in the early ’90s, but was actually in regular use well before, using either custom‑made adaptors, or even passive DI boxes connected backwards, so the amp would see the high-impedance side of the box.

36: Noise reduction

Dolby Laboratories developed their A-type process in 1965 to combat the high-frequency hiss inherent in analogue tape recording. In the following years, as multitrack tape recorders added more discrete tracks to the standard tape widths, the Dolby process became an essential component of many professional multitrack recording studios. The rival dbx system, using a full-bandwidth compander to compress the signal during recording and expand it on replay, was effective at suppressing noise, but could also produce audible noise modulation. The Dolby system avoided this by dividing the audio spectrum into four separate frequency ranges, applying compression and complementary expansion separately in each band, reducing noise by up to 10dB in the midrange and 15dB at high frequencies without significant side-effects. Dolby-based systems always had to be carefully calibrated to ensure that the record and replay levels matched, otherwise the encoded signal would not be properly ‘decoded’. By the late 1980s, higher fluxivity tape formulations and 30-ips working were often preferred to using Dolbys for noise reduction.

35: Mixing in the box

Ricky Martin’s 1998 global chart-topper ‘Livin’ La Vida Loca’ is notable for more than just its singer’s chiselled good looks, or its unusual success in bringing Latin music to a mainstream audience. It’s generally regarded as the first number one single to be mixed entirely in software, without the assistance of a hardware console or any outboard processing. The software in question was, of course, augmented by hardware DSP cards, but even so, ‘Livin’ La Vida Loca’ was a recognisable landmark along the path to the current situation where composers and producers can work anywhere, with only a laptop and a pair of headphones.

Sony’s pioneering real-time convolution reverb.

Sony’s pioneering real-time convolution reverb.

34: Convolution

Convolution exploits the idea that every single sample in a digital recording can be considered, in its own right, an instantaneous impulse with a given amplitude. So if we have another digital recording that actually represents the response of a room or other structure to an impulse, we can impose the sound of that room on the first recording by playing back the second one over and over again, with its amplitude adjusted to that of each sample in the first. This process was understood many years before it became practical to implement, with the first real-time convolution reverb being Sony’s DRE S777 from 1999. Not all of the claims made for convolution in its early days were fulfilled, because the realism of simple implementations is compromised by its inability to capture time-variant or non‑linear phenomena, but many of these shortcomings have now been addressed. As well as powering many reverb plug-ins, convolution is now also the standard technique behind loudspeaker emulation in amp simulators.

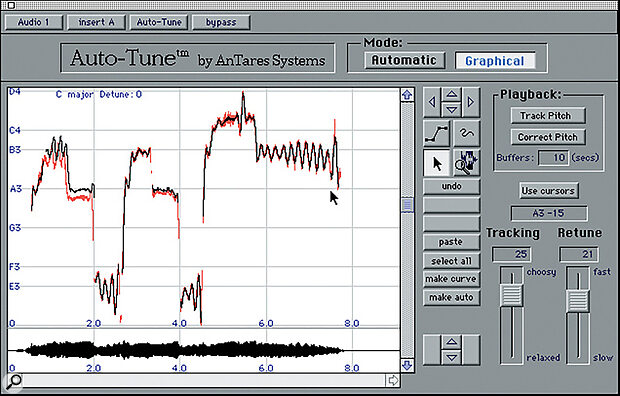

Used with discretion, Auto-Tune could eliminate ‘pitchiness’ from a sung vocal in a remarkably transparent way. But what no-one had anticipated was that producers would use it without discretion.

33: Pitch correction

In 1996, physicist Andy Hildebrand was inspired to apply some of the insights he’d gained in the oil and gas industry, where he worked on improving the interpretation of radar images, to audio. The result was something previously thought impractical: a real-time algorithm that could analyse and automatically correct the pitch of monophonic audio. This algorithm formed the basis of what may be the single most influential plug-in of all time. Used with discretion, Auto‑Tune could eliminate ‘pitchiness’ from a sung vocal in a remarkably transparent way. But what no-one had anticipated was that producers would use it without discretion. Cher’s 1999 mega-hit ‘Believe’ showcased the uncanny sound that could be achieved with fast retune speeds; at the time, it seemed like a novelty, but the effect has become part of the standard sound palette of hip-hop and R&B.

An early iteration of Antares' Auto-Tune plug-in.

An early iteration of Antares' Auto-Tune plug-in.

32: Time-stretching

The ability to play back recorded audio faster or slower without changing its pitch might seem like a quintessentially digital phenomenon. Not so. German inventor Anton M Springer published a paper in 1957 describing his all-analogue, tape-based Acoustical Time Regulator, which he had demonstrated in operation four years earlier. Four playback heads were mounted on a cylinder which could be rotated independently of the tape speed. Switching between the heads allowed short segments of the audio to be repeated or omitted, depending on whether the tempo was to be reduced or increased. Springer claimed that tempo could be varied by ±30 percent with no loss of audio quality.

31: MIDI recording sync’ed to tape

From the perspective of today’s ‘in-the-box’ DAW production techniques, it is easy to overlook the mid‑’80s technology revolution that came before. Early MIDI sequencers, whether in software or hardware, could start in sync with a multitrack tape machine and continue running in parallel using a rudimentary sync code, but they always had to start from the beginning. Clearly, this was of no practical use in an overdub session where you might shuttle about endlessly. Everything changed, however, with the development of the ability to lock sequencers to industry-standard SMPTE timecode. This meant that the sequencer would start playing in sync at whatever point you started the tape, effectively adding ‘virtual tracks’ to any size of multitrack setup. In the era before audio recording on computers, software sequencers such as Steinberg’s Pro 24 and C-Lab’s Notator became perfect companions to the narrow-gauge multitracks of the day, as fundamental elements like drums and bass parts never needed to be recorded to tape at all. It was also possible to edit the MIDI elements of a performance, or indeed change sounds, right up to printing a final mix.

Parts 2, 3 and 4 to follow!