Silver Apples jammed with Jimi Hendrix, counted John Lennon as a fan, and produced extraordinary electronic music — with nothing but a drum kit and a pile of electrical junk.

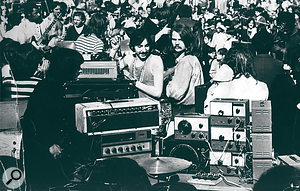

Silver Apples live in Los Angeles, 1968. "In this shot you can see I have the oscillators mounted horizontally in plywood along with echo units, wah pedal, and so on. Here I am playing the 'lead' oscillator with my right hand, keying in rhythm oscillators with my elbow on the telegraph keys, changing the volume on an amp with my left hand, and singing. This was typical.”

Silver Apples live in Los Angeles, 1968. "In this shot you can see I have the oscillators mounted horizontally in plywood along with echo units, wah pedal, and so on. Here I am playing the 'lead' oscillator with my right hand, keying in rhythm oscillators with my elbow on the telegraph keys, changing the volume on an amp with my left hand, and singing. This was typical.”

Having languished in obscurity for many years, '60s US duo Silver Apples are now being widely recognised as pioneers of electronica, thanks to their ground‑breaking work in melding psychedelic rock with primitive oscillators. At the time, certain switched‑on tastemakers such as John Lennon and sometime collaborator Jimi Hendrix sang their praises, but it's been in latter years, with the likes of Beck, the Beastie Boys, Stereolab and Portishead's Geoff Barrow all acknowledging their influence, that the band's renown has grown. Despite having released only two albums during their first flush of creativity, it seems that Silver Apples' electronically enhanced, wigged‑out pop has cast a long shadow. "It's extremely rewarding as an artist that the documents of activity that I did all those years ago are being thought of as references by other musicians,” says the band's singer/electronicist Simeon today. "It just astonishes me that it's taken on this kind of importance.”

The Overland Route

Silver Apples' music was unprecedented in 1967, with Simeon sailing heavily treated oscillator sounds over drummer Danny Taylor's unrelenting beats. Yet the roots of this highly original sound were, ironically, to be found in a mundane New York bar band, featuring Simeon on vocals and Taylor on drums, called the Overland Stage Electric Band. "Very much a club band supporting the lead acts,” Simeon remembers. "The audiences would not really be interested in hearing any original music, it was all covers of the various danceable songs of the day. We played every single night, sometimes two or three sets a night. It was just like going to work.”

All that was to change when Simeon was introduced, by a classical musician friend then beginning to explore leftfield composers such as Stockhausen, to an oscillator that had been built in the '40s. "He'd drink vodka and play the oscillator along with Beethoven. And one time when he was just completely passed out drunk, I put on a record — I forget what it was, whatever rock & roll record he happened to have around — and I started playing along with it with a rock band and I said, 'Oh my God, this works, I like this.' I borrowed it from him and he eventually sold it to me for $10.”

No Imagination

Simeon playing live in Tokyo, 2009, using his right hand to manipulate the trademark oscillators and his left to trigger an Akai sampler.

Simeon playing live in Tokyo, 2009, using his right hand to manipulate the trademark oscillators and his left to trigger an Akai sampler.

Simeon decided to try to introduce an electronic element to the Overland Stage Electric Band. From the first rehearsal, however, it was clear that, Taylor aside, the others didn't share his vision. "They felt it was too over‑the‑top for them. They were traditional, they played a lot of blues riffs, and when I came in there with all these atonal things, they didn't know how to react to it. I don't think they had any imagination, y'know. Or somehow they felt threatened by it. Instead of saying, 'Hey, this is kinda crazy, this is interesting, let's see what we can do with this,' they rejected it.”

And so Simeon and Taylor splintered off and formed Silver Apples. Soon the pair were performing at Greenwich Village's Café Wha? and at free festivals organised by a cultural committee in New York keen to divert the attentions of the city's youth from protesting against the Vietnam war. As a result, most weekends Silver Apples found themselves playing to crowds of around 30,000 in the various city parks.

Having now gathered together a collection of oscillators, Simeon would simply pile them up on a table. "It took me about two hours just to set it up,” he laughs. "So that got us to thinking about how to put it into pieces of plywood and get them all wired together underneath, so that I didn't have to make all those connections. That kind of led to calling it something.”

After their signing to the tiny record label Kapp, Silver Apples' now plywood‑housed collection of oscillators was named by the company bosses The Simeon, in honour of its creator. It's a fact that now makes Simeon himself cringe slightly. "I didn't have anything to do with that,” he says. "That was strictly a publicity thing for the record label.”

Whatever the origins of its name, however, The Simeon was a remarkable, Heath Robinson‑like creation involving 13 oscillators, fed through various Echoplexes and wah‑wah pedals. More impressive still was the way in which Simeon managed to control this strange invention.

"At the same time as I'm moving the dials with my right hand on the lead oscillator,” he recalls, "I'm working my elbow up and down across a bank of telegraph keys so that my forearm is keying in two or three of the other oscillators that have been pre‑tuned to different notes. So that way I'm creating a little rhythm section. At the same time I have some on/off switches underneath and so I'm playing a sort of repeating, rolling bass line with my feet. On top of that, I had to sing. In the meantime, Danny's wheeling away on the drums. That was basically our act. It was almost like a one‑man band with a drummer.”

At one key point in the early Silver Apples set, meanwhile, Simeon would ask the audience to shout out their favourite radio stations' dial frequencies, which he would then tune into live over the song Program. "Sometimes you'd hear a cheer go up when I finally hit one of the ones they really liked,” he says. "Randomly throwing the dial back and forth and hitting the different stations was part of the concept of that song.”

Divided Opinions

This photo was taken at an earlier, outdoor concert in New York City, again in 1968, "before the plywood configuration, where I just had all my oscillators, amps, pedals, and so on piled onto a table. There were 30,000 people in the audience — we were terrified!”

This photo was taken at an earlier, outdoor concert in New York City, again in 1968, "before the plywood configuration, where I just had all my oscillators, amps, pedals, and so on piled onto a table. There were 30,000 people in the audience — we were terrified!”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the reactions from their contemporaries to Silver Apples' unorthodox sound were wildly mixed.

"Most of them didn't like or understand what we were doing,” Simeon states. "Most of them thought we were out of tune and we weren't playing progressions that were considered rock & roll.”

New York jazz‑rockers Blood, Sweat & Tears, for one, were particularly vocal in their dislike of the duo's music. "They publicly stated after they played a gig with us, 'This band Silver Apples came on and we actually had to leave the dressing room, it was so awful.' On the other hand, Procol Harum, when we played with them in Chicago, I went to a radio station to do an interview with Gary [Brooker, singer] and he said over the airwaves that he thought we were possibly the most important thing going on in the United States that he had seen. So, y'know, there were people who got it. John Lennon got it. He said on British television, 'Watch out for a band called Silver Apples, they are the next thing.'

"But for the most part, people I think felt a little threatened by what we were doing. They thought synthesizers — even though we didn't really have a synthesizer, we just had a home‑made pile of electric junk — were gonna take away jobs and that people would be out of work because of them. So there was a general sort of hostility among traditional rock & roll musicians toward what we were doing.”

Jimi Hendrix, on the other hand, frequently jammed with Silver Apples during nocturnal sessions at the Record Plant in New York. "On many different occasions the engineer had the presence of mind to just roll the tapes and one of the times he got me and Jimi working on the Star Spangled Banner together. A segment of it was released on a posthumous box set [also to be found on YouTube as Anthem – Silver Apples feat. Jimi Hendrix]. It was listed as a solo by Jimi, when in actual fact, if you listen, you can hear me playing six bass oscillators behind three tracks of guitars he'd laid down.”

Given the highly unusual nature of Silver Apples' music, however, the recording of their key first two albums proved something of a struggle, for different reasons. Their eponymous 1968 debut, recorded in Kapp Records' four‑track studio, found them wrestling with the facility's limitations.

"It was really kind of laborious,” Simeon says, "because we had an engineer who had never recorded anything other than background piano music. Working with four tracks we had to do a lot of what we then called 'boiling down' to free up another track. So when time came to mix the songs, we had very little control over what we were doing. That's why you can hear occasional little blips or drum clicks or out‑of‑tune moments.”

For their second album, 1969's Contact, Silver Apples enjoyed the comparative luxury of Decca Records' 24‑track studio in Los Angeles. "We could record different parts of the song in different takes, which gave us a cleanliness for mixdown that we didn't have before. So yeah, it gave us more freedom. But we didn't have the freedom of time that we had on the first one. We didn't have time to sit back and pick it apart and redo this and redo that. So we ended up with pretty much just as raw a set as we had with the first one.”

In support of Contact, Silver Apples set off on their most extensive tour of the US. Given its makeshift nature, The Simeon stood up well to the rigours of road life. "It was always in pretty good shape,” says its creator. "Sometimes on stage, stuff would break or I'd see a broken connection or something. One time in Chicago, Danny and I did our soundcheck and everything was fine and we went out to get something to eat and when we came back we noticed that everything on the instrument had been changed. Which meant that the sound guys had all been on there and were monkeying with it. So nothing worked. Everything was out of tune, two or three things were actually broken. They'd really done a number on it. I had to get out the soldering iron and go to work before we could perform that night.”

Crash Landing

In a strange twist, it was the artwork for Contact that was to prove Silver Apples' undoing. While the front cover featured the duo in the cockpit of a commercial jet bearing the Pan Am logo, the back cover shot found them superimposed over a sourced photograph of a plane crash. Pan Am were not impressed.

"That was just a prank that kinda went astray,” Simeon says. "If I think about it now, it's really kind of dumb. We didn't mean any harm by it, but a lot of people were really pissed off about that. Pan Am wanted their logo on the airplane up front because they thought it would be free publicity for the airline. But on the back it was a picture of a European airplane crash and Pan Am of course felt like we were saying that their airplane had crashed. The whole thing was just misunderstood and misread by everybody.

"They sued us, big‑time. They sued Kapp Records, they sued us as a band, they sued us personally, they sued our management, they got some judge in New York to issue a cease‑and‑desist on us performing. All the records had to be taken off the shelves in all of the record stores. They put some sort of a lien on our equipment and they actually came to a club where we were playing and confiscated Danny's drums. Fortunately, my stuff wasn't there. That photograph led to the lawsuit that broke the band up. No record label would touch us from that point on. That was the end of Silver Apples.”

With a third album, The Garden, recorded on spec and shelved in the wake of the Pan Am debacle (though it would eventually be released in 1998), Silver Apples petered out in 1970. Taylor took a job at a telephone company, while Simeon returned to his first love as a visual artist, funding himself by working as a graphic designer for an advertising agency.

Then, in 1994, a German record label, TRC, released a bootleg CD featuring the first two Silver Apples albums, reigniting interest in the duo. "The next thing you know, all the record stores are carrying the CD,” Simeon says. "We didn't have anything to do with it.”

Back In The Business

In 1997, with three other musicians in tow, Simeon revived Silver Apples at a show at New York's Knitting Factory. As a major sign of the Apples' newfound cool, among the audience that night were Johnny Depp, Kate Moss, the Beastie Boys and Sean Lennon. "I was fresh off of not playing music for 20 years and didn't really have the confidence to just go out there and be me and a drummer again,” Simeon admits. "I felt like I needed backup at the time.”

Missing from the line‑up was Danny Taylor, who Simeon had been unable to locate. "At every single radio station where I'd do an interview, I would say, 'If anybody knows where Danny is, please have them contact the station,'” he recalls. "I did an active search for him all over the country and it finally worked. He heard his music being played on a station in New Jersey and that was it.”

Only three gigs after the original duo of Simeon and Taylor reunited, however, the pair suffered a road crash when returning from a gig in New York, which resulted in their van being rolled over and the former breaking his neck. "I'm still not fully recovered,” Simeon states. "I have some numbness in my extremities that's a result of the paralysis. If I put my hand in my pocket, I can't tell if I've got keys, coins, paper. But it hasn't affected my playing, in that I've always been a visual performer anyway. I've always used push buttons and colour‑coded keys and dials and numbers on oscillators. As a matter of fact, in some ways, because I had to re‑learn how to do everything, it's made me better because I worked harder at it. I think I'm actually a more proficient craftsman now at my trade than I was back then.”

Tragedy further thwarted Silver Apples when Danny Taylor died from cancer in 2005. "I just figured I could keep going,” Simeon says. "I didn't know how I would do it. So I just sampled the rhythms that Danny had already created and went out as a solo act. I have hours of two‑track tape of him practising his drums, all the patterns for each of the different songs, plus new stuff. So I'm able to just plug him in, pretty much. It's not like I'm recreating him in any way electronically. It's still Danny playing.”

In With The Old

These days, for touring purposes, Simeon has retired his old oscillators, sampling them into his Akai S20. "It's all the same sounds and I still basically play them the same – I don't have a keyboard, it's just push buttons, the same as it was with the telegraph keys. It's a lot easier for me to transport around and it's actually freed me up, so that I can stand up and play now. I never felt very comfortable sitting down and playing. So now I can stand up and work volume pedals with my feet, which I never could do before because I was always playing bass oscillators with my feet.”

Nevertheless, his live setup still contains one makeshift, Heath Robinson‑like element, in the form of a new triggering device he's built from a four‑inch length of PVC pipe, a door hinge and two intermittent switches bought from Radio Shack. Simeon's latest home‑made sound source is "a triggering device I made from PVC pipe and a door hinge from the hardware store and some on/off switches from Radio Shack”. "The door hinge is inside the piece of PVC pipe,” he explains. "There's an intermittent switch on the top of the pipe pointing inward and on the bottom of the pipe pointing inward, so if I push the door hinge up, I trigger the oscillator. So going up and down, up and down rapidly I can go d‑d‑d‑d‑d‑d and it sounds like a plectrum on a guitar. I'm surprised it took me this long to come up with it, but it's great in terms of doing little solos and things.”

Simeon's latest home‑made sound source is "a triggering device I made from PVC pipe and a door hinge from the hardware store and some on/off switches from Radio Shack”. "The door hinge is inside the piece of PVC pipe,” he explains. "There's an intermittent switch on the top of the pipe pointing inward and on the bottom of the pipe pointing inward, so if I push the door hinge up, I trigger the oscillator. So going up and down, up and down rapidly I can go d‑d‑d‑d‑d‑d and it sounds like a plectrum on a guitar. I'm surprised it took me this long to come up with it, but it's great in terms of doing little solos and things.”

Now settled in a home studio in Alabama, Simeon has fully embraced modern technology in his setup, using Sony's Acid Pro to record and Ableton Live 8 to program his performance sets. "In Ableton Live, I assemble the samples in a linear fashion. I pretty much lay them down like you would in an old‑fashioned way on tape. You can switch from Arrangement View to Session View back and forth, but I just like the Arrangement View more because, being a visual person, I like the way it's laid out in this linear form.”

Aside from touring, Simeon is currently working on what he calls a "Silver Apples opera”. "It's about a group of beings whose gene and cellular make‑up was altered by a cosmic event, a meteor slamming into earth many thousands of years ago,” he says.

In the meantime, his group's influence continues to grow, with Geoff Barrow of Portishead's new group, Beak>, in particular, paying homage to Silver Apples. "Some of the songs by Beak> are what he calls 'direct tributes' to Silver Apples,” Simeon points out, with no little pride. "I find it hard to get my head around that. To me, we were just limping along doing the best we could with our limitations in terms of the equipment we had and the abilities we had. I never thought of us as being ground‑breaking.”