Is it possible to transfer everything from your existing Windows music computer to a new machine, or should you start afresh?

The time inevitably arrives for each of us when we need to upgrade our music-making PC. As well as figuring out the spec of the new machine, you’ll probably ask yourself whether it’s better to start with a blank page — a new machine, with a clean OS installation, and freshly installed audio software — or to attempt migration of your existing OS, software and hardware to the new machine.

Should I Start From Scratch?

Most retailers advise opting for a completely fresh installation, partly due to the very real obstacles to system migration that existed back in the days of Windows XP (and earlier). With these older operating systems, the transfer from one machine to another of a system drive could be riddled with pitfalls, even for experienced users. As these versions of Windows relied on the registry information being correct during startup, extreme shifts in hardware could even halt the Windows startup process completely — you’d never even reach the desktop!

Thankfully, system-drive migration is now usually a much simpler and safer process for everyone. Windows 7 and onwards are less reliant on the registry information during startup, and can access their large pool of default drivers if an unexpected hardware change is discovered during the boot process. In many instances, if a problem is identified Windows will still load and you can search for a solution. In short, it’s no longer essential that you start from scratch on a new machine.

But there are still strong arguments for a fresh installation. For starters, your new machine will employ different hardware from your old one. There’ll be changes to the BIOS and how the OS needs to operate with it, and any settings and tweaks you or the manufacturer/vendor applied to your previous system might not be appropriate for your new one. Also, your old machine may have older drivers with auto-load services, or self-starting software that’s no longer needed. Any of this could prevent your new system performing to its potential, and by starting anew you avoid these problems entirely.

Of course, there are down sides, too, foremost of which is the time it takes. A new computer might come with the OS pre-installed and it’s easy to move data drives, But installing and configuring the DAW itself, your plug-ins, your hardware drivers, and any other software you require on the machine can be very time-consuming. You can mitigate this to some extent by copying items such as DAW preference files, but if spare time is hard to come by, or your audio projects involve tight deadlines, you might do better attempting a ‘system migration’.

With all this in mind, let’s consider some challenges you might meet when trying to migrate your existing system to a new machine, as well as some strategies for minimising potential problems.

Migration Prep

Acronis True Image is one of a number of tools you can use to clone an existing hard drive.When I use the term ‘migration’, I’m generally thinking of transferring the physical hard drive(s) from one machine to another. Of course, there are also times when you’ll want to move to a new drive at the same time — perhaps, for example, your old system is based around a hard-disk drive (HDD), or perhaps a RAID setup (see 'It's A RAID!' box), and you want your new machine’s OS installed on a faster solid-state drive (SSD). If that’s the case, I’d suggest moving your OS to the new drive on your old machine first, and then migrating that physical drive to the new machine.

Acronis True Image is one of a number of tools you can use to clone an existing hard drive.When I use the term ‘migration’, I’m generally thinking of transferring the physical hard drive(s) from one machine to another. Of course, there are also times when you’ll want to move to a new drive at the same time — perhaps, for example, your old system is based around a hard-disk drive (HDD), or perhaps a RAID setup (see 'It's A RAID!' box), and you want your new machine’s OS installed on a faster solid-state drive (SSD). If that’s the case, I’d suggest moving your OS to the new drive on your old machine first, and then migrating that physical drive to the new machine.

There are commercial disk cloning tools such as Acronis True Image and Paragon Drive Copy, as well as some free options including Clonezilla. Note, however, that a straight cloning of your existing drive is unlikely to go smoothly: although there’d be a bit-for-bit transfer of the actual data to the new drive, a difference in the drive layout may still stop the BOOTMGR (boot manager) from running when you turn the computer back on. I’ll discuss how to troubleshoot this later in the ‘BOOTMGR Is Missing’ section, but it’s worth noting that you can create a rescue boot disk to fix the bootloader outside of Windows. NeoSmart sell a tool to handle this but, as with other third-party options I’ve seen, it's a chargeable rescue disk — however, if you have the Windows installation disk to hand, you can achieve this manually:

1. Boot from the DVD. If prompted, press any key to start the Windows installation process.

2. Choose your language when prompted and click Next.

3. Click Repair Your Computer, and then select the operating system you wish to repair.

4. Select the Command Prompt option and try the following commands (a single command may work, or you might need to use multiple commands, depending on the problem): (a) bootrec /rebuildBCD; (b) bootrec /fixMBR; (c) bootrec /fixBoot

Users of Windows 8 or 10 can also try ‘automatic repair’ from the same DVD installation menu, though while this may solve the issue, I’ve found the command line method more reliable.

Before attending to your drive(s), there’s some other preparatory work you should do. Start by removing any software that’s not relevant to the hardware in the new machine. This helps prevent any software that may no longer be required by the new setup from running at startup, which in turn should help speed up your Windows load time, and keep the OS resource requirements down.

You’ll also need to revoke the licences of any software whose authorisation is tied to your computer hardware, so you can authorise the software on the new system without too much hassle. Notably, such software includes any iLok licences registered to the system using hardware IDs rather than a physical iLok dongle. Moving the drive without first revoking these will probably result in a time-consuming email exchange with the software manufacturer before you can get back up and running. You might also consider transfering hardware-authorised iLok licences to a physical iLok — you can transfer the authorisations from the dongle to your new computer later, if you wish.

The Physical Drive Transfer

With just a couple of connectors and screws to undo and reconnect, physically transferring a hard drive to a new machine is easy.With your licences revoked/transferred, shut the system down, unhook it from the mains and transfer the physical hard drive(s) into the new system — hard drives are normally held in place by four small Phillips-head screws and, once they’re removed and the data and power cables disconnected, the drive should slide out easily. Simply reverse this process to install the drive in the new machine.

With just a couple of connectors and screws to undo and reconnect, physically transferring a hard drive to a new machine is easy.With your licences revoked/transferred, shut the system down, unhook it from the mains and transfer the physical hard drive(s) into the new system — hard drives are normally held in place by four small Phillips-head screws and, once they’re removed and the data and power cables disconnected, the drive should slide out easily. Simply reverse this process to install the drive in the new machine.

Once the drives are connected, you can go into your computer’s BIOS and check that the drive is showing up. This is the ideal time to perform any desirable BIOS tweaks, such as disabling any unused ports and system features you don’t require — this prevents the system detecting and loading drivers on the first boot up. In the BIOS, there’ll be a submenu devoted to the drives and the system boot order. You shouldn’t have to do too much here, but ensure the OS drive is at the top of the boot order list so it’s detected on startup. If it isn’t already first in line, you can manually adjust the order, but a better practice is to ensure it’s at the top by physically attaching the drive to Port 0 (zero) on the motherboard, which can prevent further unexpected issues in the future. The same advice also applies whenever you install a single drive intended to function as your OS drive — check the labelling on the motherboard or consult the manual to establish which port is SATA 0.

Although Windows can be installed on any drive, if it’s connected via an onboard drive controller the computer will write the Master Boot Record (MBR) to the drive plugged into SATA 0, rather than the OS drive. This can present problems post-installation — any complete clones or backups you attempt to create may end up missing this crucial piece of information, and you may be unable to recover your system fully from them. Furthermore, the failure of a drive holding the MBR or the OS data itself will stop the OS from being functional; splitting the OS installation over two drives in this way doubles the risk of failure.

BOOTMGR Is Missing!

But what if this has already happened, and on booting the new machine you’re greeted only by a black screen bearing the dreaded ‘BOOTMGR Is Missing’ message? This denotes a lack of MBR on the current boot drive — the computer can’t find Windows in order to run it. Explaining all the options to explore to resolve this would fill many pages, and there are a multitude of in-depth guides to working around this online. But I’ll cover the basics to point you in the right direction...

If you encounter the dreaded BOOTMGR Is Missing screen, there are ways to tackle this manually, but tools such as Easy BCD can make the process easier.

If you encounter the dreaded BOOTMGR Is Missing screen, there are ways to tackle this manually, but tools such as Easy BCD can make the process easier.

If you’re coming from a system where the MBR is on another drive, the simplest fix is to place the drive back in the old machine, boot to Windows and follow one of Microsoft’s guides to move your MBR to the correct drive. This can involve a bit of Command Line work, but, thankfully, a number of third-party tools can help — for instance, the free (for non-business use) personal edition of BCDEdit, another tool from NeoSmart (https://neosmart.net/EasyBCD), offers a simplified GUI presentation and an extensive set of guides.

If you find yourself in a scenario where you no longer have the old machine, you may find yourself able to build a new MBR from scratch by using the Windows media disk and booting to the Command Prompt to carry out the rebuild. Instructions for this vary slightly from OS to OS, and in-depth guides on the Microsoft support site walk you through the process.

Driver Awareness

When you attempt your first boot back into your Windows desktop, hopefully everything will proceed smoothly — if not, check to see if you need to carry out a few of the extra steps described above. Once you’ve reached the desktop, there will be more system activity on this first boot than normal, as the OS tries to find the appropriate files in its own driver cache, or from the online Windows Update database. Getting it up and running with a basic set of drivers is likely to require minimal effort in most cases, although a ‘rogue’ troublesome driver can sometimes cause the process to halt before you have control of the machine. If that happens, boot Windows in Safe Mode. With Windows 8 and older, pressing F8 just prior to the Windows loading splash screen would take you into a driver- and services-restricted desktop, where you could troubleshoot. With Windows 10 you’ll need to press Shift-F8. You might struggle to do this at the right time, due to Windows 10’s faster boot, in which case Microsoft advise booting from a Windows install disk or a Windows 10 recovery drive (creatable from within any Windows 10 install) — reboot into Safe Mode via the Troubleshooting menu.

Once in Safe Mode, focus on adding the correct drivers for the chipset and graphics card (after removing the old ones), but you can also update any other missing drivers you see in Windows Device Manager. When you’re done, reboot into the standard Windows desktop. This time, as the base hardware is running with correct drivers, the OS should load more smoothly, though you may still need to install other hardware drivers, as some peripherals probably won’t have been detected in Safe Mode. In fact, I suggest more generally trying to ensure all your drivers are up to date at his stage. You may find, for example, that both your old and new motherboards employ the same unified network driver, but while the new one will happily roll along with the older driver, you’ll achieve better performance with a newer one. Get the latest driver from the component manufacturer’s web site wherever possible, as drivers supplied on a CD are likely to be long out of date.

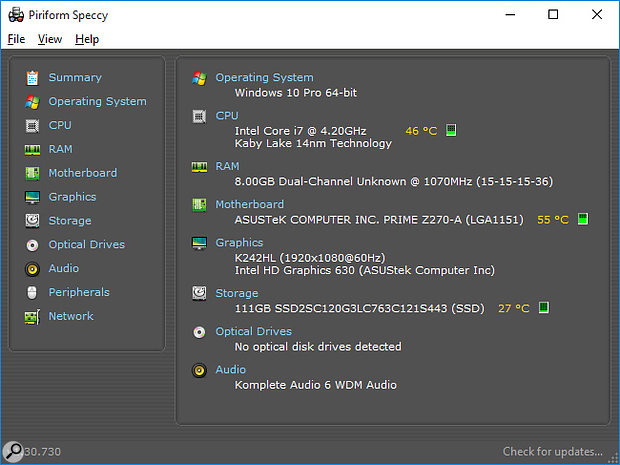

Piriform’s Speccy can help you identify the manufacturer of the various components used on your motherboard — and that can help you find the latest component drivers, which even your motherboard’s web site might not make available.

Piriform’s Speccy can help you identify the manufacturer of the various components used on your motherboard — and that can help you find the latest component drivers, which even your motherboard’s web site might not make available.

Note that motherboards comprise multiple components, and even the drivers on the motherboard web site may not be up to date, so check to see if the component manufacturers offer a newer driver. Whilst it’s fairly simple to ascertain if the chipset is from AMD or Intel, discerning the origin of some of the other devices (such as the wired or wireless networking) can seem less simple. Thankfully, a number of tools can check all the relevant components quickly. My preference is Piriform’s Speccy (www.piriform.com/speccy), whose portable build means it doesn’t need to be installed on the system. Once you’ve run this and have a component list, tracking down the latest drivers should be a breeze.

Some manufacturers claim their software automates the driver-update process for you. These tools have various degrees of effectiveness, but I find they often cause more problems than they solve! A lot of them tend to run in the background, in order to keep you up to date. They interrupt your system with constant checks, which can cause problems for your audio software. For the same reason, note that lots of modern motherboards ship with optional fan- and system-monitoring software — again, these should be avoided, as their constant polling of the system can result in annoying clicks and pops when working with ASIO devices.

Testing The New System: DPC Latency

While you’re updating the drivers, Windows Update should be running in the background to grab the last of any essential system updates. When you’re done, then, it’s time to check that everything’s running as it should. Open a fresh project in your DAW and ensure everything connected to the machine is detected. Perhaps also try loading a few of your DAW’s native synths, to get a feel for how the system is behaving. If the audio is crackling or breaking up, and you’ve checked your interface settings are as they should be, you may have to go back and reinspect the drivers.

To help, you can run a DPC latency check on the system. The DPC figure is a measurement of how long it takes drivers to gain access to and then execute on the CPU. Significant delays can lead to audible corruption when playing back audio. We used to advise using DPC Latency Checker to measure this, but as it has behaved erratically since Windows 8 (the developers are reportedly working to resolve it), I now use Resplendence’s DPC Latency Monitor (www.resplendence.com/latencymon).

Resplendence’s DPC Latency Monitor application is an easy way to test your system’s performance, and to identify any rogue device drivers which might be interfering with your ASIO system.

Resplendence’s DPC Latency Monitor application is an easy way to test your system’s performance, and to identify any rogue device drivers which might be interfering with your ASIO system.

You just click Start, let it run for 5-10 minutes and, once the test is complete, you receive a clear ‘pass’ or ‘fail’, and four meters indicate where problems may potentially arise. A fifth meter (bottom), labeled ‘Pagefault Resolution Time’, can be ignored: it has no real impact on our requirements, and in many cases shows false negatives, due to Windows carrying out work in the background. (The checker ignores this when calculating whether the system passes or fails.)

The main result to consider is the ‘Highest DPC routine execution’. Should the test fail, this ends up red and a suspected culprit driver will be listed, helping you to solve the problem. A common offender is ‘Ndis.sys’, which is a networking issue related to the hardware drivers, antivirus software or, possibly, auto-updating software making callbacks. Graphics drivers also crop up frequently — it’s important to remember always to tick the ‘Clean Install’ box and then select ‘Custom Install’ when installing Graphics drivers, as this allows you to install only the core driver and avoid unwanted extras. Both Nvidia and ATI models, for example, come with utilities that auto-update the driver in the background, which can cause the errors described above. If you run into problems with a current driver, you can try any available beta drivers or an older version, either of which might solve the problem.

Getting Up To Date

A crucial step, when you want to create a high-performing machine, is to get your audio software up to date. With a new install, you should consider ensuring that you’re on the latest build of each of your plug-ins, assuming time permits. Newer plug-in versions may have added features or offer performance gains, and there may also be bug fixes and optimisations for newer hardware configurations. If you haven’t updated since version v1.0 back in 2012, now is a great time to do so.

One issue we already touched on will probably raise its head again too — software licences and copy protection. If you’re using hardware dongles, like a physical iLok or eLicenser, you can continue using them, but for the rest, now is the point at which you must re-authorise any licences you revoked earlier. Despite your earlier efforts, a couple of plug-ins in your collection may still detect a change of system hardware, so do set aside some time to check things, log in to the relevant accounts and re-authorise them.

Conclusions

The migration processes I’ve described above may seem a little daunting, but I’ve been looking at worst-case scenarios at each stage! With a lot of OS moves, especially between hardware from the last three or four generations and when using a single system drive, the process should be fairly uneventful. But being prepared for potential issues and having at least an outline idea of how to tackle them should help you get through it as effortlessly as possible. And with that, I’ll have to leave it to you to decide which approach is best for you!

Your Windows Licence

For each generation of Windows (ie. 7, 8 and 10), there are various ‘editions’. Of most interest to music-makers are the Home and Pro editions, and for each, OEM or Retail licences exist. Functionally, there’s little difference but, crucially, OEM Windows is licensed for use only on the first machine it’s activated on. Retail licences, on the other hand, may be transferred from machine to machine. Suppliers of Windows-based systems are now required to implement Microsoft’s Key management scheme — the Key is ‘injected’ into the motherboard BIOS before being registered with Microsoft, locking the OS to the system hardware for its lifetime. So you’ll need a Retail licence if you wish to migrate the system to a new machine.

If you’re unsure whether you have an OEM or Retail licence, open a command prompt from the Start menu and type “slmgr -dli”. After a few moments, an information panel will appear, displaying the licence type. If yours is an OEM version, you can still migrate your system, but you’ll first need to pay to upgrade to a Retail licence: run the Change Product Key command, found on the System page of Windows’ Control Panel, enter your new Key, restart and it should upgrade it for you. If you go from OEM Home to Retail Pro, you also have the option of doing the Key switch if you boot off the new install media and select Custom Install.

It’s A RAID!

Until recently, a lot of dedicated audio and video computers employed RAID setups (some still do), and if you’re migrating an OS installation from one of these there’s more to consider! If the RAID drives are connected to a PCIe card that manages the array, simply migrating the card as well as the drives should result in a fairly effortless transfer. But if you’re running a native AMD or Intel RAID system, the process is potentially trickier. Migration from one AMD-based machine to another or from one Intel system to another has a reasonable chance of success. Moving from AMD to Intel or vice versa, though, is likely to throw up problems, potentially even leading to loss of data. So this is really something to consider when specifying your new machine.

Given the potential for problems when migrating RAID systems, it’s worth proceeding with caution. To ensure all your data remains intact, you should really clone the RAID onto a single backup drive. Where possible, you should also install the drivers for the new RAID controller before you move the drives — you’re aiming to give the new system everything it needs on its first boot after the changeover. If you created a clone, as discussed above, it’s worth doing a test boot with this prior to making any further physical changes to the RAID setup, in order to be sure that all your data is present and accessible.

Once you’re content that this is the case, the RAID drives can be moved and you can proceed to set them up within the new RAID BIOS, and see if the existing installation works by attempting to boot into Windows. If the data appears to have been lost in the process you can recover it from your backup once the RAID configuration stage is complete. If all this ultimately fails, your only choice may be to resort to a clean install — and having a full clone of your drive to refer too after doing so will ensure that you don’t lose any valuable data in the process.