Back in September 2000, this Pentium III 700MHz PC from Millennium Music was capable of running Windows 98SE, Cubase VST 3.7, quite a few plug-ins and a soft synth or two... and a similar vintage PC can still do so today.

Back in September 2000, this Pentium III 700MHz PC from Millennium Music was capable of running Windows 98SE, Cubase VST 3.7, quite a few plug-ins and a soft synth or two... and a similar vintage PC can still do so today.

Many of us feel compelled to regularly change our PCs in line with the demands of the latest software. But, depending on our requirements, an older PC may still be more than capable of doing a great job, as PC Musician discovers this month.

As the demands of software on the computers that run it become heavier and heavier, musicians can feel obliged to change their hardware every couple of years or so, which means that we often have slightly elderly PCs lying idle, despite the fact that they could well still be suitable for music making, perhaps for a friend or relative. For other musicians who haven't yet taken the plunge into running a computer studio, an old PC that can still run certain music software might be just the thing to get them into the swing. But what minimum hardware specification do you really need to run audio and MIDI software? And can you still track down older software that was written for more modest hardware in the first place? Let's find out.

Modern Audio Software Requirements

Reading the packaging for a selection of recent software releases turned up typical minimum requirements of a Pentium/Athlon XP with a clock speed of 1.4GHz and 512MB RAM. However, the recommended specs were considerably higher — typically a Pentium or Athlon XP with a 3GHz clock speed and 1GB of RAM.

This huge difference is partly because developers don't want to dissuade owners of slower PCs from buying their products, but mainly because minimum specs are generally regarded as applying to the product used in isolation — ie. what an individual soft synth might realistically need. In practice, very few people are likely to run just one piece of software like this; most will need to run some sort of sequencer, plus whatever soft synths, samplers and effect plug-ins they need to complete their songs. I'm reasonably sure that the latter is what determines the recommended specification.

Delving deeper into my chronological software pile, I soon discovered soft synths released a couple of years ago whose packaging suggested a minimum of Pentium III/Athlon 600MHz processors and 256MB of RAM, with recommended specs of an 800MHz processor and 512MB of RAM. Looking back even further, through the SOS review archives, I found that Steinberg's Wavelab 1.6 audio-editing package only needed a Pentium 133MHz processor in 1997. Of course, back in 1997 we were still excited at the prospect of being able to run a single plug-in effect, and a reverb plug-in could consume all your processing power in one gulp. Nowadays, many musicians are creating entire songs in the virtual domain and may expect to run dozens of everything. As I've said before many times in SOS, plug-ins and soft synths eat CPU for breakfast.

Second-hand PCs

Until a few years ago, PCs that were about to be thrown out were probably not fit for further active duty, but nowadays most are still perfectly usable for many general-purpose applications and even music making. If you're strapped for cash and could make good use of an elderly PC, letting friends and family know will often result in something suitable turning up. Alternatively, most towns and cities have at least one computer shop that offers low-cost 'second user' PCs with some sort of guarantee. Such shops are also a good way to find out if there are any computer clubs in your area (another good source of older computers).

If, rather than looking for an older PC, you have one that you're about to dispose of, don't just throw it into a skip. A far better solution is to donate it to a good cause. You can contact an organisation that recycles PCs (a good list in the UK can be found at www.itforcharities.co.uk/pcs.htm) or offer your hardware directly on the Donate A PC website (www.donateapc.org.uk).

Real-Time Audio & Treatment

Having said that, if you're recording acoustic/electric instruments onto audio tracks, perhaps tweaking them with a few plug-ins, with maybe some MIDI tracks outputting to a clutch of hardware MIDI synths and keyboards, your PC specification needn't be very ambitious. Many musicians build up multitrack songs primarily using audio tracks, and a typical 7200rpm hard drive can manage to record and play back 60 or 70 24-bit/96kHz tracks before running out of steam, yet still require comparatively little processing power. So those who need few plug-ins (perhaps an EQ and compressor on each of a couple of dozen tracks) could get away with an entry-level PC. It's difficult to provide an exact specification, because this depends on what combination of plug-ins you want to run, but a sensible baseline spec would be a 2001-vintage Pentium III 1GHz or equivalent machine with perhaps 512MB of RAM. I would team this with Windows XP and a couple of hard drives (one for system duties and the other dedicated to audio storage).

If you're happy to run Windows 98SE instead of Windows XP (see the 'Which Operating System' box for advice on operating systems) you could probably get away with an even older PC — I'd recommend a Pentium III 700MHz model with 256MB of RAM. You'd still be able to run a few soft synths from the same period on such a machine, but modern ones would probably struggle. However, if you wanted to add synths to your songs using a modest PC like this, sequencing external hardware MIDI synths is the way we all used to do it until a few years ago (before soft synths became so capable), and MIDI consumes very little in the way of resources, as we shall see later on.

Which Operating System?

Windows XP has proved to be by far the best Microsoft operating system to date for musicians — after all, it was the first to take multimedia performance really seriously. By comparison, Windows 98SE required far more tweaking to run audio applications successfully, although there are still plenty of musicians running this operating system, simply because once they'd finally got it tweaked to work well with audio recording/playback they were loath to abandon a smoothly-running system.

Although tweaks such as finding the most suitable Virtual Memory settings were far more critical to smooth audio recording and playback than the equivalent Paging File settings in Windows XP, Windows 98SE nevertheless remains the most suitable operating system for PCs that are slower than a Pentium II 450MHz and have less than 256MB of RAM.If you've got an older PC, it may well already be running Windows 98, and you may wonder whether it's worth upgrading to the more recent XP. I think this depends on several factors. If the PC seems to be running smoothly and the music software you propose to use is also compatible with Windows 98, perhaps it's best to leave well alone, unless you run into problems. However, do make sure you have the SE (Second Edition) version, which has better USB and Firewire implementation and multimedia performance.

Although tweaks such as finding the most suitable Virtual Memory settings were far more critical to smooth audio recording and playback than the equivalent Paging File settings in Windows XP, Windows 98SE nevertheless remains the most suitable operating system for PCs that are slower than a Pentium II 450MHz and have less than 256MB of RAM.If you've got an older PC, it may well already be running Windows 98, and you may wonder whether it's worth upgrading to the more recent XP. I think this depends on several factors. If the PC seems to be running smoothly and the music software you propose to use is also compatible with Windows 98, perhaps it's best to leave well alone, unless you run into problems. However, do make sure you have the SE (Second Edition) version, which has better USB and Firewire implementation and multimedia performance.

I also don't think it's particularly wise to install Windows XP on anything less than a Pentium II 450MHz machine or equivalent with 256MB of RAM, but if you only require a PC to record and play back audio tracks and don't need any soft synths, and either a very few or no plug-ins, you may be able to get away with a much more modest PC than this — in which case Windows 98SE is a more sensible proposition.

Another reason for sticking with Windows 98SE is if the PC in question already has a perfectly good soundcard installed, which you wish to carry on using but which doesn't have Windows XP drivers. Conversely, if you're about to buy a modern interface to partner with your old PC you may have to install Windows XP, as many manufacturers have abandoned writing Windows 98 drivers for modern audio interfaces.

A completely different approach is to use the Linux operating system, but although this is freely available (and we host a dedicated Linux Music area among the SOS Forums), not everybody has the time or the inclination to learn a completely new operating system. Nevertheless, Linux has plenty of enthusiastic followers, so I've provided several links elsewhere to SOS articles that can help get you up to speed.

Finally, the earliest MIDI sequencers for the PC were DOS (Disk Operating System) only, pre-dating the graphic interface of Microsoft's Windows altogether. Because each DOS application took over the PC rather than running alongside others, their timing could prove better than Windows sequencers, where multiple threads jockey for position. However, apart from abandoning the graphic interfaces that we're now so used to, using DOS would require a suitable pre-Windows MIDI interface and some knowledge of arcana such as I/O addresses, so DOS sequencing probably remains the domain of the enthusiast or the determined.

Audio Recording & Playback Only

Some musicians don't need to run any plug-ins or soft synths at all. For instance, there are plenty of engineers recording live performances who get the sounds right at source with careful mic positioning and therefore don't even need to use EQ plug-ins. Many classical engineers also avoid compression if at all possible. If you're only interested in recording, playing back and mixing audio tracks (using your PC like a glorified tape-recorder), a modern PC is an unnecessary luxury, and even the slower hard drives of yesteryear should manage a few dozen simultaneous tracks at 24-bit/96kHz, given a suitable audio interface.

Using Windows 98SE, I suggest a sensible baseline spec of a 1997-vintage Pentium 200MHz processor or equivalent, plus 64MB of RAM, although a 300MHz CPU would probably be a more sensible option that would enable you to run the odd few plug-ins when you needed to. If you want to install Windows XP, a 1999-vintage Pentium II 450MHz machine or equivalent with 256MB of RAM is more suitable, as XP can struggle on a lesser PC.

We're now starting to consider computers that are up to nine years old, so it's an ideal point in the proceedings to discuss another dilemma: whether to reformat their hard drives and reinstall both Windows and software from scratch, or just to leave well alone and install whatever new music software we need.

Some audio interface manufacturers, including Lynx and Echo, still offer Windows 98 drivers on their web site for older products such as the Lynx One and Mia shown here, but others don't, so always check driver availability before choosing an audio interface for an older PC.Given that PCs generally accumulate lots of software junk over the years, with an older PC it's probably sensible to at least clear this out and uninstall the applications that are no longer required. However, the uninstall routines on Windows 98-vintage PCs were notoriously bad: some left lots of detritus behind, while others were too enthusiastic and deleted shared files that were still required by other applications, so be careful. The most sensible approach is to first use an image-file utility such as Drive Image, Norton Ghost or Acronis Backup to capture an image of the current Windows partition before you start deleting stuff. Then if you later find you've disposed of something you needed after all, you won't have to panic.

Some audio interface manufacturers, including Lynx and Echo, still offer Windows 98 drivers on their web site for older products such as the Lynx One and Mia shown here, but others don't, so always check driver availability before choosing an audio interface for an older PC.Given that PCs generally accumulate lots of software junk over the years, with an older PC it's probably sensible to at least clear this out and uninstall the applications that are no longer required. However, the uninstall routines on Windows 98-vintage PCs were notoriously bad: some left lots of detritus behind, while others were too enthusiastic and deleted shared files that were still required by other applications, so be careful. The most sensible approach is to first use an image-file utility such as Drive Image, Norton Ghost or Acronis Backup to capture an image of the current Windows partition before you start deleting stuff. Then if you later find you've disposed of something you needed after all, you won't have to panic.

If you're intending to use an older PC as an audio recorder, you may be lucky enough to have one with a suitable audio interface already installed. Although today's converters do generally sound better, you could buy PCI soundcards with very decent audio quality from about 1997 onwards (my first was Echo's 20-bit Gina), and by about 2001 there were quite a few budget models capable of high-quality 24-bit/96kHz audio recording and playback. PCI soundcards predominated until about 2002, when USB 1.1 devices began to appear, and then M-Audio's Firewire 410 was one of the first budget Firewire audio interfaces to appear, in late 2003.

If, on the other hand, this is a PC donated by a non-musical friend or colleague, you may need to buy a suitable audio interface for it, and if it's running Windows 98 you'll need to get one with compatible drivers. A few older audio interfaces still being sold today have Windows 98 drivers, although it's hardly surprising that nearly all models introduced since about 2004 only support Windows XP, so bear this in mind when choosing. However, you don't need to compromise on audio quality — the excellent Lynx One soundcard (that I reviewed in SOS November 2000) still provides superb audio quality, yet has drivers available for Windows 95, 98, ME, 2000 and XP.

It will probably prove a lot easier to stick with PCI soundcard models, as there were a lot of issues with some early motherboard USB ports. Firewire support is even patchier than USB on older PCs: the first PC I bought with motherboard Firewire support was in 2003, and even today Firewire support isn't automatically included on motherboards. However, you can buy Firewire-to-PCI adaptor cards (see this month's PC Notes for a more detailed discussion on this topic) to add Firewire support, and if the adaptor card in question has Windows 98 drivers you can, of course, use it on an older PC running this operating system.

If you have an old soundcard without its Windows 98 drivers (a common situation with vintage eBay purchases), don't assume you can rely on the generic driver-download web sites (such as www.driverguide.com, www.windrivers.com, and www.driverzone.com): you'll find very few drivers there for quality soundcards and interfaces. Some audio interface manufacturers maintain archives, but not all.

All of which brings us neatly back to the reformat/leave alone debate. If you're considering reformatting the hard drive and reinstalling Windows 98SE from scratch, you should first make sure that you've either got a copy of the interface drivers, or that they are still available from the manufacturer's web site, otherwise you might find yourself in a pickle.

The Absolute Minimum-spec Music PC

When is it still worth upgrading an old PC, and when should you call it a day?

Back in 1996 I recommended a minimum of a 66MHz 486DX2 processor and 16MB of RAM to successfully run Windows 95, but soundcards at that time only supported 16-bit audio formats, while audio quality was nowhere near that of the 16-bit DAT recorders of the same period. Moreover, although the final version of Windows 95 added support for USB peripherals, there were few devices around at the time to take advantage of it.

So unless you're putting together a machine purely for the sake of nostalgia, I strongly recommend you work with Microsoft's Windows 98SE operating system, which had far more robust USB support, or the more recent Windows XP. This determines the cut-off point beyond which it simply isn't worth trying to resurrect an old PC.

In 1998, when Windows 98 was first released, Microsoft quoted a minimum spec of a 486DX 66MHz processor and 16MB of RAM, but this was extremely optimistic. A far more realistic spec, in my opinion, is any Pentium 200MHz processor or equivalent, plus 32MB of RAM. This, for me, is the minimum spec a PC needs to be at all useful to the musician.

MIDI Recording & Playback Only

If you've got a collection of hardware MIDI synths and keyboards and want to run a MIDI-only sequencer with no audio recording facilities, you can get away with a very low-spec PC. After all, a few musicians are still running Atari ST computers with an 8MHz clock speed at the heart of some complex hardware MIDI setups!

However, you have to be careful. Back in 1996, I upgraded from one version of Cubase Score, which had run happily on my the 486DX33 (33MHz) PC I was using, to one that added basic stereo audio support, and found that my PC almost ground to a halt, even when I was only using the Cubase MIDI facilities. This was because the software was optimised in a very different way to achieve smooth audio recording and playback. Later on, when Steinberg released Cubase VST 3.55, they added a 'Disable Audio Engine' feature for this reason, to suit those musicians who still relied totally on MIDI but who wanted to upgrade to the latest version of their favourite application.

So although MIDI itself takes few resources, and MIDI-only software likewise, don't assume you can use a modern MIDI + Audio sequencer on an old PC and just ignore the audio parts. The perfect solution might be to track down someone who still has an early version of your favourite sequencer with minimal audio support, or (possibly even better) an elderly MIDI-only version. It's a shame developers don't keep a few of these as freebies on their own web sites, but of course they much prefer that we buy the latest and greatest versions!

Using An Old PC Alongside A New One

If you have an elderly PC that you're about to press into service, you don't, of course, have to use it in isolation — it can instead be run alongside a newer and faster model, although you will have to keep an eye on overall acoustic noise levels in your studio. Here are some suggestions on how you could use a second computer, starting with scenarios that require a fairly powerful model and ending up with those that will suit more modest machines:

- Use it as a stand-alone soft synth PC, supporting the main music PC, connected either by MIDI, audio, or network. As discussed in the main text, the quoted minimum requirements for a soft synth tend to be what's required for the synth alone, so you can use these as a guideline to how powerful your slave PC needs to be to run a particular model. If the synths you want to run are only available as VST Instruments you'll also need a simple application to host them, such as Xlutop's Chainer (www.xlutop.com), Brainspawn's Forte (www.brainspawn.com), or Steinberg's V-Stack (www.steinberg.de). If both PCs already have a MIDI and Audio interface, the easiest way to connect the two is via a MIDI cable, or you could network them. For more information on networking music PCs, look no further than our feature in SOS August 2005 (www.soundonsound.com/sos/aug05/articles/pcmusician.htm).

- Use it as a stand-alone software sampler running an application such as Tascam's Gigastudio, Steinberg's HALion or NI's Kontakt. In this role, the emphasis tends to be more on hard drive streaming of audio rather than the performance of the CPU, so older and slower PCs will still cut the mustard as long as they have a reasonably large and fast hard drive and a reasonable amount of RAM. This is especially true if you ferry the audio back to the main PC via a network or ADAT connection to add plug-in effects, rather than doing it in situ. This approach also neatly bypasses the inevitable conflicts of attempting to run both sequencer and stand-alone software sampler on the same machine.

- Use it to safely connect to the Internet, and for word processing, accounts, downloads, and so on, connected to your main music PC via a network cable. If you don't have the main music PC powered up when you're on-line with the Internet one, there's no way any virus or other nasty can infect it, and when you're no longer on-line you can power up and transfer music updates.

- Use it as a way of storing backup files from your main PC. This approach is always safer than keeping backups on a different hard drive on the same computer, and is also an ideal scenario if you want to try Wireless (WiFi) networking, since you can then store the backup machine in another room, the garage, or even the loft, where its noise contribution won't matter. It doesn't need to be a powerful machine, either, just as long as it has enough hard drive space for your needs. The only thing to bear in mind is that, like all mechanical devices, hard drives can eventually wear out. However, fitting a new 200GB drive will cost under £50.

Software With Modest Requirements

If you're about to equip an elderly PC with music software, the obvious first port of call is musical friends who may still have old versions of their existing sequencer that they can pass on, along with any dongles and update files. I can't see that developers can grumble about this if the products in question have been long out of commercial production. There are also plenty of entry-level sequencers bundled with audio interfaces that might do the job for you.

Another approach is to look at entry-level versions of flagship sequencers such as Cubase, Sonar and so on — although, as I often remind people in the pages of SOS, even these are surprisingly powerful for the price, and therefore benefit from a reasonably fast PC. For instance, a 1.4GHz Pentium/Athlon processor and 512MB is recommended for Cakewalk's Sonar Home Studio, but you ought to be able to get away with a Pentium III 1GHz and 256MB of RAM if you don't require a lot of audio plug-ins. For Cubase SE, Steinberg recommend a Pentium/Athlon 2.8GHz machine with 512MB of RAM, but the software will run on 800MHz processors and 384MB of RAM at a push.

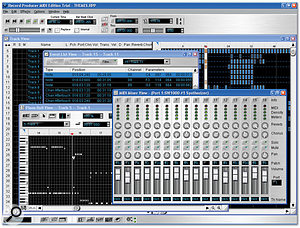

You can still buy MIDI-only software for the PC, such as Voyetra's Record Producer MIDI (shown here) which only requires a Pentium II 233MHz processor and 64MB of RAM when running under Windows 98SE.Digidesign's Pro Tools Free for Windows 98/ME runs on Pentium III-vintage machines, while some musicians have also reported success with Pentium II 300MHz machines — and, unlike the rest of the Pro Tools range, this software runs with any audio hardware. Sadly, it's no longer available at the Digidesign web site as a free download, but if you can find someone who downloaded it, it's worth getting a copy from them, since the software supports eight audio channels and 48 MIDI channels, includes EQ, compression and limiter plug-ins, and of course provides a version of the famous Pro Tools interface.

You can still buy MIDI-only software for the PC, such as Voyetra's Record Producer MIDI (shown here) which only requires a Pentium II 233MHz processor and 64MB of RAM when running under Windows 98SE.Digidesign's Pro Tools Free for Windows 98/ME runs on Pentium III-vintage machines, while some musicians have also reported success with Pentium II 300MHz machines — and, unlike the rest of the Pro Tools range, this software runs with any audio hardware. Sadly, it's no longer available at the Digidesign web site as a free download, but if you can find someone who downloaded it, it's worth getting a copy from them, since the software supports eight audio channels and 48 MIDI channels, includes EQ, compression and limiter plug-ins, and of course provides a version of the famous Pro Tools interface.

Mackie's Tracktion 2 specifies a Pentium III, 256MB of RAM and Windows 2000/XP, and has proved very popular for its ease of use and clear, single-screen interface, while Audacity (http://audacity.sourceforge.net) is a free audio editor/recorder that I reviewed in SOS July 2004. As well as being freeware, it can also run on Windows 98, ME and 2000, as well as XP. Even better, for our purposes, the minimum spec is an extremely modest 300MHz processor and 64MB of RAM. However, it doesn't support the ASIO driver format, so isn't suitable if you need low latency. Nevertheless, for those only requiring audio recording and playback, it could be just the job.

Other modest audio applications include the $45 Goldwave and $55 Multisequence (www.goldwave.com) and Tracker loop-sequencing software (which I covered in my PC Music Freeware feature — see the 'Further Reading' box). In his SOS July 2003 review of Making Waves Studio (www.makingwavesaudio.com), Mike Bryant reported that a Pentium I with 16MB RAM would suffice, yet MW Studio provides a lot of features for its £80 download price, and the MW Audio version, with simpler stereo audio but 1000 MIDI track support, costs only £20.

I also highlighted plenty of other more modest applications in my SOS April 2005 feature, 'Easier Alternatives To Flagship Music Apps' (see the 'Further Reading' box). MIDI-only software can still be bought if you search for it: For example, Voyetra's Record Producer MIDI (www.voyetra.com) supports up to 1000 MIDI tracks, SMPTE for syncing to other gear and lots of MIDI-based effects, for just $24.95. It only requires a 233MHz Pentium II processor and 64MB of RAM, or a 400MHz Pentium and 128MB RAM if running under Windows XP. So please don't take your old computer to the skip when it's been replaced by a shinier, faster model — one way or another, there's definitely life in the old dog yet!

Further Reading

- Windows 98 needs rather more tweaks than XP to make it run smoothly with audio applications. An introduction to 'Getting Started With Windows 95/98 Music Applications', including tweaking advice, can be found in SOS July 2000 (www.soundonsound.com/sos/jul00/articles/pcmusician.htm).

- Anyone interested in exploring the Linux operating system should have a look at 'Linux And Music' in SOS February 2003 (www.soundonsound.com/sos/feb03/articles/linuxaudio.asp. Further details can be found in 'Using Linux For Recording And Mastering' in SOS February 2004 (www.soundonsound.com/sos/feb04/articles/mirrorimage.htm). Possibly the easiest way to get started with Linux and music is Fervent Software's Studio To Go, reviewed in SOS May 2005 (www.soundonsound.com/sos/may05/articles/studiotogo.htm).

- If you're looking for software to suit an older PC, you should find some ideas in 'Easier Alternatives To Flagship Music Apps', from SOS April 2005 (www.soundonsound.com/sos/apr05/articles/pcmusician.htm). Other fruitful sources of surprisingly capable music applications are shareware and freeware. Take a look at our 'PC Music Shareware Roundup' from the October 2004 issue of SOS (www.soundonsound.com/sos/oct04/articles/pcmusician.htm) and the PC Music Freeware Roundup in SOS July 2004 (www.soundonsound.com/sos/jul04/articles/pcmusician.htm). These two features also include plenty of links to gateway sites that should help you track down the perfect sequencer for your needs.