Recording an acoustic guitar duo in two separate rooms means great separation, but a lot of work to make the different spaces sound alike!

Back in SOS January 2016, I wrote about helping guitarists Christian Bolz (www.christianbolz.de) and Tobias Knecht (www.tobiasknecht.de) record high‑quality demos for themselves in their basement rehearsal room. On the face of it, helping musicians create their own recordings might appear like career suicide for a jobbing audio engineer such as myself, but most musicians I know hate techy chores, so even if they can record themselves, they’re usually thrilled to delegate at the first available opportunity! And in that event, of course, their second question after “How much can we afford?” is almost invariably “Who do we know?”, so if you’ve already planted in their minds that you’re (a) fairly competent and (b) not trying to rip them off, then you may suddenly find yourself top of their shortlist.

Fortunately for me, that’s exactly what happened in this case, because they subsequently asked me to record their full‑length debut album. However, for that record they wanted to aim for a more modern and ‘produced’ sound, in recognition of their move into increasingly complex and percussive fingerstyle arrangements, so we had to change our tactics substantially. In the first instance, it was quickly agreed that we should acoustically isolate the two players to make best use of session time (we only had a couple of days to record 26 bits of music!), so we could comp freely between takes during editing, and independently process each instrument at mixdown. With this in mind, I suggested that we use the nearby Mastermix Studios, because its glazed isolation booth would maintain a sightline between the players, and we’d be able to take advantage of its great collection of mics and preamps into the bargain.

When In Doubt, Cheat!

During our pre‑session discussions, the guys played me some commercial records that had inspired their new direction, and in particular a track called ‘Boogie Shred’ by renowned virtuoso Mike Dawes. I’d previously mixed a record for another fingerstyle wizard called David Youngs (http://davidyoungs.net), so I already had plenty of ideas about how to approach the project from that angle. To be frank, though, I was far less confident about how best to record the instruments in the first place to facilitate that kind of end result. So I cheated!

What I mean by that is that I checked the credits on ‘Boogie Shred’ and Googled the engineer responsible, who turned out to be the wonderful Josh Clark of Get Real Audio (www.getrealaudio.com). I find that studio folk are, on the whole, happy to respond to polite technical inquiries, but Josh was uncommonly gracious, providing masses of detail about his recording and mixing tactics — what a gent! Now, it’s worth clarifying that I didn’t plan simply to copy his setup; there would be little point in that, given that I was recording different music, different players, and different instruments in a different room! Nevertheless, there were plenty of ways Josh influenced my plans.

For a start, the presence of an omni Oktava MK012 within Josh’s close‑mic line‑up reassured me that I probably wouldn’t go far wrong by adopting an ‘if it ain’t broke’ policy and recording the guitars with the same pair of omni Oktava MK012s that had sounded so appealing for demo purposes. The band and I had both independently bought MK012s following that session, so we could give each instrument its own pair. Whereas I’d instinctively have started out with these close mics a foot or more from the instruments, Josh advised me to bring them within eight inches and then add separate ambience mics, thereby giving more control over both the degree of detail and the depth perspective. In such close proximity to the instrument, I also decided to space the mics less widely than I had in the home studio (about 10 inches apart), to avoid a ridiculously stretched stereo image.

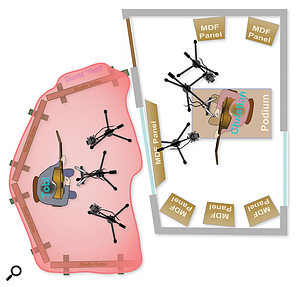

Mike’s setup for recording this fingerstyle acoustic guitar duo: the players are acoustically isolated from each other, while visual contact between them is maintained.Josh’s top tip for the more distant mics were AKG C414 B ULS condensers set up in a Blumlein configuration (ie. figure‑of‑eight polar patterns crossed at 90 degrees). We didn’t have these exact mics available in our case, but we did have access to a pair of C414 B XLSs and a pair of C414 EBs, which seemed like no‑brainer first selections nevertheless. I deviated from Josh’s Blumlein setup, though, for a variety of reasons. Partly it was that I prefer the sound of omnis in general, and partly because I wanted to go for a more spacious and decorrelated spaced‑pair ambient character. However, I also felt that wide‑spaced ambient mics would pick up two different perspectives on the guitar tone, giving a more holistic capture, whereas any coincident pair would only sample one perspective, and might also sound more similar to the tone of the close mics if centrally placed.

Mike’s setup for recording this fingerstyle acoustic guitar duo: the players are acoustically isolated from each other, while visual contact between them is maintained.Josh’s top tip for the more distant mics were AKG C414 B ULS condensers set up in a Blumlein configuration (ie. figure‑of‑eight polar patterns crossed at 90 degrees). We didn’t have these exact mics available in our case, but we did have access to a pair of C414 B XLSs and a pair of C414 EBs, which seemed like no‑brainer first selections nevertheless. I deviated from Josh’s Blumlein setup, though, for a variety of reasons. Partly it was that I prefer the sound of omnis in general, and partly because I wanted to go for a more spacious and decorrelated spaced‑pair ambient character. However, I also felt that wide‑spaced ambient mics would pick up two different perspectives on the guitar tone, giving a more holistic capture, whereas any coincident pair would only sample one perspective, and might also sound more similar to the tone of the close mics if centrally placed.

Another important aspect of the Mike Dawes setup was the use of three different DI signals, so even though the instruments we were using had only one DI output option, I allocated each of the players a Radial StageBug SB4 (specifically designed for piezo pickups). Finally, I planned some spare recording channels in case, like Josh, I discovered that additional close mics were required to capture certain aspects of the performance — particularly the percussion, which involved tapping a variety of different points on the instrument.

Duvets & MDF To The Rescue!

Although I knew placing Christian in Mastermix’s booth and Tobi in the main live room would provide great isolation between the instruments, it did present something of an acoustics problem: the booth was much deader‑sounding, so I was concerned that this would make the two instruments sound obviously incongruous in the mix, despite their similar miking. As far as reverberation was concerned, there was no way to significantly alter the nature of the booth sound, so I resolved instead to block the live‑room reverb from reaching Tobi’s mics by surrounding him with a ‘tent’ constructed out of the studio’s four tall gobos and my trusty collection of duvets, carabiners and bungee cords.

Because the studio’s isolation booth added almost no reverb tail at all to Christian’s guitar sound, a ‘tent’ was built around Tobi to eliminate the live room’s natural ambience from his sound too, thereby matching the acoustics of the two spaces more closely.

Because the studio’s isolation booth added almost no reverb tail at all to Christian’s guitar sound, a ‘tent’ was built around Tobi to eliminate the live room’s natural ambience from his sound too, thereby matching the acoustics of the two spaces more closely.

A difficulty with recording acoustic guitar, though, is that it tends to sound best when the mics pick up plenty of early reflections. You see, the instrument’s resonating wooden body has tremendously complex and variable frequency dispersion characteristics, and this means it sounds very different from different angles. Without any early reflections from the environment, each mic picks up only one of these angles, and the recorded sound can therefore lack upper‑spectrum harmonic richness and complexity. So while I was keen to avoid any reverb tail on the guitars, I nonetheless wanted to encourage early reflections.

The booth was very dead‑sounding, so Mike propped up some MDF off‑cuts to reintroduce some natural early reflections and enhance the upper‑spectrum tone of Christian’s guitar.In Tobi’s case, I knew the live room’s hardwood flooring would already work in our favour, but I also decided to arrange the gobos in my ‘tent’ so that their reflective sides faced inwards. The booth, though, had no reflective surfaces other than the window, so I decided to bring a stack of MDF off‑cuts with me to reintroduce some reflections that way. These I leaned against the walls at various points, angled towards the playing position.

The booth was very dead‑sounding, so Mike propped up some MDF off‑cuts to reintroduce some natural early reflections and enhance the upper‑spectrum tone of Christian’s guitar.In Tobi’s case, I knew the live room’s hardwood flooring would already work in our favour, but I also decided to arrange the gobos in my ‘tent’ so that their reflective sides faced inwards. The booth, though, had no reflective surfaces other than the window, so I decided to bring a stack of MDF off‑cuts with me to reintroduce some reflections that way. These I leaned against the walls at various points, angled towards the playing position.

One further setup problem needed addressing: the booth window was a little high in the wall, so Christian and Tobi (who both performed seated) would only really be able to see the tops of each other’s heads. Some pre‑session DIY paid dividends: I bought a thick slab of MDF and some robust L‑shaped aluminium profiling, and used these to build a simple platform that would fit neatly over four of the heavy‑duty plastic crates I use for transporting my recording gear.

Mike put together a DIY podium in the booth to raise Christian’s seated position and improve the sightline between the two guitarists.The resulting podium felt reassuringly solid, had comfortably enough space for Christian’s chair on top, and added another source of early reflections beneath his guitar. Furthermore, because the storage boxes are stackable, I knew I could raise the platform further if the 25cm height of a single layer of boxes proved insufficient. (Few engineers ever really grow out of their Lego phase!)

Mike put together a DIY podium in the booth to raise Christian’s seated position and improve the sightline between the two guitarists.The resulting podium felt reassuringly solid, had comfortably enough space for Christian’s chair on top, and added another source of early reflections beneath his guitar. Furthermore, because the storage boxes are stackable, I knew I could raise the platform further if the 25cm height of a single layer of boxes proved insufficient. (Few engineers ever really grow out of their Lego phase!)

Refining Mic Choice & Positioning

Having developed a clear strategy for the session, implementing it on the day turned out to be relatively straightforward, not least because fellow engineer Simon‑Claudius Wystrach (www.simonclaudius.com) was there to help with building Tobi’s ‘tent’, outfitting Christian’s booth, and line‑testing the mics/headphones while I used some commercial reference mixes to acclimatise my ears to the studio’s control‑room monitors. Following the musicians’ arrival, we all worked together to fine‑tune my initial close‑mic positions in search of the most appealing sound, doing test recordings as we went for discussion purposes.

Whatever anyone tells you, this process inevitably involves a lot of trial and error, but you can use a few principles to steer things. For example, the instrument’s soundhole can be an important factor, because the more on‑axis your mics are to it, the more low‑end ‘woof’ you’ll get courtesy of the instrument’s primary air‑cavity resonance. That’s why I chose to pull my close mics upwards, so that they fired at the instrument from diagonally above. Proximity‑effect bass boost can also be a low‑end issue with directional mics, but the omnis we were using are by nature immune to that.

The other crucial consideration is mechanical noises such as picking transients and fret squeaks, although there’s a limit to how much you can curtail those when miking so close, no matter what you try. I did splay the close mics a little, though, rather than having them in parallel, because even omni mics are somewhat directional at high frequencies, and I wanted to avoid directing their brighter on‑axis sound directly at the picking location. This had a side‑effect of subtly widening the high‑frequency stereo image, but I wasn’t averse to that!

As a rule, it’s easier to get a natural sound with mics that are further away, so it was no surprise that the C414s were fairly straightforward to position once the close mics had been locked down. Although we all referred to these as ‘ambient mics’ during the session, they were actually only a couple of feet away, so they were hardly swimming in reverb. They did, however, provide some useful additional tonal components and plenty of early reflections, and helped to bring the close‑miked sound to life when mixed in at a moderately low level. In common with any multi‑mic rig, I made sure to check for the most pleasant‑sounding polarity relationship between the mics, but otherwise made a point of avoiding EQ during the tracking process — I usually do this, as it forces me to put in sufficient work with my mic positioning!

When Tobi switched from steel‑strung to nylon‑strung guitar, the main close microphones didn’t deliver a suitable sound, so in the first instance Simon‑Claudius tried finding a more appropriate tone by moving the mics while Mike listened in the control room and advised over talkback.

When Tobi switched from steel‑strung to nylon‑strung guitar, the main close microphones didn’t deliver a suitable sound, so in the first instance Simon‑Claudius tried finding a more appropriate tone by moving the mics while Mike listened in the control room and advised over talkback.

The mic setup wasn’t exactly ‘set and forget’, though, if only because the mic signals (and sometimes the DIs too) benefited from rebalancing to adapt their combined sound to each new arrangement. Some tunes were more percussive than others, for instance, and the two instruments frequently swapped lead and accompaniment roles. I also had to contend with each player switching between steel‑strung and nylon‑strung guitars on some of the numbers. Luckily, Christian’s nylon‑string happened to sound pretty good without our changing any mics, but Tobi’s sounded rather dull and congested through his steel‑string rig. Having tried getting Simon to just move the Oktavas while I listened in the control room, even their best‑sounding position wasn’t really cutting the mustard for me, so I decided to swap them out for something brighter.

I’d been struck by the crisp tone of the studio’s vintage Neumann SM69 stereo mic when recording the Don Camillo Choir on a previous session (SOS April 2017: http://sosm.ag/session‑notes‑0417), so went for that over the other stereo pairs we had available (Neumann U87s and KM84s, and Superlux R102 ribbons). I still wanted to maintain a reasonable stereo spread for the close‑mic image, which meant switching the SM69’s capsules to a directional polar pattern, given their coincident configuration. By choosing cardioid, I incurred only a moderate degree of proximity effect, while splaying the capsules to a mutual angle of around 120 degrees slightly centre‑recessed the balance to avoid spotlighting the parts of the instrument closest to the mic. Immediately, the SM69 gave an airier sound, and we soon found a suitable spot for it by ear.

During The Takes

Once the performers had decided on their playing positions, Simon‑Claudius gaffered their chairs and footrests in place to minimise further movements. This meant that Mike wasn’t then chasing a moving target when adjusting mic positions, and it also helped keep the recorded timbre more consistent between takes.When you’re working with very close microphone positions, small movements of the instrument can make big differences to the sound, so Simon and I took a variety of precautions to maximise sonic consistency between takes. The first might seem almost ridiculously obvious: I just made a point of talking to the players about it and asked them to actively decide on their preferred performing position at the outset. Honestly, you wouldn’t believe how often I’ve seen an instrumentalist perform one way while you’re moving mics around, and then suddenly rotate 30 degrees on their chair or lean six inches backward when the red light goes on! Once they’d each committed to their playing posture, Simon whipped out some gaffer tape and fixed their chairs and footrests to the floor to help avoid those positions drifting over time.

Once the performers had decided on their playing positions, Simon‑Claudius gaffered their chairs and footrests in place to minimise further movements. This meant that Mike wasn’t then chasing a moving target when adjusting mic positions, and it also helped keep the recorded timbre more consistent between takes.When you’re working with very close microphone positions, small movements of the instrument can make big differences to the sound, so Simon and I took a variety of precautions to maximise sonic consistency between takes. The first might seem almost ridiculously obvious: I just made a point of talking to the players about it and asked them to actively decide on their preferred performing position at the outset. Honestly, you wouldn’t believe how often I’ve seen an instrumentalist perform one way while you’re moving mics around, and then suddenly rotate 30 degrees on their chair or lean six inches backward when the red light goes on! Once they’d each committed to their playing posture, Simon whipped out some gaffer tape and fixed their chairs and footrests to the floor to help avoid those positions drifting over time.

Another close‑miking problem was that the sound we liked involved positioning the mics above the horizontal plane of the strings, where it was quite close to the players’ heads; breathing noises sometimes became distractingly audible, to the extent that we had to retake on a number of occasions. This was particularly challenging in Tobi’s case, because his guitar was a more live‑oriented model that wasn’t designed to be very loud acoustically, so even clothing rustle became a concern at times, especially during long‑held melody notes and final‑chord fade‑outs, where most performers find it unnatural to remain completely still. Thankfully, Simon kept a careful ear out for these kinds of unwanted sounds during the recording, as well as handling the transport controls and taking documentation, which freed me up to concentrate on a variety of other ‘big picture’ tasks.

Constantly re‑evaluating the balances of your mics in the control room is a great way to confirm whether the miking choices are truly up to scratch.Chief amongst these was continually reworking the control‑room balance. Yes, the bottom line while tracking is the quality of the signals you’re recording, but I think the ‘rough’ mix is a lot more important to the success of a session than many project‑studio engineers give it credit for. For one thing, constantly tinkering with the balance forces you to question how your mic signals are working together, and challenges you to develop a solid vision for the sonics. How do you think the record should sound? And if it doesn’t sound like that, why not? It’s only by playing with my fader levels that I feel I can say with any confidence that I’m capturing what I need for the final mixdown. Or, to put it another way, it’s often the process of struggling unsuccessfully to get a satisfying control‑room balance that alerts me that some mic or other still needs attention in the live room.

Constantly re‑evaluating the balances of your mics in the control room is a great way to confirm whether the miking choices are truly up to scratch.Chief amongst these was continually reworking the control‑room balance. Yes, the bottom line while tracking is the quality of the signals you’re recording, but I think the ‘rough’ mix is a lot more important to the success of a session than many project‑studio engineers give it credit for. For one thing, constantly tinkering with the balance forces you to question how your mic signals are working together, and challenges you to develop a solid vision for the sonics. How do you think the record should sound? And if it doesn’t sound like that, why not? It’s only by playing with my fader levels that I feel I can say with any confidence that I’m capturing what I need for the final mixdown. Or, to put it another way, it’s often the process of struggling unsuccessfully to get a satisfying control‑room balance that alerts me that some mic or other still needs attention in the live room.

A decent tracking mix can also work wonders in terms of gaining the musicians’ trust, especially when you’re working with artists for the first time. Not only does it reassure them that you know roughly what you’re doing, but it also gives them confidence that the hard work they’re doing in the live room will actually translate into the mixed sound they’re looking for. The more you can relieve the psychological pressure on a performer, the greater the likelihood that they’ll deliver wonderful takes. I’m not saying you need to get carried away with heaps of fancy mix processing, but you should at least try to make sure the balance makes musical sense. Personally, I like to ride the faders during playback so that the balance responds to moment‑by‑moment arrangement changes, and on this session I also added a touch of reverb in the control room, because our recording technique had left the guitars drier than we’d want them on the final record.

Being able to wander around the control room during takes also offered some advantages. Even purpose‑designed commercial control rooms don’t maintain a perfectly consistent sound throughout, so I find I get a fuller idea of what the recordings truly sound like if I ‘average the room’, in other words compare my impressions from different listening positions. Furthermore, this walkabout also warns me if there are areas in the room where the sound is horrid, which means I can gently direct the musicians away from those (perhaps by stacking some spare gear there!) and towards more euphonic regions.

Mixing

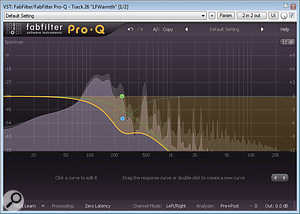

In the end, the hard work we’d done during tracking really paid off, because I was able to get through the mixes at a rate of around three per day. Although Josh had warned me to take special care with the phase relationships between the mic signals, in the event neither guitar sound benefited appreciably from in‑depth phase tweaking, and only the DI signals seemed to combine more solidly with the mics when delayed a few dozen samples. The band’s choice of reference tracks indicated that they wanted a larger‑than‑life ‘smile curve’ mix tonality, which was easily arrived at by boosting the spectral extremes with EQ, but I also gently squeezed the dynamic range of the 1‑5 kHz region to help it maintain its place in the balance, using a multiband compressor at a 1.5:1 ratio with fast time constants. A further stage of fast low‑ratio full‑band compression enhanced the sustain and low‑level detail a touch.

Each mix involved some careful work to balance the mechanical noises and percussive elements with the pitched guitar timbre. A touch of transient reduction and a super‑fast de‑esser smoothed the edges of the picking transients, for instance, while a fast limiter contained the level peaks of the more exuberant percussion elements. At the low end, there were a number of occasions where the thud of the guitarist’s hand on the instrument body (simulating a kick drum) felt as if it was overpowering the instrument’s lower‑string bass notes. To reduce this disparity, I set up a low‑pass‑filtered and heavily compressed parallel channel, fed from both guitars, to bolster all the sustained low‑frequency components. This altered the overall mix tone, of course, but it was easy to compensate by reining in my previous bass EQ boosts.

Each mix involved some careful work to balance the mechanical noises and percussive elements with the pitched guitar timbre. A touch of transient reduction and a super‑fast de‑esser smoothed the edges of the picking transients, for instance, while a fast limiter contained the level peaks of the more exuberant percussion elements. At the low end, there were a number of occasions where the thud of the guitarist’s hand on the instrument body (simulating a kick drum) felt as if it was overpowering the instrument’s lower‑string bass notes. To reduce this disparity, I set up a low‑pass‑filtered and heavily compressed parallel channel, fed from both guitars, to bolster all the sustained low‑frequency components. This altered the overall mix tone, of course, but it was easy to compensate by reining in my previous bass EQ boosts.

In order to improve the balance between low‑frequency percussive elements and the sustained fundamentals of bass notes at mixdown, Mike blended in a low‑pass‑filtered and heavily compressed parallel channel.The thorniest technical issue (as usual when close‑miking acoustic guitars) was fret squeaks, which had been exacerbated by the brightened overall mix tonality. I’ve tried a bunch of different plug‑in remedies for these, but I always end up coming back to the same thing: a simple automated low‑pass filter, which you set to close down abruptly to around 1kHz just for the duration of each fret squeak. Although you might think this would sound rather clunky and obvious, it can work amazingly well — somehow our ears seem to have trouble following such brief changes in tone. Moreover, on any ensemble project, even if the low‑pass filter’s action is a little audible, the artifacts are usually masked by other instruments. On occasion, there’s a bit of an art in setting exactly when and how far to close the filter, and you’ll normally get the most natural results if you don’t try to remove the fret squeak completely — it’s better just to concentrate on smoothing it into an appropriate balance relative to the rest of the performance.

In order to improve the balance between low‑frequency percussive elements and the sustained fundamentals of bass notes at mixdown, Mike blended in a low‑pass‑filtered and heavily compressed parallel channel.The thorniest technical issue (as usual when close‑miking acoustic guitars) was fret squeaks, which had been exacerbated by the brightened overall mix tonality. I’ve tried a bunch of different plug‑in remedies for these, but I always end up coming back to the same thing: a simple automated low‑pass filter, which you set to close down abruptly to around 1kHz just for the duration of each fret squeak. Although you might think this would sound rather clunky and obvious, it can work amazingly well — somehow our ears seem to have trouble following such brief changes in tone. Moreover, on any ensemble project, even if the low‑pass filter’s action is a little audible, the artifacts are usually masked by other instruments. On occasion, there’s a bit of an art in setting exactly when and how far to close the filter, and you’ll normally get the most natural results if you don’t try to remove the fret squeak completely — it’s better just to concentrate on smoothing it into an appropriate balance relative to the rest of the performance.

Here are the two reverbs Mike ended up using at mixdown: a short‑decay chamber patch to provide a sense of space and ‘glue’, and a longer, pre‑delayed plate treatment for subtle extra sustain.For reverb, I applied a combination of two different Lexicon PCM Native Reverb plug‑ins to both instruments. A Medium Chamber patch was the louder of the two in the mix, and was designed to restore the sense of communal space and blend that was missing on the RAW recordings. However, I deliberately shortened this patch’s reverb tail and reduced its bass reverb‑time multiplier, because otherwise it felt too rich and seemed to draw too much attention to itself within the mix. For sustain, I turned to a large plate patch with lots of pre‑delay and high‑frequency EQ cuts, and de‑essed it so that mechanical noises wouldn’t cause distracting high‑end ‘ricochets’.

Here are the two reverbs Mike ended up using at mixdown: a short‑decay chamber patch to provide a sense of space and ‘glue’, and a longer, pre‑delayed plate treatment for subtle extra sustain.For reverb, I applied a combination of two different Lexicon PCM Native Reverb plug‑ins to both instruments. A Medium Chamber patch was the louder of the two in the mix, and was designed to restore the sense of communal space and blend that was missing on the RAW recordings. However, I deliberately shortened this patch’s reverb tail and reduced its bass reverb‑time multiplier, because otherwise it felt too rich and seemed to draw too much attention to itself within the mix. For sustain, I turned to a large plate patch with lots of pre‑delay and high‑frequency EQ cuts, and de‑essed it so that mechanical noises wouldn’t cause distracting high‑end ‘ricochets’.

These reverbs were then combined with all the other channels through a master‑bus chain containing a slow‑acting 2:1 compression setting from Cytomic’s The Glue plug‑in and a 200Hz dynamic EQ cut, the latter another golden hint from Josh Clark — it’s surprising how effectively it eases low mid‑range congestion, and how hard you can make it work before it starts sounding strained.

Guitar Hero

If you take nothing else away from this month’s article, remember that everyone in this industry, at one time or another, needs to seek advice from other engineers to improve their craft. So don’t be afraid to ask peers and mentors for the benefit of their specialist experience and, by the same token, consider it your duty to share your own knowledge with others in turn.