Much has changed in music recording since the first issue of Sound On Sound arrived on newsagents' shelves, a quarter of a century ago. Manufacturers and technologies have come and gone amid a series of revolutions — some of them predictable, some less so. To mark 25 years of Sound On Sound, we look back at some of the milestone products that precipitated these changes. Some are still with us and some are long gone, but all have left their indelible mark on the world of music recording.

Ableton Live (2001)

SOS review: February 2002

- "It won't replace your usual MIDI + Audio sequencer, but it might be the ideal tool for taking your studio‑bound creations out to a larger, sweatier audience.”

When it first appeared in 2001, the significance of Ableton Live wasn't immediately obvious. After all, other applications for working with loops were already well established, and in many ways, Live seemed like a refinement of the model pioneered by Sonic Foundry's Acid Pro. It was, however, a refinement with plenty of new ideas about how such a program should look and feel, embodying the principles of good interface design instead of trying to look like a 'real' mixer.

What's more, it soon became apparent that Ableton were serious in their claim that Live was designed for use, er, live. With its focus on immediacy, its ability to sync everything and anything to host tempo, and its unprecedented stability, Live has made laptop performance a reality for countless musicians. Sam Inglis

/sos/feb02/articles/ableton.asp

Akai S900 (1986)

SOS review: July 1986

- "As for overall sound quality, a 16kHz sample bandwidth is highly respectable, and the Akai is capable of a bright and cutting sound if desired.”

Once upon a time, not so long ago, the ubiquitous beige box found in every studio was not a computer but a sampler — an Akai sampler. It seems difficult now to remember how common they once were, but in the studio of the 1990s and early‑2000s the Akai S‑series was almost entirely omnipresent.

Ignoring the Akai S612 (it wasn't even the right colour), the sampler that started it all was the S900. Released in 1986 for the then enticing price of £1599, the S900 boasted an exhilarating spec list: 12‑bit sampling at rates of up to 40kHz (giving an audio bandwidth of around 16kHz), 32‑voice multisampling, cutting edge 3.5‑inch floppy disk storage (a bargain at £45 for a box of 10 at the time of our 1986 review) and eight whole notes of polyphony. A total sampling time of 63.3 seconds was possible, although only at the lowest rate of 7.5kHz. At the highest, you could expect only 11.75 seconds.

All the same, if you were a studio musician eager to sample, or perhaps thinking of forming a band called the KLF the following year, the S900 was very nearly manna from heaven. Sampling had, for the first time, reached a point where it was both practical and affordable. While the S900's historical role as progenitor of the S1000, S3000 and family is only too clear, it remains popular today with those who find its cavalier disregard for audio fidelity — or 'character' — endearing. David Glasper

Alesis ADAT (1992)

SOS review: September 1992

The Alesis ADAT recorder came hot on the heels of the two‑track DAT tape format and made digital multitrack affordable at a time when the only alternative was hugely expensive open‑reel digital hardware. Hard disk recording was in its infancy and hard drive prices were still prohibitively high, so tape was the only viable option. Announced in 1991 and shipped in 1992, ADAT used inexpensive video tape as a medium for 44.1kHz and 48kHz recordings, adopting a proprietary digital format to get eight tracks onto a VHS cassette with around 40 minutes recording time per tape. Multiple machines could be locked together to create sample‑accurate recordings of up to 128 tracks and Alesis even created a professional‑style remote controller for it — the BRC or Big Remote Control. A small remote control, or LRC, was supplied with each machine to handle basic transport functions. A welcome feature of the new ADAT digital format was that, unlike most analogue tape machines, it could produce gapless punch‑ins and punch‑outs.

While the machine was not without its frustrations (Error 7, anyone?), it was a huge technological advance and, perhaps more importantly, it gave the world the ADAT lightpipe digital interconnection format, which has become an established part of the digital audio environment. Paul White

Antares Auto‑Tune (1997)

SOS review: August 1997

- "Auto‑Tune is an exceptional piece of software that makes serious, undetectable turd polishing a reality!”

Auto‑Tune is claimed to be the best‑selling plug‑in of all time, and is undoubtedly the most controversial. It wasn't the first device that could help to put wonky vocals into perfect pitch: engineers had been using Eventide Harmonizers to do the same for years. However, this unlikely offshoot of the oil exploration industry turned what had previously been a laborious and highly skilled art into a matter of pressing a few buttons.

The consequences for the music industry have been dramatic. Whether abused as an effect, as on Cher's notorious 'Believe', or used for its intended purpose, as on almost every country record made in the last five years, Auto‑Tune has become one of very few music production tools to enter the popular consciousness. Some see it as a vital part of the engineer's toolkit, others as heralding the death of civilisation, but no‑one can deny its significance. Sam Inglis

/sos/1997_articles/aug97/autotune.html

Atari ST (1985)

Price at launch: £749 (including monochrome monitor)

Price at launch: £749 (including monochrome monitor)

By today's standards, the 1985 Atari ST computer — with its its Motorola 68000 CPU and 512 kilobytes of RAM, or a whole megabyte if you bought the fancy 1040ST version — seems laughably rudimentary. The ST range evolved somewhat throughout the '80s, not always for the better, but even the fully expanded top of the range model could only hold 4MB of memory, and if you were lucky enough to be able to afford an external hard drive, its capacity could probably be measured in tens of Megabytes, not Gigabytes. Although the Atari supported a colour display, a monochrome one was the preferred choice for music, as a higher resolution could be achieved.

What set the Atari apart from the competition was its built‑in MIDI interface. The operating system was distinctly Mac‑like, and soon some serious music sequencer software was available for it, including Steinberg's Pro 24, later evolving into Cubase, and Emagic's Creator and Notator. The ST range was later superseded by the Atari TT and Falcon computers, but a number of musicians still make music on their old Atari ST1040s, and cite its rock‑solid MIDI timing as one of the main reasons.

Whatever its strengths and weaknesses, the Atari ST was undoubtedly the catalyst for the MIDI sequencing revolution, and those early sequencers eventually evolved into the DAWs we use today. Its combination of clear graphics, a user‑friendly GUI and built‑in MIDI ports contributed greatly in pushing computer music into the mainstream. Paul White

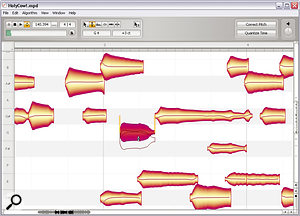

Celemony Melodyne DNA (2009)

SOS review: December 2009

- "I defy any audio engineer with a pulse to maintain 'U'‑rated language in their first response to what Melodyne Editor can do with polyphonic audio.”

The history of music technology has demonstrated time and again that it's never safe to declare anything impossible. Even so, there must be plenty of musicians out there who still need to pinch themselves every time they fire up the latest version of Celemony's revolutionary Melodyne. Other applications such as Auto‑Tune had shown that the pitch and timing of monophonic, isolated audio parts could be altered, but the idea of manipulating individual notes within chords, or isolating one instrument within a mix, still seemed like science fiction when Celemony's Direct Note Access technology was announced in 2008.

It took the company almost two years more to bring DNA to market, but despite a few teething troubles, it was immediately obvious that Celemony's claims for it were more than just hype. Melodyne DNA really can do the impossible! Sam Inglis

/sos/dec09/articles/melodynedna.htm

Digidesign Pro Tools (1991)

Price at launch: £6122 (stereo version)

Price at launch: £6122 (stereo version)

SOS review: January 1992

- "Trying to get a lowly Mac to play 16 tracks of audio through its own SCSI bus is like stuffing two dozen clowns into a Volkswagen: it might be fun to watch, but you wouldn't want to try it yourself. The secret is to use a separate processor to handle the hard disk input and output.”

The world's most widely used DAW started out as a stereo audio editing system called Sound Tools in 1989, running Sound Designer II software. However, it was two years later that the system blossomed into Pro Tools, with full multitrack recording and sophisticated DSP processing and mixing functionality. The system was quickly adopted in the music and post‑production industries, partly because of its capabilities, but also because it was considerably less expensive than the few hardware‑based alternatives at the time.

Continual development from Digidesign kept Pro Tools at the cutting edge, through innovations such as the TDM plug‑in format and clever marketing such as the 'free' native version of the system. There was a time when many users chose to run other software, such as Logic, as a front end for Digidesign hardware, but in recent years the company have made their own Pro Tools software into a formidable force. In its current form, Pro Tools HD is a hugely powerful system supporting digital formats up to 24/192 and almost unlimited track counts, with MIDI and comprehensive SMPTE support. There's also a range of affordable LE and M‑Powered versions targeted at home and semi‑pro users. Hugh Robjohns

Emu Proteus (1989)

- SOS review: November 1989

- "If the idea of samplers that can't sample seems abhorrent to you, just think of them as synthesizers that used sampled sounds instead of oscillators.”

When Marco Alpert invited me to Emu's Scotts Valley factory in early 1989 to see and hear (separately) the new product they were launching at NAMM the following week, my main worry was that it didn't sample. But as soon as I heard the sound set — not actually inside the Proteus at the time, but on an Emulator III — I realised that this was the future. I had been working hard to fit a lot of samples into a sampler's memory to allow it to be used for songwriting, but when I heard the number and quality of the sounds the Emu geniuses were squeezing into the Proteus ROM, I realised I couldn't compete... and when I saw how small and light the case was, I was sold! Then they told me it was under $1000 and I told them they would sell tens of thousands.

The number of people like me who wanted to sample was limited. Most people just wanted to get on and write music with their computer sequencer, and that is what the Proteus let you do, in a go-anywhere format. Responding on all 16 MIDI channels is the norm now, but the Proteus was the first 1U rackmount to let you do it — and who could ever imagine needing more than 32 voices? Sampler sales would take a dive and never quite recover, because the Proteus did what most people were actually using samplers for back then. Although the orchestral, world and drum sound sets that followed in subsequent Proteus products were great, they never quite captured the magic of that first sonic miracle in a single rack space. Paul Wiffen

Focusrite Liquid Channel (2004)

SOS review: July 2004

- "The crucial question is, of course, how well the Liquid Channel compares to the original units. Well, to my ears I have to say it compares extremely well indeed.”

Convolution processing to 'sample' filters and reverberant spaces is processor‑intensive, but mathematically fairly simple. As such, it's been available for a while, initially as an off‑line process in applications such as Sound Forge, and later in real time, thanks to Sony's DRE S777 rackmounting reverb.

What conventional convolution can't do, however, is replicate non‑linear processes such as distortion and compression. It fell to a company called Sintefex to figure out how dynamic processes could be emulated using more advanced convolution techniques, and Focusrite's Liquid Channel represented yet another stage in the evolution of this process. Drawing on Sintefex's expertise, they paired convolution processing with innovative analogue circuitry, capable of mimicking the response of many well‑known preamp designs, to create an input channel of unparalleled versatility. Sam Inglis

/sos/jul04/articles/focusriteliquid.htm

Fostex DMT8 (1995)

SOS review: December 1995

"Future generations of digital studio may well appear with removable media, which would be rather more practical for those working on large projects, but at the moment there's nothing else like the DMT8 at anything like the price.”

For many people, Tascam's original Portastudio and its rivals and spin‑offs were the great 'democratisers' of the recording process, but for the next generation it is surely the digital 'Portastudio' (sorry Tascam: I mean 'integrated personal multitrack recording and mixing unit') that changed the world. Roland may have dominated market share via their VS880, Yamaha may have executed the concept most elegantly in the AW4416, but Fostex got there first with the DMT8 eight‑track hard‑disk recorder/mixer.

The DMT8's on‑board 540MB drive allowed for just 12 minutes of 8‑track, 16‑bit recording, so offline data storage and backup was always a pressing issue. An optical S/PDIF connection to a DAT recorder would allow you to back up a full disk in 48 minutes, or half real‑time. The mixer was all‑analogue and typical of cassette‑based multitrackers of the time — four mic/line channels (unbalanced, therefore no phantom) with 2‑band sweep EQ, four line‑only channels, and a further eight monitor channels that could be used as extra inputs for MIDI sources on mixdown. The two aux sends could be fed from either the main or monitor channels. There was no need to lose a track to timecode to sync a MIDI sequencer, as the machine offered MIDI Clock/Song Position Pointer and MTC outputs. Basic cut and paste editing and instant locate functionality placed it ahead of analogue multitrackers in usability, but only four tracks could be recorded simultaneously. From the perspective of 2010, the DMT8 looks like one of those pioneering products that is notable more for hinting at things to come than for the reality of what it actually managed to offer. Dave Lockwood

/sos/1995_articles/dec95/fostexdmt8.html

Genelec 1031A (1991)

Price at launch: around £2500 per pair

Price at launch: around £2500 per pair

There are several good nominees for the title of classic studio monitor speaker, but if we restrict ourselves to nearfield active models the golden envelope contains but one — the Genelec 1031A. This compact, active two‑way redefined the cost‑quality equation when it was introduced in 1991, established a speaker format that remains popular to this day, and opened our ears to what a well‑designed small speaker could do.

Combining active crossover, powerful amplifiers with built‑in protection circuitry, a solidly constructed ported cabinet and Genelec's Directivity Control Waveguide, the 1031A was a formidable product. It delivered precise imaging with superb dispersion, and class‑leading levels of resolution that made it the perfect solution for near‑field reference monitoring. As a result, the 1031A (and smaller models in the same range) quickly became a standard in broadcast control rooms, OB trucks, and professional and project music studios, and countless freelance engineers acquired pairs to serve as their own transportable reference monitors.

The 1031A reigned for nearly 15 years until superseded by the 8000 series, and can still be found in many studios to this day. Hugh Robjohns

Korg M1 (1988)

SOS review: August 1988

While it was not strictly the first instrument of its kind, Korg's 1988 M1 keyboard really set the stage for today's keyboard workstations. It utilised advances in digital audio sampling to outsell its rival, the Roland D50, with more than a quarter of a million units sold, the proceeds of which apparently helped Korg buy out Yamaha's share of the company.

The M1 used either one or two digital oscillators per patch, drawn from a total of 16 oscillators, so the polyphony could be from eight to 16 voices, depending on the patches used. The rest of the signal chain was loosely based on analogue synthesizer design, with filters (no resonance, though) and envelopes, except that these were now all created digitally. Digital multi‑effects were also built-in, including the ever-useful modulation and delay treatments. The internal waveform ROM was only 4MB, tiny by today's standards, but it was still possible to coax some extraordinary sounds from this instrument, and many ended up on milestone recordings. Its piano was particularly popular, but there were also some credible drum sounds, ethnic sounds and abstract synth sounds, such as the evocative 'Lore'.

Up to eight programs could play as a Combi via key and velocity zones, while a built‑in MIDI sequencer provided up to eight tracks, though the instrument's modest polyphony meant you had to be careful about how you used this. The sequencer could even handle rudimentary editing and quantisation. Despite the fact that it offered expansion slots for memory cards, there was no floppy drive option for storage, although many third‑party products appeared to support the instrument, one of which included a floppy drive.

It was the combination of instrument and MIDI sequencer that made the M1 what it was, and many of today's workstations follow a similar paradigm, even though they are, of course, far more powerful and usually can also record audio. Paul White

Line 6 Pod (1998)

SOS review: February 1999

- "The bottom line here is that although a top engineer with a great live room, a vintage amp and a good mic or two just might get a better recorded sound, those working in more modest studios would, I think, be very hard pushed to better the Pod's endeavours.”

Next to the player, the most important factor in recorded electric guitar sounds is usually the amplifier. Yet how many home‑studio owners could dream of having a boatload of vintage Fenders, Marshalls and Voxes to choose from? And even among those lucky enough to own one of the classic amps, how many could use them to full effect without incurring a visit from Environmental Health?

Affordable digital multi‑effects units had been around since the mid‑'80s, of course, but they hadn't managed to eliminate the amplifier or loudspeaker from the signal chain, nor the need for a decent microphone. The genius of Line 6's Pod was to provide a small box that was simple to use, yet capable of simulating every part of the recording chain, from effects pedals through to the response of a miked speaker. Did it sound as good as the real thing? With hindsight, not quite. Did it feel like playing the real thing? Not really; but that is to miss the point. The Pod presented a palette of usable, recognisable guitar sounds to millions of people who would never before have had access to them. Sam Inglis

/sos/feb99/articles/line6.321.htm

Mackie CR1604 (1991)

SOS review: December 1991

- "This is a lot of mixer for the money. If it were only half as good, or twice the price, I think it might still be an attractive proposition.”

Mackie's diminutive CR1604 set a new standard for compact mixers in 1990. Sixteen channels, with three‑band EQ, feeding four outputs, might not seem like much to get excited about, but the 1604 was full of intelligent design and clever tricks. First there was the physical format — it could be rackmounted, when most mixers couldn't, or it could sit at a comfortable operating angle on a desk top, and you could rotate the connector 'pod' to form a patchbay above the control surface. The input channel Mute switches didn't actually mute at all, but routed the signal to an alternate output pairing, thereby creating a dedicated Record bus, independent of the stereo bus, allowing the latter to be used for tape return monitoring. Only the first six inputs had mic amps and only the first eight channels had insert points, doubling as direct outputs, but that was generally enough when most home recording setups were eight‑track. Four aux knobs routed to six sends, with one switchable pre/post, returning via four dedicated stereo aux returns.

Good headroom, low noise, passable EQ, all‑steel construction and high‑quality pots, switches and connectors all helped to contribute to the feeling that the 1604 was a 'pro' grade piece of kit, and it was to be seen in many a touring rack, as a keyboard submixer, for years — the latter, of course, being one application in which the 1604's idiosyncratic 60mm faders, with a centre detent, didn't seem at all odd. The delightful manual, full of helpful suggestions, ingeniously explained why a 60mm fader with unity at the halfway point was better for your mixing, but the real explanation is that Greg Mackie had a garage full of leftover graphic-EQ faders and wanted to use them up. I bought the SOS review model and for the last 12 years or so it has resided in my office at SOS, and even though I'll probably never find a use for it again, it's just too nice an object to ever think about getting rid of. Dave Lockwood

Mark Of The Unicorn 828 (2001)

SOS review: July 2001

- "The 828 is one of those 'does what it says on the tin' products that just gets on with the job without fuss.”

Ten years ago, installing a Mac or PC audio interface was not a job for the faint‑hearted. Taking your computer to bits in order to force a fragile PCI card into a recalcitrant PCI slot was only the start: you were then plunged into a nightmare world of driver installation, IRQ conflicts and control panel settings. Laptop users wanting a multi‑channel interface, meanwhile, had little choice but to invest in expensive and cumbersome external PCI chassis units.

MOTU's 828 did away with all this hassle at a stroke. Taking advantage of the then‑new Firewire protocol, aggressively promoted by Apple on their G4 PowerBooks and desktop machines, it offered the same power and flexibility as a multi‑channel PCI card in an (almost) plug‑and‑play unit, which connected via a single cable. Bliss! Sam Inglis

/sos/jul01/articles/motu828.asp

Nemesys Gigasampler (1998)

SOS review (v1.5): December 1998

- "If you need the ultimate multisampled sound that can be made only using extremely long samples, Gigasampler is probably the only way to do it.”

It seems hard now to remember a time when studios boasted racks full of hardware samplers, tied into complex webs of MIDI cables and line mixers, and there was no mileage in shipping a sample library in any format other than Akai's. Yet this was still the norm only a decade ago. With hindsight, the rise of the software sampler seems inevitable, but back in the '90s, it was a vision shared only by a few far‑sighted developers.

Software samplers offered two key advantages over their hardware counterparts. The first, close integration with other MIDI and audio editing software, was pioneered in the early '90s by Digidesign's SampleCell II system. The other was freedom from the limitations imposed by the amount of RAM installed in a system, and Gigasampler achieved its milestone status by being the first sampler to overcome this hurdle. Developers Nemesys realised that in order for the system to play back samples in a timely fashion, only the initial portion of each sample file needed to be loaded into RAM. The remainder, meanwhile, could be streamed directly from hard disk, in just the same way as any audio file is played back in a DAW.

Now a standard feature in all software samplers, this made possible a quantum leap in the realism and sound quality of sample libraries. Without disk streaming, there would be no Vienna Symphonic Library, no DFH or BFD, and no Trilogy or Stylus. Gigasampler itself lagged behind its competitors on the first point — integration with other software — and was eventually discontinued by then‑owners Tascam in 2008, but its legacy endures in the countless gigabytes of sample data residing on all of our hard drives. Sam Inglis

/sos/dec98/articles/gigasample.143.htm

Opcode Studio Vision (1990)

SOS review: February 1991

- "It's a simple, logical idea — but it's also revolutionary, and best of all, it works!”

Who created the first integrated audio and MIDI recording application? Digidesign? Steinberg? Emagic? No, Opcode, the Palo Alto‑based pioneers of MIDI sequencing on the Mac. Prior to Opcode's 1990 Studio Vision, you either locked your sequencer to tape, via SMPTE, or triggered playback of audio clips from samplers. It is, of course, a short step from inserting sample‑trigger notes in your sequence data to having the application call the audio clips directly — in fact, it's exactly the same process, other than that the integrated application can easily include graphic representations of the audio alongside the MIDI.

Opcode's Vision, one of the leading MIDI sequencer programs in 1989, was upgraded to Studio Vision by integrating it with Digidesign's Sound Tools hardware — a Nubus card‑based audio accelerator and hard disk controller. Yes, you read that right; the computers of 1990 needed DSP help just to process audio and get it on and off the drives. You couldn't do very much with the audio once it was there, other than basic editing (although the Strip Silence feature was a major innovation), and I/O was strictly limited until Digi developed multi-channel hardware, but it was clearly the future of music production and Opcode got there first. Where are they now? Bought by the Gibson guitar company in 1998, the brand and product line were terminated just a year later. Dave Lockwood

Propellerhead ReBirth RB338 (1997)

SOS review: August 1997

- "If you haven't got a computer, or a TB303/TR808 duo, you might actually come out ahead by buying a new computer and ReBirth, rather than paying the inflated prices demanded for 15‑ or 20‑year old hardware.”

The origins of software synthesis go back a surprisingly long way, and most of the plausible candidates for the title of "first software synth” actually pre‑date the launch of SOS. However, it was not until 1997 that software synthesis became a useful, practical and affordable option for everyday music production, and it was Swedish developers Propellerhead who made the breakthrough.

Dance music was at the height of its popularity, and such was the cult of Roland's TB303 Bassline that the hardware originals were fetching four‑figure sums. With perfect timing, Propellerhead offered a program that could emulate two TB303s and a TR808 drum machine for good measure. ReBirth was the first commercially important instrument that could run natively on a Mac or PC, and though long discontinued, is still remembered fondly by a generation of impecunious dance producers. Sam Inglis

/sos/1997_articles/aug97/rebirthaug97.html

Roland D50 (1987)

SOS review: May and June 1987

- "At the price the D50 is remarkable value for money. Try subtracting the cost of a digital reverb, digital echo, two chorus pedals, two eight‑note polysynths, a sampler and a couple of equalisers from the price!”

Be different. That's the secret of success. When keyboard players had enjoyed several years of wall‑to‑wall lush, 'almost in tune' analogue polysynths, followed by bright, metallic, perfectly microtuned FM, something special would be needed to get their attention. The D50 was exactly that, taking sampled attacks and blending them with synthesized sustains, a technological compromise that provided a successful and compelling alternative to analogue or FM.

Roland's inventive mix of early 'sample and synthesis' technology ticked all the boxes: rich, thick string‑synths, sounds with the characteristics of real acoustic plucked or hammered instruments, but with the advantage of familiar synthesis controls, and possibly the greatest synthesizer invention of all time: the single-note 'impress your friends' factory demo sound. In 1987, taking a Roland D50 into a studio and just holding down a key playing 'Digital Native Dance' was enough to guarantee that nothing else got done in that recording session. And this had results: listen to Michael Jackson's Bad album, Star Trek: The Next Generation theme, Jean Michel‑Jarre's Revolutions album, Enya's 'Orinoco Flow', and just about anything else from the late '80s and early '90s, and the Roland D50 will be there. Martin Russ

Sony R‑DAT format (1987)

SOS review (of the Sony DTC 1000ES): October 1987

- "Although the Sony DTC 1000ES doesn't have the programming facilities you might find on a CD player, I was able to get it to go over and over the same three‑second bit of tape. I had expected some deterioration in sound quality due to tape wear, but no — the 2000th play was as good as the first (I didn't listen to every one in between!)”

It seems strange from the perspective of 2010, with people now choosing to bounce their pristine DAW mixes via a two‑track analogue tape recorder "for the sound”, that there was a time when we couldn't wait to get rid of the damn things. The tape hiss, modulation noise, distortion, wow and flutter of analogue tape recording would soon become a distant memory as the two‑track world went digital, first via Sony's PCM F1 and 1610 video‑recorder‑based system and then, in 1987, via their R‑DAT format. 'DAT', as everyone called it (the R stood for Rotary‑head, to differentiate it from 'S'‑DAT, or Stationary‑head Digital Audio Tape formats under development by rivals) adapted the moving‑head system used by video recorders to maximise the data density on slow‑moving tape (just over 8mm/s). DAT machines recorded a two‑channel, 16‑bit signal onto a narrow‑gauge (4mm) tape cassette, at a variety of sample rates, from 48kHz down to 32kHz. Tapes of up to three hours playing time were theoretically possible, but these were horribly thin, and it was good practice to stick to 60 minutes or less, to be sure of avoiding a mishap with the complicated threading mechanism.

The copyright politics surrounding the potential for digital 'cloning' meant that DAT recorders destined for the home market were sometimes prevented from recording at the CD sample rate of 44.1kHz, and also restricted by the anti‑piracy SCMS (Serial Copy Management System). Non‑audio data within the bitstream allowed convenient index points to be recorded and edited, but adoption for home entertainment was practically non‑existent. DAT did score a big hit, however, in the professional and home‑studio markets, rapidly replacing open‑reel, quarter‑inch, two‑track machines for stereo mastering throughout the '90s, until overtaken by the widespread adoption of hard‑disk based recording systems. DAT, and particularly timecode DAT, lasted much longer in location recording for film and TV, and is only just being superseded, but ultimately history will judge the format as merely a brief interlude between the long era of analogue tape, and its ultimate successor, digital recording to hard disk and, before long, solid‑state memory. Dave Lockwood

SSL AWS900 (2004)

SOS review: November 2005

- "You can really see where the money has been spent on this console, and it constitutes a truly professional high‑end console for the mid‑market studio or post house. Throw in the perfectly executed DAW interface and console integration and this has to be my product of the year!”

The recording studio heyday of the '80s was dominated by Neve and Solid State Logic consoles — the latter introducing the in‑line console concept. However, as the big studio market started to decline 20 years later, SSL not only decided to address the needs of the well‑heeled project studio market, but also embraced the DAW as the heart of the modern studio, by offering a truly integrated console and DAW controller: the AWS900 console, launched in mid‑2004.

The AWS 900 provided up to 24 'Super Analogue' channels, each with a high‑quality mic preamp, four‑band parametric E‑ and G‑series EQ, and eight auxes. The company's full‑fat consoles always included channel dynamics but the AWS made do with two assignable mono dynamics processors, along with a G‑series bus compressor. However, a direct output was available on each channel for easy DAW interfacing, and channel insert points catered for outboard effects. The only dual‑purpose control on the channel strip was the motorised fader, switchable between the analogue console and the DAW control layer, although a user‑assignable shaft‑encoder and eight‑character display were dedicated to the DAW's corresponding channel functions.

In addition to the usual metering and monitoring facilities, the master section incorporated comprehensive transport controls and dedicated shaft‑encoders, buttons and a colour display to control the DAW's edit, mix, automation and plug‑in parameters through the HUI protocol.

In the following year, the console was augmented with Total Recall and 'AWSomation' moving‑fader automation functionality too. Priced at around £50,000, the AWS900 was hardly a budget console, but it was the most affordable from SSL and led the way in DAW/console integration. Hugh Robjohns

/sos/nov05/articles/sslaws900.htm

Steinberg VST Software Development Kit (1997)

Steinberg's long history of innovation has produced many firsts. The launch of Cubase VST in 1996 represented the first serious native alternative to Digidesign's TDM plug‑in standard. Four years later, the company began the process that would revitalise the world of synthesis and sampling, when they extended their plug‑in protocol to accommodate instruments as well as processors.

The most revolutionary aspect of the VST protocol, however, was its openness. Steinberg chose to make the VST software development kit available to anyone who chose to download it, triggering an explosion of third‑party plug‑in development and creating a vibrant on‑line community of freeware and shareware programmers. From authentic recreations of vintage processors to new and original effects, the results have had a profound effect on the world of electronic music. Sam Inglis

Tascam MSR24 (1989)

SOS review: January 1990

- "Tape recording is a well‑developed science and the limits of the possible are continually being pushed by manufacturers in all price ranges.”

From the moment Fostex launched their A8 open‑reel eight‑track in 1982, battle was joined in the narrow‑gauge multitrack war with arch‑rivals Tascam. Quarter‑inch and then half‑inch eight‑track was superseded by half‑inch 16‑track, and then one‑inch 24‑track, with Fostex's G24 taking on Tascam's MSR24. The Fostex, as always, offered a few more bells and whistles, but the Tascam was the better engineered, in my opinion, and once it offered Dolby S as an alternative to its original Dbx noise reduction in 1991 (Dolby S also featured on the Fostex), it became the better‑sounding machine, too.

The nominal spec offered a 40Hz to 20kHz (±3dB) response at 15ips, with less than 0.8 percent distortion and, with the Dolby S engaged, a 93dB signal‑to‑noise ratio. Adjacent‑channel crosstalk, unsurprisingly, was slightly less stellar, but the MSR24S was nevertheless audibly in the same league as all but the very best two‑inch machines, making uncompromised 24‑track recording no longer solely the province of the professional. Unbalanced audio connection via phonos at ‑10dBV remained as a frustrating reminder of the machine's home‑recording heritage, and a combined record/repro head made lining up a bit of a chore, but the individual channel cards and hefty remote PSU all spoke of a machine that would give service for years to come.

And then came ADAT and Tascam's own DA88 modular digital multitrack, and the market for 'semi‑pro' analogue multitrack practically died overnight. The irony is that the ADAT was actually a step backwards in terms of audio quality. The Dolby S noise reduction allowed recordings made with the MSR24 to embody all that was good about analogue tape — warm in the bass, smooth at the top end, clean in the middle and very forgiving of transients and level anomalies. It exemplifies a technology abandoned just as it achieved its peak. Dave Lockwood

TC Electronic Finalizer (1996)

SOS review: December 1996

- "If you are patient enough (and have sufficient understanding) to set up each processor section carefully, the results are nothing short of superb — but in the wrong hands, the Finalizer can wreak more havoc on your music than a second‑hand Chinese cassette in a well‑used 4‑track!”

Few products divide opinion quite as much as TC Electronic's ground‑breaking Finalizer digital mastering processor, launched in 1996. I've heard it described as "the beginning of the end — the product that started the loudness war”, yet, to me, it was an incredibly useful collection of integrated studio tools. For a while, until I replaced its functions with software, I never mixed without one. At its heart, the Finalizer is a digital multi‑band compressor and limiter, allowing the average level of a recorded mix to be raised quite dramatically before audible side‑effects are generated, whilst an integrated intelligent multi‑band expander manages internal thresholds to avoid pulling up source noise by the same amount as the internal make‑up gain.

A five‑band EQ, stereo‑width adjuster and an 'analogue warmth' feature add further tweakability, but it is the provision of presets and a Wizard requesting musical genre categorisation that, more than anything, tends to raise eyebrows amongst the sceptics. "How can an all‑in‑one digital box replace the craft and experience of a mastering engineer” they ask? Well it can't, and plenty of users have generated horrifically over‑processed home‑mastering efforts with it, helping to give the entire mastering‑box concept a bad name inside a couple of years. Used with skill and understanding, however, the Finalizer is always capable of giving you exactly the results you want, whether that is a CD‑ready, clean, polished‑sounding mix or an obviously clipped, hyped‑to‑the‑max master. I still have one, the aptly‑named Express version that has the best quick‑results interface ever designed, but like many former users these days, my favourite Finalizer presets now live on in software form. Dave Lockwood

/sos/1996_articles/dec96/tcfinalizer.html

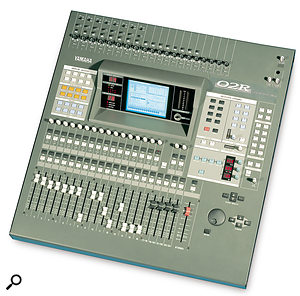

Yamaha 02R (1995)

SOS review: February 1996

- "I can't say the 02R is perfect, but its potential is immense, and we can thank Yamaha for giving the world its first virtually cable‑free professional studio that is actually affordable.”

Although the first digital studio mixer — the Neve DSP — appeared in 1980, the technology didn't become affordable and practical for the project studio market for another 15 years. However, the wait was worth it, because when Yamaha launched the original 02R in 1995, it quite literally revolutionised the industry.

Costing around £7000 on its UK launch, the 02R provided 24 analogue and 16 digital inputs, plus two stereo effects from internal SPX‑style multi‑effects engines. The eight–bus desk also offered 16 direct digital outputs, via optional interface cards.

The 02R incorporated moving faders and built‑in mix automation, plus snapshot memories for instant recall of settings, and every channel was equipped with a four‑band, fully parametric EQ, full dynamics, eight aux sends and even onboard sync delays. Importantly, the 02R introduced the assignable user interface to the project market, establishing an operational paradigm that persists in the following generations of Yamaha digital console. The 02R even enjoyed a mid‑life firmware facelift, the V2 upgrade expanding the desk's capabilities with surround sound functions, amongst many other new features. Although superseded in 2002 by the 02R96 and a whole new family of related consoles, the original 02R DNA lives on. Hugh Robjohns

/sos/1996_articles/feb96/yamaha02r.html

Honourable Mentions

To no‑one's surprise, the challenge of picking the 25 most significant products of the last 25 years provoked heated debate in the SOS office. And, inevitably, every member of the team championed a number of products that didn't quite make it onto the final list…

The RADAR from Otari (later iZ Technologies) was the first 24‑track hard disk recorder. More recently, Zoom's R16 suggested a new direction for multitrackers, recording to SD cards and boasting close integration with computer recording.

In terms of effects and processing, Aphex finally made their trademark Aural Exciter available to buy in 1985, Lexicon continued to dominate the world of reverb with their PCM‑series rackmounts, and SPL invented a new dynamics processor with their Transient Designer. Meanwhile, API's 500‑series Lunchboxes provided a novel and portable alternative to the traditional 19‑inch rack.

The cost of high‑quality microphones has tumbled in the last 15 years thanks to two factors: the explosion in Chinese manufacturing based on familiar German designs, led by the Rode NT1, and AKG's continuing work to improve electret designs, which gave us the huge‑selling C1000. Meanwhile, Rycote's superb InVision range of shockmounts made us wonder why no‑one had thought of the idea before.

Ten years ago, no serious musician who could afford a Mac would choose a Windows machine instead. Two products that helped to rehabilitate the PC were Carillon Audio's AC1, a computer in a specially designed ultra‑quiet rackmount case, and the Soundblaster Live! soundcard from Creative Labs. Music distribution was changed forever by the MP3 format developed by Fraunhofer Labs.

Significant instruments beginning with 'K' included the Kawai K5 — the first commercial additive synth — and the Kurzweil K2000, regarded by many as the gold standard of workstation synths. The resurgence of interest in analogue sounds in the '90s, meanwhile, gave us digital modelled instruments such as the Clavia Nord Lead, Access Virus, Korg Prophecy and Roland JP8000, as well as true analogue designs such as the Novation BassStation. For many, Native Instruments' B4 was the plug‑in that first convinced us that software instrument modelling could sound good.

Finally, the last couple of years have spawned several products that promise to be highly significant in years to come. Notable examples include Neumann's digital microphones, multi‑touch control surfaces such as the JazzMutant Lemur, and the spectral editing pioneered by CEDAR Audio's ReTouch.

Before Our Time

One of the things the SOS team found surprising while creating this list was the number of milestone products that, on research, turned out to be older than SOS — often by some years. This ruled out a ton of otherwise obvious candidates, among them Yamaha's DX7 synthesizer and NS10 speakers, the original TEAC Portastudio, Steinberg's Pro 24 and C‑Lab's Creator software, the Fostex A8 and R8 tape recorders, Roland's TB303 and TR909, Ensoniq's Mirage sampler and Digidesign's Sound Designer software.