Clockwise from bottom left: Unfiltered Audio Silo, Output Portal and Arturia Efx Fragments.

Clockwise from bottom left: Unfiltered Audio Silo, Output Portal and Arturia Efx Fragments.

Granular effects can be hugely powerful, but the chances of finding a preset that does exactly what you want are slim. So why not learn how to tame and tweak them?

There are numerous granular effect pedals and plug‑ins, but what exactly is granular delay? What can you expect from it, and how can you get it under control in your compositions and mixes? In this article, I’ll answer those questions, but since the scope of the sounds you can create with this type of effect is so broad, I’ve also created some audio examples to demonstrate the possibilities.

At its core, a granular delay stores audio into a temporary buffer, just as a conventional delay does, but then it breaks down the input signal into short sections that we call ‘grains’. These grains can be anything from a few milliseconds to several hundred milliseconds in length, but the real trick is that the individual grains can be processed in different ways before being sent to the output. Depending on the grain length and the types of processing applied to the individual grains (the most common are pitch‑shifting, reversal, time‑stretching and/or re‑ordering, sometimes with a random element applied), the effect produced can be anything from glitchy chaos to rich, evolving soundscapes.

Key Parameters

A typical granular delay will, of course, include the sort of controls you’d commonly find on a regular delay pedal or plug‑in (specifically delay time and wet/dry mix, along with a feedback control to recirculate the repeats) but you’ll also find a Grain Size control that determines the length of each grain. Smaller grains can be stretched and overlapped to produce smooth, textural effects, or they can be used to create glitchy effects. Longer grains can also be stretched and overlapped to produce flowing soundscapes, but they can also be used more overtly to produce rhythmic effects.

A Grain Density control will adjust the number of grains that are generated per second: the higher the density, the more likely it is that result will sound smooth and flowing, whereas low grain densities can create a variety of effects, from stutter repeats and glitches to crystalline jangles and sparkles if combined with pitch‑shifting.

There will usually be a pitch‑shift control too, which adjusts the pitch of individual grains. The most musically pleasing intervals will be octaves, fourths and fifths, but modest pitch detuning can also be useful. If applied using a randomiser, individual grains will appear at different pitches, which is an effect that can make for interesting ear candy if not pushed too high in the mix. Such effects often benefit from a separate reverb being added after the granular processing — some granular plug‑ins have this feature built in, but it’s easy enough to place a reverb plug‑in or pedal directly after the granular delay.

Time‑stretching is a similar process to pitch‑shifting, except that now the grains will play back at their original pitch while their length is adjusted by stretching or compressing them in time. Time‑stretching is a good means of fine‑tuning the grains’ overlaps, so that they produce a more continuous sound, but if you need to achieve something more glitchy, you can use it to shorten the grains.

Feedback usually works in the expected way: you set how much of the delayed signal is fed back into the input of the delay line to generate repeating echoes. But in a granular delay the output has been subjected to granular processing, and when it goes back through the delay buffer a second time it is processed again, adding further to the complexity of the effect. The higher the feedback level, the more repeats are generated and the more texturally complex the delays become.

Red Panda Particle 2 pedal.Most granular delay effects include the option to dial in an element of randomness. This might be used, for example, to adjust the probability of a grain being played forwards or in reverse, or of it being subjected to a specific interval of pitch‑shifting. Randomisation might also be set to adjust the grain size or even to mix up the order in which grains are sent to the output. The inherent unpredictability just adds to the organic complexity of the effect while, at the same time, taking away any sense of repetition.

Red Panda Particle 2 pedal.Most granular delay effects include the option to dial in an element of randomness. This might be used, for example, to adjust the probability of a grain being played forwards or in reverse, or of it being subjected to a specific interval of pitch‑shifting. Randomisation might also be set to adjust the grain size or even to mix up the order in which grains are sent to the output. The inherent unpredictability just adds to the organic complexity of the effect while, at the same time, taking away any sense of repetition.

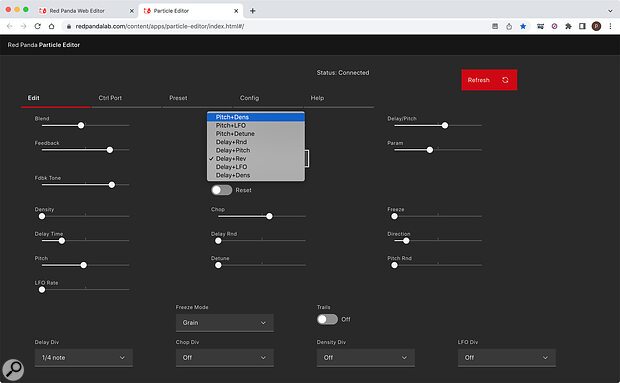

Given the number of parameters at play, it’s perhaps not surprising that granular delay pedals often don’t allow you to control all of them all of the time, but they can be powerful effects all the same. For example, Red Panda’s Particle 2 has a rotary switch that lets you choose whether the effects will be based on pitch, reverse, detuning or LFO modulation, and also has a Freeze mode where the buffer loops indefinitely until an input is received that is loud enough to retrigger it and start the capture cycle all over again.

The Red Panda Particle 2: a granular delay pedal with some clever features and this web‑based software editor.

The Red Panda Particle 2: a granular delay pedal with some clever features and this web‑based software editor.

By contrast, plug‑ins such as Output’s Portal, Arturia’s Efx Fragments or Unfiltered Audio’s Silo (shown in the header screenshot) may have additional controls to add even more complexity to the end result, though the key parameters are the same in all of them. The types of extra you might see are modulation sources, controls to set the probability of random events occurring, additional reverb stages, filtering and sometimes grain shape. Using grain shapes that fade in and out rather than just starting and stopping where they were chopped helps smooth out the effect if that’s what you need. It is always worth exploring the presets and then looking at the control settings to see how those effects were achieved.

Granular Adventures

Whether the source you start with is a guitar, a synth or even a voice — pretty much anything, in fact — If you need an ambient soundscape, granular processing can definitely deliver it. Long grain sizes combined with a high density and generous time‑stretching will generate smooth, evolving soundscapes that work very well when applied to pad and drone sounds, and such settings can also often turn ‘found sound’ recordings of random sources into musically useful effects.

If you lean more towards unsettling, glitchy sounds, you’ll find what you’re looking for by using short grains at lower densities.

If you lean more towards unsettling, glitchy sounds, you’ll find what you’re looking for by using short grains at lower densities. That way, each grain is heard as an individual event rather than being blurred into a continuous stream — then maybe add some random pitch‑shifting for a spot of granular chaos as grains pop out at a different pitches. Alternatively, when combined with pitch‑shifting and feedback, but without any timing randomisation, the effect can be more solidly rhythmic; such glitchy, stuttery effects can sit very comfortably in some dance and electronica genres. I particularly like the effect of adding randomised pitch‑shifting and grain reversal (but still sticking with octaves, fourths and fifths, so as to maintain some semblance of musicality!), as this can add harmonic complexity and a sense of movement to pads, melody lines or percussion parts.

Where parameter automation is available (it is in most plug‑ins), you can use this to adjust the grain size and feedback in a way that syncs with the DAW project’s tempo — this can be a great way to spice up drum loops or other parts while still maintaining a sense of rhythm that works with your project.

Creative Excess?

Once you have your head around the basics of granular delays, you can get a bit more experimental. For example, you can take things in a seriously crazy direction by feeding one granular pedal or plug‑in into another. But an equally valid approach — and one that’s often more useful in practice — is to use these effects in parallel, building up a composition from simple layers and applying a different granular process to each one. For example, applying a textural granular delay to a vocal or guitar part can turn it into something that’s unrecognisable but still musical. Run this alongside a track carrying the same sound (or a related part) but treated with a more sparse granular effect, and you can create something that sounds absolutely huge.

You do need to give yourself plenty of time to experiment, because even with a pedal that has few physical controls, such as the aforementioned Particle 2 or the Walrus Audio Fable, the interaction between the different controls will cause the character of the effect to change in ways that may surprise you, even if you’re only making relatively small adjustments. As I said above, with plug‑ins there’s often more in the way of controllability, but it pays to start out with the basic parameters first to see how they interact before you take on the more esoteric features that a particular plug‑in might offer.