Are buzzes, hums and hisses ruining your guitar recordings? Here’s how to keep the noise to a minimum.

For as long as we’ve had electric guitars, guitarists have had to grapple with unwanted noise making its way into the guitar sound. When playing electric guitar in live performance, hum, buzz, fizz and hiss are certainly not ideal, but you may still feel that a little of it is acceptable. But recorded performances will be heard over and over again, so such noises are likely to be much more irritating. This article takes you through the main causes of electric guitar noise, offers some solutions, and should also help you make the best of things and manage expectations in those situations where at least a little noise is inevitable.

Guitar MOT

A cheap multimeter allows you to check that there’s a zero‑resistance path between the guitar’s hardware and its output jack.Lots of clever plug‑ins attempt to address noise after the fact, but they can’t take care of everything and the more you ask them to do, the greater the side‑effects. In short, the best results always come from eliminating or minimising annoying noises before you record. There are several potential issues that can cause and exacerbate noise problems, and some are more obvious than others, but the best place to start is probably the guitar itself.

A cheap multimeter allows you to check that there’s a zero‑resistance path between the guitar’s hardware and its output jack.Lots of clever plug‑ins attempt to address noise after the fact, but they can’t take care of everything and the more you ask them to do, the greater the side‑effects. In short, the best results always come from eliminating or minimising annoying noises before you record. There are several potential issues that can cause and exacerbate noise problems, and some are more obvious than others, but the best place to start is probably the guitar itself.

The first thing to check is that there’s a zero‑resistance path between the guitar’s hardware and its output jack. To check this, use a multimeter set to Ohms, plug in your regular guitar cable and measure the resistance between the strings and the barrel of the jack plug at the amp end of your lead. The meter should read very close to 0Ω. By the way, checking in this way rules out problems with the guitar lead, which is helpful — if there’s a problem, change the lead; if it goes away there’s your issue, if it doesn’t, the problem is with the guitar...

Usually, the guitar’s bridge is grounded, and this means that the strings are also grounded. Grounding is normally handled by a length of wire inside the guitar that, in the case of a Strat‑type guitar, links the vibrato spring claw to the ground wiring on the control panel. The backs of the pots are common termination points for ground wires, as there’s plenty of area for soldering and most wiring regimes will ground these parts, either using wires or via a metal‑foil lining to the pick guard, through which all the controls are fitted.

Even slight corrosion on the guitar’s jack could be the culprit — a quick squirt of Deoxit should address the problem.A less immediately obvious potential cause of poor grounding is something I experienced when playing a guitar with ‘noiseless’ pickups (stacked humbuckers that are designed to sound like single coils) at a noisier than usual live venue that had lighting dimmers. As you may know, these produce radio‑frequency emissions for which the pickups in your guitar act as antennae. My guitar wiring was all good, the noiseless pickups were Fender stacked humbuckers, and I had a really good guitar cable but I was still picking up a huge amount of interference. My amp was properly grounded too, so where was all that buzz coming from? The culprit turned out to be a slight layer of corrosion on the grounding prong of the guitar’s output jack. This added resistance to the ground path, which can be identified as outlined above. A quick clean and a spray of Deoxit D5 soon had me sorted.

Even slight corrosion on the guitar’s jack could be the culprit — a quick squirt of Deoxit should address the problem.A less immediately obvious potential cause of poor grounding is something I experienced when playing a guitar with ‘noiseless’ pickups (stacked humbuckers that are designed to sound like single coils) at a noisier than usual live venue that had lighting dimmers. As you may know, these produce radio‑frequency emissions for which the pickups in your guitar act as antennae. My guitar wiring was all good, the noiseless pickups were Fender stacked humbuckers, and I had a really good guitar cable but I was still picking up a huge amount of interference. My amp was properly grounded too, so where was all that buzz coming from? The culprit turned out to be a slight layer of corrosion on the grounding prong of the guitar’s output jack. This added resistance to the ground path, which can be identified as outlined above. A quick clean and a spray of Deoxit D5 soon had me sorted.

To get the best from noiseless pickups, it’s also a good idea to screen the control cavity of the guitar using either conductive paint or self‑adhesive copper strip, all of which should be interconnected and linked to the guitar ground.

There are now some very good ‘noiseless’ pickups designed to look and sound like single‑coil types.Another option is to fit active pickups. These tend to have a lower impedance, which makes them less susceptible to induced electromagnetic interference, and their active circuitry matches the pickups to your amp or audio interface. However, many players are wary of them, partly because they need power (typically from either a 9V battery or a USB chargeable lithium battery), and partly because they may not sound the same as the passive pickups to which they’re accustomed. Also, it’s often necessary to partly disassemble the guitar to change the battery if the pickups are a retrofit. So there are pros and cons, but they can be effective.

There are now some very good ‘noiseless’ pickups designed to look and sound like single‑coil types.Another option is to fit active pickups. These tend to have a lower impedance, which makes them less susceptible to induced electromagnetic interference, and their active circuitry matches the pickups to your amp or audio interface. However, many players are wary of them, partly because they need power (typically from either a 9V battery or a USB chargeable lithium battery), and partly because they may not sound the same as the passive pickups to which they’re accustomed. Also, it’s often necessary to partly disassemble the guitar to change the battery if the pickups are a retrofit. So there are pros and cons, but they can be effective.

Location, Location

Shielding a guitar’s circuitry with copper tape can sometimes help, but not as much as you might hope — the hundreds of metres of copper in the pickups are more likely to be the source of your woes!Although screening the inside of the guitar can help, if you don’t have active, traditional humbucking or noiseless pickups, it will probably make less difference than you hoped. Why? It’s simply because the half‑metre of unscreened wire linking your pickups to the controls is not the main problem: the real culprit is the several hundred metres of wire wrapped around the magnets inside your pickups, which has been configured in such a way as to respond to the smallest changes in magnetic field.

Shielding a guitar’s circuitry with copper tape can sometimes help, but not as much as you might hope — the hundreds of metres of copper in the pickups are more likely to be the source of your woes!Although screening the inside of the guitar can help, if you don’t have active, traditional humbucking or noiseless pickups, it will probably make less difference than you hoped. Why? It’s simply because the half‑metre of unscreened wire linking your pickups to the controls is not the main problem: the real culprit is the several hundred metres of wire wrapped around the magnets inside your pickups, which has been configured in such a way as to respond to the smallest changes in magnetic field.

Single‑coil pickups can be arranged to noise cancel when they’re used in pairs — they are, for example, in positions two and four of a modern Strat’s selector switch. But when used singly they’re very susceptible to stray magnetic fields, especially from mains transformers, lighting dimmers or basic wall‑wart power supplies.

It’s convenient to sit close to your computer when recording isn’t it? After all, this gives you easy access to things like your computer keyboard and your DAW’s transport controls. But sitting close to a computer often results in excessive noise pickup, even with humbuckers. The first thing to try if this is an issue is, just after hitting record, moving just a couple of metres away from the computer before you start to play. You’ll often find that your recordings then sound much cleaner than before. If they do, perhaps consider using some sort of remote control option to operate your DAW from a more distant recording position.

You may also have noticed that when the source of unwanted hum is a nearby mains transformer (for example the one in your amp), rotating your playing position also changes the level of any noise. In such cases, a common and often effective tactic is to rotate your playing position until you find a ‘null’. Experiment to find the sweet spot at which the noise is lowest, and then stick to it while you’re recording.

Earth Calling

As the name implies, a ‘grounding spike’ goes in the ground, but if that ground becomes too dry it may be the root cause of unwanted noise.For a grounding scheme to work, there should also be minimal resistance between the guitar’s ground and the mains electricity ground in the building — and a problem might not be on the guitar side of that equation. In practice, building grounds aren’t always as good as they might be. If the soil around the grounding spike dries out, for example, then the ground resistance will go up, which means any grounding‑related noise problems will likely grow worse. A simple solution to that state of affairs is to empty several buckets of water around the ground spike to moisten the soil — though note that it may take a long while for the water to soak down to the desired depth.

As the name implies, a ‘grounding spike’ goes in the ground, but if that ground becomes too dry it may be the root cause of unwanted noise.For a grounding scheme to work, there should also be minimal resistance between the guitar’s ground and the mains electricity ground in the building — and a problem might not be on the guitar side of that equation. In practice, building grounds aren’t always as good as they might be. If the soil around the grounding spike dries out, for example, then the ground resistance will go up, which means any grounding‑related noise problems will likely grow worse. A simple solution to that state of affairs is to empty several buckets of water around the ground spike to moisten the soil — though note that it may take a long while for the water to soak down to the desired depth.

Another situation I often encountered during Studio SOS visits in days gone by is where the guitar is correctly wired, the cable is of good quality and even the building ground is also fine, yet there’s still a lot of unwanted noise. This can easily occur in studio systems that are built around a laptop, in which all the connected equipment (audio interfaces, small monitors and so on) is powered using either external power supplies or two‑core mains cables, with no ground wire. If nothing is directly grounded, yet everything’s connected to each other, then the entire recording system can be left ungrounded, and that may leave you with noise problems.

Some studio systems based around a laptop and external PSUs may need to be separately grounded — something that’s easily and affordably done with an earth‑bonding plug.Thankfully, this common problem is generally very easy to fix: you just need to run a grounding wire to the mains ground from a piece of equipment that has a metal case. You can do this using a special grounding mains plug that has plastic prongs for the live and neutral connections (this avoids any nasty shocks should the ground wire get pulled accidentally out of the plug and touch the live conductor). If there’s no exposed metal to which you can connect this ground wire, you could instead ground the barrel of your guitar lead’s jack plug — the most elegant way to do this is to make up a very short cable with a jack plug at one end and a jack socket at the other so you can attach your grounding cable to the ground side of the jack socket. Put this in series with your guitar cable and it’s job done.

Some studio systems based around a laptop and external PSUs may need to be separately grounded — something that’s easily and affordably done with an earth‑bonding plug.Thankfully, this common problem is generally very easy to fix: you just need to run a grounding wire to the mains ground from a piece of equipment that has a metal case. You can do this using a special grounding mains plug that has plastic prongs for the live and neutral connections (this avoids any nasty shocks should the ground wire get pulled accidentally out of the plug and touch the live conductor). If there’s no exposed metal to which you can connect this ground wire, you could instead ground the barrel of your guitar lead’s jack plug — the most elegant way to do this is to make up a very short cable with a jack plug at one end and a jack socket at the other so you can attach your grounding cable to the ground side of the jack socket. Put this in series with your guitar cable and it’s job done.

Star Wiring Solutions

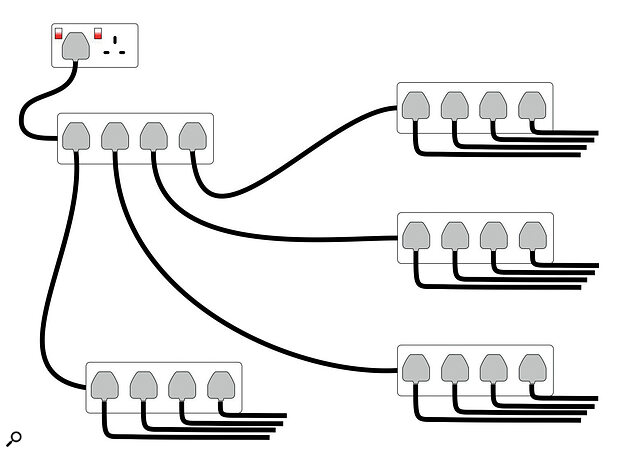

We’ve covered studio mains wiring lots of times, but it’s worth revisiting the concept of ‘star wiring’ here, because this approach reduces the likelihood of ground loops, which are yet another source of hum and buzz. Most studios, even simple home setups, require a relatively large number of power sockets, and it may seem tempting either to plug into different power points in different parts of the room, or to ‘daisy‑chain’ a number of distribution strips. But both approaches leave your system open to ground‑loop issues.

When you need to plug lots of gear in, it’s generally better to configure your distribution boards as a star, fanning out from a single socket, than to simply daisy‑chain them.

When you need to plug lots of gear in, it’s generally better to configure your distribution boards as a star, fanning out from a single socket, than to simply daisy‑chain them.

For a more detailed explanation of this, check out Hugh Robjohns’ excellent 'Ground Control' article in SOS August 2023 (https://sosm.ag/ground-control), but in practice, plugging a single distribution strip into the mains and then plugging further ones into that first strip, so that the various sockets effectively ‘fan out’ from a single point, is probably the best you can do without resorting to exotic studio wiring schemes. It’s not perfect, but it definitely reduces the risk of ground‑loop hum. (By the way, please never be tempted to remove ground connections from a mains lead to cure hum, as that increases the risk of electric shock!)

Pedal Pushing

Cheap pedal power supplies can also be a cause of problems — and the same goes for daisy‑chain power cables like the one above.Skimping on pedal power supplies can be yet another source of noise. Simple, unregulated pedal power supplies may be fine for the odd low‑current pedal, such as an analogue overdrive that isn’t too fussy about the actual voltage it runs from. But some PSUs, especially cheaper, poor‑quality switch‑mode supplies, can put noise back onto the mains — this can manifest itself as a whine (as opposed to hum or hiss) and may affect other devices plugged in close to the offending PSU. (Note that switch‑mode power supplies aren’t inherently a bad option; I’m talking specifically about cheap ones here!)

Cheap pedal power supplies can also be a cause of problems — and the same goes for daisy‑chain power cables like the one above.Skimping on pedal power supplies can be yet another source of noise. Simple, unregulated pedal power supplies may be fine for the odd low‑current pedal, such as an analogue overdrive that isn’t too fussy about the actual voltage it runs from. But some PSUs, especially cheaper, poor‑quality switch‑mode supplies, can put noise back onto the mains — this can manifest itself as a whine (as opposed to hum or hiss) and may affect other devices plugged in close to the offending PSU. (Note that switch‑mode power supplies aren’t inherently a bad option; I’m talking specifically about cheap ones here!)

In any event, you should avoid using those cheap daisy‑chain pedal power cables to supply multiple pedals from one PSU, and that’s especially the case where one or more of your stompboxes is a digital pedal. These can become noisy if sharing supplies with other pedals, even if there seems to be plenty of current available. You can recognise this by a faint whining sound in the background, and I suspect it’s because some of the digital clock noise makes it back out through the PSU. As analogue pedals require much less current than typical digital pedals and also tend to draw a consistent amount of current, they tend to be less problematic.

By far the best option is to buy a good‑quality, multi‑output regulated supply with fully isolated outputs — ideally ones that don’t share a common ground, and where each output has its own voltage regulator. These are not ‘cheap’, but relative to a big pedal collection they’re inexpensive, and they will allow your pedals to give of their best. Note, though, that some cheaper PSUs claim to have ‘isolated’ outputs but actually will only have separate output regulators and still share a common ground. With such PSUs, noise issues can still ensue, and unless you have fully isolated outputs, you can’t use a polarity invert cable to power the odd pedal that needs a pin‑positive rather than pin‑negative supply. If you use many high‑current digital pedals, then you also need to ensure that your prospective power supply can provide the requisite number of high‑current outputs!

More Gain More Pain

It’s a fact of life that most guitar players like to add a lot of gain to their signal, either when using a compressor (10dB of gain reduction typically means 10dB of make‑up gain, making any noise 10dB louder!) or when using some form of overdrive. All overdrives work by boosting the signal and then squeezing it through a circuit with deliberately limited headroom, so that the signal gets clipped. The clipping may be harsh or smooth depending on the type of pedal being used, but the more gain you pile on, the more any residual noise (including that generated by pedals earlier in the chain) will be boosted with the wanted sound.

When using a compressor, 10dB of gain reduction typically means 10dB of make‑up gain, making any noise 10dB louder!

Modern metal drive tones tend to lie at the extreme end of the gain spectrum, and you’ll find that the noise can be very significant, even when using a well‑sorted guitar fitted with humbuckers. In that scenario, using a noise gate or expander to keep pauses between notes or phrases silent may be the only solution. The only solid tip I can offer here is to place the gate/expander before any added reverb, delay or ambience. That way, the effect tails will tend to cover any unduly abrupt note endings caused by heavy gating.

Fixes In The Mix?

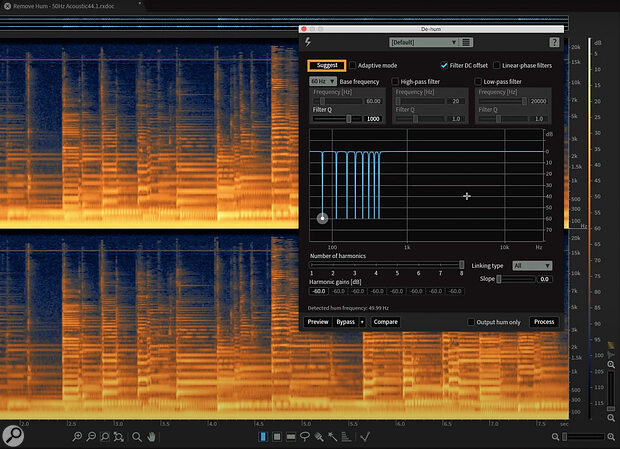

There are numerous plug‑ins that can reduce noise in recordings, and they can often produce good results as long as you have realistic expectations. If you’ve made every effort to keep your recording as free from unwanted hum and noise as possible, then they can really help to finesse the end result. To combat hum and buzz, there are plug‑ins that create very narrow notch filters at the frequencies corresponding to the local mains supply (50Hz or 60Hz, depending on which country you live in) and to the harmonics of that frequency. More elaborate ones may actually track the mains frequency. If you use these to reduce the level of hum by around 10 to 15 dB, you should find a good compromise between noise level and the tonal integrity of the overall sound.

It’s possible to use software to tackle many problem noises, such as hum (being removed here using iZotope RX), after recording, but the more you ask of such software, the more audible and unacceptable the side‑effects will become.

It’s possible to use software to tackle many problem noises, such as hum (being removed here using iZotope RX), after recording, but the more you ask of such software, the more audible and unacceptable the side‑effects will become.

It’s a similar story when it comes to broadband noise removal plug‑ins. The more basic ones need a noise‑only sample or ‘fingerprint’ to work with and only work very well if the level of noise is reasonably constant. If you’re recording yourself and plan on using this sort of processing, just make sure you record some ‘silence’ before or after your part so you have somewhere to take your noise‑only fingerprint from. Again you can claw back maybe 10dB in this way before side effects become apparent. There are some more elaborate plug‑ins that can adapt to changing noise levels but, as with gates, make sure you apply any de‑noising before adding delay‑based effects.

Obviously, that’s trickier if those effects are part of your pedal chain — if you have access to a decent re‑amping kit (ie. one that doesn’t change the sound), then it could make sense to record a clean DI signal and re‑amp it. This would allow noise gates, de‑noisers and the like to be fine‑tuned after recording. Note, though, that the effect of your pedals would still need to be audible while recording, as that affects the way you play — creating a split at the start of your chain, so that both clean and effected parts are recorded, would be a good plan. Even if the track recorded with effects isn’t used, it would serve as a reference when tweaking the re‑amped sound.

A Lot Of Noise About Nothing?

Finally, while it’s good to tackle unwanted noise at source by ensuring you have a good guitar cable and power setup, I would urge you not to stress too much about it — by which I mean, don’t feel you have to get rid of every last shred of noise. Some noise is an inherent part of the driven electric guitar sound, and in most cases it will be masked by whatever else is happening in the mix. More exposed sections can often then be treated using a combination of noise/hum reduction and level automation. It can also be helpful in the case of high‑frequency noise on a note with a long decay to automate a high‑cut filter so that it closes as the guitar note decays. Some engineers even choose to actively embrace some noise, because they find it adds a sense of energy to certain more aggressive rock styles!