In its new Direct Note Access, the latest version of Celemony's Melodyne introduces what might just be the most hotly anticipated piece of music technology ever. Will mixing and remixing ever be the same again?

It's easy to forget how much of a revelation Celemony's original Melodyne software was when it first appeared in 2001. The quality of its central pitch/time manipulation engine generated a real sense of excitement amongst musicians on account of the new possibilities on offer. Since then, Melodyne has progressed through several stand‑alone versions, each refining the existing concept and ironing out wrinkles in the user experience. By the time a proper plug‑in version was announced at the end of 2006, and I personally joined the ranks of its regular users, the whole package was slick and mature, and it soon proved itself indispensable for my everyday audio‑buffing tasks.

However, the raw emotional impact of Celemony's first big technological 'hurrah' has inevitably faded in the memory, while the competition has upped its game. But then, at 2008's Frankfurt Musikmesse, inventor Peter Neubaecker pulled a whole new breed of rabbit from the sleeve of his conjurer's robe, in the shape of the flabbergasting new 'Direct Note Access' (DNA) algorithm. This is claimed to deliver what many had long considered an impossibility: the selective manipulation of individual notes within a polyphonic audio file.

Family Resemblances

It's taken Celemony until now, however, to make DNA available to the public as part of the new Melodyne Editor, which operates both in stand‑alone form and as a plug‑in for AU, RTAS and VST hosts. This replaces the existing Melodyne Plug‑in in their product line as part of a general reshuffle: Melodyne Uno will become the new Melodyne Assistant, Melodyne Cre8 will be absorbed into the next generation of Melodyne Studio; and Melodyne Essentials will advance to version 2. Anyone who purchased Melodyne Plug‑in after 12th March 2008 will be entitled to a free Melodyne Editor upgrade, while the watershed for free upgrade from other products is 1st June 2009. Other existing users can choose from a number of reduced‑cost upgrade options.

Various resolutions and formats of audio file can be loaded into Melodyne Editor's stand‑alone version, while the plug‑in requires that you first transfer your audio into the plug‑in in real time before you can get to work. After import, you have to wait while Melodyne runs its note‑detection analysis, following which the unravelled musical information is laid out in the editing window as a splattering of Celemony's trademark blobs on a piano roll‑style pitch display.

Three processing algorithms are available: the pre‑existing Melodic and Percussive settings, and the new DNA‑powered Polyphonic mode. As you'll know if you've already used previous Melodyne versions in earnest, the key to getting good results is to make sure that the software's note detection actually matches what you're hearing — it's pretty good, but it's not infallible, and if it fails to detect the notes correctly, the processing won't work as it should. Fortunately, you can control the way Melodyne interprets pitches in the audio, via a special Note Assignment mode.

With monophonic lines, the tidy‑up procedure is pretty painless. Usually there are just a handful of notes interpreted in the wrong octave, and it takes no time to correct these. Melodyne suggests sensible alternatives, and if you don't rate those you can just drag the errant blob in question to its intended pitch target. If you need confirmation that what you're seeing in the Note Assignment mode matches the musical line you're expecting to hear, you can now switch on a handy new Monitoring Synthesizer, which will play the detected pitches back to you in place of the source audio signal.

Detective Work

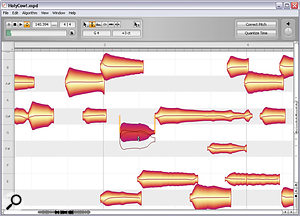

Melodyne Editor's Note Assignment mode, where you'll spend a good deal of time adjusting note detection when working with polyphonic audio. The little round orange slider under the tool palette allows you to decide how many of Melodyne's suggested note pitches are actually used for processing purposes. I'm moving the slider to the right here, so more note blobs are in the process of being activated.

Melodyne Editor's Note Assignment mode, where you'll spend a good deal of time adjusting note detection when working with polyphonic audio. The little round orange slider under the tool palette allows you to decide how many of Melodyne's suggested note pitches are actually used for processing purposes. I'm moving the slider to the right here, so more note blobs are in the process of being activated.

For polyphonic material, the detection process is more involved and time‑consuming, as befits the complexity of the task. Melodyne needs a precise map of all the notes in a given chord if it's going to adjust the pitch of one note without adjusting the others — if it detects only one note in a two‑note chord, for example, and you then try to shift the pitch of the one note it's detected, you'll end up shifting both pitches because it doesn't know that there's something it should be leaving untouched. Although Melodyne, again, does a remarkably good polyphonic detection job straight away, I've yet to have it guess everything right first time, so some time spent in Note Assignment mode is par for the course. Furthermore, because (for unspecified technical reasons) you annoyingly lose your Undo history every time you enter Note Assignment mode, you're best advised to deal with detection problems straight away, rather than leaving them until you're halfway through your actual processing.

First stop in Note Assignment mode should be the Note Assignment Slider, right underneath the editor window's tool area. This sets the overall sensitivity of the detection, potentially reducing the amount of detailed mouse work later on. Because pitch detection is anything but an exact science, Melodyne internally grades each of its detection predictions in terms of the probability that they're correct. The position of the Note Assignment slider's little reversed 'C' (which Celemony call the Crescent) determines how many of these predicted detection points are displayed, while the little ball (the Orange) determines how many are actively used as the basis for processing. Active note blobs sport the usual red/yellow colour scheme, while inactive notes are shown as faint grey outlines.

A second coarse adjustment tool is called (I'm not making this up) the Venetian Blinds. You can set high and low limits for the DNA note‑detection process, which can be useful for quickly eliminating extraneous out‑of‑range blobs en masse. These are upper and lower pitch limits outside which notes will remain inactive regardless of the setting of the Note Assignment slider. Once you've got the best from these tools, however, you can proceed to double‑click on any visible note to toggle its active/inactive status, irrespective of the settings of the Venetian Blinds, Crescent and Orange. (Am I the only one who finds this faintly Masonic?) While you're doing this, you can also add, remove or slide the little vertical Note Separation lines that Melodyne uses to indicate the boundary between one blob and the next.

You can set high and low limits for the DNA note‑detection process, which can be useful for quickly eliminating extraneous out‑of‑range blobs en masse. These are upper and lower pitch limits outside which notes will remain inactive regardless of the setting of the Note Assignment slider. Once you've got the best from these tools, however, you can proceed to double‑click on any visible note to toggle its active/inactive status, irrespective of the settings of the Venetian Blinds, Crescent and Orange. (Am I the only one who finds this faintly Masonic?) While you're doing this, you can also add, remove or slide the little vertical Note Separation lines that Melodyne uses to indicate the boundary between one blob and the next.

Occasionally a note does slip through Melodyne's net, though, most often in the higher registers, in such a way that it won't show up even with the Crescent at Crescendissimo. However, in this situation you suddenly find that a shadowy spectrogram trace surfaces in the vicinity of the mouse cursor, allowing you to sweep the mouse around and search for the spectrum peak corresponding to the missing note's fundamental frequency. When you find the sneaky devil, you can nail him down with a detection blob manually.  Sometimes a note that you can hear passes under the radar of Melodyne's automatic note‑detection routine. In this case you can browse a spectrogram of the audio (left screen), which appears a ghostly grey behind the note blobs, to find the spectral peak that corresponds to it and then double‑click to summon up a bespoke blob (right screen).

Sometimes a note that you can hear passes under the radar of Melodyne's automatic note‑detection routine. In this case you can browse a spectrogram of the audio (left screen), which appears a ghostly grey behind the note blobs, to find the spectral peak that corresponds to it and then double‑click to summon up a bespoke blob (right screen).

All in all, refining Melodyne's default note detection is a much bigger part of the job when working with polyphonic parts than when working with monophonic ones, but the tools available seem perfectly adequate for the job if you're ready to roll up your sleeves. The more I worked with Melodyne, the more I realised that there's a bit of an art to refining the DNA detection, because the exact start and end points of each active blob can make quite a big difference to the sonic results. In fact, subtle clicks can occasionally creep in when a Note Separation is in the wrong place, but by the same token I found that you could banish them again with a little careful blob massage in Note Assignment mode. I suspect that power users will differentiate themselves from the herd in terms of their experience in finessing operational aspects such as these.

Pitch, Time & Amplitude Tools

So far, so boring, because the fun only really starts once detection is sorted. In case you're not aware of what Melodyne can already do with monophonic audio, let me recap briefly. Pitches can be shifted and quantised (ie. tuned) relative to a wide range of scales, and you can edit the speed of each pitch transition if the default setting doesn't sound natural enough. Although pitch inflections are kept intact during straight pitch‑shifting, you can also scale or remove them, or just reduce longer‑term tuning fluctuations while leaving things like vibrato intact — the latter being one of my favourite Melodyne features. Formants can be edited independently of pitch too, which can help the naturalness of bigger shifts.

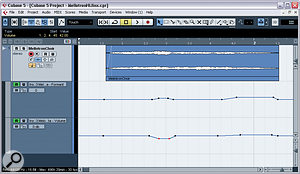

The Timing tool lets you stretch audio around like chewing gum, with reference to a selectable timing grid in the stand‑alone version, or your sequencer's beat map otherwise, and the overall playback speed can be sync'ed to after‑the‑fact sequencer tempo changes as well. And let's not forget the Amplitude tool, which adjusts the levels of selected notes, and can also mute them. On top of all those in‑editor facilities, there are also real‑time Pitch, Formant and Volume controls in the plug‑in incarnation, which can be automated from the host if you prefer to work that way.  In addition to the in‑editor tools, there are also real‑time Pitch, Formant and Volume controls in the plug‑in version of Melodyne Editor (inset) which can be automated from within your sequencer, as you can see in this screenshot from Steinberg Cubase 5.

In addition to the in‑editor tools, there are also real‑time Pitch, Formant and Volume controls in the plug‑in version of Melodyne Editor (inset) which can be automated from within your sequencer, as you can see in this screenshot from Steinberg Cubase 5.

This is all fairly old news, as far as the Melodic and Percussive processing modes go, and Celemony's quality pedigree in these areas needs no further props from me. The big question with Melodyne Editor is how well those same tools work with polyphonic files.

The Joy Of Access

I defy any audio engineer with a pulse to maintain 'U'‑rated language in their first response to what Melodyne Editor can do with polyphonic audio — I was certainly unprintable for a good half an hour, and I'm still struggling to hit 12A even after a long cooling‑off period! It's not that the processing is perfect (of which more in a moment), but that at its best, this software opens up a whole new array of intoxicating possibilities all at once.

While it's a safe bet that most people's first experiments will involve mangling the fabric of pitch and time with gay abandon, what will surely make up the majority of real‑world usage will be troubleshooting, and here are new vistas aplenty. Maybe your acoustic guitarist's instrument slipped out of tune during tracking? You can now snap it back into alignment. Maybe your Mellotron's tape mechanisms have seen one too many cape‑wearing prog maniacs? Pitch Modulation and Drift tools to the rescue! Maybe your pianist's a bit heavy with her right thumb? Highlight those notes and use the Amplitude tool to rebalance them. Rhodes player's ill‑advised soloing clashing with your song's harmonies? Break his hands. Or alternatively, let Melodyne drag the pitches somewhere more sensible, you sissy.

Looking at the more creative side of things, the biggest bombshell for sample‑based musicians is the way that DNA enables you to fit pre‑recorded loops and one‑shots together with a much wider choice of song harmonies. In particular, the effectiveness with which you can shift or mute a couple of notes in a polyphonic sample is fantastic, because that's often all you need to make things sit in your arrangement. The note muting is also great for thinning out chord voicings in things like strummed acoustic guitar parts, and it even did sterling service removing some pitched guitar spill from a piano recording. On the other hand, if you're after more notes in a given part, rather than less, the new copy/paste function lets you add those too, so you can patch up missed or mis-hit notes within a performance, or add whole new harmony voices.

Although Celemony are at pains to point out that DNA is still only designed to process individual instruments, the reality is not exactly cut and dried. For a start, ensembles of similar solo instruments (such as a string quartet) are fair game, and larger unified ensembles (like string orchestra) also turn out to be receptive to a small amount of DNA editing in practice, even though multi‑player ensemble sounds traditionally wreak havoc with pitch/time processors. On the other hand, 10 minutes' work is all it should take to convince anyone that meaningful tinkering with complete mixes is still within the realms of fiction, even if you choose something with a fairly homogeneous texture, although I'm sure that electronic musicians content with heavier processing artifacts will achieve serious mileage along that particular avenue nevertheless.

The Sound Of Doing Nothing

Now I'd love to spend the rest of this review just gushing about all the cool things DNA can do, but it's just as important to qualify how good it sounds and how far you have to push it before it begins to break out in a sweat. Well, the first thing to say on this score is that the Polyphonic encoding itself, even without any pitch/time processing at all, changes the sound of your audio, perhaps most noticeably by decreasing the general sense of high‑end 'air'. Some compensatory post‑Melodyne EQ is actually a pretty good fix in this respect, but another, thornier side‑effect to deal with is that transients in the audio signal tend to be smeared slightly in time, losing some of the sharpness of their attack. This shouldn't surprise anyone familiar with other pitch/time processors, as it's a problem all software developers come up against, but it's as well to make clear that even Celemony haven't quite cracked that particular nut yet. Clearly, the importance of this side‑effect will vary depending on how much transient information you're dealing with: pianos, harps, acoustic guitars and especially tuned percussion will pass less transparently through Melodyne than things like strings and slow‑attack synth pads. Again, though, there are some practical tactics that ameliorate the situation if it really bothers you — for example, I found that gently high‑pass filtering the un‑Melodyned signal at 10kHz or so and then mixing a little of it back in alongside Melodyne's output was quite nifty at restoring lost pick/finger definition in acoustic guitar and harp parts, even when I was doing a fair bit of pitch rearrangement.

To be honest, though, I'm not sure how much the vast majority of ordinary users will actually care about all that. Yes, the audio coming out of Melodyne Editor is always going sound subtly different from what went in, and I might hesitate to rely on DNA processing for bright, exposed lead instruments, but for most polyphonic parts in a typical mix, the encoding artifacts will be to all reasonable intents and purposes inaudible, and a piffling price to pay for what Melodyne has to offer, especially given that no‑one listening will know what the unprocessed file sounded like in the first place! Certainly, if you encounter something that only Melodyne Editor can fix, there's little doubt in my mind that the cure will be a hell of a lot better than the disease. It's also worth saying that inaccurate detection makes any encoding artifacts worse, especially if there are more notes detected than are actually present in the file, so reserve your own judgement on this facet of Melodyne's sonics until you've adjusted any such errors.

Timing Edits: The Good, The Bad & The Ugly

Once you get into the actual processing, it's the Timing tool which seems to me most likely to drive Melodyne Editor's artifacts outside the realms of acceptability, specifically with regard to transients. As long as a note is clearly separated in time from the others, such that its individual transient is well defined, time adjustments can work incredibly well — I was amazed at how effectively I could change the pattern of notes in a simple arpeggiated guitar part, for instance. The problems really start, however, if you try to separate two (or more) detected pitches that happen roughly at the same time. In some cases, I found that the transient appeared to follow one of the notes but not the other, while more often than not, the transient was all but obliterated and replaced by the kinds of high‑frequency digital swirlings I associate with over‑zealous FIR‑based noise suppression.

Editing note durations tended to cause fewer artifacts, and even with files that raised a stink for note‑position changes, I was able to edit note sustains over a wide range before the digital sprinkles became too noticeable. The combination of this and the level manipulation supplied by the Amplitude tool was brilliant for rebalancing and rephrasing the polyphonic voices within complex guitar and piano parts, so it'd be a big mistake to write off the Timing tool entirely just because you initially encounter some resistance when repositioning notes — it can still work real magic within its comfort zone.

One final issue with the Timing tool is that the review version had no facility to reset timing changes made to selected notes, despite all the pitch‑, formant‑ and volume‑reset options being present and correct. Celemony tell me that it's one of the things they're planning to implement very shortly (and it's already mentioned in the manual), but until it's there you'll want to be a little careful using the Melodyne Editor plug‑in, because every time you close your project it jettisons the Undo history. This is a bit of a pain in general, but especially if you can never return notes to their default time positions.

Rebalancing & Muting Notes

The Amplitude tool shines in a lot of circumstances, and can be used for moderate rebalancing (say ±3dB) with very few limitations. Once you need more control, however, it does find some situations more challenging than others. The first thing I noticed was that when I tried to turn down the level of one note sounding simultaneously with others as part of a chord, the note's transient sometimes wasn't affected as much as its pitched elements, giving a slightly unmusical result. Where this problem occurred, I was occasionally able to improve matters by adjusting Note Separation boundaries, but it was a bit of a lottery, so you might have to settle for volume‑scaling whole chords in some cases rather than individual notes.

Probably the most exciting aspect of the Amplitude tool, though, is the way it can completely mute notes, and it was able to do this so adeptly in some circumstances that I could barely believe my ears! It worked less well for isolated notes in sparser arrangements, but in busy parts such as guitar strumming, the results were uncanny. When it worked less well, the first giveaway was often a ghostly remnant of transient (or other accompanying noise component) that couldn't quite be removed, although if you don't pay enough attention to tidying up the initial note detection you're much more likely to get an occasional unattractive 'hollowing out' of some of the unmuted notes too. This is because, if an undetected note shares harmonics with a muted note occurring simultaneously, the DNA processing understandably strips away some frequencies that you'd rather it didn't. In this respect you have to be especially careful when muting bass notes, as removing the harmonics of these can have an impact on all the other notes above. However, if you do your homework, completely removing the bass line from a sample loop is often a reasonably realistic goal, which should gladden the hearts of remixers everywhere.

Once you hear how well Melodyne can zap single notes, there's an immediate urge to keep muting things to see how far you can get. What quickly becomes apparent, though, is that the artifacts multiply as you extract more and more frequencies from the source audio, and in my experience, you'll struggle to kill more than about 30 percent of the notes without the remainder sounding like they're coming down a drainpipe from a broken radio. And if you're successful in getting rid of the bass line, I wouldn't bank on being able to toast any other notes at all.

The copy/paste function can be astonishingly successful at adding in new notes or substituting duff ones, and this is one real highlight of DNA that Celemony haven't made a huge fuss about. Clearly, if you try to paste something into a completely different context, the results won't be completely smooth, but in many of my tests this feature was nothing short of miraculous, even when I was changing the pitch of the pasted note into the bargain.

Polyphonic Pitch Manipulation

So much for Timing and Amplitude; it's the Pitch tools that every jobbing mix-fixer will be drooling over. If you're expecting to shift pitches around as freely in Polyphonic mode as you can in Monophonic mode, think again, because the sound often starts becoming unpleasantly modulated (almost like a chorus effect) once you shift any note beyond a couple of semitones, and in some cases even a semitone shift caused me problems. When you first start experimenting with DNA pitch processing, it seems very hit and miss in terms of how well you'll be able to get away with shifting a given note, but after a while you do begin to get a feel for what might work and what probably won't.

For example, electric piano, Hammond, Mellotron, strings, pedal steel guitar, and most acoustic guitars appeared to be comparatively forgiving in this regard, while acoustic piano and driven electric guitars gave little away for free. (For the latter, I think you'd probably get better results working with a DI signal and then re‑amping that, rather than processing the amped version.) If a note is buried in amongst a more complex texture such as guitar strumming, that also seems to make it easier to get away with changing its pitch, whereas the low and high extremes of the texture don't usually fare so well.

For me, though, the strongest suit of the Pitch tools is undoubtedly tuning correction. Here, because the amount of pitch‑shifting concerned is comparatively small, the results can be truly remarkable, and even if you do very occasionally get a bit of unnatural waveriness sneaking in, the part's still going to be more usable that way than if it were out of tune! What's more, the fact that the Pitch Drift and Pitch Modulation tools are on hand means that you can sweeten the innards of each individual note as well as just adjusting pitch centres, something I found great for strings. For instance, with a quartet recording I was usually able to eliminate the vibrato of individual notes at will with no audible side‑effects. As with previous versions of Melodyne, though, you do still need to trust your ears over your eyes when judging if something's in tune or not, because Melodyne's interpretation of a blob's perceived pitch centre won't always precisely correlate with yours.

Finally, there's the Formant tool to consider. This is an aspect of the program I've always previously found yawn‑inducing, but which takes on a whole new lease of life here. In previous versions of Melodyne, the Formant and Amplitude tools were basically worthy but dull. However, they get a new lease of life here, courtesy of Direct Note Access. With formant adjustment (above right) you can adjust a guitar recording for fluffed notes and tired lower strings, while the Amplitude tool's muting facilities can very effectively thin out the texture to suit chord clashes or just a busy arrangement (above left).

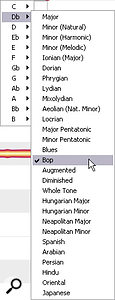

In previous versions of Melodyne, the Formant and Amplitude tools were basically worthy but dull. However, they get a new lease of life here, courtesy of Direct Note Access. With formant adjustment (above right) you can adjust a guitar recording for fluffed notes and tired lower strings, while the Amplitude tool's muting facilities can very effectively thin out the texture to suit chord clashes or just a busy arrangement (above left). By default, you edit note pitches in Melodyne Editor with reference to an equal‑tempered chromatic pitch grid, but there are numerous other scale‑based options that can speed up editing in a real musical context. Correct over‑zingy misfires in finger‑picked guitar, compensate for a single dull‑sounding guitar string, give the lower line in a polyphonic part more cut‑through in the mix; all this and more makes the Formant tool something of a hidden gem for mixing work, in my view, especially as you can get quite extreme with the settings before any real artifacts spoil the party.

By default, you edit note pitches in Melodyne Editor with reference to an equal‑tempered chromatic pitch grid, but there are numerous other scale‑based options that can speed up editing in a real musical context. Correct over‑zingy misfires in finger‑picked guitar, compensate for a single dull‑sounding guitar string, give the lower line in a polyphonic part more cut‑through in the mix; all this and more makes the Formant tool something of a hidden gem for mixing work, in my view, especially as you can get quite extreme with the settings before any real artifacts spoil the party.

The Editor's Choice

We were hoping to get our hands on the release version before going to press, but in the event I worked with a late beta, and I can't truthfully say that it was completely stable, either running stand‑alone or in VST plug‑in form within Cubase 5. I had maybe half a dozen crashes per day from it, usually with larger files that needed in‑depth Note Assignment tweaks. It remains to be seen whether this will still be an issue in the release version. Like the missing timing reset function, though, I'm pretty confident that Celemony will iron any stability problems out in due course, given their track record in this department. I'd nonetheless advise giving the demo a good going‑over to ensure sufficient reliability on your own system.

Frankly, though, neither this instability nor any of the processing limitations discussed above significantly undermine the importance of this product. Even in this fledgling incarnation, what Celemony's Direct Note Access can already do is simply breathtaking, and represents a major turning point in the development of studio technology. What's more, Celemony could probably have named their price with a product as hot as this, so it's brilliant that they've kept the new technology in the same price range as the old.

But it's not just DNA's power/pricing ratio that makes me slightly giddy, it's the potential wider ramifications too. How much might a tool like this change the music-creation process itself, and indeed the development of new styles of music? What impact will such audio fluidity have on copyright law? How long will it take before Celemony offer similar control over complete mixes? Or come up with a way to extract individual parts from a mixed file? (Breathe into the bag, Mike... Nice and slow now...)

Alternatives

You've got to be kidding!

MIDI Transcription

The stand‑alone Melodyne Editor has the facility to export a MIDI file of the notes detected by the Direct Note Access technology. Here you can see a polyphonic audio file and the corresponding MIDI file side by side in Steinberg Cubase 5.

The stand‑alone Melodyne Editor has the facility to export a MIDI file of the notes detected by the Direct Note Access technology. Here you can see a polyphonic audio file and the corresponding MIDI file side by side in Steinberg Cubase 5.

One useful little side‑feature in the stand‑alone version of Melodyne Editor is that you can export detected DNA pitches, timings and volumes in the form of MIDI Note data, as a Standard MIDI File. This would be great for situations where you found that a recorded track was completely beyond repair, and hence decided to replace the track with a MIDI‑triggered part. Alternatively, you might just want to layer a programmed instrument alongside an existing live track, or export the notes to a score editor to generate sheet music. In short, this is a nice little function, although it does usually work best with audio that has definite attack transients in it; otherwise, the timing of the MIDI file tends not to match the audio very closely.

Interface Refinements

In the process of creating Melodyne Editor, Celemony have overhauled not just the processing code, but also the whole program shell, partly to take advantage of progress in the field of multi‑thread processing on multi‑core computers. While they were at it, though, they included several other welcome refinements. For example, you can now freely drag the size of the editor window, rather than having to set its size from the preferences, and you can also audition notes within Melodyne while you're editing them, either in the context of their chord or soloed.

Hear DNA In Action!

There's only so much that words can convey about a product like this, so I've placed a selection of audio demonstrations on the Sound On Sound web site at /sos/dec09/articles/dnaexamples.htm to allow you to judge for yourself the quality of Melodyne Editor's Direct Note Access processing.

Pros

- Direct Note Access takes long‑established preconceptions about how audio can be processed, and then tramples all over them!

- Subtle rephrasing, rebalancing, retuning and timbral shaping of individual notes with polyphonic audio can now be achieved with minimal processing side‑effects.

- Phenomenal potential for creative copy/paste, remix and sound‑design work, especially in situations where you're less worried about digital artifacts.

- Extraordinary value for money, and a free upgrade for many existing users.

Cons

- If you need natural‑sounding edits, don't expect to push the processing as far in Polyphonic mode as you might expect to in Monophonic mode.

- Some documented features have yet to be implemented.

- Pre-release versions tested were prone to crashing, although not often enough to stop me getting serious work done.

Summary

Direct Note Access takes the editing of polyphonic audio to an unprecedented new level, and at a UK price which puts a country mile between Melodyne Editor and any of its competitors. Yes, the current implementation has its fair share of rough edges, but that's not the point. This is the future. Get with it, or get left behind.

information

£299; Melodyne Assistant £169; Melodyne Studio £599. Prices include VAT.

2twenty2 +44 (0)845 299 4222.

$349; Melodyne Assistant $249; Melodyne Studio $699.

Music Marketing +1 416 789 7100.

Test Spec

- Celemony Melodyne Editor v0.9.3.67.

- Steinberg Cubase v5.0.0.

- Rain Recording Solstice O3 PC with AMD Phenom II X4 810 quad‑core 2.61GHz processor and 4GB DDR2 RAM, running Windows XP Pro with Service Pack 3 v3264.