Although it certainly does sample, Roland's breakthrough 'Variphrase Processor' is far more than just a sampler — it offers a host of 'elastic' real‑time pitch‑shifting and time‑stretching options the like of which have never been seen before. Derek Johnson & Debbie Poyser stretch the limits of sonic processing with the unique new VP9000.

<!‑‑image‑>First shown at the January 2000 NAMM show in Los Angeles (see SOS April 2000), the VP9000 Variphrase Processor attracted its fair share of attention, and many of those who saw it were intrigued by a product that doesn't fit into a familiar category. Is it a sampler? Well, yes, it samples, but it lacks some of the features we've come to expect from a modern sampler, while it has other powers not currently seen in other machines. Is it a vocal processor? Again, yes — it has effects and can perform 'gender‑bending', as do some of the popular Digitech Vocalist processors, not to mention allowing you to add harmonies — but its applications are by no means confined to vocals. Is it some kind of groove machine? It's certainly capable of manipulating audio to create a range of trendy effects, all in real time, and possesses loop‑synchronising powers, but it also has applications that would indicate that it's rather more serious than a groovebox‑style instrument. Clearly, then, this is not an easy machine to sum up. One can't even readily categorise it according to its likely uses, since it probably has as many applications as individual purchasers (see the 'Who Will Buy...?' box for a few suggestions as to who might find the VP9000 particularly interesting, though).

Introducing 'Elastic' Audio

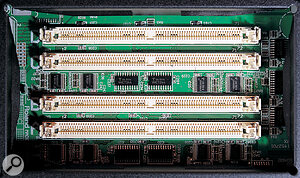

Extra RAM in the form of standard SIMMS, up to a maximum of 128Mb, can be added in the slots under the plate on the top panel of the VP9000.

Extra RAM in the form of standard SIMMS, up to a maximum of 128Mb, can be added in the slots under the plate on the top panel of the VP9000.

The Variphrase is dedicated to capturing audio, and then — as Roland put it — making it 'elastic'. Basically, this means that you are allowed to independently manipulate and play with the essential elements of the captured sound: the pitch, tempo, timing (groove), and formant content (see 'What's In A Voice' box). All this is possible in real time and, if you use the VP carefully, with high quality and minimal artifacts. Sample pitch can be altered without affecting tempo; tempo can be altered without affecting pitch; rhythmic loops can be automatically 'regrooved' according to four onboard groove templates, to give them a different feel; the pitch information can be removed from a solo phrase, so that it can have a new tune imposed upon it from a keyboard; and the formant content of vocal and solo instrumental samples can be changed to, for example, make a female vocal sample sound like a male. Formant control is the key to the Variphrase's ability to do without multisampling, allowing a single‑note instrument sample to be played over a much wider range than would be possible with a conventional sampler. Lawless types given to 'borrowing' sounds off records, where it's sometimes difficult to obtain more than one isolated sample of a given sound, could find the Variphrase very attractive for just this ability. Normally, even if you are able to find four or five usable notes in a performance, they won't necessarily match in tone or character, so the chance to make one note stretch could be very valuable.<!‑‑image‑>

Outside In

Dominating the front panel of the 2U rackmounting VP9000 is a large, bright‑blue LCD with six accompanying 'soft' function keys which activate items in the display. Six buttons to the left select the machine's various modes: Sampling, for recording audio; Sample, where samples are edited (why not call it 'Edit'?); and Performance, where up to six Samples can be arranged in a single onboard Performance for multitimbral playback, with their respective MIDI channels, key ranges, level and pan settings, and so on; Utility, for memory management operations such as copying, moving and deleting samples; System, where global functions such as display contrast (and backlight saver), overall MIDI settings, autoload and master tuning settings are defined; and Disk, for loading and saving data to disks in the internal 250Mb Zip drive or a connected SCSI hard drive. Six further buttons switch the reverb, chorus and multi effects on and off, Preview the current Sample, change the function of one of the three centre‑detented control knobs on the right of the front panel between two different tasks, and access a window where parameter ranges for the control knobs are set.

What VP9000 users will find their hands on most often is those three control knobs on the right, which work on individual samples or an entire Performance: Pitch, to adjust sample pitch (up to an octave up or down), Time, to alter sample playback speed (half at one extreme, double at the other), and Formant/Groove, which, depending on how it's set up, either changes a sample's formants or progressively alters a rhythmic sample's feel, for regrooving. The remaining group of controls to the right of the display, including an alpha dial, is used for OS surfing and parameter changing.

At the back there's a connector for the built‑in power supply, two balanced jacks for the stereo sampling input, with accompanying three‑way gain switch (‑20, ‑10, and +4dB), three stereo output pairs, and digital I/O in the form of both co‑axial and optical S/PDIF. SCSI comes as standard, on two connectors (a 25‑pin D‑sub and a 50‑pin port), and there's MIDI In, Out and Thru to finish off. On the front panel there's a further mono input for quick and easy sampling, and a headphone socket. If a CD writer is attached to one of the SCSI ports you can write the contents of Zip disks to CD‑R, for economic backups. The VP9000's standard 8Mb RAM quota can easily be upgraded, and unlike some machines you never lose access to the fitted RAM even when the maximum additional 128Mb is installed. The requisite sockets are hidden under a panel on top of the unit.<!‑‑image‑>

Facts & Figures

The VP9000 provides many features sampler users will be familiar with. Here, a loop point is being edited.

The VP9000 provides many features sampler users will be familiar with. Here, a loop point is being edited.

Although the Variphrase shouldn't be viewed just as a sampler, it nevertheless does much of what a sampler does. Compared to other samplers out there, though, it's been considerably souped up in the areas we've already mentioned, and pared back in others; it's only 6‑voice polyphonic and 6‑part multitimbral, and polyphony is reduced further with stereo samples, which take up two voices. The maximum length of a single sample is 25 seconds stereo or 50 seconds mono, which is the total amount of sampling time available from the fitted 8Mb of RAM. Even if the maximum extra RAM is added, in the shape of standard SIMMs, for a total sample time of more than seven minutes stereo, a single sample can't get any longer. You can't reduce sample rate to squeeze more out of the RAM, either, as 44.1kHz is the only rate available internally. Samples imported at other rates are automatically converted to 44.1kHz, 16‑bit.

The canny amongst you may be looking at those figures with a puzzled expression. Surely 44.1kHz, 16‑bit samples occupy 10Mb of RAM per stereo minute? So shouldn't 8Mb of RAM yield more like 50 seconds of stereo sampling rather than mono? This question highlights a crucial aspect of how the VP9000 works, and the impact this has upon sample time.

Getting audio into the VP9000 ready for manipulation isn't just a matter of recording it, as with conventional samplers: there's an additional step, called 'encoding'. This is the analysis phase that allows the VP9000 to get to know your audio so well that it can subsequently stretch it around like toffee (see 'The Clever Bit' box on page 148). The process takes under 10 seconds for a 2‑bar stereo loop, and after it's completed you have all the benefits of real‑time audio manipulation. However, encoded samples occupy 1.7 times as much space as normal ones, which explains why that 8Mb of RAM seems less roomy than you'd expect.

Step By Step

Despite the VP9000's inner complexities, the back panel is pretty straightforward, with only S/PDIF digital I/O (on optical and co‑axial connectors), a pair of analogue stereo ins, three pairs of analogue stereo outs, the usual MIDI trio, the two flavours of SCSI socket, and the IEC power connector.

Despite the VP9000's inner complexities, the back panel is pretty straightforward, with only S/PDIF digital I/O (on optical and co‑axial connectors), a pair of analogue stereo ins, three pairs of analogue stereo outs, the usual MIDI trio, the two flavours of SCSI socket, and the IEC power connector.

When recording samples with the VP9000 from scratch, the initial experience is similar to using an ordinary sampler. In the sampling setup page you choose stereo or mono sampling and which of the analogue or digital inputs will be used; there's an option to resample the VP9000's output, complete with effects, too. You can also predetermine a sample's playback pitch (ie. the key that plays it back at normal pitch), and set up input gain, with the latter selectable via software or a front‑panel knob. Sampling can be initiated manually, via a user‑definable trigger level, or with a MIDI 'sequencer start' message, and a metronome allows you to play to a given tempo, for ease of tempo matching later. A handful of capable 'pre‑effects' allow incoming audio to be processed with a noise suppressor, compressor plus noise suppressor, or limiter plus noise suppressor. Compression and limiting obviously have their uses (if a vocalist is singing directly into the VP9000, for example), and the noise suppressor is handy for sampling from noisy cassette or vinyl. Usefully, the software gain control can also be applied to incoming digital audio, as can pre‑effects.

One nifty feature of the VP9000's sample‑recording page is its 'template' facility, allowing instant selection of preset record settings. Eight factory templates are available, covering common sampling situations such as recording direct from a mic and recording from CD. These are editable, too, so if almost all the settings of a template are perfect for your purpose, you can just tweak the unsuitable ones. Eight user templates can also be saved.

For those for whom sampling is a black art, samples from CD collections can be imported, via the 'disk' page. The VP9000 saves its samples in WAV format, and can import WAV and AIFF samples, plus samples in Roland S700‑series and Akai S1000 and S3000 formats. We successfully copied samples created on a Mac to a VP9000‑format Zip cartridge and loaded them into the VP9000. Once an external sample has been loaded into the Variphrase, the procedure for editing, encoding and customisation is the same as for samples captured using the machine.

<!‑‑image‑>The Variphrase has a stripped‑down but very usable set of editing features: topping and tailing, cutting and pasting, reversing, dividing (into two sections), looping and normalising functions are all available, with screens that use the LCD to good advantage. Though you only ever see one waveform (even if e diting a stereo sample), it's still possible to zoom in on two axes to make fine‑tuning a doddle. In this way, precise cuts can be made, and accurate loops applied. There's no autolooping, but there is a zero‑crossing facility that helps to find a cut or loop point that won't cause a click.

It's best to assign a tempo to audio such as loops or longer vocal samples during editing, to facilitate tempo‑related operations later on, but if the audio's tempo is unknown you can simply tell the VP9000 its time signature and its length in bars or beats, and it'll work out the tempo for you — excellent. Even more wonderful is the fact that when the VP9000 knows a sample's tempo it can achieve the seemingly impossible trick of automatically playing disparate samples of varying tempos all at one master tempo, with virtually no user assistance, as long as the samples to be synchronised have the 'Tempo Sync' parameter activated. The VP can even sync sample tempo to incoming MIDI clock. The days of manually time compressing/expanding individual loops of different speeds to fit with each other are over for VP9000 owners.

Cracking Encode

Once a sample has been recorded, various playback parameters can be switched on, including looping and 'Robotize' (see page 147).

Once a sample has been recorded, various playback parameters can be switched on, including looping and 'Robotize' (see page 147).

After you've created a sample, it has to go through that most crucial part of the VP9000's business: encoding. Because you can put so many different types of audio into the VP9000, from a solo instrument to a complete stereo mix, there are three different encoding algorithms, dubbed Solo, Backing and Ensemble, each of which aims to ensure the best result for a particular kind of source sample material. The encoding algorithm you use also dictates which of the four sound parameters can be tweaked for that sample.

<!‑‑image‑>• Solo encoding is advised for lead vocals or instrumental solos. Once encoded, a Solo sample can have its pitch, time (playback length) and formant content tweaked in real time, but it cannot be regrooved.

- Backing encoding is designed more or less for drum and rhythm samples (and instruments with a clear attack, says the manual), and the encoded result can be regrooved and have pitch and time changed, but can't be formant‑tweaked.

- Ensemble encoding is described as suitable for samples with smooth changes in tone, but is in practice the best option for fully mixed audio. As with the Backing algorithm, Ensemble allows regrooving, pitch and time changing, but not formant changes.

Encoding isn't a process the user has much interaction with; other than choosing an algorithm, all you can do is alter a Depth parameter, but still it's a parameter worth having. Here's why. As part of encoding, the VP9000 analyses a sample for changes in level, and inserts an 'event' at each peak; these 'events' can be used in one keyboard mode to divide a sample, the divided parts then being assigned to consecutive keys — ideal for accessing individual hits in a drum loop, or cutting a vocal line into separate words or phrases. (Obviously, in this mode a keyboard can't be used to change the pitch of the bits of sample, because it's being used to trigger them.) The Depth parameter seems to affect how many peaks the VP9000 detects. The default setting works for most typical rhythm loops, picking up the hits you'd expect, but if for some reason this doesn't happen, increasing Depth makes the 9000 look for the less obvious peaks. When a sample has been encoded, the inserted events are visible in the LCD — a bit like Cubase VST 's audio quantising 'match points' — and can be manually moved with the alpha wheel and/or deleted. You can even add new ones with the press of a soft key. With some audio, such as a vocal sample with few obvious peaks, manual event insertion would be the best method.

On the whole, the encoding algorithms work well, but occasionally the one that seems correct to use turns out inappropriate. For example, we sampled a rich, filter‑swept monosynth in Solo mode and found that playing it back at anything but the original pitch resulted in an aliased, garbled sound, maybe because the frequency content of the synth sound was too complex for that algorithm. Using either of the others worked fine, as did sampling a simpler synth sound with Solo mode. You're free to use the wrong algorithm deliberately, but the result isn't usually pleasing!

Play It Again

Fine control is offered over the extent to which (if at all) the real‑time knobs affect the Pitch, Time, Formant, and Groove settings.

Fine control is offered over the extent to which (if at all) the real‑time knobs affect the Pitch, Time, Formant, and Groove settings.

<!‑‑image‑>Once a sample is encoded, there are some playback parameters to set. For example, if a sample has been looped during editing, you need to tell the VP9000 you want it to play back with that loop, and decide wh ether a sample will be monophonic or polyphonic. You might also want to change its central playback pitch and define whether it responds to incoming pitch data. The last option is ideal for fixing the pitch of drum loops that will be layered with musical samples: a rhythm loop shouldn't usually change in pitch as the musical samples are changed, so if you make it impervious to pitch data, it won't. Samples can also be set not to respond to Time, Formant and Groove parameters.

<!‑‑image‑>One of Roland's supplied demos for the VP9000 illustrates the above point quite well. It's a track featuring drums, bass and vocal, which the user can tweak in real time, changing the pitch, time and formant content of the vocal, the pitch, time and groove of the bass, and the time and groove of the drums. It seems like magic that the pitch of the drums remains the same while that of the other elements is being tweaked, but Roland have achieved this seemingly impossible trick by sampling vocals, bass and drums separately and block ing the drums' response to pitch. When you first hear the demo, you could think the entire mixed track has been sampled, and that the VP9000 is magical enough to know which sound is the drums and smart enough not to change its pitch!

<!‑‑image‑>One parameter that retains its magical feel, even with familiarity, is 'Robotize' (available only for 'Solo' encoded samples). Turn this on and pitch information in a vocal (or instrumental) sample is removed. The singer is speaking the lyric in a monotone. But now you can impose a new melody on the vocal, which retains its rhythmic feel and expressiveness. Though the sound isn't completely natural, the effect is fabulous. And it gets better: adding spot‑on harmonies or counter‑melodies to the Robotized vocal (or an un‑Robotized one, for that matter) is as simple as playing chords on an attached MIDI keyboard. With t he right playback mode setting you can even have the false harmonies join in naturally to properly echo the main vocal, as backing vocals would, in the middle of a line. Imagine the sampled line is "Old McDonald had a farm": start playing the backing chords you want the vocal to sing at "had a farm" and they sing "had a farm" too, rather than re‑triggering from the start of the line.

<!‑‑image‑>Returning to sample playback parameters, there are just a couple more to mention: fade‑in/out, which is a simple substitute for a proper envelope generator (a real EG would have been nicer), and LFO settings. The onboard LFO is well specified, offering random, chaotic, sample and hold, triangle, sine, sawtooth, square and trapezoid waveforms. Delay and speed parameters are available, and it can even be sync'd t o incoming MIDI clock. There are separate LFO depth controls for formant, pitch, pan, and level. Another nice feature is that keyboard tracking can be applied to pitch, time‑stretching, formant changes and pan position. Both the last facility and the LFO allow more expression and variety to be added to a sample as it's played.

Hands On

The pitch of samples can be fine‑tuned or assigned to track the keyboard.

The pitch of samples can be fine‑tuned or assigned to track the keyboard.

<!‑‑image‑>Despite a rather obtuse manual that waits until chapter 7 to introduce 'creating and editing waves' — sampling to anyone else — the VP9000 isn't difficult to use. The large display and good use of graphics and menus help, and it's fast in operation. Sampling with the VP is especially straightforward, at least partly becau se there's none of the multisampling and key‑mapping of conventional samplers. We used a single sample of bass guitar, cello, analogue synth, and flute, for example, over an octave and more each way, with results that equalled a good multisample.

Most people interested in the VP9000, however, will probably find freedom from multisampling a lesser part of its attraction. The real draw will be the promise of radical and transparent manipulation of essential elements of audio in real time, instant matching of loops and samples at different tempos and pitches, new melodies for sung vocals and new grooves for existing rhythms, harmonies sans vocalist, and novel and exciting audio effects. Just how well does the VP9000 fulfil its promise in these areas?

We were expecting good things in the pitch department, and for the most part we got them on monophonic, rhythmic and mixed audio, though we didn't feel the 9000 necessarily outdid by a large margin some of the dedicated software around at the moment. (The difference, of course, is that the 9000 works fluidly and spontaneously to change pitch as you turn a knob, unlike an off‑line software process.) Relatively small shifts, enough for correction, or adding a simple new pitch series varying up to seven semitones (a fifth) from the original pitch, are very convincing. However, even these shifts sound a little different from the original sample. For many users, and certainly for anyone listening to the results, this won't be a problem, as quality remains high. As pitch is shifted further from its original position the result becomes less natural, but may still be usable in some applications. (When did sounding artificial last do a dance track any harm?) Also, tweaking the Formant knob (in the case of solo samples) can keep some artifacts at bay.

The VP's time‑stretching powers are impressive. Only at fairly extreme stretches (more than a quarter faster than normal) does the 'warbling' effect of less successful processors begin creeping in, and even then it's a paler and less destructive version. Slowing a sample to half its original length causes the VP's real‑time looping (see 'The Clever Bit' box) to become clearly audible — and with the Time knob fully to the left the VP just sustains on the first sample of the audio. However, settings in between produce very usable results. And there's nothing to beat the VP9000's immediacy. It's great hearing audio speed up or slow down instantly as you tweak the Time knob, so that you can judge quickly what degree of time change you want and exactly where the quality crosses over from acceptable to a stretch too far. Note that vibrato'd vocal samples can be as much of a problem to time‑stretch with the VP9000 as with any sampler. Though it can remove pitch information, it can't remove vibrato, which still sounds silly as it gets faster or slower with the speed of the sample.

Given the popularity of groove templates in MIDI + Audio software, the VP's regrooving powers will interest many. The option works very well as far as it goes: turning the Groove knob from centre to right gives rhythmic audio progressively more 'swing', while turning it from centre to left seems to impose an increasing amount of 'lag'. Audio quality with regrooving remains good until the extremes, and regrooving works with such things as rhythm guitar as well as drums. The fact that regrooving is so quick to use is brilliant, but at present there are only four groove templates to choose from (16‑beat Swing 1 and 2, and 8‑beat Swing 1 and 2), which seems rather limited. Maybe more can be released later — we understand Roland do plan updates to the operating software of the VP. By the way, regrooving of fully mixed audio (ie. with several sounds occurring at once) is possible, too — but it didn't work that well for us.

Formant changing, however, which is only available with monophonic audio, does work well. If you're after gender‑bending, it's here, though it won't turn your kid sister into Paul Robeson! A female vocal can be given the definite feel of a male singer with a naturally high range, and a male can be made to sound like a female alto with a big voice. Perhaps not as extreme as one would like, but still pretty amazing in the right context. The effect is even good on speech. Certain Solo‑encoded instrumental samples also lend themselves to creative use of the Formant knob. One of Roland's suggestions is muting a trumpet sample in a natural way (it sounded more like a flugelhorn when we tried it!), but from this example you can imagine the potential with other instruments. Of course, you don't have to confine yourself to natural‑sounding effects: on a solo cello, for example, we used the Formant knob for fake 'filter' sweeps, which were slightly 'stepped', but still interesting. We then discovered that assigning Formant to a pitch‑bend wheel allows much smoother sweeps. The same goes for Pitch.

<!‑‑image‑>You can also have fun making a person who doesn't sing into an electronic vocalist, as a line simply spoken into the VP9000 can be made to sing. It sounds quite like a vocoder, but the words and phrasing are much clearer. Even if you're working with good, sung vocals, the ability to totally change their tune can be am azing. Likewise, if there's a bass line or guitar solo you can't manage, you could play it into the VP9000 on one note with the right rhythm and impose the desired notes with a keyboard. It takes practice and it'll never be as good as if you could really play that solo or bass line, but it serves a purpose in the studio. It might even be conceivable to take a real guitar solo from somewhere, as long as it was pure and clean in tone, 'Solo' encode it, Robotize, and then impose a new tune.

One particularly nice side‑effect of the VP's automatic stretching and pitch‑shifting is that a chunk of a full mix can be re‑pitched for use in a new track. Often, one finds a good sample of a bit of a track that's just a rhythmic pulse on one note or chord. Playing this at different pitches and with different note values produces a new riff, but with a conventional sampler these changes in pitch obviously cause changes in tempo. The sample is too slow or too fast most of the time, and the only way to get around the problem is time‑stretching repeatedly and assigning the resulting new samples to different keys. Tedious and not very RAM‑efficient. No such trouble with the VP9000: we sampled a couple of bars of bass, drums and keyboard pad playing together on one chord, looped it, and by playing it in real time at different pitches were able to create an entirely new riff, but with the feel of the original. This ability could, of course, be abused with copyright material (though we don't for a minute suggest you do that) but it's also great for reworking your own stuff. Somewhere along the same lines, a completely different sound can be given to drum loops by instant layering. Playing a loop at its original pitch and simultaneously an octave lower produces a hip, solid, chunky feel, and the timing of the two matches perfectly.

<!‑‑image‑><!‑‑image‑><h3>MIDI Matters</h3>

Roland's publicity rightly makes much of the VP9000's real‑time processing capabilities, but they don't make available as much real‑time control of that processing as they might. Three knobs (one of which swaps between two parameters) to control up to six samples isn't really enough. Add MIDI to the equation, however, and it's all change. At a basic level, samples assigned to Performance Parts played on different MIDI channels can have their Pitch, Time, Formant and Groove tweaked over MIDI with Continuous Controllers, simultaneously. You'll need a hardware MIDI controller that allows its knobs to be assigned to several MIDI channels, or a MIDI sequencer with which to record VP9000 knob movements. Fortunately, knob movements can be transmitted over MIDI, on each Performance Part's MIDI channel. Using the VP with a sequencer it's possible to reduce an entire track to total rhythmic, melodic, temporal and formant‑fluctuating chaos, then bring it smoothly back to normality — brilliant!

In addition, standard MIDI controllers such as pitch‑bend, mod wheel and aftertouch can be assigned to a variety of onboard parameters, expanding the potential for real‑time, and sequenced, control even further. A comprehensive MIDI spec is supplied, which allows even more parameters to be MIDI controlled, though wading through this document won't be easy for the novice — however, 'mixer maps' will inevitably soon become available for popular MIDI software. When used as part of a larger system, the VP9000 can be slaved to a MIDI sequencer, and samples that have their 'Tempo Sync' parameter active will lock to the tempo of incoming MIDI clock. As mentioned elsewhere, program changes can be used to switch a Performance's samples in real time, making the best of the six‑sample limit.

VP In Charge?

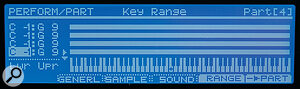

Part Performance parameters include fine control over keyboard mapping and Tempo Sync on a per‑Part basis.

Part Performance parameters include fine control over keyboard mapping and Tempo Sync on a per‑Part basis.

The VP9000 is an extremely clever and innovative processor, but a difficult one to review, because in a way it's a blank canvas until it's in the hands of users with specific needs and problems, and it's impossible to cover all the needs and problems it could address. We can certainly imagine musical situations and problems arising over the coming months that will make us wish we had a VP9000 in the studio — and remixers and creators of loop‑based music will probably see this device as a gift from the gods and well worth the money. Having had the opportunity to see what the VP9000 can do, we'd have to say that its cost is probably reasonable for the facilities it offers, but a £2300 price tag will limit access to the machine for many of the people who could make most use of it. Roland apparently have more affordable spin‑offs using the Variphrase technology already in production, so there could still be hope for the impoverished.

Outside the dance arena, too, we're certain that many other professional musicians and producers will want a VP9000 in their sonic toolbox. However, they should be aware of limitations we've already identified, notably its relatively limited multitimbrality and polyphony, and restricted single sample length (possibly the biggest annoyance for remixing). To be fair, though, a serious remixer probably has a dedicated sampler already, and would take on the VP9000 for its specific strengths.

And those strengths are many: pitch, time, formant and groove manipulation are genuinely real‑time and spontaneous, the sound quality of manipulated audio on the whole remains good, as long as you're not silly (unless you want to be silly!), loop tempo‑matching and fake harmony production are brilliant, sampling procedures are easy and quick, and it does away with multisampling. It also opens the door to no end of creative trickery which, while not impossible with previously existing technology, would be a lot slower, more difficult, and require advance planning. Even the artifacts and weird sound quality that kick in with extremes or abuse of the VP's parameters may be used creatively. If you already own a Mac or PC, £2300 will buy a lot of good sound‑processing plug‑ins. But how many of those plug‑ins offer their processes in real time? And all at once? With the VP9000, samples and tracks can go in a whole load of new directions with the spontaneous twirl of a knob.

VP9000 Brief Spec

Assigning Parts in a Performance to a keyboard range.

Assigning Parts in a Performance to a keyboard range.

- 'Real‑time' (after encoding process, that is) control over pitch, time, formant and groove.

- 6‑part multitimbral.

- 6‑voice polyphonic.

- 8Mb RAM, expandable to 136Mb.

- 1024 sample locations, 1 Performance.

- Reverb, chorus and 'multi' effect processors.

- 44.1kHz, 16‑bit sampling (8‑ or 16‑bit samples between 8kHz and 48kHz can be imported).

- 20‑bit A‑D and D‑A conversion, 24‑bit linear internal processing.

- Frequency Response: 20Hz‑20kHz.

- Analogue I/O: three balanced input jacks, six balanced output jacks, headphone socket.

- Digital I/O: co‑axial and optical S/PDIF connectors.

- 240 x 64‑dot backlit LCD.

- 250Mb Zip drive.

- SCSI: 25‑pin and full‑pitch 50‑pin connectors.

- Comes with demo Zip disk and Sound Library CD‑ROM.

Who Will Buy...?

Groove parameters can be disabled for a given sample with this software switch. If the switch is on, this screen is also where you pick the Regroove template from a current list of four possible options. However, all those currently available are of the 'four‑on‑the‑floor' variety — perhaps more complex grooves will follow in a later software update.

Groove parameters can be disabled for a given sample with this software switch. If the switch is on, this screen is also where you pick the Regroove template from a current list of four possible options. However, all those currently available are of the 'four‑on‑the‑floor' variety — perhaps more complex grooves will follow in a later software update.Remixers will probably examine the VP9000 covetously, and many of its features will be great for their needs — instant matching of loops with different tempos, for example. They'll probably require more RAM almost immediately, and will also have to bear a few other things in mind. To use the VP's powers to their fullest extent on a true remix, it is necessary to have the tracks of the original mix available for sampling (and thus tweaking) individually — drums, bass, vocals, and so on — as in the Roland demo example given in the body of this review. Other considerations include the fact that the maximum length of a sample is just 25 seconds in stereo (50 seconds mono), so even if you had all the elements of a complete track, they would have to be sampled in sections.

Remixers working with short loops, and musicians who generate tracks from scratch using multiple short loops, won't have to make quite as many compromises as remixers working with extended chunks of fully mixed audio. Whichever kind of remixer uses the VP9000, they'll have to think both vertically and horizontally: vertically because there are only six Parts in a Performance (and thus a maximum of six samples sounding at once, three if they're stereo), and horizontally because of the length limit on individual samples. Long‑form audio will need to be sampled in short sections, and in order to access more than six samples MIDI Program Changes will be necessary to switch samples.

If all this preparation and use of program changes seems to take spontaneity out of the equation, now's the time to introduce the Phrase Map. This Performance playback option organises 12 samples per Part (for a total of 72 'Phrases') onto consecutive keys of a MIDI keyboard, providing instant access to a range of drum loops, bass lines, or whatever. A track could be assembled in real time, in groovebox fashion, simply by triggering phrases from the keyboard, with a connected sequencer in 'record'. It doesn't get any easier than that!

The VP9000 could also be useful in the commercial world of broadcast and film sound. Dialogue, voice‑overs, effects beds and music could be rapidly squashed or stretched to fit specific spaces, though for these purposes an option to time‑stretch with exact values would be useful — so that a 12‑second soundbite could be instantly made to fit in 10.5 seconds, for example. This kind of application would probably make use of less extreme stretches, as there's more need to maintain the fidelity of the original audio than if you're remixing a dance track. Sound effects people could find the VP's sound‑bending potential useful, too. Really strange effects are possible if the VP's parameters are used in ways not originally intended.

What's A Formant?

You can back up to the built‑in 250Mb Zip drive, or to any connected drives via the VP9000's SCSI port.

You can back up to the built‑in 250Mb Zip drive, or to any connected drives via the VP9000's SCSI port.Formants are essentially peaks in the frequency spectrum of a voice or instrument that produce its characteristic sound — they help to make your voice sound like your voice. It's the clumsy way in which traditional sampling handles formants that causes the unnatural 'munchkinisation' of samples shifted from their normal pitch: as the fundamental pitch is shifted, so is the pitch of the formants, whereas when a real voice or instrument changes pitch this doesn't happen, since the formants for the most part remain constant. The VP9000, on the other hand, is capable of processing the pitch and formant aspects of a sample separately, allowing wide shifts of pitch without unnatural artifacts.

Variphrase Technology — SOS Editor Paul White Explains How The VP9000 Works

Roland are understandably guarded about how Variphrase technology actually works, but at a recent press launch for the product I was able to glean some useful information. Software‑based, non‑real‑time pitch‑shifting with formant correction has been available for some years now. In general it works a lot better than real‑time pitch shifting because the software can examine the file prior to processing, so the processing itself can be optimised to the type of audio being processed. By contrast, a conventional real‑time system uses a 'one size fits all' algorithm that treats the whole audio file in the same way, often resulting in non‑musical modulation and blurred or doubled transients.

Roland confirm that they employ a refinement of the traditional pitch‑shifting method, in which audio is cut into many short segments, each of which is either looped when dropping the pitch or shortened when increasing the pitch. Cross‑fading rejoins the segments as seamlessly as possible. The main difference is that the VP9000 first examines the audio and creates a 'map' of where the best splice points are, taking into account transients, repeated waveforms, and so on. In this respect, it's not unlike a non‑real‑time system. This 'map' is saved as part of the file header, but the sampled audio itself remains unprocessed. The clever part is that, during playback, the audio is processed in real time according to the instructions stored in the 'map'. In other words, the system combines the benefits of a non‑real‑time system with the immediacy of real‑time playback and sound manipulation.

<!‑‑image‑>Formant correction only applies to monophonic sounds, and if it's to work properly the audio must be genuinely monophonic and free from hum, buzz or bleed from other tracks. Guitar can be problematic due to double or overlapping notes. As far as I can tell (and I have to admit this is part speculation), the formant part of the sound is resynthesized and can be set to track the keyboard pitch or not, like the filter setting in a synth. With no tracking, the formant stays fixed, regardless of the pitch of the final note, but when chords are played, this can produce a vocoder‑like effect as the formants are too perfectly in tune. Apparently, adding some keyboard tracking to allow the formant to move slightly with pitch reduces this effect considerably.

The formant part of the process can only be approximate, because to accurately establish the formants in a real voice it would first be necessary for that voice to sing a whole range of pitches so that the algorithm could use correlation techniques to figure out what components were fixed and which were changing. Maybe this is something for the future, but right now the onus is on simplicity of operation, and with a little care on the part of the user the results can sound surprisingly natural.

In the polyphonic modes, the looping and mapping process is essentially the same, but no formant correction can be applied. Even so, drum parts can be shifted over a huge range and still sound convincing. Swing can be applied to both rhythmic and non‑rhythmic audio during playback based on a small selection of swing styles. This works by modulating the oscillator that determines the playback rate, using an LFO waveform that produces the required degree of swing. This is invisible to the user, who just has to turn a knob, but it can fall apart if an audio delay is applied, as the swing effect doesn't get delayed along with the audio.

Roland are the first to admit that Variphrase technology is in its infancy, but they're very excited about its applications in the dance market, where remixers can assemble loops and phrases from different sources, regardless of key or tempo. Even solo vocals can have their tempo determined fairly accurately by first choosing a short segment that can be looped rhythmically (maybe just one or two beats), then extrapolating the extracted tempo (an automatic process) to the rest of that audio section. They're also aware that a lot of interesting effects can be achieved by abusing the technology — pushing it to its limit so that the processing artifacts become a feature — rather as was the case with Auto‑Tune and Cher's 'Believe' single. An example of this is a voice that changes formant during playback, thus morphing from male to female. It's also possible to create a host of quasi‑vocoder‑type effects. Paul White

Effective Action

<!‑‑image‑>Three processors, covering chorus, reverb, and 'multi' effects, are on board the VP9000, though audio can of course be routed to the individual outputs un‑effected. Routing samples to effects is a matter of altering send values for the first two effects, and inserting the last into a part's signal path; the multi effect's output can also be routed to reverb and chorus, and chorus can be routed to reverb. It's worth mentioning again that the mix output of the VP9000 can be resampled, complete with effects, freeing them for re‑use.

Five types of chorus, two short delays and flanger are offered by the chorus processor, while the reverb has three rooms, three halls, a garage, a plate and a non‑linear reverb. The multi effects are rather more extensive, covering 40 treatments including EQs, resonant filters, guitar effects, sundry delays, more choruses and flangers, and several chains. Some of these offer two effects (such as overdrive‑chorus), while others combine four effects for a specific purpose — Vocal Multi and Guitar Multi, for example. Strange treatments include Phonograph and Radio Tuning.

All effects are editable in detail, with 20 parameters offered by certain reverbs, and more by some multi effects. A couple of reverb algorithms even have separate high‑ and low‑frequency delay, which allows rich, deep processing to be set up. Soundwise, the choruses are warm and full — no more than you'd expect from Roland — and reverbs, while tending to 'sameyness', offer Roland's expected quality. Overall, the effects are more than respectable and in no way disgrace a £2300 processor.

Pros

- Normal sampling pitch and time constraints all but disappear.

- Audio quality remains good and quite faithful with moderate shifts and stretches.

- Real‑time operation very impressive.

- Automatic loop tempo and pitch matching incredibly useful.

- Single‑note samples can be used without multisampling.

Cons

- Individual sample length restricted.

- Limited polyphony and multitimbrality.

- Don't expect sound quality to be absolutely transparent.

Summary

The VP9000 makes a number of breakthroughs that could greatly simplify the lives of various types of musician, remixer and producer, though its most immediate appeal is probably in dance music. It's not cheap, but represents a very significant achievement on Roland's part.