Chris Watson’s fascination with location sound recording has taken him to some of the most remote places on Earth, where climatic extremes and uncooperative wildlife push his equipment and skills to their limits.

Recording sound outside the studio environment has its challenges, and veteran wildlife sound recordist Chris Watson has encountered most of them. His equipment has been frozen on polar expeditions, crushed by elephants’ feet, showered by snapping alligators, gnawed by ground squirrels and simply eaten whole by hyenas. And then there are the physical demands of dealing with extreme climates, carrying heavy equipment over unforgiving terrain and waiting patiently, day and night, for the subjects to turn up and make a noise.

“The SAS have a great saying, which is that any idiot can be uncomfortable,” say Chris, when asked how he copes with the demands of the job. “I don’t endure hardship for the sake of it, so if there is an easy route, I take it, and I do work with other people. For example, I went to Australia and Tasmania last year and my son Alex took a month off work to come and help his old dad carry stuff. So although it is very physically demanding, I am very happy to accept help from all sorts of places. I’m in my 60s now, but I still love being out there. You learn a lot about fieldcraft. You learn what you don’t need to do and about being outside.”

Bands & Bird Tables

Chris’s career as a professional sound recordist began when he joined Tyne Tees Television in 1981, but before that he was a member of the experimental band Cabaret Voltaire, which he founded in 1973 alongside Stephen Mallinder and Richard H Kirk. Even then, Chris was primarily interested in the art of recording sounds and manipulating them, having been inspired by the Musique Concrète movement and, more specifically, the work of French composer Pierre Schaeffer. For Chris, all of these activities are intrinsically linked, and they were sparked by a gift he received from his parents as a child.

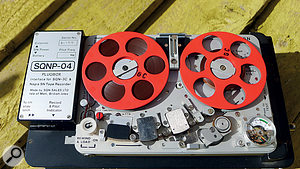

An inspired gift: the National tape recorder that launched Chris Watson on his career in sound recording.“I’ve been a sound recordist since my early teens,” he explains. “My parents bought me a National reel‑to‑reel tape recorder when I was about 12, and it’s something I still have in my studio. I can’t remember asking for it, so it was an inspired gift! It is a portable, battery‑powered device with a handle and a little microphone on a metre or so of cable. It’s designed for taking outside.

An inspired gift: the National tape recorder that launched Chris Watson on his career in sound recording.“I’ve been a sound recordist since my early teens,” he explains. “My parents bought me a National reel‑to‑reel tape recorder when I was about 12, and it’s something I still have in my studio. I can’t remember asking for it, so it was an inspired gift! It is a portable, battery‑powered device with a handle and a little microphone on a metre or so of cable. It’s designed for taking outside.

“At first I didn’t realise that it could be used outside, so I explored everything in the house. Then I remember looking out of our kitchen window in Sheffield, where I grew up, and seeing the birds on the bird table but not being able to hear them. It was like watching a silent film. I was really interested in sounds that I could see but couldn’t hear, so I ran outside with the recorder, fixed the microphone by the table and hung the recorder underneath. I put out some food then ran back inside and started recording. Fortunately the birds returned before the tape ran out, and I could see the reels going round. It was really exciting. I can remember playing those sounds back and being transported into a place that we can never be: hearing these magical time‑and‑location‑shifted sounds. I was fascinated by that.

“Later in my teens I discovered Musique Concrète and the work of composers like Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry, and realised that you could use a tape recorder not only for documenting and recording sounds, but also as a creative instrument. You could sculpt sounds with the cut and splice technique using a razor blade and edit block.

“Later in my teens I discovered Musique Concrète and the work of composers like Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry, and realised that you could use a tape recorder not only for documenting and recording sounds, but also as a creative instrument. You could sculpt sounds with the cut and splice technique using a razor blade and edit block.

“Then in the early 1970s I found a remarkable book by Terence Dwyer called Composing With Tape Recorders: Musique Concrète For Beginners, which became my handbook and Bible for working creatively with sound. It explained the techniques and what was possible: things like tape loops, speed changes, octave shifts and playing things backwards. It was so hands‑on. Unlike now with computer editing, where things either work perfectly or they don’t work at all, there’s a beautiful rough edge to tape. I’m sure I am speaking with nostalgia, but I enjoyed that physical process and contact with the material.”

Pole To Pole

Chris still uses old analogue gear on occasion because of this physical aspect and its distinctive sound. In general, though, he is thankful for the continual improvements taking place in the digital realm, with equipment becoming more reliable and more portable as technology advances.  “Things are getting much lighter, more portable and better quality. Twenty years ago I was carrying Nagra IV‑S stereo recorders around, which weigh an absolute ton. They sound fantastic, as the preamps are astonishingly good, and occasionally I still use the preamps and take the noise reduction outputs from the Nagra into a digital recorder. For example, recently I was working on a film soundtrack where the director wanted an analogue patina to the atmosphere tracks, so I processed some original digital recordings via the Nagra, recording at 15ips.

“Things are getting much lighter, more portable and better quality. Twenty years ago I was carrying Nagra IV‑S stereo recorders around, which weigh an absolute ton. They sound fantastic, as the preamps are astonishingly good, and occasionally I still use the preamps and take the noise reduction outputs from the Nagra into a digital recorder. For example, recently I was working on a film soundtrack where the director wanted an analogue patina to the atmosphere tracks, so I processed some original digital recordings via the Nagra, recording at 15ips.

“But my Sonosax SX‑R4+ recorder, which is relatively new, is incredibly lightweight and its battery consumption is minimal. This year I’ve taken it everywhere from the deserts of Saudi Arabia to the Norwegian Arctic, where it has performed better than I have in really hot and freezing temperatures. It has 16 record channels and really beautiful preamplifiers, which are almost as good as the ones on my Nagra IV‑S. But the Sonosax has DSP controls so you can configure it in all sorts of interesting ways, and it also means I don’t have to carry several kilos of batteries for the Nagra anymore.

Tools of the trade, old and new: Nagra SN and IV‑S portable reel‑to‑reel recorders have been superseded for the most part by Watson’s Sonosax SX‑R4+ digital recorder. “Since I got my Sonosax I’ve been using Inspired Energy ND2054 HD34 Rev 1.2, 49Wh 3.4Ah batteries, which are amazing. IE are an American company but the batteries are also rebadged and resold by the French company Audioroot and Sonosax themselves. The Sonosax SX‑R4+ is super conservative in terms of power consumption and it will run on one IE battery for eight or nine hours, and I’ve got half a dozen of them, so when they are charged I have roughly a week’s power.

Tools of the trade, old and new: Nagra SN and IV‑S portable reel‑to‑reel recorders have been superseded for the most part by Watson’s Sonosax SX‑R4+ digital recorder. “Since I got my Sonosax I’ve been using Inspired Energy ND2054 HD34 Rev 1.2, 49Wh 3.4Ah batteries, which are amazing. IE are an American company but the batteries are also rebadged and resold by the French company Audioroot and Sonosax themselves. The Sonosax SX‑R4+ is super conservative in terms of power consumption and it will run on one IE battery for eight or nine hours, and I’ve got half a dozen of them, so when they are charged I have roughly a week’s power.

“They have revolutionised things, because they are the size of a packet of cards, so I can take a week’s power in my hand luggage. Obviously they need to be charged, but it’s very rare that I’m away from mains power for more than a week. If I am, I’m usually with a production team who also require power, so we’ll take generators. I sometimes use a little Yamaha suitcase generator which runs on two‑stroke petrol. I was in Saudi Arabia earlier in the year looking at solar chargers, but they’re still not quite there yet. They might be all right for your phone, but not where you need to store a lot of energy. If I was on my own and away from mains for more than a week I’d probably just take more batteries.”

Space Travel

Modern technology has also made it possible for Chris to apply his interest in spatial sound, Ambisonics and aspects of surround sound to location recording. “We weren’t really able to record spatial audio on location in the past, but stereo is very 20th Century! We really should be thinking about spatial audio in all aspects of what we do, whether it is live performance, stage productions, film, radio, television or on the Web. Games certainly do. Games are at the cutting edge of spatial audio. Broadcasters are slowly being dragged into the 21st Century and are thinking about using spatial audio and surround sound in more creative ways, which is really interesting for me, because it means I can apply the techniques I have learnt over the last 10 to 15 years to broadcast.

“I think it’s getting better and better and closer to the original. That’s what spatial sound does. We are getting to the stage where you can put the listener where the microphone was when the recording was made. Games seem to be driving that spatial awareness. Virtual reality is clunky at the moment but it can only get closer to that sense of reality, whether it is a concert hall or a desert. It will draw people in. You’ll have that on your phone eventually.”

These spatial recording techniques usually involve a double Mid‑Sides array and an SQN mixer — the 5S Series II (which he has used at both the North and South Poles) is his favourite. “I’ve got a fantastically portable, really high‑quality kit, which enables me to capture spatial audio in a way that is delightful, and then work with it back in the studio. I use a SoundField 450, or a Schoeps double Mid‑Sides array, with two CCM4V cardioids and a CCM8 figure‑of‑eight, as a vertically coincident array in a Cinela suspension mount and windshield, or my self‑built Sennheiser double Mid‑Sides array. I made it from two MKH8040 cardioids and one MKH30 figure‑of‑eight, in a Rycote suspension and windshield.

Chris Watson has been interested in spatial sound for many years, but capturing surround on location is only now becoming practical. Here are three of his favoured mic setups: (above) Schoeps double M‑S array.

Chris Watson has been interested in spatial sound for many years, but capturing surround on location is only now becoming practical. Here are three of his favoured mic setups: (above) Schoeps double M‑S array. SoundField ST450 tetrahedral mic.

SoundField ST450 tetrahedral mic. Sennheiser M‑S array.“I usually prefer my Schoeps because it is small and it sings. It is a fantastic combination with the Sonosax. It’s like having a Neve preamp, where everything you put through it somehow sounds good. It is a delight to play things back through a spatial system and tune into that space. It inspires me in my work.”

Sennheiser M‑S array.“I usually prefer my Schoeps because it is small and it sings. It is a fantastic combination with the Sonosax. It’s like having a Neve preamp, where everything you put through it somehow sounds good. It is a delight to play things back through a spatial system and tune into that space. It inspires me in my work.”

Double Dare

Understandably, Chris is reluctant to lug too much equipment on expeditions to remote locations, so he takes the fewest backup components that he can get away with, banking on the reliability of modern gear to see him through. Nevertheless, very few products are resistant to teeth, as he has discovered on several occasions.

“I take spare cables and some spare microphones, and sometimes I take another recorder, but what I use is so reliable. I always carry two pairs of headphones — Beyer DT1350s and Sennheiser HD25s — but I mostly prefer the Beyers.

“It is usually the connectors and the cables that are a problem, and I have had animals eat through my cables. Hyenas in the Masai Mara not only bit through the cables, they ate them and the connectors when they got the chance.

“Similarly, I was trying to record meerkats in South Africa a couple of years ago and as I was laying the cables to leave out overnight, ground squirrels were coming out of their burrows and biting through the insulation and earthing wires, almost at my feet. The meerkats just nibbled the plastic insulation, but still damaged it, so I ended up replacing two 25 meter cables and had to laboriously bury the new ones.

“Also, several sheep ate through a lot of my long cables in the Highlands of Scotland a few years ago. I was recording a white‑tailed sea eagle, which is quite a rare bird of prey. They’re protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act of 1981, so it is a criminal offence to disturb them. I was allowed to go close to set up the microphones with somebody from the RSPB who was licensed to approach the nest during an approved visit. Then we retreated, running the cable out as we went. I had to use six or seven hundred metres of cable to get to the approved distance! The cable length possibly affected the recordings, but the choice was either that or nothing at all, so you have to use high‑output microphones, and the Sennheisers in particular have a really high output.

“I was also concerned that I wouldn’t be allowed to go back if something broke, so I used a belt‑and‑braces technique with several Sennheiser capsules. I ran one down as a single cable and two in a stereo multicore. It worked fine for several weeks, until one morning when, instead of hearing eagles, I found myself listening to the English Service of Radio Moscow, because sheep had bitten the cable and it was acting like an aerial! But the others survived, probably because the grass had grown over them.

Long cable runs are often necessary in order for Chris to be able to place mics where he needs to!“I try to hire cable on location because it’s probably the heaviest component that I use these days, but sometimes I have no choice but to take it. My SoundField microphone uses a very particular 16‑channel multicore cable, so I take that, and Schoeps do this fantastic super‑thin, lightweight, seven‑pin, three‑channel cable that I try to take with me. But for longer runs, I hire it when I am there, and these days you can get it in most places.

Long cable runs are often necessary in order for Chris to be able to place mics where he needs to!“I try to hire cable on location because it’s probably the heaviest component that I use these days, but sometimes I have no choice but to take it. My SoundField microphone uses a very particular 16‑channel multicore cable, so I take that, and Schoeps do this fantastic super‑thin, lightweight, seven‑pin, three‑channel cable that I try to take with me. But for longer runs, I hire it when I am there, and these days you can get it in most places.

“I normally end up taking three big silver flightcases and two 1550 Peli cases. Pelican and Peli are the two main companies that make very robust, high‑resilience, lightweight cases, with lots of high‑density foam inside, so camera people and sound recordists use them a lot.”

Cable Ties

Using long runs of cable between microphone and recorder isn’t just a necessity when recording wildlife from afar; it is also key to a recording philosophy Chris has come to strongly favour in recent years.

Although it sees less use these days, the parabolic reflector is a traditional tool for focussing a microphone on a distant sound source.“Years ago, it was a battle against the elements and background noise, and I struggled with that. I had this purist approach, focussing on isolating sounds using very directional microphones, parabolic reflectors and filters. Then slowly I started to appreciate those sounds around the ones I was trying to record, and that developed along with my interest in spatial sound, so now I record far less than I used to, and only when the time and sound is right.

Although it sees less use these days, the parabolic reflector is a traditional tool for focussing a microphone on a distant sound source.“Years ago, it was a battle against the elements and background noise, and I struggled with that. I had this purist approach, focussing on isolating sounds using very directional microphones, parabolic reflectors and filters. Then slowly I started to appreciate those sounds around the ones I was trying to record, and that developed along with my interest in spatial sound, so now I record far less than I used to, and only when the time and sound is right.

“Of course I still use windshields and I love my Cinela and Rycote windshields, but I also try to position microphones closer. I use fewer directional microphones now, and I tend to use longer cables. It is quite usual for me to use 100 or 200 metres of cable, and put mics in places that I think might be interesting. It helps improve the signal‑to‑ambient‑noise ratio and, on a simple level, it helps overcome mechanical sounds.

“I was recording insects in the Surrey hills this summer, and the grasshoppers and crickets were really going off the scale in the middle of the afternoon, but in a nearby field there was somebody cutting hay, so I got the microphones super close to the area where the insects were and used 100 metres of cable. When the mics are that close you can turn the recording gain down to the point where background noise just goes into infinity and you can’t hear it.

“So rather than use directional microphones and reflectors and pointing at things that were far away and getting frustrated with the background noise, I used that simple technique. Our brains can filter out these noise pollutant sounds to a degree, but a microphone can’t discriminate in that way. Hearing spatial sound from a close perspective, particularly with the Schoeps double M‑S array, and listening back in my small studio space is fantastically engaging.

“So I started off using directional mics like Sennheiser 805s, 815s, 816s, 70s, and things like that, but these days I enjoy the challenge of getting microphones close and recording better sound. There is a clarity and bottom end, which you don’t hear with gun microphones.”

Careful With That Mic...

Chris Watson also makes extensive use of tiny lavalier microphones such as the Sanken COS11 and DPA 4060 when making field recordings. “They are designed for putting on people,” admits Chris, “but there are more interesting places to put those microphones than on people! Their small size enables you to get them into places a conventional microphone wouldn’t fit, or where you wouldn’t want to put your ears. So I’ve made recordings using them inside zebra carcasses, dung beetles’ nests and things like that, using long cables.”

Not only is the diminutive size of lavalier microphones useful to Chris when recording in certain situations; so too is their ability to function in damp and dusty environments and at extreme temperatures.

Recording elephants on location. Chris’s DPA lavalier mics turned out to be robust enough to survive being trodden on!“The DPAs are designed to go on dancers and performers where they get covered in perspiration and make‑up, so they are really good in tropical rainforests where there’s a lot of humidity. And because they’re omnis, they are less susceptible to wind and handling noise. You need to insulate them a little bit from wind and weather, but they are remarkably robust.

Recording elephants on location. Chris’s DPA lavalier mics turned out to be robust enough to survive being trodden on!“The DPAs are designed to go on dancers and performers where they get covered in perspiration and make‑up, so they are really good in tropical rainforests where there’s a lot of humidity. And because they’re omnis, they are less susceptible to wind and handling noise. You need to insulate them a little bit from wind and weather, but they are remarkably robust.

“A few years ago I was recording elephants in Zimbabwe. It was very dry, so the elephants were trying to find these underground water holes, called seeps, that were under these sand banks. The elephants sniff them out, punch a hole in the sand banks with their trunks and withdraw the water. You get this wonderful phasing quality as the water moves through their trunks. It’s not a good idea to get close to wild elephants, so before they arrived, I buried some microphones, including a DPA 4060, close by the top of the sand bank. Then I ran about 100 metres of cable to a preamp, so we could listen in close up when the elephants came.

Splashing water is another hazard for the aspiring wildlife recordist.“The lead female of the group didn’t use the seep I was hoping she would, and walked over to where this DPA 4060 was and stood on it. I got this amazing crushing sound recording of everything going off as the mic was pushed into the sand. Then she moved off and stood away. But within about 10 seconds, the 4060 came back to life and was perfectly fine.

Splashing water is another hazard for the aspiring wildlife recordist.“The lead female of the group didn’t use the seep I was hoping she would, and walked over to where this DPA 4060 was and stood on it. I got this amazing crushing sound recording of everything going off as the mic was pushed into the sand. Then she moved off and stood away. But within about 10 seconds, the 4060 came back to life and was perfectly fine.

“I don’t know about immersing them in water, though. I use hydrophones if I am doing that: I’ve recorded frogs and amphibians with the DPAs on the surface of the water, but not actually underneath. And I’ve recorded snapping alligators in the Everglades, where they got splashed. Normally they’re protected by a fluffy Rycote windshield.”

Cold Snaps

As for extremes of temperature, Chris insists that in those conditions he usually stops working before his equipment does. “I am amazed how tolerant stuff is. Hot conditions are pretty bad, but cold conditions are probably more serious.

Extreme temperatures can cause equipment to fail in unexpected ways.“When I was in the Antarctic working on Frozen Planet it got down to about minus 40 on the ice fields near the Beardmore Glacier, where Lawrence Oates famously walked out of his tent. We landed there in a helicopter with David Attenborough to do some filming. I was using oxygen‑free copper cable, with irradiated plastic outer sheath, which means that it is more flexible at lower temperatures, but the best cable to use in those circumstances is rubber cable from Belden, which is super heavy and expensive, and that wasn’t available to me. I was using Van Damme cable, which is my favourite microphone cable, but it was minus 40 when I was connecting to the camera, and when I moved the cable it snapped like a piece of toffee. I had several spares and spent time repairing stuff when we got back to the base, but that was the hardest thing.

Extreme temperatures can cause equipment to fail in unexpected ways.“When I was in the Antarctic working on Frozen Planet it got down to about minus 40 on the ice fields near the Beardmore Glacier, where Lawrence Oates famously walked out of his tent. We landed there in a helicopter with David Attenborough to do some filming. I was using oxygen‑free copper cable, with irradiated plastic outer sheath, which means that it is more flexible at lower temperatures, but the best cable to use in those circumstances is rubber cable from Belden, which is super heavy and expensive, and that wasn’t available to me. I was using Van Damme cable, which is my favourite microphone cable, but it was minus 40 when I was connecting to the camera, and when I moved the cable it snapped like a piece of toffee. I had several spares and spent time repairing stuff when we got back to the base, but that was the hardest thing.

“Also we did a piece at the Amundsen‑Scott South Pole Station with David Attenborough. It is quite difficult to work there, because you can’t have any exposed skin and you have mittens on top of gloves. We stood outside for about 40 minutes and when David started a piece to camera his voice sounded really brittle. David’s voice is usually so recognisable, but it didn’t sound like him.

“I didn’t know what it was, because I was using a radio link, but then I suddenly thought that it might be the Sanken COS11 capsule. So I swapped it for a spare and it was fine. After that I swapped capsules every 20 minutes or so before they could freeze up, and I kept the spares warm inside my jacket. So I learned a lesson.

“I normally use the Sankens for speech because they have a very natural quality which some small omnis don’t, but I think all the other capsules would have frozen too. If I am not recording speech, I prefer the DPA 4060s. All of them are robust, but the DPA 4060s are probably the most robust.

“I’ve also had occasions when microphones have been eaten by hyenas, so there are elements of risk, but if you want to get a decent recording and not put yourself in jeopardy, then you have to put your microphone in jeopardy. Even in this country, if you put microphones around a badger sett, you find that they are very sensitive to human scent, so you have to smear the windshields with cow dung, which masks our scent and is something they are used to.”

When Chris is working with a film crew, his audio is synchronised to the camera so that it can be matched up correctly in the editing suite. “When shooting sync I usually ‘jam sync’ time‑of‑day timecode on my Sonosax to the camera via a cable with a five‑pin Lemo connector. We then check the sync every couple of hours. Occasionally I take Record Run timecode on the camera via a radio link.”

Bringing It All Back Home

Once the recordings have been safely captured, Chris insists that he often does as little as possible when it comes to preparing and providing audio files and notes. “Sometimes I’m the hired hand, so I just let the production team copy my SD card and that’s it,” he explains.

Chris Watson’s home studio, where he enjoys using a modular synth for creative post‑production.On other projects, however, he embarks on extensive post‑processing, for which he usually uses his home studio, based around an RME Multiface interface and Apple Mac running Steinberg Nuendo 8. For sound design work, Chris prefers to use his Eurorack‑format hardware modules rather than software. These are housed in a rack system built for him by Finlay Shakespeare of Future Sound Systems.

Chris Watson’s home studio, where he enjoys using a modular synth for creative post‑production.On other projects, however, he embarks on extensive post‑processing, for which he usually uses his home studio, based around an RME Multiface interface and Apple Mac running Steinberg Nuendo 8. For sound design work, Chris prefers to use his Eurorack‑format hardware modules rather than software. These are housed in a rack system built for him by Finlay Shakespeare of Future Sound Systems.

“I like using my original sounds as a source to process, but I really like what some of the hardware synthesizers and processors can do to those harmonically rich location sounds, so I’ve got analogue synthesizer modules from Vermona, Mutable Instruments, Expert Sleepers and 2hp. I much prefer to use hardware with hands‑on control than fiddling about with software plug‑ins. I also use hardware Lexicon PCM96 [reverbs], which I really like for altering acoustics.”

This has been something of a growth area for Chris in recent years, as he is being asked to work on documentaries and dramas that are not necessarily anything to do with natural history. “They like my work and want me to work on the sound design for their film or series,” he explains. “I’ve just been asked about working on a new BBC series by its producer, who wanted to know what I could bring to the series, because they want a particular style. I really like doing that kind of thing. So I’ll make the recordings then work in post‑production on the sound design.

“I’ve also just finished a contemporary film called Hellhole, which is set in Brussels. The director, Bas Devos, wanted the soundtrack to be the sounds of the city, rather than music. So I made several trips to Brussels to record its sounds, then I worked creatively with those sounds to compose parts of the soundtrack.

“It comprised both editing and processing, which takes me back to the work of Pierre Schaeffer that inspired me originally, and tracks like ‘Etude Aux Chemins De Fer’, where he was recording sounds in the Paris railway station in 1948.

“One of the pieces this film has is a very slow‑moving shot, which starts looking directly at the corner of a building, then moves to the next, so there is a transition. I have been taking the sounds of those spaces and morphing them from one side of the building to the other using different processing tools. So the reality of the space becomes blurred in the middle then drifts across to the different reality of the other corner, so there’s a lot of acoustic processing.

“I’ve always blurred the margins between music and sound recording because to me the two are linked. I don’t disconnect myself from it. I am part of that process, really.”

Less Is More

Over the years, Chris has had time to reflect on the quality and quantity of his work, and nowadays chooses to record far less material than he once did. “I am very careful about pressing Record now, because I used to record everything, and realised that a lot of what I’d recorded wasn’t very good. That has made me more careful and honed my creative process. I now listen more than I record. It has to be worthwhile and meaningful for me to make recordings. That connects me to the recordings in a personal way, whether it’s the habitat, landscape, animals, people or the processes.

“I’ve got a lot of interesting recordings and I sometimes revisit them, but I’m more charged with the potential for doing stuff in the future and revisiting those sounds with microphones, rather than listening to old recordings.

“But one thing I do like about going back to old recordings is comparing things. So the documentation part of it is really useful, because it allows me to listen back in time to what a place was like. It’s much more interesting than looking at photographs.

“Recently I was listening through recordings that I made not long after we moved to where we are now in Newcastle and our twin boys were born, 25 years ago. I was always recording the garden, because I was interested in the changing seasons, and the sound of the garden has radically changed in 25 years. For example, the place was full of sparrows, and they’ve virtually disappeared, although they are coming back now. It is a lot wilder, more overgrown and is less manicured, so you have to fight your way into it now, which is fine because there’s far more wildlife in there.

“I always take a notebook and keep a diary when I’m recording, but our recall ability is amazingly powerful, particularly for sounds, so I can put a recording on, almost at random, and it instantly takes me back to that place, whether it’s my garden, the Arctic, or the Masai Mara. Like a favourite piece of music, within a few seconds you can remember the first time you heard it, the place where you made those recordings, what it was like and how you felt. So I rely on memory, which is jogged by diaries and notebooks.”

Flying Solo

Chris Watson’s recording work varies from completely solitary to very collaborative, and both extremes have their appeal. “I really enjoy the collaborative part of film‑making, where everything is compromised for the good of the end result. I like the discipline of that. But a lot of my work is solitary and I probably prefer being in control of my own circumstances and events. I learn a lot from film crews and production, but I also like the isolation. Once you put those headphones on, only you can hear the world like that. You disappear into a unique environment.

“I work on film, television and natural history documentaries for all sorts of organisations, but I also get commissioned to make my own work, for which I have a different approach, although the techniques are very similar.

“I like the compositional and production process of making a piece of work which is broadcast to people in its widest sense. Earlier in the year I was making a series of recordings to present at WOMAD, for example. I was in the Scottish Highlands at three in the morning, recording sounds to present to a group of people, so they can hear what I heard on location.”