At the Snapdragon conference, Steinberg demonstrated Cubase running on Windows for Arm, using the native ASIO drivers for a low‑latency electric guitar performance.

At the Snapdragon conference, Steinberg demonstrated Cubase running on Windows for Arm, using the native ASIO drivers for a low‑latency electric guitar performance.

Windows‑based musicians have long been asking for better support at the operating system level — and it seems to be very much on its way, with native low‑latency ASIO drivers and full support for MIDI 2.0. We reached out to Microsoft to find out more.

At the Qualcomm Snapdragon conference in Hawaii in October, Microsoft surprised us all by announcing a new version of Windows for Arm processors with built‑in ASIO drivers for USB 2 audio interfaces. I say surprise, because it marks a big shift from the way Windows has handled audio in the past. The flexibility of Apple’s Core Audio has always been an attractive feature, not least due to its native latency levels, and it’s a feature that lots of Windows‑based musicians have been requesting for many years. At present, this new feature is exclusive to this version of Windows for Arm processors but, importantly, Microsoft say they plan soon to embed USB ASIO support in the more familiar desktop versions of their OS — so it’s potentially very big and promising news for the music‑making community.

The new driver was developed in partnership with Yamaha, the parent company of Steinberg (who developed the ASIO driver protocol) as well as a manufacturer of various USB audio devices and musical instruments, and at the conference Steinberg demonstrated Cubase running on a Snapdragon laptop. They used the native USB ASIO drivers with one of their interfaces to process a live guitar signal with great low‑latency performance. Seeing this sort of performance (it’s on YouTube if you’re interested) on a native hardware driver in a Windows environment was certainly refreshing.

Several notable developments then followed. Shortly after the presentation, a supporting blog post appeared from Microsoft Principal Software Engineer Pete Brown, in which he discussed the announcements and expanded on the new audio developments, which included not only the native ASIO drivers, but also support for MIDI 2.0. Notably, interface manufacturers Focusrite announced their backing for native Arm drivers. Then, a preview build of Cubase for Arm was released a few days after the event, CockOS launched a preview build of Reaper, and Reason announced that a preview of their DAW would be forthcoming.

A number of companies announced that they’d be developing their popular software and hardware audio products for Arm‑based Windows platforms — and more are sure to follow suit.

A number of companies announced that they’d be developing their popular software and hardware audio products for Arm‑based Windows platforms — and more are sure to follow suit.

But what drove this development? Why did Microsoft focus first on Arm processors, and what might it all eventually mean for those using Windows for music and audio? To help me answer such questions, I caught up with Pete Brown, and our interview forms the second half of this article. First, though, I thought it would be helpful to offer some background on the Arm chips supported by this new OS, and to explain why we might be about to see more of them appearing in ‘serious’ music‑making Windows machines.

From Little Acorns...

The Acorn Archimedes: the first widely available commercial computer to feature an ARM processor.Most of us probably know that the M‑series CPUs now used throughout Apple’s product range are based on the chip technology of Arm Holdings PLC, usually known simply as Arm. Apple’s new processors have an enviable reputation for both power and efficiency, but the Arm name (ARM until a 2017 rebranding) and their processors actually go back several decades. The underlying ‘silicon’ concept dates back to the 1960s, but the acronym ARM was first used in 1983 by Acorn Computers, when it stood for Acorn RISC Machine. Conceived to handle simplified code that can be ‘pipelined’ in a relatively efficient manner, RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computer) chips are a competing technology to that used in the Intel and AMD CPUs (known as CISC, or Complex Instruction Set Computer chips) that we’ve become accustomed to using in laptop and desktop computers.

The Acorn Archimedes: the first widely available commercial computer to feature an ARM processor.Most of us probably know that the M‑series CPUs now used throughout Apple’s product range are based on the chip technology of Arm Holdings PLC, usually known simply as Arm. Apple’s new processors have an enviable reputation for both power and efficiency, but the Arm name (ARM until a 2017 rebranding) and their processors actually go back several decades. The underlying ‘silicon’ concept dates back to the 1960s, but the acronym ARM was first used in 1983 by Acorn Computers, when it stood for Acorn RISC Machine. Conceived to handle simplified code that can be ‘pipelined’ in a relatively efficient manner, RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computer) chips are a competing technology to that used in the Intel and AMD CPUs (known as CISC, or Complex Instruction Set Computer chips) that we’ve become accustomed to using in laptop and desktop computers.

Acorn’s first RISC chip appeared in 1987 in their Archimedes desktop computer, which some readers might remember as a more powerful replacement for the BBC Micro in UK schools. But in 1990, Acorn, Apple and VLSI Technology (now NXP Semiconductors) teamed up in a joint venture called Advanced RISC Machines (ARM), which was later listed on the stock exchange and became the Arm we know today. Along with VLSI, Acorn developed the early ARM cores, but it was Apple who first used one of these chips in a general‑market product: their Newton PDA announced in 1992 featured an ARM6 chip. The Newton struggled to establish itself in the face of competition from the Palm Pilot, and its commercial failure led ARM to embrace a different business model: rather than create end‑user products, they’d license their IP to production partners, who would make their own chips based on ARM’s RISC technology.

Apple’s move from Intel to Arm‑based CPUs may seem relatively recent, but along with Acorn they were one of ARM’s founding companies and began selling their first ARM‑powered device, the Newton, way back in 1993.

Apple’s move from Intel to Arm‑based CPUs may seem relatively recent, but along with Acorn they were one of ARM’s founding companies and began selling their first ARM‑powered device, the Newton, way back in 1993.

Starting with the Nokia 6110 GSM phone, which appeared in 1997, their chips found favour in the mobile devices sector, and today they are reportedly found in 99 percent of smartphones. Of course, we’re more interested in their potential for ‘serious’ machines that might be used for music making, so it’s perhaps of greater interest that, in 2012, alongside Windows 8, Microsoft brought out the 32‑bit Windows RT OS for ARM‑based mobile devices. This was used for the Surface tablets and a small number of third‑party devices, all built around Nvidia Tegra 32‑bit ARM processors. Ultimately, the platform’s inability to run popular PC software meant that these devices were largely passed over for more traditional x86‑based laptops.

Then, in 2016, Microsoft launched a 64‑bit ARM version of Windows 10 for Qualcomm’s Snapdragon devices. Hardware shipped over the following years from Microsoft, ASUS and HP, amongst others, but the platform failed to capture users’ attention from the more powerful PC laptops and desktops already on the market and, again, it wasn’t regarded as a commercial success.

Meanwhile, Apple had been successfully using their own custom ARM chips in various devices, including iPads and iPhones, since 2009. But in June 2020 they signalled that they’d be moving from Intel to Arm‑based processors for their more powerful desktop and laptop machines. Their M1 chip first appeared in a product at the end of 2020, and the M‑series chips are now found throughout their product range. Importantly, these Apple chips have enjoyed a good reputation for both power and efficiency, and the products have proved commercially successful.

Right Here, Right Now

This brings us to the present day. As you’ve probably gleaned, in the past it was often software incompatibility that limited the user appeal of older Windows‑based ARM devices. But the emulation layer has matured over the years, and there’s also been a steady increase in PC RISC chip performance. Having the flexibility to run existing applications through the emulation layer should help the platform to expand, and with greater uptake the incentive for developers to compile software specifically for Arm should increase too.

With the barriers to wider adoption falling away, various parties (including silicon behemoths AMD and Nvidia) have announced their entry into the Arm computer market, and new hardware is on the way. Small wonder, then, that Microsoft seem keen not only to support the newest Snapdragon X Elite‑equipped laptop models, but also to deliver the sort of accessible, more streamlined experience that should make the platform attractive for typical computer users.

With ample power and superb battery life, Snapdragon X Elite‑equipped laptops now have the potential to be great portable music‑making machines.

With ample power and superb battery life, Snapdragon X Elite‑equipped laptops now have the potential to be great portable music‑making machines.

Pete Brown & The ASIO Team

That’s not the briefest of technical backgrounds for a music‑focused mag, I know, but I think it’s important context for what follows. Through several roles since joining Microsoft in 2009, Pete Brown has often been a public face for the company, with official titles like Program Manager, Evangelist and Developer Advocate. However, he has always remained first and foremost an engineer, and he spends much more time writing code than any of those official role titles may suggest. When I caught up with Pete, I started by inviting him to explain how he’d been involved in this latest project, as well as in the music/audio side of things more generally.

Pete Brown of Microsoft.“My day‑to‑day [work] at Microsoft,” Pete explained, “involves working with several partner teams like the Audio team, Surface engineering and others, to help make Windows a great place for musicians to be productive and happy. I co‑engineer with different teams on things like the new MIDI stack in Windows, where I wrote the app SDK, tools, loopback and app‑to‑app transports, all of the MIDI 2.0 protocol management and the upcoming Network MIDI 2.0 and Bluetooth MIDI 1.0 transports.

Pete Brown of Microsoft.“My day‑to‑day [work] at Microsoft,” Pete explained, “involves working with several partner teams like the Audio team, Surface engineering and others, to help make Windows a great place for musicians to be productive and happy. I co‑engineer with different teams on things like the new MIDI stack in Windows, where I wrote the app SDK, tools, loopback and app‑to‑app transports, all of the MIDI 2.0 protocol management and the upcoming Network MIDI 2.0 and Bluetooth MIDI 1.0 transports.

“Alongside this, as Chair of the Executive Board of the MIDI Association [the standards body and trade association for MIDI], and as someone participating in the working groups there, I also do my best to help ensure that any new standards will work great on Windows, and that Windows‑based musicians are represented in the discussions.

“In addition, I run the Windows Developer MVP [Most Valued Professional] program, which recognises advocates and leaders in the developer community, and also tend to be heavily involved with our Build developer event, run every Spring.”

One of the more recent ventures keeping Pete’s team busy has been the Windows for Arm project discussed at the top of this article. This included offering support to software developers who are looking to move to the new platform and develop native solutions. I asked Pete to tell us a bit more about the team working alongside him: “The all‑up lead for Arm64 on our team is Marcus Perryman. He deserves a shout‑out for all the great work he’s done to help unblock the vast ecosystem of applications and middleware for Windows on Arm. I also work with Jason Cook here, who does a lot of partner management, specifically on creative apps. I’ve been providing guidance to partners on which compilation targets to use for things like VST plug‑ins, hosts, and also to help unblock them when they run into third‑party components that don’t yet have Arm64 support.

“I’ve also been working closely with Qualcomm and other silicon partners to support creators and specifically musicians on Arm64 PCs. PJ and Rami at Qualcomm have been huge advocates for musicians on the platform, and together we worked to create the musician theme at Snapdragon Summit... complete with musicians performing live on Cubase on Snapdragon PCs, and even a skit in the Jimmy Kimmel show. It’s been fantastic working with them, and especially with PJ, who is a huge fan of this area. I knew I found the right partner there when I saw his EVH guitar hanging on the wall behind him on our first call.”

Why Now? Why Arm?

Next, I wanted to tackle what I consider ‘the big question’. Right since the creation of ASIO, having a low‑latency driver option built into the OS has been a very popular request, and it’s something that could really simplify the setup process for many people recording and processing audio. Just how and why, after all these years, did support for ASIO become a focus for Microsoft?

Pete started by explaining some of the practical difficulties they’ve faced over the years. “Windows is a general‑purpose operating system that has a lot of different types of users. On the PC, you see everything from casual media consumption to high‑FPS gaming, to visual and audio art. Each has different requirements for audio. For example, for media consumption like watching a video, you can have large audio buffers which minimise the number of times rendering and output threads have to wake up to service the buffers, which results in much better battery life. For gaming, FPS is king. Audio is important, but secondary.

“For live music performance, of course, we want audio to be as near‑real‑time as possible, without glitching, with all other concerns being secondary. Add to that that musicians have very different I/O needs, and don’t necessarily want an additional codec or on‑chip processing to, say, compress the audio so it comes out of laptop speakers better. Finally, musicians typically want to lock a sample rate and not have any up/downsampling or bit‑rate translation, whereas normal Windows app expectations are that they supply the data in the format they have, and Windows will resample and mix as necessary to match the hardware.”

He then explained how he and colleagues started to make progress, and why they started with Windows for Arm. “For years, I’ve been working with the audio team, kicking around ideas for how we can make low‑latency audio a reality on Windows, without breaking existing applications, harming battery life or the average user experience, while adding things like device aggregation. Back in 2015, we introduced a low‑latency WASAPI mode, which didn’t require exclusive mode but still allowed lower latencies than the usual approaches. Some applications, like Cakewalk Sonar, tried that out but most didn’t, because the ASIO API was just so much easier for them to work with for pro audio tasks.

“Meanwhile, Arm64 devices ran the risk of receiving limited pro audio support because many hardware companies were not creating Arm64 native ASIO drivers for in‑market products, with even fewer considering creating Arm64 drivers for older devices (which are no longer sold but may still be popular). It’s important to note that while apps can run under emulation, kernel drivers cannot, so they must be developed/recompiled specifically for Arm64.

“So I proposed that we ‘meet them where they are’, and officially adopt ASIO as an interim measure on Windows. The intent is to unblock music creation on Windows on Arm devices for all USB Audio Class 2 devices, whether they are current in‑market [audio] devices or older models that are no longer sold. This means app developers wouldn’t need to adopt a new API, and audio devices will ‘just work’ on Arm64 PCs.” But he also stressed that it isn’t just about low‑latency audio. “Although we often refer to it as ‘the ASIO driver’, the ASIO component is just one piece. The new kernel driver coming out of the project will replace our current in‑box USB Audio Class 2 driver, which has higher latency and doesn’t support the required number of I/O ports. Besides being a great low‑latency driver, the new driver also incorporates best practices for handling power management events without audio glitching, and uses the newer ACX (Audio Class eXtensions).”

Yamaha

I was curious to understand how this all lead to Yamaha’s direct involvement as a partner, helping to implement the native ASIO support. “We’re really excited to have Yamaha as a key part of this project,” Pete enthused. “Yamaha are one of the largest manufacturers of musical instruments and hardware, they also create the audio interfaces for Steinberg and are one of a handful of companies that create their Windows audio drivers in‑house [rather than] purchasing from a third party. This gives us the confidence that they can deliver a top‑quality driver that prioritises musician features and workloads without compromising the consumer experience.

“I’ve worked with Yamaha for years through the MIDI Association and the counterpart in Japan, AMEI, and they were also involved in our MIDI 2.0 project through AMEI. Qualcomm, Microsoft and Yamaha got together and came to a business agreement, which resulted in Yamaha writing the driver and putting all the open‑source‑compatible pieces on a Microsoft GitHub repo, similar to the MIDI 2 driver.

“Yamaha are creating the Arm64 driver and putting it on our repo, using guidance and participation from Microsoft, and Microsoft are then ingesting that into Windows to deliver in‑box for Arm64. We’re adapting this code for Intel/AMD x64, so we can ship in‑box on those architectures.”

Latency & Other Features

SOS readers will probably understand just how demanding of a computer real‑time tracking of a guitar can be while monitoring through virtual amps and effects. When Steinberg used their budget‑friendly Steinberg IXO22 interface to do this at the Snapdragon conference it seemed to work flawlessly, but I wanted a bit more detail about the sort of latency figures we can hope to see when we put the new native driver through its paces. “In a recent YouTube show,” Pete told me, “PJ from Qualcomm mentioned that the setup with the early preview drivers used at Snapdragon Summit was resulting in 4ms round‑trip latency. That was with guitar processing plug‑ins on one PC and synths and orchestral libraries on another. I haven’t measured the driver performance myself yet, but that early result for an inexpensive USB audio device is very promising!”

Historically, routing audio signals from ASIO to non‑ASIO apps, for instance getting a signal from Cubase into OBS for streaming, has been challenging for end users — it often requires third‑party plug‑ins or audio interfaces with digital loopback that can be addressed by the OS and ASIO drivers simultaneously. With native USB ASIO support, I asked, could we expect such routing to become more user‑friendly? “The focus of this first release of the ASIO driver,” Pete responded, “is to unblock Arm64 devices so they afford the same music creation opportunities that x64 users have today. So we’re not adding any big features to ASIO at this point. The good thing is that the driver will follow our best practices, so both ASIO and normal Windows audio can be used at the same time with the same device. That’s something many ASIO drivers do not support today, and which complicates a lot of scenarios.”

I also asked about a popular feature of Apple’s Core Audio: the ability to create aggregate devices, whereby multiple audio interfaces can be made to appear as one larger interface to software running on the OS. Might we expect to see something like this coming natively to Windows? “It’s not something we’ll have support for, at least not in the initial release build. But we know it’s a huge community request, and something I’d personally like to see us do in the future.”

Pete Brown: Although Arm64 devices are the immediate need, we’ll support this in Intel/AMD x64 devices shortly afterwards, helping make the music creation experience truly plug & play across all devices.

Wider Roll‑out

Pete confirmed that “although Arm64 devices are the immediate need, we’ll support this in Intel/AMD x64 devices shortly afterwards, helping make the music creation experience truly plug & play across all devices.” I asked how soon that might be and though he couldn’t be precise, I found his answer encouraging: “Shortly after the USB driver is released on Windows 11 for Arm64,” he reaffirmed, “we intend to release it for Intel/AMD x64 as well. We’ll want to do some additional testing there because there’s a larger backwards compatibility requirement, but it’s certainly something that we are working towards.”

Not all audio devices use USB 2, so I also enquired about whether Microsoft had plans to develop native ASIO driver solutions for other devices. “USB Audio Class 2 devices are the most popular audio interfaces out there today, so of course that’s what we want to unblock first. PCIe and Thunderbolt would also be great to do, but there’s no audio class standard for those — each driver is bespoke so, even on macOS last time I checked, those devices use vendor drivers. I’m an RME PCIe user on my main PC, so I’d love to see a standard there, but that’s a really tall order and a multi‑year cross‑company commitment.”

Neural Processing Units

As on a number of current‑generation laptop chips, the latest Snapdragon processors feature dedicated NPUs (Neural Processing Units), and there are dedicated AI‑ready co‑processors that we can expect to see leveraged for audio processing in the future. Knowing that packages like Algoriddim already use this sort of capability to handle real‑time stem unmixing, I asked if Pete knew of any other software on the horizon that might take advantage of this hardware in an interesting way. “There are,” he replied, “a number of music creation apps that use AI models under the hood for various things. I’ve been working with some of them to help them accelerate their ONNX [Open Neural Network Exchange] models on the NPU (and GPU when an NPU is not available) [but] I have nothing to announce yet...

“Outside of music creation, we announced a number of apps at the Snapdragon Summit and at Microsoft Ignite, including Adobe products, Affinity products, Capcut and others, all of which are using the NPU on Copilot+ PCs to reduce CPU load, improve battery consumption and speed up their workloads. There are many others, especially in the creative space. We’ll see a lot more of this in the future.

“Or perhaps,” Pete clarified, “it would be more correct to say we won’t see a lot more of it — the intent is for this to be transparent to the users of the apps. Instead of screaming “HERE COMES SOME AI!!!” it’s more about making something possible that wasn’t previously possible, or improving something that was not quite as good in the past.”

Major MIDI Refresh?

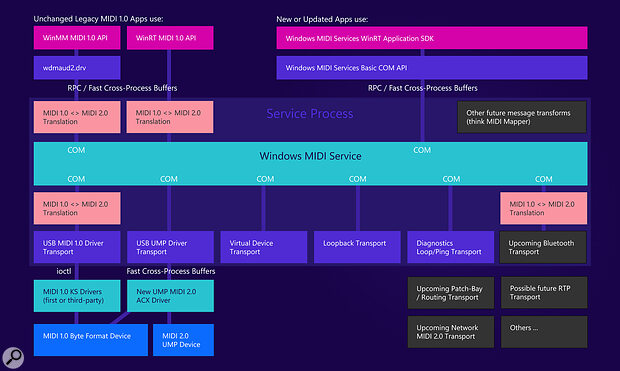

Above, I mentioned Pete’s deep involvement in MIDI 2.0, and in Microsoft’s announcement was the news that MIDI 2.0 support will also be included in Windows for Arm. You can read a bit more about the update to Windows MIDI services on one of his blog posts here: https://devblogs.microsoft.com/windows-music-dev/windows-midi-services-oct-2024-update. To conclude our interview, I invited him to explain more about just what is due to be introduced, and when we can expect to see it. “Our Windows MIDI Services stack delivers for Intel/AMD x64 and Arm64 simultaneously,” he explained. “The ASIO work will deliver first for Arm64 devices to unblock them. Each time we ingest the driver from the repo, we’ll internally recompile it for all supported platforms. Chances are, we’ll deliver for Intel/AMD x64 very close to the time that the Arm64 support is rolled out. It’s really about ensuring we don’t break any current good user experiences, and that performance is what we expect it to be.

Windows MIDI Services architecture diagram.

Windows MIDI Services architecture diagram.

“Windows MIDI Services is our first big update to MIDI in Windows in decades. Not only does it support MIDI 2.0, but it also has a lot of features folks have been asking for for years. It includes built‑in app‑to‑app MIDI and loopback MIDI, increased USB performance, incoming and outgoing timestamps which can be used to schedule messages, full multi‑client support so multiple apps can use the same device, a flexible transport system, which makes it much easier to develop new transports without having to create kernel drivers, a suite of native tools and utilities, and much more.

“Windows MIDI Services is in Windows Insider Canary [preview] builds now, where developers are testing their scenarios and specifically the backwards compatibility with the older WinMM [Windows Multimedia] API. I put a video on YouTube showing how apps which haven’t updated to the new API are able to take advantage of some of the features, including multi‑client support, with no changes at all. It’s not quite ready for non‑developer consumers and musicians just yet, but we are getting very close.

“At this point, we’re really trying to ensure that all those existing apps out there continue to work without changes; this requires a lot of testing as well as development work. New apps using the new SDK will get all the features, including app‑to‑app MIDI, just by using the SDK.

“At the NAMM Show in January [2024], in addition to showing DAWs that are using the new SDK and those that are working with the backwards compatibility support, we had a preview of our Network MIDI 2.0 transport for Windows MIDI Services. The standard was just approved this past November. This transport is a big deal, and will probably end up being more common and more important than even USB today. No USB cable length limitations, plus more than enough bandwidth for multiple MIDI devices.”

If you’re interested, you can learn more about Windows MIDI Services at https://aka.ms/midi.

Emulation & Compiling Applications Under Arm64EC

Pete offered me a lot more detail on how Windows for Arm would handle emulation for software compatibility. An emulation layer effectively translates code developed for one architecture so that it can be run on another (for example, Rosetta made it possible to run Intel Mac apps on the M‑series Macs). Below, I’ve summarised — mostly in Pete’s own words but with some paraphrasing and clarification for those less familiar with the subject — what Pete shared with me below.

The ‘EC’ in Arm64EC stands for Emulation Compatible, and while it’s native Arm64 code the stack layout is also compatible with Intel/AMD x64, so at a function level you can easily go from Arm64 to x64 and back to Arm64 again, seamlessly. To support this, there are four options developers can choose from when developing with Windows on Arm in mind:

1) Stay as Intel/AMD x64: The application will run under Prism emulation and this now supports emulating vector instructions. These are the extended instruction sets found in chips, the most well‑known example being the AVX family which can speed up certain tasks within the CPU, and are native to CISC chips. Emulating this functionality improves the handling of software that requires AVX support to run normally.

2) Hybrid x64 and Arm64: This requires Arm64EC. The scenario here is partial migration of an app. That could be either an app with dependencies that aren’t currently compiled to Arm64, or an Arm64 app which loads your existing library of Intel/AMD x64 plug‑ins. The Arm64 code runs natively, while the x64 code runs under emulation in the same process.

3) Pure Arm64: This offers no compatibility with Intel/AMD x64 code (or Arm64EC code), but it offers all the Arm64 registers, so may have slightly better performance for some specific workloads.

4) Arm64X: Arm64X combines Arm64 and Arm64EC in the same binary. Pure Arm64 processes load just the Arm64 code, while x64 and Arm64EC code loads the EC code. The key advantage is that a single binary (a DLL, for example) contains both in a space‑saving format, and that’s important for things like ASIO drivers and VSTs, which apps need to load without having to worry about their architecture. This is how Microsoft ship most in‑process code on Arm64, including the Windows MIDI Services SDK, and is how Pete recommends VST and ASIO driver developers ship their code.

MSBuild tools are designed to make the process of compiling for these different targets quite easy, though some developers will need to modify their build process to more easily support them, especially Arm64X, which has a novel approach to how it builds. That’s something Pete and his team have been helping to advise on. Some programming tools today, like Delphi, do not support creating Arm64 binaries for Windows on Arm at all, so apps built using those tools will run under emulation. Pete tells me that when they run across instances like this, they reach out to the company to help them prioritise Windows on Arm in their future plans.

Recompiling code for Arm64 or Arm64EC is usually quite easy, and any complexity developers run into usually relates to special vector instruction libraries, which are different for Arm64 and Intel/AMD x64. For some developers, there’s no hurdle and they can port very quickly. Others might need to fine‑tune and tweak things to maximise performance. But there are DAWs written using very low‑level coding, like Reaper, that have quickly spun up Windows on Arm versions, so it’s really going to depend on the team’s experience, what library and other dependencies they have, and the structure of their code.

Although Windows has had Arm support for quite some time, the first real performance Windows on Arm PCs have shown up only this year. As a result, the first experience many developers in this industry have had porting to Arm64 was with macOS. Pete says the ones he’s worked with have been able to leverage the things they’ve already learnt doing that port, to make their port to Windows on Arm a much easier process.