The “magic team” at Room 313. From left: Arca, Björk, the Haxan Cloak, Chris Elms.

The “magic team” at Room 313. From left: Arca, Björk, the Haxan Cloak, Chris Elms.

A unique and inspired choice of collaborators helped Björk blend powerful emotion with restless experimentation.

The history of rock & roll is littered with breakup albums, and early this year the genre received a notable addition in the form of Björk’s Vulnicura. The futuristic experimentation of 2011’s Biophilia has given way to exquisite yet stark string arrangements, written by Björk, augmented by cutting–edge electronics, again courtesy of Björk, mostly in collaboration with young electronic music artists Arca, the Haxan Cloak and Spaces. Together the music and the lyrics create a compelling journey from pre–breakup unease, to the desolation of her split with long–term partner, artist Matthew Barney, to post–breakup despair and eventual healing.

In an email interview with SOS, Björk calls Vulnicura “my most ‘psychological’ album” and “an Ingmar Bergman album”, harking back to an era when art was expected to challenge and disturb. However, while the content and approach of Vulnicura may recall times past, and the heartbreak theme itself obviously is as old as mankind, the album’s form and manner in which it was made are entirely 21st Century.

“I feel like I use different methods for every album,” explains the singer. “I quite like that, both because I think the songs should run the show and I like to be their humble servant, but mostly because I get easily bored. With Vespertine [2001] I recorded all sorts of noises around the house, very quiet ones, and I then magnified them up in Pro Tools, and created rhythms with them. It took me like three years, very enjoyable, but it was like crocheting a huge blanket with a tiny needle. Homogenic [1997] was done very differently. I asked Markus Dravs to make 100 one–bar beats that had distorted ‘Icelandic volcanic’ qualities. I would sit next to him and drum the patterns on the table. Then once I got into the studio with the songs ready I had a library of beats and put them in songs like ‘Jóga’, ‘Bachelorette’ and ‘Five Years’. I would put like beat 34 in the chorus and beat 88 in the verse, or whatever.”

“I feel like I use different methods for every album,” explains the singer. “I quite like that, both because I think the songs should run the show and I like to be their humble servant, but mostly because I get easily bored. With Vespertine [2001] I recorded all sorts of noises around the house, very quiet ones, and I then magnified them up in Pro Tools, and created rhythms with them. It took me like three years, very enjoyable, but it was like crocheting a huge blanket with a tiny needle. Homogenic [1997] was done very differently. I asked Markus Dravs to make 100 one–bar beats that had distorted ‘Icelandic volcanic’ qualities. I would sit next to him and drum the patterns on the table. Then once I got into the studio with the songs ready I had a library of beats and put them in songs like ‘Jóga’, ‘Bachelorette’ and ‘Five Years’. I would put like beat 34 in the chorus and beat 88 in the verse, or whatever.”

Minimal Tech

Much of the writing and recording of Vulnicura took place at Björk’s New York home, where she has the ultimate 21st Century studio. The total music–tech content consists of an Avid Pro Tools HD Native Thunderbolt system, Genelec 1032 monitors (“I like them a lot, they sound very creamy. But they can be deceptive, because everything sounds good in them. So you have to be a little careful.”), an M–Audio controller, a Telefunken ELAM 251 microphone and Neve 1081 mic preamp.

Björk takes a hands–on role in directing her string players, as here at Syrland Studios during the making of Vulnicura.Photo: James Merry

Björk takes a hands–on role in directing her string players, as here at Syrland Studios during the making of Vulnicura.Photo: James Merry For Chris Elms’ first string session at Sundlaugin Studio in Reykjavik, a 15–piece string section was miked very close, as shown in this photo.“Melody and emotion come first. I will then slowly work on the lyrics. I wrote most of the melodies walking outside, hiking I do that a lot. The melodies whirl in my head, and build up momentum, and then I slowly figure out what kind of shape, structure and mood they need. With this album being what I have called my most ‘psychological’ album, the lyrics were important and strings would support the kind of emotions I had to express.”

For Chris Elms’ first string session at Sundlaugin Studio in Reykjavik, a 15–piece string section was miked very close, as shown in this photo.“Melody and emotion come first. I will then slowly work on the lyrics. I wrote most of the melodies walking outside, hiking I do that a lot. The melodies whirl in my head, and build up momentum, and then I slowly figure out what kind of shape, structure and mood they need. With this album being what I have called my most ‘psychological’ album, the lyrics were important and strings would support the kind of emotions I had to express.”

Once Björk is clear on the melodies, lyrics, shape and mood of a piece, she will record, edit and comp the vocals in Pro Tools, and in the case of Vulnicura, “work on the string arrangements. I mostly work from my vocal melodies, and I then have the freedom of the computer to arrange.”

She has never really played traditional instruments very much, “which is why I was so excited about the laptop in 1999. I learned to use Sibelius in that year, and most of Vespertine was done on Sibelius — all the music boxes, harps, glockenspiels, and so on. It was the same with ‘Ambergris March’ [from Drawing Restraint 9, a soundtrack album she made in 2005 with Matthew Barney]. With the string arrangements I did on Post [1995], Homogenic and Vespertine, I gradually learned to arrange, but with Vulnicura also to transcribe and conduct when needed. I also started using Pro Tools in 1999 and kinda got hooked. I like that it isn’t on a 4/4 grid, and I can be more focused on the narration, look at the music from a film perspective, rather than as a ‘house’ club thing. But to be honest, by now you can do all things in all programs, so it is mostly about what you feel comfortable with. At the end of the day, it is about the emotion. As a singer I have also always liked the challenge of not being too hooked on gear. This maybe comes from singing through bass amps in punk bands as a teenager. If you want a certain timbre, make it with your throat!

Further string sessions took place at Syrland Studios, with a larger ensemble. For an even more intimate sound, all their instruments were miked with clip–on DPA omnis.Photo: James Merry“I don’t use samplers much. I will usually gather soundbanks for each album and will then play them in on keyboards. This applies for simpler beats in songs like ‘Venus As A Boy’ [from Debut] and ‘Cosmogony’ [from Biophilia], and so on. I play my string arrangements on the keyboard or in Sibelius, but more and more I am using Melodyne to do complex arrangements with my voice. I will then copy those arrangements over to the strings.”

Further string sessions took place at Syrland Studios, with a larger ensemble. For an even more intimate sound, all their instruments were miked with clip–on DPA omnis.Photo: James Merry“I don’t use samplers much. I will usually gather soundbanks for each album and will then play them in on keyboards. This applies for simpler beats in songs like ‘Venus As A Boy’ [from Debut] and ‘Cosmogony’ [from Biophilia], and so on. I play my string arrangements on the keyboard or in Sibelius, but more and more I am using Melodyne to do complex arrangements with my voice. I will then copy those arrangements over to the strings.”

Enter Arca

For the first two thirds of 2013, Björk worked alone with her musical material, both in New York and in Reykjavik. Given the heavy subject matter, it was a daunting task. But, she explains on her web site, “then a magic thing happened to me: as I lost one thing something else entered. Alejandro contacted me late Summer 2013 and was interested in working with me. It was perfect timing. To make beats to the songs would have taken me three years (like on Vespertine) but this enchanted Arca would visit me repeatedly and only a few months later we had a whole album!”

In our interview, Björk elaborates: “When Alejandro first came to Iceland, in October 2013, I had seven songs ready, with vocals and with Sibelius string arrangements. Because of the subject matter the structures were pretty formed. We then sat together, and he in an almost clairvoyant way programmed the beats. In the beginning I sat next to him, and would sometimes tap the basic shape of the beats on the table. Then after he had come to Iceland several times we got to know each other, and we started writing together. We co–wrote half of ‘Family’, and ‘Notget’ was very 50/50.”

Bobby Krlic aka the Haxan Cloak.

Bobby Krlic aka the Haxan Cloak. Chris Elms at London’s Strongroom Studios.Alejandro Ghersi, aka Arca, is regarded as one of the rising stars of the electronic music world. The Venezuelan, who lives in East London, has enjoyed a tremendously successful two years, programming beats for four songs on Kanye West’s Yeezus (2013) and co–producing the whole of FKA Twigs’ EP2 (2013) and part of her debut album LP1 (2014). Last November he released his first solo album, Xen, on Mute.

Chris Elms at London’s Strongroom Studios.Alejandro Ghersi, aka Arca, is regarded as one of the rising stars of the electronic music world. The Venezuelan, who lives in East London, has enjoyed a tremendously successful two years, programming beats for four songs on Kanye West’s Yeezus (2013) and co–producing the whole of FKA Twigs’ EP2 (2013) and part of her debut album LP1 (2014). Last November he released his first solo album, Xen, on Mute.

“When Björk played me the record’s songs in demo form, the strings and vocal were fully formed; the lyrics were finished and a few of the songs themselves were finished right down to their final structure. I cried like a baby first time I heard ‘Family’ and ‘Black Lake’ in their demo stages! After that we just began to unite in finding ways of solving design problems emotionally, so to speak, regarding the production. We began to do this kind of graceful dance. There was a lot of silent understanding about things, a lot of respect. Every song was different, but the tone of the actual work was childlike and fun, with us dancing and laughing to the beats. There was something really beautiful about working on a record on such a heavy subject matter with such a delicate lightness and playfulness.

“With some songs we would sit next to each other, and she might have a very precise way of solving it in mind and she would give me a prompt about the feeling. I would work from there. I might program drums, textures, pads, all based on her instructions, and we would work from there. Over time she sometimes would allow me to have more time to enter a private creative cocoon and for me to explore and experiment and propose different solutions or try different things for each song. The two exceptions were ‘Notget’, which didn’t exist as a song until I played her something I had made and she wrote her part on the basis of that, and ‘Quicksand’, in which I had very little input other than just some opinions and a very small part in the synth sound design for the keyboard part she had written.”

The Liberation Of Stems

Björk and Ghersi sometimes worked together in the same room, in New York or in Iceland, and the latter also spent time working on the material at his London home studio. Ghersi uses Ableton Live rather than Pro Tools, which meant that Björk and he had to create WAV stems and load these into each other’s sessions. According to Ghersi, this potentially cumbersome process actually worked to their advantage. “I did not find it a problem at all. It was actually quite liberating to bounce stems down now and then, because it gently forced me to commit to things. I never thought about switching to Pro Tools or another DAW. Ableton is like a limb now. I switched over to it from Fruity Loops about eight years ago, on a whim to be honest, and I immediately liked how Ableton allows for quick and intuitive sample manipulation.

This composite screen capture shows the heavily edited string recordings for ‘Stonemilker’ as they were used at the mix, with the original MIDI mock–up tracks at the top. “For samples, I first and foremost have an extensive sample library of one–shots and textures I’ve been amassing since I was 14. I have all kinds of stuff, from royalty–free packs, to sample packs cracked by Russian teens found on IRC, to one–to–one drum machine samples, to self–made samples of me just exhaling into a mic. It’s all organised in a haphazard way. My other main sound sources for keyboard performances also are in the computer, especially soft synths modelled after Korg hardware. I also play piano and guitar, and am often recording both rhythmic and tonal sounds with a mic to use as samples. When I record my vocal, feedback, etc, I manipulate these afterwards with a variety of different media, like pads and keys and things like that. I’ll also often use sounds I recorded on my iPhone, selecting the bits of the recordings that resonate with me. My entire studio at home consists of Ableton, with an Apogee I/O, Genelec monitors, a MIDI keyboard and a microphone. I don’t have any outboard whatsoever.”

This composite screen capture shows the heavily edited string recordings for ‘Stonemilker’ as they were used at the mix, with the original MIDI mock–up tracks at the top. “For samples, I first and foremost have an extensive sample library of one–shots and textures I’ve been amassing since I was 14. I have all kinds of stuff, from royalty–free packs, to sample packs cracked by Russian teens found on IRC, to one–to–one drum machine samples, to self–made samples of me just exhaling into a mic. It’s all organised in a haphazard way. My other main sound sources for keyboard performances also are in the computer, especially soft synths modelled after Korg hardware. I also play piano and guitar, and am often recording both rhythmic and tonal sounds with a mic to use as samples. When I record my vocal, feedback, etc, I manipulate these afterwards with a variety of different media, like pads and keys and things like that. I’ll also often use sounds I recorded on my iPhone, selecting the bits of the recordings that resonate with me. My entire studio at home consists of Ableton, with an Apogee I/O, Genelec monitors, a MIDI keyboard and a microphone. I don’t have any outboard whatsoever.”

Between the Autumn of 2013 and the early Spring of 2014, Björk and Ghersi programmed and reworked much of the album, with the two co–producing seven of the album’s nine tracks — Björk produced the album’s opener, ‘Stonemilker’ and its closer, ‘Quicksand’, alone. Björk was aided in her efforts by engineers Bart Migal, who assisted her in New York, mostly recording her vocals, and Frank Arthur Blöndahl Cassatta, who worked with her in Reykjavik, mostly recording strings.

Slate Digital’s Virtual Mix Rack was used extensively to help ‘warm up’ the sound of the strings.

Slate Digital’s Virtual Mix Rack was used extensively to help ‘warm up’ the sound of the strings. FabFilter’s Pro–MB multi–band plug–in was used to control the frequency excesses of Björk’s dynamic vocal performance.By the end of this period, the recordings for the songs ‘Lionsong’, ‘A History Of Touches’ and ‘Black Lake’ were complete. This meant that Björk still had barely half an album finished, and to speed things up she decided in May to contact another engineer, who could work full–time on the project until its completion at the end the year. The next seven months consisted of more recording, programming, doing additional overdubs, and an embroidery–like, prolonged, painstaking mix process.

FabFilter’s Pro–MB multi–band plug–in was used to control the frequency excesses of Björk’s dynamic vocal performance.By the end of this period, the recordings for the songs ‘Lionsong’, ‘A History Of Touches’ and ‘Black Lake’ were complete. This meant that Björk still had barely half an album finished, and to speed things up she decided in May to contact another engineer, who could work full–time on the project until its completion at the end the year. The next seven months consisted of more recording, programming, doing additional overdubs, and an embroidery–like, prolonged, painstaking mix process.

Making Preparations

The engineer who Björk contacted in May 2014 was Chris Elms. The Briton attended the BRIT School in Croydon, played guitar live for Leona Lewis and Katie Melua, and five years ago started to work as an engineer for producer Guy Sigsworth. Elms’ engineering, mixing and programming credits since then include Alison Moyet, Diana Vickers, Jessie J, Tinie Tempah and Tinchy Stryder, while two years ago, Sigsworth and Elms worked on Alanis Morissette’s Havoc And Bright Lights (see SOS October 2012 issue). Sigsworth has worked extensively with Björk, and he recommended Elms to her.

Elms recalls: “When I first arrived in New York, all the songs had been written, with the recording of some songs completed, including final strings and vocal productions, and the rest of the songs sketched out in Pro Tools, in most cases also with final vocals. A lot of the work I did from May onwards was working with Björk on preparing the strings of the unfinished songs for recording, and of course Alejandro did a lot more programming as we went along and the songs changed shape and became more and more formed. ‘Stonemilker’ was just a single keyboard track at that point with a string sound, to which Björk had sung a scratch vocal. That was the seed of that song.

“Björk and I were mocking up the strings in her computer using Native Instruments’ Kontakt with NI’s Session Strings Pro orchestral sample library. That sounded good enough for her purposes. We were using just three layers — pizzicato, tremolo and legato — and that was it. Björk has a great ear for melody, and she knew exactly what the finished result, with the real strings, was going to sound like. Although she has an M–Audio keyboard, a lot of the work she does is simply with mouse and computer keyboard.

Chris Elms used level automation extensively on Björk’s vocal performance. The greyed–out tracks were sent to a hardware LA2A compressor and recaptured to the tracks beneath them, where the heavy automation is being used to avoid sending consonants to the reverb or delay.“We took her string arrangements and split them up over the string instruments, and that went into Sibelius, in which Bjork spend time adding dynamic markers and technique markers and all that kind of stuff. I recall us spending a lot of time on a complicated arpeggiated string part for ‘Family’. I also stemmed out what we were doing from Pro Tools and sent it to Alejandro, and he’d re–edit and reprogram things in Ableton, and I’d load the WAV files he sent back into Pro Tools. But for the most part my first trip to New York involved arranging and planning the string recordings, after which we went to Iceland to record the real strings.”

Chris Elms used level automation extensively on Björk’s vocal performance. The greyed–out tracks were sent to a hardware LA2A compressor and recaptured to the tracks beneath them, where the heavy automation is being used to avoid sending consonants to the reverb or delay.“We took her string arrangements and split them up over the string instruments, and that went into Sibelius, in which Bjork spend time adding dynamic markers and technique markers and all that kind of stuff. I recall us spending a lot of time on a complicated arpeggiated string part for ‘Family’. I also stemmed out what we were doing from Pro Tools and sent it to Alejandro, and he’d re–edit and reprogram things in Ableton, and I’d load the WAV files he sent back into Pro Tools. But for the most part my first trip to New York involved arranging and planning the string recordings, after which we went to Iceland to record the real strings.”

The Magic Team

Once the strings had been recorded (see box) Björk’s thoughts turned to mixing. She didn’t go for a big name, but instead approached the up–and–coming electronic music artist Bobby Krlic. Krlic has released two experimental solo albums under the name the Haxan Cloak, and earlier in 2014 produced the Body’s I Shall Die Here and Wife’s What’s Between. Björk explains: “It was all very organic. I asked Bobby because he was the missing element. He had the talent to streamline and to come in with fresh ears for Alejandro and I. We had been struggling with the beat for the first half of ‘Family’, and it was such a natural and effortless overlap! In the tale of the making of the album, Chris was the engineer, Alejandro the co–writer and co–producer, and Bobby the mixer, but we really became a magic team and the roles started blurring. People really started putting their hearts into this. I have rarely felt so honoured, and the egos kinda just evaporated. So if Chris was better for mixing the vocals for ‘Family’, he just was.”

Most of the album was mixed by the Haxan Cloak, though on ‘Stonemilker’, the beats from his mix were married with the vocals and strings mixed by Chris Elms. This Ableton Live screen shows his treatment of the ‘melodic dots’ track.From his home studio in East London, Krlic elaborates: “Björk apparently was aware of my second album [Excavation, 2013] when it came out, and I met her when I was playing the ATP Festival in Iceland in June 2014. A couple of months later she e–mailed me asking if I was up for mixing her album. She sent me a couple of songs just to gauge my response and approach, and I started mixing these songs at my home studio in September. After I had done a number of rough mixes she came over, and we spent a few days at a nice small studio in Shoreditch in East London, called Baltic Place. We worked on ‘Lionsong’, ‘Black Lake’, ‘Mouth Mantra’ and ‘Atom Dance’.

Most of the album was mixed by the Haxan Cloak, though on ‘Stonemilker’, the beats from his mix were married with the vocals and strings mixed by Chris Elms. This Ableton Live screen shows his treatment of the ‘melodic dots’ track.From his home studio in East London, Krlic elaborates: “Björk apparently was aware of my second album [Excavation, 2013] when it came out, and I met her when I was playing the ATP Festival in Iceland in June 2014. A couple of months later she e–mailed me asking if I was up for mixing her album. She sent me a couple of songs just to gauge my response and approach, and I started mixing these songs at my home studio in September. After I had done a number of rough mixes she came over, and we spent a few days at a nice small studio in Shoreditch in East London, called Baltic Place. We worked on ‘Lionsong’, ‘Black Lake’, ‘Mouth Mantra’ and ‘Atom Dance’.

“Following this I went to Reykjavik, in October, where we worked at a studio called Room 313. Things went back and forth between us for a good four or five months, with me doing a lot of work in my home studio. Generally what happened was that I would receive stems, and I then did a lot of the mixing and also some programming at home, and I’d send that to her, and then we’d tweak things together at 313. We also worked for a few days at Strongroom Studios in London, but most of the mixing took place at 313. The entire mix process was long, and thematically it was very heavy. But with nobody in a rush, it enabled everyone to reflect on the work a little bit more.

The stem mastering session for ‘Stonemilker’, with the final master at the top, followed by Chris Elms’ mix, his treatment of the Haxan Cloak’s mix of the beats, then strings and vocals.“I had made Björk aware when she first contacted me that I would do the whole thing in Ableton, and I quickly got introduced to Chris, who was responsible for sending me stems as WAV files, which I imported in Ableton, in which I also worked at 96k. When I say stems I’m not generally referring to groups or submixes. I received every single sound they were working with individually. This meant that some sessions ran into 180 tracks. At times it was pretty complex, and this could be a big challenge!”

The stem mastering session for ‘Stonemilker’, with the final master at the top, followed by Chris Elms’ mix, his treatment of the Haxan Cloak’s mix of the beats, then strings and vocals.“I had made Björk aware when she first contacted me that I would do the whole thing in Ableton, and I quickly got introduced to Chris, who was responsible for sending me stems as WAV files, which I imported in Ableton, in which I also worked at 96k. When I say stems I’m not generally referring to groups or submixes. I received every single sound they were working with individually. This meant that some sessions ran into 180 tracks. At times it was pretty complex, and this could be a big challenge!”

The Cloak Of Darkness

Krlic’s experimental and instrumental two solo albums, The Haxan Cloak (2011) and Excavation (2013), have received glowing reviews, typically employing terms such as “dark ambient”, “doom metal”, “unsettling” and so on. Clearly, when Björk contacted him to help her complete Vulnicura her idea was not to put a bright gloss on the album’s distressed mood and gloomy subject matter, but rather to deepen and explore it even more, particularly excavating the realms of deep bass. As Elms put it, “Bobby can do amazing things with bottom end, which became a really important part of the sonic spectrum of the album.”

Krlic confirms that his work on Vulnicura did not conform to the more usual ‘just–make–it–sound–as–good–as–you–can’ mix procedure. “When Björk approached me I had mixed my own records, but never anybody else’s. So I’m not a professional mix engineer, and one of the first things I made her aware of was that my mix approach might be different than she would have been used to. Initially Björk gave me a total, full open space to work in. I had an infinite amount of freedom in what I was allowed to do. And then later on we collaborated and fine–tuned. However, because the lyrics were very raw and very direct and personal, the way in which many of the songs were mixed was guided by that, and also by what her vocal was doing. With a track like ‘Black Lake’, for example, it’s important that the vocal remains very up–front, yet still is intimate rather than overpowering.”

Like everyone else involved, Krlic stresses that the entire mix process was very much “a proper collaboration. It did not feel like the roles were heavily defined. We were working like a band, in a really nice way.”

Ghersi recalls: “The bulk of mixing was Bobby’s responsibility, and he made important and definitive decisions about the way things were sculpted and placed. The final collaborative mixdown part only happened for a few of the more tricky songs to mix, the ones with lots of shifting parts. During the last week Bobby, Bjork, Chris and I sat together, taking turns in different teams, and we tackled the details of some mixes, rather than major balance issues, between the four of us. It was like a playful tag–team kind of thing. Mixing for some of the songs ended up to be quite embroidered with lots of different kinds of sounds, and demanded lots of perspectives to figure out. So ‘solving’ them demanded some degree of collaboration between us all.”

The entire final mixing process culminated in lengthy sessions in several different studios at Room 313 at the end of the 2014. “The last 10 days or so we had like three rooms in the same building between them exchanging files and giving opinions,” says Björk. “So so fun!”

During this final phase, it was decided to go for Chris Elms’ mix of ‘Stonemilker’ as opposed to Krlic’s. The latter comments: “That song needed a sensibility in the vocals and strings to which Chris was definitely more adept.”

Elms adds: “Later on, Björk and Mandy Parnell mastered with the final mixes as well as vocal, electronics and strings stems for each song, and Björk decided to switch to Bobby’s beat stems for ‘Stonemilker’ which definitely have a different sound than my more poppy approach. This brought the track more in line with the sound of the rest of the album.”

‘Stonemilker’

Chris Elms: “I first heard this song when I met Björk in New York in May 2014, and she mentioned that it had to have a lush, big mix. I could hear that straight away, and therefore gravitated towards this song. It’s my favourite song on the album, and whenever I had free time I would work on it, to make it sound better. I come very much from the pop world, and my general approach is to get a big, lush sound in a mix. I listen to Girls Aloud by choice, and my all–time favourite album is Def Leppard’s Hysteria! It’s pop. I love the fact that you can hear that they were obsessed with every sonic element on that album. No compromises were made at all, everything is as perfect as possible. I wanted to bring the same quality of care to the mix of ‘Stonemilker’. I felt that it had to have a luxurious, 3D sound that you can immerse yourself in. I don’t think I knew at that stage that it was to become the first single.

“I did a lot of the mix at my home in Stockholm, where I have Pro Tools HD Native, Mackie 624 monitors and Bowers & Wilkins C10 hi–fi speakers. The first thing I looked at in mixing the song was the string recording. Because we had used all these DPA clip-on mics, the sound was super–close, and one of the main things I wanted to do was to bring some of the group stereo mics back into the mix, and still retain the closeness and intimacy that Björk wanted. That was the main challenge: to get things to sound big and 3D and yet also close and intimate. I then brought in the vocal, and worked a lot with just the strings and the vocal. I knew that if I could get those two to work together, getting the beats to work with them would be really easy.”

- Strings: Avid TL Space, Slate Digital VMR, VTM & VBC, Waves Renaissance EQ, Hybrid EQ, Q10, Renaissance Bass & S1, SoundToys Decapitator, Kush Audio Clariphonic, FabFilter Pro–MB, iZotope Ozone 6.

“The string session Edit window shows nine MIDI tracks at the top, followed by melody, chordal and chorus parts, all heavily edited. The MIDI mock–up tracks were not used in the final mix. They were there for reference, for me and the string players, during the recordings. The rest of the tracks are the complete string recording, which I loaded up for Björk, and she went through them and muted things and rode the volumes how she wanted them. This is why so many sections are greyed–out. She has such an acute ear. We would spend four or five days listening to all the recordings, and she’d chop and mark it up, and when it came to putting it all back together, she could remember all the best parts, and how to make a comp from that.

Alejandro ‘Arca’ Ghersi.Photo: Daniel Sannwald“I loaded the clip-on microphone comp into my final mix, and tackled any harshness and enhanced their sonic energy. I added Rhoon and Buikersloot Church reverbs from Avid’s Space plug–in. These were not really used to add reverb, but more to give them a room energy sound — I didn’t use them to add size, but to add character. I also had the Slate Digital Virtual Mix Rack on the Rhoon Church and on quite a few other string tracks. (By the way, my Pro Tools colour scheme is grouping buses are the bright green and effects buses are the light-blue cyan colour.)

Alejandro ‘Arca’ Ghersi.Photo: Daniel Sannwald“I loaded the clip-on microphone comp into my final mix, and tackled any harshness and enhanced their sonic energy. I added Rhoon and Buikersloot Church reverbs from Avid’s Space plug–in. These were not really used to add reverb, but more to give them a room energy sound — I didn’t use them to add size, but to add character. I also had the Slate Digital Virtual Mix Rack on the Rhoon Church and on quite a few other string tracks. (By the way, my Pro Tools colour scheme is grouping buses are the bright green and effects buses are the light-blue cyan colour.)

“There are six plug–ins in total on the viola clip-on mic stem, but none of them are doing much. The REQ is a high–pass at 150Hz, the VMR is taking out some harshness, and it’s automated to take down some 1.5kHz when Björk sings, so the violas don’t clash with her vocals. The Decapitator adds a bit of warmth back in, the H–EQ is doing some mid–side EQ, taking a couple of dB mid–range out, again to create space for Björk’s vocals, and the Q10 is taking out a very specific frequency with a very tight Q. After that there’s some Slate Digital Tape Machine that adds some nice energy.

“I also had many plug–ins on the other clip-on string stems, like on the cello a Kush Audio Clariphonic EQ, which is brilliant. It does some black magic — from what I can hear, parallel EQ in the high end. It’s nice for boosting high end without getting harshness. There’s also an RBass, which is automated to bring the low end out when the cellos play the root note and the drums kick in.

“The Coles room ribbon mics are very warm–sounding, but I also wanted to give them a bit more upper–end sweetness, so I added the Clariphonic EQ to that as well, plus the Virtual Mix Rack Revival, the Renaissance EQ and the SoundToys Decapitator. The Revival basically has two knobs, ‘Shimmer’ and ‘Thickness’, and I used the latter quite a lot, to add warmth without making things sound muddy, which always is the battle. The green track called ‘Room Mics’ is my bus of all my stereo room mic pairs, and it has the Slate Digital Virtual Tape Machine, VMR Neve EQ to take out some harshness, and the FabFilter Pro–MB multi-band compressor, which acts in the upper mids, but only when the strings are really going for it. VBC [Virtual Bus Compressor] is another Slate plug–in, and I’m using its Fairchild emulation for a bit of character and to hold it a bit. From the ‘Room Mics’ track, things go to the blue ‘Verb Room Main’ effects track above it, which has another Avid Space reverb, the Virtual Mix Rack and an S1 imager — wider is always better!

“The ‘Main String Bus’ track combines all the clip-on and room mics, and has several plug–ins for some tiny touch–ups and enhancements, just to bring it all together. It has the Slate VMR Revival, the Q10 parametric EQ, which takes out some harsh frequencies with automated gains, the Slate Virtual Tape Machines to warm things up, and the Ozone 6, again to get more width. The multi-band imager in the Ozone sounds great. Yes, that’s a lot of plug–ins! It’s a consequence of the luxurious string sound I wanted to achieve, in which you can hear a lot of detail. We were working with a really clean signal chain at 96k, and when it’s all in the box and at such a high resolution, I think plug–ins are great. Particularly the Slate Digital stuff really allows you to add an analogue quality. You can now achieve that analogue warmth in the digital domain.”

- Vocals: Teletronix LA2A, Waves Renaissance EQ, H–Delay, C1, FabFilter Pro–Q & Pro–MB, Slate Digital VMR, Softube RC48.

Elms: “There’s a red track at the centre of the vocal section of the mix, which is a comp of the main vocal. This is the track that was recorded in New York with the Soundfield microphone. I think the original idea was for the track to be binaural. I summed the binaural recording to mono in the middle of the track, to get more clarity and to make sure it could cut through the strings and the electronic beats. There are two grey, deactivated tracks, which are vocal sends to an outboard LA2A. These grey tracks have intense volume automation and several plug–ins, like the Renaissance EQ, which is a high–pass at 70Hz, and the FabFilter Pro–Q EQ and Pro–MB multi-band. In the grey track with the vocals for the main part of the song, the Pro–Q takes out one frequency with a tight Q, and the Pro MB takes out some root harmonics and a little bit of harshness at 2kHz, but it’s dynamically moving. The reason I used the LA2A was because Addi, the owner of Room 313, kept raving about an original 1968 LA2A which he had just bought. I ran Björk’s vocals through it just to try it out, and it really did sound good. I had been using an LA2A emulation plug before, but the real LA2A unit had such character and presence.

“The pink tracks are the LA2A returns, which go to the blue reverb tracks above. The pink tracks have extreme effect send automation, because I’m making sure that none of the reverbs or delays get any consonants sent to them. They’re only getting nice, smooth vowels. This is a trick I learned from Guy Sigsworth. It means that reverbs and delays sound much lusher and nicer, without any harshness at all. The pink chorus vocal track also has the Pro–Q, just pulling out a couple of frequencies, and the Pro–MB, which is pulling a lot of the body out of the voice and adding clarity, but the attack speed is quite slow, so it’s not so noticeable. It also has the VMR Neve, to alter the sound of the voice for certain sections.”

In contrast to the upfront string sound, Björk laughingly says of the vocals: “We definitely had a reverb journey on this album! I’ve been quite into the dry stuff with my last couple of albums, but I was up for some cream on this one.”

“The main reverb I used on Björk’s vocals was the Softube RC48 Lexicon 480 emulation,” adds Elms. “On most of the rest of the album we used a real outboard 480 that we borrowed in Iceland. I also printed a real 480 reverb in this session, but Björk later on wanted a slightly longer release, so I swapped it for the plug–in. In addition I have a Waves H–Delay on her vocals, with a Waves C1 gate. Björk doesn’t like hearing delay tails but I love the size and space of a delay on her voice. To make both of us happy I put a gate after the delay, and keyed it to the bus input. This way the delays only sounded when Bjork was singing and there would be no tails. The intense volume automation on the vocals is because I don’t really like the sound of things that are too compressed, and I wanted her vocal to sound pristine, and give you the impression of Björk singing in your ear. I was going for a really transparent sound, and all that volume automation allowed me to maintain that over the strings and the beats.”

- Beats: Ableton EQ, reverb & compression.

Elms: “Arca’s programming for this track took up about 23 audio tracks, and they tended to consist of lots of small elements. I worked with these in the mix, and applied loads of plug–ins, but none of my treatments were used, because Bobby then took Arca’s parts and mixed them and added his own beats.”

Krlic: “I did an entire mix of ‘Stonemilker’, but only the electric elements of my mix ended up in the final version. I mixed ‘Stonemilker’ like I mixed all the other tracks, which was to first organise everything in groups. With track counts between 100 to 180 tracks I needed to do that to make things more manageable! I’d then start working on Björk’s vocals, applying EQ, notches, volume automation and so on. Once I had the vocals in a good place, I’d go through the beats, and I’d get them to sit well with the vocals.

“‘Stonemilker’ needed to feel simultaneously light and heavy in the bottom. Going through Alejandro’s sounds was always a real joy, because they are so detailed, almost pointillist. Usually it was just a matter of placing them all as widescreen as possible. One of his tracks was called ‘melodic dots’ on which I had the EQ Eight, with some mid–side EQ, and Ableton’s reverb just trying to give things the space that they need to live in the song. I also had an EQ Eight on his hi–hat, and as in many cases, I use that EQ in stereo. I like to do that, because it gives a better stereo field. I might want it slightly brighter on the left, or all the right, just to get that separation, it makes you feel like you are in the room a little bit more. Sometimes I mix with headphones and it is nice to be able to identify these nuances. On the electronics group track as a whole I had two Ableton compressors, the regular one and the Glue, which is based on the SSL compressor, and again the EQ Eight, adding some high end.”

- Stem preparation: FabFilter Pro–Q 2 & Pro–MB, NI Transient Master, Slate Digital VTM.

Mastering took place at Mandy Parnell’s Black Saloon Studios in London, with only she and Björk present. As Elms already explained, he and Krlic did not only hand over a stereo master, but also vocal, strings and electronics stems for each song. It’s a process Björk and Parnell had already worked with during the mastering of the singer’s previous album Biophilia (see SOS January 2012), and it gave Björk the freedom to swap Elms’ treatment of the electronics for Krlic’s at the last moment.

Elms: “Really the mix should be credited to her, Bobby, and myself! On the screenshot of the ‘Stonemilker’ mastering session you can see the three stems at the bottom and above that my stereo mix, and at the top the final master. When I got the call from Björk saying that she wanted to use Bobby’s stem, he sent me a stereo file of it, and I wanted to make sure that it fitted with my mix of her voice and the strings. So I EQ’ed his stereo mix, using the Pro–Q 2 and the Pro–MB. I took out a specific frequency in the kick drum, and I then enhanced the transients of it with the Native Instruments’ Transient Master. I also enhanced the snare transient, and took out some upper–end distortion on the snare. The multi–band compressor softened the frequencies up a touch, and I added some warmth with the Slate Virtual Tape Machines. I sent that back to Mandy.

“Finally, on the screenshot of the ‘StoneMilker’ mastering session you can see that Mandy’s master retains all the dynamic range of my mix. It doesn’t have an extremely large dynamic range, but that was very deliberate. A large part of the sound of this album was based on Björk’s and Alejandro’s sonic ideas, which come from the electronic music genre, which has a limited dynamic range. But the songs still take you on a good dynamic journey.”

And, it can be added, on a profound journey on other levels as well.

Dry Strings

The first string recordings with Chris Elms’ involvement took place in October 2014 at Sundlaugin Studio in Reykjavik, with a 15–piece string orchestra called U Strings. The strings to ‘Notget’, ‘Atom Dance’, ‘Mouth Mantra’ and ‘Quicksand’ were recorded during those sessions. In November there was a second set of string sessions in Reykjavik, this time at Syrland Studios, with U Strings expanded to 30 players, performing the strings for ‘Stonemilker’ and ‘Family’. Another session at Syrland saw a 14–piece choir recorded for ‘Mouth Mantra’.

Elms’ main concern during these string recordings was to realise Björk’s vision of how she wanted them to sound, which became more defined as work on the album progressed. Björk explains: “It was mostly aesthetically driven. I discovered the more I got into this album that it was an ‘Ingmar Bergman’ album, which needed to stroke that nerve system of ours with a violin bow, and the closer you feel to it, the better.”

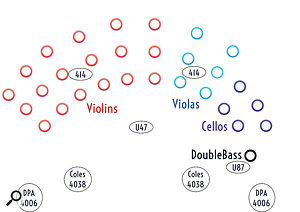

“The close–up string sound on Vulnicura is 100 percent intentional,” Elms comments. “Björk said that she wanted a warm sound with lots of presence, and that she wanted to hear the bows on the strings. She said she wanted to hear the wood. So we miked the strings a lot closer than you normally would for the first string session. But she wanted the strings to sound even closer for ‘Stonemilker’ and ‘Family’, so for the Syrland Studio sessions I opted for clip-on mics on all strings, using DPA 4099 and 4060 mics. She really liked the sound of that. She just wanted to get as close as possible.

“I thought it was a good idea to keep our options open, so I also had three pairs of room mics: a pair of DPA 4006 mics really wide out front, a pair of Coles 4038 ribbon mics just in from them and then a pair of AKG C414s in the second row of the orchestra. Plus I had a Neumann U87 close mic on the bass, and also one mono Neumann U47 in the middle, to give some additional presence to all the strings. I ran all these mics through the excellent preamps of Syrland’s Cadac console. With 30 feeds from the contact mic and the rest of the mics, we probably recorded 40 tracks at the same time, which was pretty taxing for a computer with the sessions running at 96k!

“We recorded the choir for two songs, but only one of them was used, ‘Mouth Mantra’. I had a pair of Coles 4038 mics in the room for an ambient sound, and each of the singers was holding a Shure SM58. It was the same choir that had gone on tour with Björk on her Biophilia tour, and they were used to holding SM58s.”

The Haxan Cloak

Bobby Krlic grew up in Yorkshire, learned to play the guitar, and studied Music and Visual Arts at Brighton University. “What got me into electronic music was that I did a lot of DJ’ing of rap music as a teenager, and that got me interested in how people were making beats and stuff. I found out that people were using hardware samplers, so I started off with an Akai MPC2000, and then I had an Akai Z4 sampler, and then someone told me I should get a Mac, and he gave me copies of Cubase and Reason. Particularly Reason got me into working with MIDI, audio, basic synthesis, and then during my first year at University, in 2003, I got a copy of Ableton. By that stage I’d made a lot of four–bar loops, I had a huge library of the stuff, and the amazing thing about Ableton is that you can just drop things in and fit it to the tempo. Ableton did everything I could imagine, and I’ve never looked back.

“In my studio at home I now have a laptop and an iMac with a Universal Audio Apollo interface, Event 22 monitors, and B&W CM6–S2 speakers with a PVD–1 subwoofer, one old sE Electronics condenser mic and an AKG C1000S. I also have electric and acoustic guitars, a violin and a cello, and quite a few hardware synths. I’m really into modular stuff, and have Analogue Systems Apprentice and Harvestman synths, Doepfer sequencers, and the Teenage Engineering OP1. I also just got TE’s three pocket synths in. I don’t use MIDI controllers; I tend to draw everything in by hand. I use [NI’s] Reaktor quite a bit for sampling, building a lot of stuff from scratch in there. I also like using the OP1, as well as the modular synths, which I often use to make drum sounds. I try to make my own sounds as much as I can, and all sounds that I create also are heavily processed.”

Björk’s Mics

“‘Stonemilker’ was originally called ‘Soundfield’,” reveals Chris Elms, “because Björk had used a Soundfield mic to record her vocals on top of the basic string mock-up. She had recorded the vocals for the other songs with a Telefunken 251 mic from Dreamhire in New York, which went through the Neve 1081 mic pre at her studio. Dreamhire have a vintage 251 from the 1960s which sounds great on her voice, and we wanted to buy it, so she could use it all the time, but they would not sell it. So she got the new 251E, but it did not quite sound the same. After a lot of going back and forth, in the end Telefunken and KMR Audio in London built a 251 for her according to the original ’60s spec, which sounds pretty much the same as the old one. We used her 251 when we were at Sundlaugin, when Björk wanted to redo her vocal on ‘Black Lake’. We set her up in the control room there, running the mic through the studio’s Neve 1073 mic pre.

“I also dealt with Antony Hegarty’s vocals on ‘Atom Dance’, which had been recorded before I got involved, in the Caribbean. I think they were all on holiday there, and ended up doing some recording sessions. It took quite a bit of work to get Antony’s vocals to sound right. When I asked what happened, I was told that he walked out on the beach towards the sea, and was recorded there.”