Having proved his worth on Tate McRae’s second album, producer and songwriter Grant Boutin played a pivotal role in the third.

Released in September 2023, Tate McRae’s hit ‘Greedy’ helped steer her second album Think Later to platinum in the US and her native Canada. This year, McRae’s third album, So Close To What, went to number one in at least a dozen countries, including the US.

So Close To What has been Tate McRae’s most successful album yet.McRae’s first album, I Used To Think I Could Fly (2022), was made with famous writers and producers including Blake Slatkin, Charlie Handsome, Charlie Puth, Greg Kurstin, Finneas and Louis Bell, all of whom have appeared in SOS. Kurstin also featured on Think Later in addition to Ryan Tedder, lead vocalist of OneRepublic and one of the most successful writers and producers in the industry. Tedder has many writing and production credits on So Close To What, and other big names like Rob Bisel, Emile Haynie, Lostboy, Ilya and Blake Slatkin also contributed, along with the relatively unknown Grant Boutin. Boutin co‑produced five tracks on Think Later, including ‘Greedy’, and on So Close To What, he has writing and production credits on eight songs, including four songs on which he is sole producer. Moreover, Boutin was again involved with some of the big singles, including ‘Revolving Door’ and ‘Sports Car’.

So Close To What has been Tate McRae’s most successful album yet.McRae’s first album, I Used To Think I Could Fly (2022), was made with famous writers and producers including Blake Slatkin, Charlie Handsome, Charlie Puth, Greg Kurstin, Finneas and Louis Bell, all of whom have appeared in SOS. Kurstin also featured on Think Later in addition to Ryan Tedder, lead vocalist of OneRepublic and one of the most successful writers and producers in the industry. Tedder has many writing and production credits on So Close To What, and other big names like Rob Bisel, Emile Haynie, Lostboy, Ilya and Blake Slatkin also contributed, along with the relatively unknown Grant Boutin. Boutin co‑produced five tracks on Think Later, including ‘Greedy’, and on So Close To What, he has writing and production credits on eight songs, including four songs on which he is sole producer. Moreover, Boutin was again involved with some of the big singles, including ‘Revolving Door’ and ‘Sports Car’.

Planting Seeds

Growing up in San Diego, Grant was inspired to start making music by a very young Tom Norris, now one of the world’s top producers and mixers. (Norris, who was featured in SOS August 2020, this year collected two Grammy awards for his work on Charli XCX’s Brat.) “When I was a kid, Tom was my next‑door neighbour. I would often go over to Tom’s house, and he was an early teenager willing to hang out with an eight‑year‑old. He’d be making house music in Fruity Loops, and I thought it was the coolest thing I had ever seen, even as I was too young to understand what he was doing. When I was 11, I downloaded Fruity Loops, and started messing around with it.

“Tom was not only my introduction to Fruity Loops, but also to electronic music. He made me a CD with music by Pendulum and Junkie XL, and so on, that I listened to non‑stop during family vacations. My parents also required me to take piano lessons. I hated it when growing up, but by age 15‑16 I enjoyed being expressive at the piano. It made me a better musician than I would have been otherwise.”

The young Grant Boutin grew up fascinated by EDM and future bass in particular. “I listened a lot to Timbaland, and when I was making dance music, I never gravitated towards four‑to‑the‑floor stuff. I always wanted interesting syncopated drum rhythms. Whenever I tried a house track, I never felt inspired or that I had an edge in originality in that lane. So all I did was EDM. Whenever I created a cool groove and added some melodies on top, it felt fresh.

“As a teenager I developed the idea of combining chords and melodies with hip‑hop beats and electric music, but didn’t know how to achieve it. But when I heard Wave Racer in 2014, I thought, ‘Yeah, this is exactly what this combination should be, but I’m going to do it my way.’ Wave Racer was doing future bass, and I was into that genre really early. I watched it become big, and started my electronic project Grant Bowtie when I was in middle school. I signed with Monstercat, and released my music via them.”

Networking

The pandemic then steered Grant’s career in another direction. “I went to the USC Thornton School of Music where I did their Music Production Major. Straight after I graduated in 2019, Covid hit. I was living in downtown LA with a friend, stuck in a dark room with a window looking out at a wall. Until then I had only been doing my artist project, and dance music was dead at that point. I had been DJ’ing since the end of college, and really loved it. But no more live shows were happening.

“At the same time, I had been getting a bit tired of dance music. When it came to making a new sick drop, I wasn’t sure what to do that hadn’t been done 100 times before. The favourite parts of my tracks became the vocal sections that lead up to the drop. My old manager had also pushed me into exploring songwriting and production for others, so I started doing more collaborative sessions, and writing songs all by myself. I wrote tons of really cliché songs!”

Grant eventually came up with what he calls “some cooler stuff”, and managed to sign a publishing deal. In 2023, Lou Al‑Chamaa joined Avex Publishing as Senior VP and Head of A&R Publishing. He liked Grant’s stuff and put him in a room with fellow developing writer Coleton Rubin. The two wrote “a really cool song”, which Al‑Chamaa emailed to Ryan Tedder, who, says Grant, “became obsessed with the song and really wanted it for OneRepublic”.

That song, a ballad, has yet to be released, but Grant and Rubin contributed to another OneRepublic song, ‘Mirage’. Tedder’s company Runner Music partnered with Avex to publish Grant, and his career was beginning to take off. “Ryan started bringing me in for sessions, and found out that I could do other things too, like K‑pop, and that I could turn things around really quickly. One could say I was in a producer boot camp with him for the first year of working with him. He’d send me demos and things that he had started and asked me to flesh out the production more or just to try to make it sound more finished. He’s doing so many songs every day, he doesn’t necessarily have the time to tweak everything.”

One of the things that Tedder sent to Grant during that time was an early version of ‘Greedy’. “He sent it to see what I could come up with. I don’t think there were any instructions. It already had quite a bit of what’s in the final version, including the drums and the vocals, so I started filling up the ambience, swapped out some of the drums, and added more bits and pieces. My tendency is to overproduce and throw too many little sound bits into every crevice of the song. They ended up loving what I did for the chorus, because they wanted that really full, and they deleted everything I had added to the verses and pre, so there was a big contrast between the two sections.

“I thought it was a cool song, and I really got into a flow state when working on it, but I had no idea that it would become a single, let alone a global smash hit. Because it did, I was asked to come in to help finish several of the songs on Think Later. I showed up for the sessions at Ryan’s studio, and hung out with him, Amy [Allen], Jasper [Harris] and Tate. They’d all be leaning over my shoulder while I was at the computer, asking me things like, ‘Yo, can you make this synth sound really edgy, dark and gritty?’ and throwing out song references, and it all needed to happen in an hour. Honestly, it was really challenging. For a month I went to Ryan’s house every day, and did what I could to make these songs sound as good as possible and help finish them.”

Working with high‑profile producers and songwriters helped develop Grant Boutin’s existing ability to get sounds fast.

Working with high‑profile producers and songwriters helped develop Grant Boutin’s existing ability to get sounds fast.

Close Up

Grant was not part of the very first steps of creating So Close To What, but soon became deeply involved. “I think the songs ‘It’s OK I’m OK’ and ‘2 Hands’ might already have been in existence, and perhaps some others. Some songwriting had already been done. Then I did two sessions with Tate and Amy Allen. Tate had a very specific sound design request, and I guess I did a decent job of executing it. We wrote a really cool song, and that snowballed into me doing a lot of writing and production on the album.

“With the first album, I was mainly a finisher. I added a lot of cool creative elements to several songs, to service ideas that already existed. On the new album I got to start songs from scratch. I did as much preparation as I could for these sessions. My brain just shuts down if it’s like, ‘OK, time to make a hit,’ when there’s nothing to start with. So I connected with Ryan and Tate before sessions to talk about stylistic inspiration, and Tate would have playlists with the moods she was looking for. So at home I was making song starts and sounds and drum tracks for inspiration. Others came in with their own ideas as well. Ryan is really good at being aware of the big picture, while Tate knows exactly what she wants. She has so much inspiration all the time.

“‘Sports Car’ is one of the songs for which I came in with the beat, which was pretty much some form of the currently existing song. I was really leaning into an early 2000s lane, using the Phrygian dominant scale, which I have always liked, though Tate has shied away from that specific sound in the past. In trying to emulate early 2000s sonics I used many detuned saw‑wave hits, which I created using Xfer Serum. That lead thing in the intro of ‘Sports Car’ is a detuned single saw wave, going through reverb and then some plug‑in with tape wow after the reverb, to kind of glue and detune the whole thing.

Grant Boutin: When I did dance music, many of my drop lead synths included me humming a melody, and then formanting it a certain way, and layering it with a synth. Having a vocal element in a song offers nice ear candy, and it’s super fun to do.

“A lot of the bass stuff is Serum, layered with 808s, and me humming underneath. When I did dance music, many of my drop lead synths included me humming a melody, and then formanting it a certain way, and layering it with a synth. Having a vocal element in a song offers nice ear candy, and it’s super fun to do. It’s a creative thing of getting on the microphone, messing around, and seeing what you can come up with.

“I like to layer my vocals quite a bit, and I’ll usually have Melodyne on, so it’s in time and in tune with the other instances of the recordings. Sometimes I’ll formant it down or speed it up or pitch it, depending on what I’m going for. I’m also a big fan of the Output Thermal Interactive Distortion plug‑in. I run a lot of things through that, and just go through the presets, or tweak them a little bit. There’s really no exact method. Essentially I have no idea what I’m doing. I just start recording myself and throw weird effects on!

“For synth sounds I use a lot of [U‑he] Zebra, and I’m also a Native Instruments Kontakt library hoarder. I really like the Slate + Ash and Teletone Audio Kontakt libraries. But a lot of my secret sauce is not necessarily the synths or samples I’m using, but the way I treat them. I come from dance music, so I side‑chain all kick drums to some extent, using Cableguys ShaperBox. It’s part of my template. In a dance song, that side‑chain will dip the entire frequency spectrum, but if I’m mixing a song that needs to have a more transparent or gluey‑type punch, I’ll just dip the low end.

“Because of my dance music background, I want the drums to hit as hard as humanly possible. A friend taught me how to get a harder punch by simply drawing automation curves for every single kick. So every kick has volume automation going to zero, to maximise the transient. I do a lot of side‑chaining with Oeksound Soothe as well, mostly for vocal effects. I’m really detailed about delay throws and reverbs, also putting on choruses and tape effects and so on, though in pop music you don’t have the room to go really crazy in the same way with sound design and other elements because you don’t want to crowd out the vocal.”

Sporting Chances

Grant applied many of these working methods to ‘Sports Car’, the biggest hit from So Close To What. “I brought my beat for ‘Sports Car’ in after we had already written a full song that day. They heard that glitchy intro in the beginning, and were like, ‘Oh, that’s sick.’ Usually when I’m in the room with Tate, Ryan and Julia [Michaels], I tend to be at the computer, but when it’s just Tate and me, I’m also contributing melodic ideas. I’m not very helpful with lyrics, but particularly when Tate and I were at Jungle City Studios in New York later on in the project, where we wrote and recorded ‘Bloodonmyhands’ and ‘Like I Do’, I had a Shure SM7B next to me, and we’d both be ad‑libbing with Auto‑Tune and full vocal chains.

“At some point when working on ‘Sports Car’, Julia Michaels had the idea of doing a whisper chorus, like the Ying Yang Twins’ song ‘Wait (The Whisper Song)’ [2005]. We were all into that idea, but for a while Tate wasn’t sure. In the vinyl version of the song there is no true whisper‑only chorus, there’s a whisper with talking underneath it. That was how the song existed for a very long time. But Julia was really passionate about the whisper idea, saying it’s what makes the song. Eventually Tate hit me up one day and said, ‘Hey, let’s try it with the whisper again.’ After a few more versions and turning up bass sounds and incorporating some other requests, she was into the whisper as well.”

Grant also contributed a small but distinctive element to the intro. “One of my favourite things is the glitchy bit right before the song starts. It’s a bunch of small sound bites, like radio sounds and guys’ voices and all this stuff panning around. It’s microscopic and happens very quickly. Sometimes a song needs to have a really attention‑grabbing intro. I had no idea what to do for this one, so I simply threw some things together. For a while others didn’t want it in the song, and then everyone decided to keep it. I also added a guitar in the second chorus.”

The most essential element of the song, the vocals, were cut by Grant and McRae at Tedder’s studio. “Only towards the end, when Tate wanted to recut some lines, did we record at Westlake. Pretty much all Tate’s vocals that I recorded were cut with a Neumann U67 or U87, going through a Neve 1073 and then the Tube‑Tech CL‑1B. Pretty standard. My vocal chain in Fruity Loops also is very simple. I’ll do a high‑pass, and then have an Xfer OTT compressor, Waves RVox and CLA Vocals, a de‑esser, an exciter, and if there’s a resonance that is hurting my ears, I’ll add Soothe. One thing I do that people think is dumb is have Auto‑Tune baked into the track. But I don’t have heavy settings, and it saves a lot of time, especially with the Fruity Loops workflow.

“I’ve worked with artists that love to do 20 to 40 takes of each line, which to me feels a lot. With Tate, we go line by line. Sometimes she kills it on the first take. Sometimes we’ll do five, sometimes we’ll do 10, but it rarely is more. I do a lot of vocal doubling, grabbing takes that were good but not as good as the lead, and I’ll turn those into doubles. Sometimes I’ll pitch a vocal an octave down, and mix it in so you can barely hear it, but it’s reinforcing things. Another thing that I started doing is either manually turn all breaths down to super quiet before all the compression hits it, or I’ll separate them all out onto their own track and turn them down, just because when you’re compressing the heck out of a vocal, the breaths get super loud.”

Arriving At Perfection

Grant says he did “probably 50 versions” of ‘Sports Car’ as he and the others tried to arrive at the perfect result. “It’s probably the only time in my life I’ve put that much work in a song, and loved the song more at the end than when it started. Normally when I go through that many versions of a song, I’ll be sick of it, but ‘Sports Car’ was getting cooler all the time. Tate really drove that, and I really respect her taste and vision!”

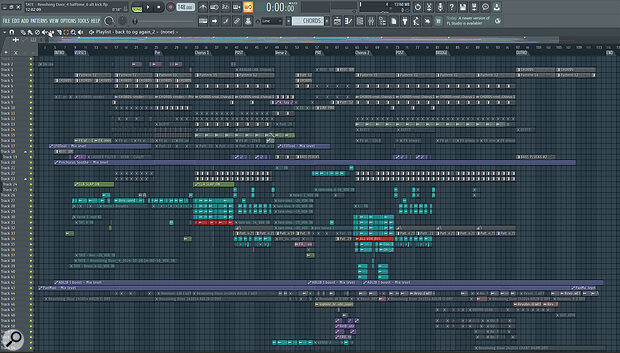

Unusually, Grant Boutin still works entirely in FL Studio. This screenshot shows the Tate McRae hit ‘Revolving Door’.

Unusually, Grant Boutin still works entirely in FL Studio. This screenshot shows the Tate McRae hit ‘Revolving Door’.

Throughout his work on the songs he was involved in, and for each of the 50 versions of ‘Sports Car’, Grant was creating rough mixes. He often did this back at his own studio, where he also has “Yamaha HS8 monitors, a Manley microphone, a Neve 1073 mic pre, a MIDI keyboard, my guitar and my bass, and Audio‑Technica ATH‑M50X and Audeze LCD‑X headphones. I like mixing on headphones. The Audeze LCD‑X phones are open‑backed and really good for mixing, but I’ve kind of stopped using them as much recently because I’m not the most skilled mixer as far the correct EQ curve for the general song is concerned, and because the Audezes are so forgiving on the ears and not super bright, I tend to mix overly bright on them. When I then put some normal consumer headphones on I’ll be like ‘Ah, this is hurting my ears.’ So what I do now is mix on my Audio‑Technica M50Xs, because they are a lot harsher. It stops me from mixing too bright.

“My go‑to plug‑ins during mixing are the Soundtoys EchoBoy and Valhalla delays, and the Valhalla Vintage Verb. I’ve recently also been getting into the Liquidsonics Seventh Heaven reverb. For more creative effects I love the Valhalla Super Massive, and the Shimmer. The latter has such a specific sound that’s great for Tate McRae’s stuff. She loves that reverb. She loves everything to sound airy and atmospheric, and the Shimmer can fill out space. It’s also really fun to suddenly go from a section of a song that is completely dry to sections with huge reverb tails. That is kind of an EDM‑ism as well. I got used to a sound where every breakdown before the drop had some eternal reverb sound on the vocal, and then suddenly that disappears.

“I’m always side‑chaining vocals to their reverbs because it can otherwise get really muddy, using Soothe for the higher‑frequency stuff. It kind of does what the Wavesfactory Trackspacer does. It notches the actual resonances, and is not dipping the whole thing. I also use a lot of chorusing and tape effects on everything, which I think are nice additions to electronic sounds to make them sound more warm and less purely digital. I love the Baby Audio tape emulation plug‑in, TAIP, which is supposed to be AI, and the Aberrant Audio DSP Sketch Cassette II. I’ll also use the Wavesfactory Spectre saturation EQ plug‑in a lot. I love clipping, and tend to clip all my drums, using the Kazrog KClip Zero plug‑in, and Decap’s Knock plug‑in. A lot of the drums in ‘Sports Car’ are pretty clipped.

“I have to make these rough mixes sound pretty finished and powerful, to get everyone impressed by them. I try to make everything pretty maxed out on the loudness scale and make sure everything is high‑passed when it needs to be. Plus everything’s side‑chaining and punchy and the vocals have to be sitting right. After that I count on a mixer to help me take it that next five to 10 percent, and of course, on Tate’s album we had great mixers like Serban Ghenea, Manny Marroquin — and Tom Norris!”

Against The Grain

Whereas the pro audio world is predominantly Mac‑based, Grant Boutin is a diehard Windows user, and works exclusively in FL Studio. “I’ve been using it for 15 years and I know all the hotkeys. It’s just what I’m lightning fast in. And deep down, there is this fun feeling of carrying the torch for Fruity Loops in the pop space. Every session I go to, my co‑writers say, ‘Whoa, I’ve never even seen someone use this program’ or ‘I didn’t even know you could record vocals in Fruity Loops.’ Sometimes producers will say, ‘Don’t worry, bro. I’ll cut the vocals,’ and I’m like, ‘Hang on, I can do it too!’

“I’m out there with my Windows PC with Fruity Loops, my Focusrite 2i2 interface, and my clunky wireless keyboard that looks like it’s from the ’90s. But I’ve always wanted a wireless mechanical keyboard, and I love it. It means I never have to readjust my brain to the layout of the laptop keyboard. When I go out to sessions it can be embarrassing when people want to AirDrop me stuff and I have to say, ‘Sorry, can you email me or send it via a file sharing website?’ There are some websites that let you do AirDrop between Windows and Mac, but they’re finicky and sometimes don’t work. So I’ll also bring a flash drive because it’s just too much of a pain to do everything to email. Sometimes I think I should get a Mac, but don’t know how to use one. I’ve been on a PC my entire life.

“I’m out there with my Windows PC with Fruity Loops, my Focusrite 2i2 interface, and my clunky wireless keyboard that looks like it’s from the ’90s...”

“I’m out there with my Windows PC with Fruity Loops, my Focusrite 2i2 interface, and my clunky wireless keyboard that looks like it’s from the ’90s...”

“Having said all that, there are some things that I wish were different about Fruity Loops. It’s like an endless blank canvas, where you can drag anything anywhere. None of the tracks conform to effects. You have to manually click each audio clip and assign it to a mixer track. It doesn’t have the same playlists and comping options as Pro Tools or Ableton, and because it doesn’t really matter where anything is in the arrangement window, it can get super disorganised very quickly. Recording audio in Fruity Loops can be a pain, but the fact that I don’t have to interrupt my workflow to switch DAWs makes it worth it.

“Despite the drawbacks I just described, Fruity Loops is totally capable of doing vocal production. I recorded almost all of Tate’s vocals on the songs I co‑produced on the new album in it. On the song ‘Sports Car’ I maxed out my Fruity Loops project. It was literally up to track 500! And probably 80 percent of that was muted vocals. I didn’t want to touch a single thing because I was so scared that I would mess something up.”