Few have contributed as much to the technology behind rock & roll as Charlie Watkins and his company, WEM. We celebrate the life of one of audio’s great inventors.

Look closely at the video of Stones In The Park and there, among the Hell’s Angels, Mick Jagger in his frock, Keith Richards looking... like Keith Richards, and an audience the size of which had never before been seen in London’s Hyde Park, occasionally you’ll catch a glimpse of a small, balding man looking completely out of place. That was Charlie Watkins, who died in October 2014, aged 91, at his home in South East London. Without Charlie (and he was always Charlie, never ‘Mr Watkins’), that gig could not have taken place. Neither could the seminal Windsor Jazz & Blues festival in 1967, nor Jimi Hendrix’s and the Who’s era–defining performances at the Isle Of Wight festival in 1970, nor many, many other performances from artists as diverse as Tony Bennett, the Byrds, Cream and Pink Floyd. In fact you could make a good case for Charlie Watkins having made certain kinds of live music performance possible, and for his being the spiritual father of today’s festival scene. No Charlie, no modern PA in the 1970s. No modern PA, certainly no Pink Floyd gigs!

Charlie Watkins, creator of the Watkins Electric Music company — WEM as it was branded — provided the power for them all, and in the process more or less invented the modern PA system. Portable audio mixers, slave amps, foldback: WEM could lay claim to have invented them all.

Ship To Shore

Born in the East End of London in 1923, the odds weren’t good that Charlie Watkins would even survive the war that was to break out 16 years later. In 1938, at the age of 15, he joined the Merchant Navy and, having had a bare few weeks training, spent the following years criss–crossing the Atlantic in unarmed convoys. With a survival rate of just one in four, the unsung heroes of the Merchant Navy had everything stacked against them, but somehow Charlie survived the torpedoes and bombs and managed, in passing, to develop a love affair with the accordion, which would last until his death. He also experienced first–hand the trials of fellow shipmates who were guitarists and struggled to make themselves heard — something he was to encounter again once the war was finally over, when he earned his living for a few years as a professional accordionist.

Seeking some sort of financial stability, in 1949 Charlie opened his first shop, in Tooting Market, London, with his brother Reg. At first they sold records, but by 1951, they had moved to Balham and began selling musical instruments — though few guitars, as the instrument was still largely unknown by the public and was disparagingly referred to as a ‘banjo’ by all and sundry. Things changed rapidly, twice. First, Bill Haley introduced the world to rock & roll.Then, in 1957, Lonnie Donegan ushered in the short–lived but incalculably influential skiffle boom, which inspired the generation that produced the Beatles and everything that flowed out of that phenomenon.

Free at the 1970 Isle Of Wight Festival, mixed on WEM Audiomasters and playing through the Who’s WEM column speakers.Photo: Charles Everest /www.CameronLife.co.uk

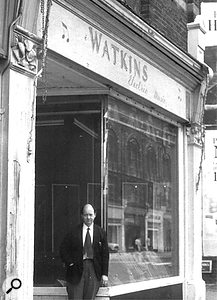

Free at the 1970 Isle Of Wight Festival, mixed on WEM Audiomasters and playing through the Who’s WEM column speakers.Photo: Charles Everest /www.CameronLife.co.uk Charlie Watkins outside his first shop in Balham.

Charlie Watkins outside his first shop in Balham. Charlie in his later days, playing his much–loved accordion.While Reg was more interested in the records, Charlie had the instrument bug, and was soon selling all the guitars he could get to satisfy the insatiable demand. American equipment was unobtainable due to currency restrictions, so sources of anything that could be described as a guitar were found across Europe, and Watkins’ shop became one of a handful of places were the highly prized instruments, not to mention Charlie’s early amplifiers, were sold.

Charlie in his later days, playing his much–loved accordion.While Reg was more interested in the records, Charlie had the instrument bug, and was soon selling all the guitars he could get to satisfy the insatiable demand. American equipment was unobtainable due to currency restrictions, so sources of anything that could be described as a guitar were found across Europe, and Watkins’ shop became one of a handful of places were the highly prized instruments, not to mention Charlie’s early amplifiers, were sold.

Early Amps

In a previously unpublished, in-depth interview given towards the end of his life, Charlie told me: “Guys used to come in with Hawaiian guitars with the idea of joining a band, and when I did gigs with a band, it was lovely to have a guitar, but you could never hear them. So instead of a guitar player, people would hire a saxophone player, and I thought ‘I’ve put up with that long enough, I can do something about that. I’ll make an amplifier.’ Selmer sold a Truvoice contact–mic pickup that you could stick under the bridge, and they were only about three quid, so I went up to Tottenham Court Road and bought these amplifiers — just power amps — and I thought I could find somebody to make a preamp for me. A guy I spoke to in the shop, Arthur O’Brien, was interested in guitars and in what I was doing, and I told him what I was looking for. He finished up in my shop, because he was good at electronics and he could do what I wanted, so we got one going and it sounded marvellous — it was about 4 Watts. We made 20 and sold them.”

Life in post–war England was rarely that straightforward, however, as Charlie recalled: “This was in the old days and they were still on AC/DC — you could get killed easily with electricity back then and I got some terrible shocks in my time.” The problem was that musicians didn’t know which they were going to find at the venue: AC or DC. Some just plugged in and hoped for the best.

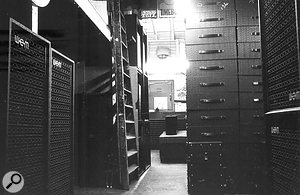

The WEM factory in Offley Road.“One day I heard that somebody had been killed by an amplifier, and I decided I wasn’t happy. I decided to get back all the ones that we’d sold. They had two–pin plugs on them, and if you put it in the wrong way and got the polarity wrong you had 240 Volts up your nose! People were dying like flies in those days, especially down in Battersea, where they were still using DC. Anyway, we got them back and made ordinary AC amplifiers that were safer, and got a bigger power unit and put them in grey, square boxes. Guys were coming in, plugging their guitars in and they loved them. I wasn’t a manufacturer then, I was still just a shopkeeper, but with a Black & Decker in the back room.”

The WEM factory in Offley Road.“One day I heard that somebody had been killed by an amplifier, and I decided I wasn’t happy. I decided to get back all the ones that we’d sold. They had two–pin plugs on them, and if you put it in the wrong way and got the polarity wrong you had 240 Volts up your nose! People were dying like flies in those days, especially down in Battersea, where they were still using DC. Anyway, we got them back and made ordinary AC amplifiers that were safer, and got a bigger power unit and put them in grey, square boxes. Guys were coming in, plugging their guitars in and they loved them. I wasn’t a manufacturer then, I was still just a shopkeeper, but with a Black & Decker in the back room.”

The WEM factory in Offley Road.Nonetheless, Charlie’s amplifiers quickly became the mainstay of the early British ‘Beat Boom’, along with rivals from Selmer and Vox. In 1954 Watkins had launched the Westminster, and he followed that with the novel, V–fronted Dominator — angled, he said, to help project the sound better into an audience.

The WEM factory in Offley Road.Nonetheless, Charlie’s amplifiers quickly became the mainstay of the early British ‘Beat Boom’, along with rivals from Selmer and Vox. In 1954 Watkins had launched the Westminster, and he followed that with the novel, V–fronted Dominator — angled, he said, to help project the sound better into an audience.

Echo Vocation

But it was the 1958 Copicat tape echo that was to be WEM’s first major success. Picked up by Johnny Kidd’s guitarist, Joe Moretti, and heard to devastating effect on Kidd’s hit ‘Shakin’ All Over’, it made echo the first ‘must–have’ guitar effect in history. Skiffle had faded as fast as it had emerged, leaving Charlie with a business gap to fill — and a sound in his head. That sound was echo, first made internationally famous by the Italian performer Marino Marini, who had a string of hits in the 1950s and ‘60s. Marini’s echo was derived from the tape–loop–between–two-Revoxes method, which was hardly practical on stage (though some tried). What was needed was a simple box that could deliver the goods at an affordable price. Enter the Copicat tape echo, designed by a new recruit to WEM: Bill Purkiss.

Though Watkins never trained as an engineer and certainly never claimed to be one, what he was was a backroom tinkerer and inventor in an almost Victorian mould. It was Charlie who insisted a tape loop was the way to go and it was Bill Purkiss who turned Charlie’s idea into reality. “Something I learned then is that when you’ve got a new bloke on the staff, a boffin, grab him while he’s new, because he’ll churn out all the stuff he’s had in the back of his mind for years. But after six months everything slows down and they start telling you you mustn’t rush things. The last boffin I had took two years just to redesign the Copicat for me, but Bill Purkiss designed the whole thing from scratch in just three months!” Watkins sold his first 100 Copicats in a single day.

The WEM factory in Offley Road.Almost in passing, Watkins had also launched the second solid-bodied guitar ever produced in the UK (the first was the Dallas Tuxedo). It was dubbed the Rapier and was designed by Charlie’s brother, Reg, who was working with another brother, Syd Watkins, manufacturing them in a factory in Chertsey, Surrey. Strat–like in shape, the handmade Rapiers came in 22, 33 and 44 versions (the numbers referred to the two, three or four pickups on offer) and, like Charlie’s amplifiers, they became the staple of thousands of young British guitarists in the early 1960s. Even by the standards of the time they weren’t particularly expensive (between £20 and £30), and though they’ve never approached Fender-like values, they are still sought after by nostalgic collectors, as are the Watkins amplifiers and Copicats.

The WEM factory in Offley Road.Almost in passing, Watkins had also launched the second solid-bodied guitar ever produced in the UK (the first was the Dallas Tuxedo). It was dubbed the Rapier and was designed by Charlie’s brother, Reg, who was working with another brother, Syd Watkins, manufacturing them in a factory in Chertsey, Surrey. Strat–like in shape, the handmade Rapiers came in 22, 33 and 44 versions (the numbers referred to the two, three or four pickups on offer) and, like Charlie’s amplifiers, they became the staple of thousands of young British guitarists in the early 1960s. Even by the standards of the time they weren’t particularly expensive (between £20 and £30), and though they’ve never approached Fender-like values, they are still sought after by nostalgic collectors, as are the Watkins amplifiers and Copicats.

Beat Combos

If guitars and amplifiers were primitive in the early 1960s, PA systems were out of the Dark Ages. Few artists owned them, and hire companies were more or less unheard of. If you were an amateur musician you plugged everything — vocals, guitars and bass — into a single combo and hoped for the best (ever wondered why a Vox AC30 has so many inputs?), while if you were a touring professional, you relied on whatever house PAs were to be found in the venues you were playing. ‘Atrocious’, ‘dangerous’, ‘inaudible’ and ‘army surplus’ are just some of the words that describe what was to be found on the UK circuit at the time!

Inevitably, musicians looked for something better. Gradually, the same companies that offered rapidly improving backline products, like the Vox AC15 and AC30 and Selmer’s Zodiacs, also began to offer ‘mixer amps’ and small speaker columns. These usually contained 8–, 10– and even 12–inch speakers, only nominally designed to handle anything more than the frequency range of a guitar. Even as late as the mid-1960s, when the Beatles and the Rolling Stones were trying to play venues crammed with hysterical, screaming fans, they were forced to rely on a single pair of Vox columns at the side of the stage. It was all that was on hand for amplification — and it was reserved solely for vocal duties.

The WEM factory in Offley Road.The man who changed that was Charlie Watkins. In 1961, he had managed to buy his first factory: the building in Offley Road that was to become a regular haunt for a generation of musicians who included David Bowie, Jimi Hendrix, Marc Bolan and many others. It was also where modern PA was created, somewhat after the manner of Frankenstein’s monster.

The WEM factory in Offley Road.The man who changed that was Charlie Watkins. In 1961, he had managed to buy his first factory: the building in Offley Road that was to become a regular haunt for a generation of musicians who included David Bowie, Jimi Hendrix, Marc Bolan and many others. It was also where modern PA was created, somewhat after the manner of Frankenstein’s monster.

“I think it began when I went down to the Wimbledon Palais one night to see Johnny Kidd and the Pirates,” he recalled. “That started me going out to see what was being played, rather than just sitting in the office, and wherever I went, it was like encountering an old enemy — you couldn’t hear the singer. All there was was this dreadful PA at the time. There were no foldback monitors, just a guy with a Shure Unidyne or an old Reslo ribbon mic and a hopeless PA system. The Beatles used the old Vox 4x10 and so I went one better by making a 6x8 which folded in half, but I had a 4x10 as well because I thought — like everyone else — well, that’s what PA was!

“The biggest laugh of all was the house PA that artists often had to use. They had these line–source systems and they were bloody awful — they were terrible! It was usually horrible old war-surplus equipment with 12–inch hard–cone speakers with boxes spread all round the hall. I don’t know why it went on so long.

Fleetwood Mac’s first ever performance was at the 1967 Windsor Jazz & Blues Festival, which was mixed using the first Audiomaster mixer ever made.”Of course, by the mid-‘60s, guitarists had started to get decent amplifiers, but the main thing that audiences wanted to hear was the voice — they wanted to hear Mick Jagger and Rod Stewart, not the guitar all night.”

Fleetwood Mac’s first ever performance was at the 1967 Windsor Jazz & Blues Festival, which was mixed using the first Audiomaster mixer ever made.”Of course, by the mid-‘60s, guitarists had started to get decent amplifiers, but the main thing that audiences wanted to hear was the voice — they wanted to hear Mick Jagger and Rod Stewart, not the guitar all night.”

A PA Is Born

Ironically, it wasn’t the home–grown Beatles or Stones who changed things, but American group the Byrds.

“In 1965, when ‘Mr Tambourine Man’ came out, the Byrds were coming over and they didn’t want the sort of rotten PA everyone was using. I don’t know what they’d been using in America, but it was probably pretty much as bad as it was here and they didn’t want to bring W–bins over with them. So their tour promoter called me and said, ‘For £100 I’ll let you build a PA for the Byrds.’ It seemed like a good idea to me at the time. I could do with getting into the PA market.

“I had a 60 Watt germanium–transistor amplifier, I had a 30 Watt valve amplifier, I had my 6x8 folding column, 4x10s, 2x12s, but all the speakers you could buy then were called ‘all-purpose’, which just meant the manufacturer could sell the same speaker for absolutely everything. None of them were any good for the human voice.

“So, off we went on tour with the Byrds. I think the first gig was at the Orchid Ballroom, in Purley. I couldn’t go for some reason, but the next morning... Well, if there had been a big hole, I’d have crawled into it! Crosby was on the phone saying ‘expletive deleted rubbish!’ So I went out with them the next night to see what was wrong and the moment they started up ‘Mr Tambourine Man’ it was obvious they were right — you couldn’t hear a word. Anyway, McGuinn took me aside and said, ‘Can I talk to you?’ I said, ‘OK, I know, I’ve got it wrong and I’ll try to get it right’. So that day I went down to Tannoy, who used to be down in West Norwood. They were brilliant, brilliant people. I bought two of their great 4x12 columns, got some more of my 30 Watt valve amps and, I admit it, I bodged together a system. I was as bad as anyone else in those days — possibly even a little bit worse, because my rubbish wasn’t 100 Watts, it was only 30 Watts!

“Before he went home, McGuinn phoned me and he said, ‘Charlie, I would be obliged if you wouldn’t say we endorsed the gear, because I can’t really do that, but I just want to thank you for trying to help us.’ And I thought to myself, well, this PA thing is harder than it seems, but I want to do it even more now after all that trouble!”

The story had a happy ending. Some years later, Charlie received another phone call. “They came back to Europe, went to Holland first and got a lot of money — enough to buy a WEM PA. Roger called me to see if we could help. I was so pleased, I’d have given them a PA, but they said they were coming to see me and asked if there was anything they could bring back. So I said, ‘Yes some Dutch cheese, please.’

“Anyway, they came over to the office, I made some coffee and we sat there drinking coffee and eating this cheese, while they ordered a 1500 Watt system to do their tour. They asked how much is it, and I think it was about £4000 — this must have been 1968 — so Roger opened this great big bag he had with him, took a tea towel out, and there was this amazing collection inside: Dutch money, German money, pound notes, all wrapped up in a tea towel! We had to sit there and work it all out to get the money right! Anyway they got their system and ended up taking it back to the States.”

Slaving Away

The Byrds had returned to Watkins because word was spreading that Charlie had made a major breakthrough, and he had: the mixer-to-power-amp-to-speaker arrangement that still figures in most contemporary PA systems.

“One day I went to Belgium to see our distributor, and with him was our French man. The Belgian guy was very clever at electronics and the French guy was very thoughtful about music. We sat in a restaurant until the early hours and I was telling them of the situation in Britain, and I said I was looking for a way of getting an amplifier that could be added to other amplifiers. That night, the three of us hatched the idea for the slave amplifier.

The Watkins Rapier was only the second electric guitar to be mass–produced in the UK.“When I got home and said I wanted to try this, I got the usual reaction you always get from boffins: ‘No, no it can’t be done.’ But in the end, Norman Sergeant, who was working for me, realised it could be done. I said I didn’t want a guitar sound, I wanted something more like a hi–fi sound with a flat response, and Norman said we should use a transistor amplifier, which we did. He based it on a standard RCA design, which he modified to suit our ideas, and that became the original SL100.

The Watkins Rapier was only the second electric guitar to be mass–produced in the UK.“When I got home and said I wanted to try this, I got the usual reaction you always get from boffins: ‘No, no it can’t be done.’ But in the end, Norman Sergeant, who was working for me, realised it could be done. I said I didn’t want a guitar sound, I wanted something more like a hi–fi sound with a flat response, and Norman said we should use a transistor amplifier, which we did. He based it on a standard RCA design, which he modified to suit our ideas, and that became the original SL100.

“Then I got in touch with Goodmans. They had a speaker called the Axiom 301, with a concentric cone. All the other things that they were offering to the likes of me were general-purpose with horrible stiff cones. That was what made the difference; for vocals you needed gentle cones that, when you touched them, they moved easily, not like the horrible stiff things they were using for guitar speakers. Another thing I knew was that you needed a speaker with a decent hefty magnet, and I’d always had that with Goodmans and Celestion, not like those dreadful Jensen things they had in America — you couldn’t get any balls out of them.

“The other jewel in what was left of my crown at the time was a brilliant guy called John Thompson, who used to work in the evenings at the Marquee, doing security. He was a really intelligent guy, but very hefty. I had been bitten by this new bug now. I’d seen over the mountain with this new system, using Norman Sergeant’s new amplifier and these soft–coned speakers in a proper box, and I could see the business was there for the taking. I was talking to John about it one day and I said to him that I’d like to put a PA system together that was louder than everybody else’s — Vox, Truvoice... all the others.

“Harold Pendelton, who owned the Marquee Club, also ran the famous Jazz & Blues festival at Windsor, which had jazz players playing to an audience of just three or four hundred. He couldn’t have had a bigger audience, because nobody could have heard them. So I said to John, ‘Tell him I’ll put a 1000 Watt system together!’ That was completely unheard of at the time. He said, ‘OK, if you’re serious, I’ll see what he thinks’.

The Watkins Dominator, with its distinctive V–shaped cabinet, intended to better project the sound of an electric guitar into an audience. “So John told him and Harold Pendelton, being no fool, screwed me down to doing it for nothing and warned me that if it went wrong it was going to be entirely my fault. To be honest, I felt it was my last shot. If it went wrong it would have been commercial suicide. We made up a stack of gear, got it going in the factory with half a dozen of these new SL100 slave amps. At first we set up 100 Watts, with a pair of columns with four twin–cone speakers each. That was going nicely and when you spoke through it, it sounded natural. Then we plugged another pair in, so it wasn’t twice as loud, but maybe a third louder. When we got to the third amp, one of the Axiom 301s started walking along the overhead shelf and fell on the works manager, Gordon Shepherd’s, head, nearly knocking him out! It wasn’t very nice for him, but it was getting pretty loud and I thought: I’ve got something right here.

The Watkins Dominator, with its distinctive V–shaped cabinet, intended to better project the sound of an electric guitar into an audience. “So John told him and Harold Pendelton, being no fool, screwed me down to doing it for nothing and warned me that if it went wrong it was going to be entirely my fault. To be honest, I felt it was my last shot. If it went wrong it would have been commercial suicide. We made up a stack of gear, got it going in the factory with half a dozen of these new SL100 slave amps. At first we set up 100 Watts, with a pair of columns with four twin–cone speakers each. That was going nicely and when you spoke through it, it sounded natural. Then we plugged another pair in, so it wasn’t twice as loud, but maybe a third louder. When we got to the third amp, one of the Axiom 301s started walking along the overhead shelf and fell on the works manager, Gordon Shepherd’s, head, nearly knocking him out! It wasn’t very nice for him, but it was getting pretty loud and I thought: I’ve got something right here.

“When it got to 500 Watts, we had the police knocking on the front door and one of the girls from upstairs came down crying that there was this terrifying movement in the building. You see, nobody had ever heard anything like it. We’re used to it today, but nobody had heard anything like that before — well, except for Hitler at Nuremberg. He did even better than me!”

Watkins had doubled that to a (then) seemingly impossible 1000 Watts, just in time for the 1967 Windsor gig.

The WEM Audiomaster

The PA mixer, meanwhile, had also finally struggled into being, having been taking shape rather more sedately in Charlie’s mind since as long ago as 1963: “When you’re in a firm like mine, if you’re not technical yourself, which I’m not, you rely heavily on your technicians and you have to follow them — you must not transgress into their area. Everybody wants to grab their area, and at times I was like a stranger in my own works because of this. Years before I’d wanted a mixer, and I had three or four boffins working for me then, but the way it was, I felt I had to present it to them and almost ask their permission or approval for what I wanted to do. I remember the day. I’d made a wooden, leathercloth–covered mock–up of what I wanted — I called it Fred — and the peals of laughter that greeted it, you wouldn’t believe!

An early valve–based WEM Copicat and a later, solid–state MkIV version (top).“When this became feasible, this PA that I called my wall of sound, the mixer reared its head again. So I got Fred out of the coal cellar and took it to a technical firm of boffins — I had to take it outside my own company to get it developed! I knew exactly what I wanted: a lot of EQ, not just one knob that does everything, and an output to feed my slaves. They did it in three parts and I brought it back to my place, where they condescended to finish it. That was the first Audiomaster. It would have cost you £65 the day it was launched.

An early valve–based WEM Copicat and a later, solid–state MkIV version (top).“When this became feasible, this PA that I called my wall of sound, the mixer reared its head again. So I got Fred out of the coal cellar and took it to a technical firm of boffins — I had to take it outside my own company to get it developed! I knew exactly what I wanted: a lot of EQ, not just one knob that does everything, and an output to feed my slaves. They did it in three parts and I brought it back to my place, where they condescended to finish it. That was the first Audiomaster. It would have cost you £65 the day it was launched.

”When it got to the great day at Windsor, August 1967, we realised the mixer didn’t have any input sensitivity control, and some of those rock singers... Well, they’d just stick a microphone down their throats and scream. And guess what? There was the Crazy World Of Arthur Brown, top of the bill! Then you’d get someone like Melanie, or Joan Baez, who’d stand half a mile from the mic and whisper, and we couldn’t cope, because we had no way of controlling the sensitivity. So Norman Sergeant went down to an electric shop in Windsor, bought the parts and wired it up in the field! And it worked — we could control the input!

“So, the evening started, and I forget a lot of those who were on... Well, except there was this little new band playing their first gig — Fleetwood Mac, they were called — and there was also Ten Years After. They were marvellous! We started to build the power slowly up. 500 Watts, 600 Watts... I was expecting something to go wrong but it didn’t. It sounded lovely! Then Arthur Brown came on, topping the bill, and I said, ‘When he does his scream in ‘Fire’, put it on full everything — the lot; full power, full reverb.’ I can hear that scream now! It was amazing! No one had ever heard a sound like it! It was only 1000 Watts and you’d use more than that on your foldback now, but at the time nobody had ever heard anything like it!

The hugely popular WEM Festival PA stack.“But shortly after that scream, I felt a hand on my shoulder and heard the words: ‘I must ask you to accompany me to the police station.’ There he was, this policeman, with the Lord Mayor in all his robes, the residents’ committee, the Noise Abatement Society... It was bloody ridiculous, particularly as there were people leaning out of the houses nearby, cheering and waving! So I said, ‘All right, but you’ll have to let me talk to my people and tell them to switch the sound system off.’

The hugely popular WEM Festival PA stack.“But shortly after that scream, I felt a hand on my shoulder and heard the words: ‘I must ask you to accompany me to the police station.’ There he was, this policeman, with the Lord Mayor in all his robes, the residents’ committee, the Noise Abatement Society... It was bloody ridiculous, particularly as there were people leaning out of the houses nearby, cheering and waving! So I said, ‘All right, but you’ll have to let me talk to my people and tell them to switch the sound system off.’

“‘What you talking about, switch it off?’ he said. And I said, ‘Well, I’m not going to let them use it if I’m not here.’ He was no fool! He knew quite well what I was getting at. If we’d switched the sound off, he’d have had 30 or 40 thousand bloody madmen going through his precious borough, smashing it up, so he said: ‘Perhaps we can make some sort of other arrangement...’

“They took me to court for it, too — but I won. They were standing in the way of progress and it was ridiculous. A thousand Watts? People have 1000 Watts at home now and nobody thinks anything about it!”

Perhaps the most amusing aspect to the court case was that Charlie was defended by none other than the Right Honourable Quintin Hogg, later to be Lord Chancellor and a doyen of the Conservative Party. He must have been pretty good at his job, though, as the case was dismissed out of hand.

It’s Only Rock & Roll...

Why did Charlie do it? “Well, it wasn’t for love of rock & roll! It wasn’t that I wanted to be up there on stage being a singer — I didn’t want your bloody rock & roll anyway, I never did like it and I don’t like it now! I just wanted to do what I wanted to do, which was do something to curb a terrible error that was going on in the world of music. It was a challenge and it became a bit of an obsession.”

Windsor also saw the debut of columns being used as stage monitors: “I think what they did was use a PA as a sidefill — it wasn’t really a monitor because it was uncontrollable. The slaves then didn’t have volume controls on them; that came later when proper monitoring started, so as to let people control the feedback level. But no one used to buy them. If they had more money, they’d use it to put up more PA, and that was my next bone of contention, with Family.”

The Wedge Of Reason

“After Windsor, which decided it didn’t want to put up with the likes of me there again, Harold Pendleton started putting on festivals at Plumpton, I think it was, and came up with the idea of having a main stage for the big bands, plus other bands playing in a marquee — just like they do at festivals now, of course. Well, I went down there and set up a system in the marquee, and it was John Thompson who did the sound. We’d set it up and taken a cable from the Audiomaster headphone socket to a 1x12, so that I could hear if everything was going all right.

“Savoy Brown were on one night and playing away, and Roger Chapman [of Family] came on, gesturing that he couldn’t hear himself. He wasn’t alone — the stages were full of singers always making gestures that they couldn’t hear themselves, it was a real problem. Anyway, Roger heard there was sound coming from the side of the stage, which was where we used to mix from in those days, not from the front like they do now. Roger heard that sound and he thought it was him, so he grabbed the speaker. What a look of disappointment when he heard Savoy Brown coming out of it instead of him! And you had to be careful with Roger or you’d pretty soon get a mic stand over the head! Anyway, he more or less threw it at me, but I thought, ‘Well, if I can get from that Audiomaster into an amplifier...’ And that was it. So I did that and he was delighted — he went berserk! He always used to perform with a towel, because he used to sweat a lot, so when I gave him the 1x12 monitor, he rolled up the towel, stuck it underneath, and hey presto, there you go — a wedge monitor for the first time!

The WEM Audiomaster PA mixer.Photo: Melmusic“We found that made an amazing difference in the performance of a band. Hardly anything made as much difference, though sidefills were very important too. A sidefill would give everybody everything.”

The WEM Audiomaster PA mixer.Photo: Melmusic“We found that made an amazing difference in the performance of a band. Hardly anything made as much difference, though sidefills were very important too. A sidefill would give everybody everything.”

Windsor was a turning point for the entire concept of festivals — and, of course, for WEM’s fortunes. “Once again, there was a queue outside my factory on the Monday morning — Rod Stewart and the Faces, Jon Hiseman and Arthur Brown... He had four of those cheaper columns, because he was broke, but he didn’t stay broke for long! He was so pleased with the sound at Windsor that he sat there behind the stage and wrote a poem about the advent of WEM PA and he gave it to me. I wish I still had it!

“From then, it got into an arms race. If Arthur Brown had 200 Watts, the Faces would say ‘Right, Charlie, we want 300 Watts.’ Then the Floyd would come along and say, ‘Right, we’ll have 500 Watts.’ I’d be out three or four times a week in those days and learning so fast. The festivals were hard because you had to sleep in the truck, it was all night, and if I’d developed something new or put different speakers in, trying something out and it didn’t work, well, people would go crazy. I got hit by a bottle once and that put me off. But it’s a good way to learn — it’s no good sitting in your office and getting reports from people.’

Make A Dish

So, what experiments was he trying? “One very interesting one came about in an odd way. My mother used to live in Weybridge, and on my way back from seeing her I used to come back through Brooklands, and there was Plessey or Phillips or someone, and in their window they had a model of one of these big towers with a parabolic dish, and I thought, ‘That’s the way to go!’ Then I was in Greece on holiday and I went to an amphitheatre and it had the same shape — the same idea. So I made a fibreglass parabole, an enormous thing, and we took it to the Isle Of Wight Festival. But the problem was the only 10–inch speaker I could get to drive it was a 10 Watt speaker, and when I tested the 10 Watts, I could hear this lovely, lovely sound — it was a better sound than my PA — but it didn’t have the power. It was impossible to get speakers with a good sound and high power at the time. Gauss had come out with a speaker that was supposed to handle 200 Watts, but it had a lousy sound because of a hard cone. Once you take the movement out of the cone, you lose that sound.”

The Rolling Stones at Hyde Park.The essence of WEM’s success was that they had taken a clear lead, and not just with early Audiomaster mixers and experiments with various speakers and configurations; they had also finally made successful transistor amplifiers that could be slaved, ran (relatively) cool and were, by the standards of the day, reliable. Just as rock music had suddenly started to take itself seriously and desperately needed its lyrical content to be heard and understood, along came Charlie Watkins with a system that made it possible. A bit of distorted sound may not have marred the impact of the early Rolling Stones, but Pink Floyd or the Moody Blues were another matter.

The Rolling Stones at Hyde Park.The essence of WEM’s success was that they had taken a clear lead, and not just with early Audiomaster mixers and experiments with various speakers and configurations; they had also finally made successful transistor amplifiers that could be slaved, ran (relatively) cool and were, by the standards of the day, reliable. Just as rock music had suddenly started to take itself seriously and desperately needed its lyrical content to be heard and understood, along came Charlie Watkins with a system that made it possible. A bit of distorted sound may not have marred the impact of the early Rolling Stones, but Pink Floyd or the Moody Blues were another matter.

More or less simultaneously, as ‘roadies’ metamorphosed into ‘sound engineers’, they realised that Audiomasters could be chained, much as WEM power amps could, which led to multiple audio channels becoming available. Like Parkinson’s law (‘Work expands to fill the time available’), as the number of channels available increased, so did the number of sources, and soon instrument miking became the order of the day.

“The 4x12 column was still the mainstay — I’d done 4x10s and even the ridiculous 6x8s, but I further developed the 4x12 because I still liked the Goodmans Audiom woofer. I’d have one column with that, one with the 301s and, because it was a bit bottom–ended, I’d put up a narrow column with three Celestion MF 100 horn tweeters to balance it — and that was the classic WEM PA. That was the sound that took off: the thin column sandwiched by the two big ones per side was the classic system — 200 Watts.”

How, Where & WEM

Two things really set WEM apart from the rest of the pack in the late 1960s and ‘70s. The first was that Charlie himself was such an enjoyable and approachable character. He formed a genuine friendship with many of the musicians who used his equipment, including Jimi Hendrix, with whom he shared the occasional bag of chips pre–gig; David Bowie, who wrote much of ‘Space Oddity’ in his office (“I didn’t mind him eating his fish and chips off my desk but I did have to tell him to take his bloody feet off my desk! He’s a smashing bloke!”) and Marc Bolan, who wrote Charlie a book of poems in thanks. Charlie may have been from an entirely different generation but musicians loved him — possibly because he was from another generation, and yet quite unlike the judgemental parental figures they were used to. The second factor was his restless inventiveness. Charlie was never satisfied with what he’d achieved.

The back cover of Pink Floyd’s Ummagumma album. Pink Floyd were avid users of WEM PA gear.“Whatever you do with columns, you can’t project bass from them, so I made an exponential horn — a gigantic one coupled to a box with four Celestions in it, facing each other into a three–inch channel with the horn bolted on. Slade wouldn’t play without them. That was a lovely bass sound. In fact the man who ran the lab at Celestion was interested in what I was doing with this and asked me to take the system down there so they could test it in their anechoic chamber. So off I went to Ipswich and they put it in the chamber and measured it with their Brüel & Kjaer gear, and afterwards they just looked at me and said, ‘How did you do that? It’s dead flat!’”

The back cover of Pink Floyd’s Ummagumma album. Pink Floyd were avid users of WEM PA gear.“Whatever you do with columns, you can’t project bass from them, so I made an exponential horn — a gigantic one coupled to a box with four Celestions in it, facing each other into a three–inch channel with the horn bolted on. Slade wouldn’t play without them. That was a lovely bass sound. In fact the man who ran the lab at Celestion was interested in what I was doing with this and asked me to take the system down there so they could test it in their anechoic chamber. So off I went to Ipswich and they put it in the chamber and measured it with their Brüel & Kjaer gear, and afterwards they just looked at me and said, ‘How did you do that? It’s dead flat!’”

Hum & Awe

As well as Mick Jagger (see the ‘Stones In The Park’ box), another singer who took a serious interest in sound quality was Janis Joplin. “John Thompson, who’d been with us since the early 1960s, went to the Albert Hall, where she was appearing, and put our best system in. She announced from the stage that she had never ever heard her voice relayed to an audience as she had that night. She came off stage, thanked John Thompson and then broke down into tears, she was so pleased with what he had done.”

There is some debate as to which system this actually was. On his own web site, Charlie said that the Janis Joplin rig was the first WEM Festival stack, comprising a pair of 15–inch speakers, six 10–inch speakers for mids and highs and a Vitavox or Celestion horn for the top end. Others say that the Festival stack first appeared at the Isle of Wight festival. In any case, whichever system Janis Joplin sang through at that gig, she loved it.

”Straight away, her management company ordered that exact same sound system to be flown to America. They got it to America and her sound crew, I’m afraid, though they were experienced sound men, didn’t understand what we were doing and so they ended up with a massive earth hum. They did one show and had to resort to the house PA, and whatever I said to them, I was told ‘No, no, we know what we’re doing...’ Only they didn’t, so in the end they said ‘Come over.’ They booked me into the Waldorf Astoria — I felt really important! I got to New York and they told me she was going to Tennessee, so they promptly put me on the plane too. We got to Tennessee, it was ever so hot, and I sat down on the kerb because I was so tired and she came over and sat down beside me saying, ‘Well, what do you think Charlie? What shall we do tomorrow?’

“So we got to the hall and every speaker was humming — it was ridiculous. I said ‘What have you done?’ and the man said, ‘Well, these idiots in England have taken all the earth wires off, but I put them back on again!’ I was... a bit rude to him. I said give me all the screwdrivers you’ve got and all the guys you’ve got. I took all the earths off and she came on for her first number, ‘Try A Little Harder’, which she did with a violin player. He was good and I wanted him up in the mix. They didn’t want me to touch anything, so I just leaned over and did it anyway. Then the police came on because she’d said a bad word on stage and the kids were thrusting onto to the stage as they do. It was another bad night but at least the sound was all right at last!

“I had to get up at four in the morning to catch my flight back to London, and as I sat there eating egg and bacon, there was Janis wandering around the swimming pool, a bit out of her head. She came over and I ended up feeding her bits of egg — she was starving. Nobody was looking after her. A month after that she died.”

The Wight Stuff

And then there was the Isle Of Wight Festival. Or rather, festivals, plural, because there were two that WEM were involved in, though the first has been much obscured by the ill–fated second.

“The first one, the Bob Dylan one, was good.” The line–up was actually Bob Dylan, the Band, the Nice, the Pretty Things, Marsha Hunt, King Crimson, the Who, Third Ear Band, Bonzo Dog Doo–Dah Band and Fat Mattress. “It was a nice atmosphere and the sound, once again, was brilliant. You could have heard a pin drop, and every group that was on you could hear so well. With Dylan and the Band it was like listening to a hi–fi record, but the second one, the Jimi Hendrix one in 1970, started off with bad vibes. The Who were particularly difficult.”

Opinions differ as to what went wrong. Certainly, the organisers, the Foulks brothers, had big plans. Woodstock had taken place the year before and the Isle Of Wight’s line–up was similarly mind–boggling (particularly in retrospect), including the Who, Free, the Doors, Melanie, Jethro Tull, Donovan, Family, Joni Mitchell, the Moody Blues, Sly & The Family Stone and Jimi Hendrix, who was headlining what turned out to be his last ever gig.

It also saw the debut of the parabolic speaker mentioned earlier, which had some remarkable properties, but wasn’t enough to prevent sound problems ruining the gig. “Rikki Farr, who was the MC, thought the trouble was down to some Algerians that turned up, demanding free festivals, but I say once trouble starts it just starts. I was on the stage with Melanie, putting the gear up, when she started performing and some big ugly sod came along and threw a tin of Coke at her. How low can you get? And then there were people walking around with axes... And what brought it on? A rotten sound.

Jimi Hendrix’s last ever performance, at the Isle Of Wight Festival in 1970.Photo: Dimbola Lodge / www.dimbola.co.uk“There was all the Who’s gear and all someone else’s gear, I forget who, about 5000 Watts’ worth, plus all the monitors you could think of, but a silly little wind blew up and it was louder behind the stage than it was out front. That’s what brought all the bad vibes on — a bad sound. Everything that was bad in people came out at that festival. A lot of bad drugs, too. Jimi Hendrix was in a terrible state. He said ‘Charlie, I can’t hear myself,’ and I ended up taking half the system down and pointing it at his ear — 500 Watts! I’d put about 16 columns round him because he kept saying he couldn’t hear what he was doing. You can hear it on the recording, Jimi saying ‘Turn it up, Charlie!’

Jimi Hendrix’s last ever performance, at the Isle Of Wight Festival in 1970.Photo: Dimbola Lodge / www.dimbola.co.uk“There was all the Who’s gear and all someone else’s gear, I forget who, about 5000 Watts’ worth, plus all the monitors you could think of, but a silly little wind blew up and it was louder behind the stage than it was out front. That’s what brought all the bad vibes on — a bad sound. Everything that was bad in people came out at that festival. A lot of bad drugs, too. Jimi Hendrix was in a terrible state. He said ‘Charlie, I can’t hear myself,’ and I ended up taking half the system down and pointing it at his ear — 500 Watts! I’d put about 16 columns round him because he kept saying he couldn’t hear what he was doing. You can hear it on the recording, Jimi saying ‘Turn it up, Charlie!’

“The first trial afternoon, with minimal audiences, about 20,000 people, they started off by crashing the fences down to get in, and then more people turned up with some banners saying festivals should be free. I mean it was only about 10 bob [50 pence] to get in — the best buy anybody could have had! These were intelligent people behaving like bloody madmen. But when one starts it’s like a snowball. There was a band on from America on the trial afternoon, with a song called ‘Tell It To The Stones’, hoping everyone would join in. They joined in, all right, singing, ‘Turn up the volume,’ along with a hail of bricks.

“I realised then that though it sounded all right to us, they couldn’t hear. I turned the volume up, the needles were hard over into the red but there was no sound and I couldn’t understand it. The Who were on later and they were going to do their own mixing, but they couldn’t get anything out of it, either.

“They said I could try something with the sound and I thought maybe some presence would help it cut through. Peter Watts, the Floyd’s roadie, went out with a walkie talkie and he kept telling me he couldn’t hear it but this was at about 4500 Watts, and when I turned the presence up, he said it was good but it was an empty sound, just a squashed–up little sound. Meanwhile, Ray Foulks had gone home and he phoned the stage and said ‘You’ve done it, you’ve cracked it! I’m five miles from you and I can hear every word!’ I said, ‘Ray where do you live in relation to the stage?’ and he said ‘Five miles behind it!’ So all the sound was being blown behind us. You could have put a million Watts in and you wouldn’t have heard anything. There was nothing I could do — it was a bitter pill. Rikki Farr said he’d take a helicopter to London to pick up some horns, and then I got carted off because I fell over with nervous exhaustion and I was laid up in a hut somewhere. The Who came on and there was so much trouble with the sound, people started fighting and I thought ‘OK, that’s about where I come in.’ It was like watching a house of cards tumbling down.”

It wasn’t just any old wind that had blown in; it was a chill one from a dark place. The Stones had staged their tombstone gig for the age of Flower Power not so long before, and Haight Ashbury was already a hazy memory. As for the Isle Of Wight, the disputed turnout (150–200,000, but who was counting?) resulted in a Government act to prevent further festivals on the island without a special permit. It was probably just as well. The mood was turning nasty.

Photo: Dimbola Lodge / www.dimbola.co.ukThere were commercial considerations, too, Charlie recalled. “After a while, it all got too much for the bands. The systems got bigger, which meant another van on the road and another sound man and so gradually people started hiring and the whole thing changed. By about ‘73 I felt I didn’t have anything left that I wanted to do. At Stones In The Park there were a quarter of a million people there and not one policeman was needed — not a single bobby. I was disgruntled and suddenly one day I remembered a guy playing ‘The Bells Of St Mary’s’ on an accordion in the mess room, and I decided that was what I wanted to do. I wanted to go back to the accordion — there was something that could keep me busy for the rest of my life.

Photo: Dimbola Lodge / www.dimbola.co.ukThere were commercial considerations, too, Charlie recalled. “After a while, it all got too much for the bands. The systems got bigger, which meant another van on the road and another sound man and so gradually people started hiring and the whole thing changed. By about ‘73 I felt I didn’t have anything left that I wanted to do. At Stones In The Park there were a quarter of a million people there and not one policeman was needed — not a single bobby. I was disgruntled and suddenly one day I remembered a guy playing ‘The Bells Of St Mary’s’ on an accordion in the mess room, and I decided that was what I wanted to do. I wanted to go back to the accordion — there was something that could keep me busy for the rest of my life.

A telegram from T–Rex to Charlie Watkins.“Also, Kelsey and Morris had come out with a version of the W–bin at about that time, but their system was better than the W–bin and they were better than me. Although they were terribly heavy to carry, I could see what was going to happen. There they were with a 500 Watt box against a great big WEM system, and it seemed like it was time for me to hang up my headphones. So I just stopped.”

A telegram from T–Rex to Charlie Watkins.“Also, Kelsey and Morris had come out with a version of the W–bin at about that time, but their system was better than the W–bin and they were better than me. Although they were terribly heavy to carry, I could see what was going to happen. There they were with a 500 Watt box against a great big WEM system, and it seemed like it was time for me to hang up my headphones. So I just stopped.”

There were other factors, too, which Charlie expanded on when I expressed surprise that he walked away after having achieved so much. “Well, you see, they started calling it pollution, which didn’t go down well with me — especially when it might have been a little bit true. They claimed that at Grangemouth [in 1973] it was a constant 128dB, which was supposed to be dangerous. Then there was a bloke with a knife at a gig and the audiences started to change... It was all starting to worry me. So I went to see a Harley Street specialist and I asked him if it was possible that I could be responsible for making people go deaf and he said, well, if it gets too loud, yes. I can hear as good as anybody today, and that after I’d sat in front of PAs for Thin Lizzy and Slade night after night! Well, someone had to be wrong, but either way it didn’t leave a very good taste in my mouth. And what else was I going to do anyway? There weren’t any holes that needed filling, so I decided to get out. And I went back to designing a wire–stripping machine.”

End Of An Era

Around 1974, Charlie Watkins paid his staff off, sold his factory, moved into a small unit and returned to his beloved accordion. Of course, that wasn’t the end of the story. For the rest of his life he remained an inventor. He developed new accordions, perfected amplifiers that became the standard for the top accordion players and even pioneered MIDI accordion systems. Right to the very end of his life, he and his devoted wife, June, ran their business, latterly from their home in South East London. He never stopped working to achieve a perfect sound.

You can’t easily sum up Charlie Watkins’ achievements. Yes, he more or less invented the modern PA mixer, amp slaving and foldback, and I’m not the first to have looked at the best WEM columns and thought ‘line array’! But it’s as much a human story as a technological one. Charlie Watkins was a remarkable man, genuinely loved and admired by so many who knew him, and a true original.

Asked about the best PA sound he’d ever heard, Charlie said: “Well, my ego in this part of my brain is in conflict with my honesty, which occupies a much smaller part of my brain and honesty, I’m afraid, is winning. The PA they’ve got now, especially that Britannia Row, it’s amazing. It’s still basically the same idea — a mixer, speaker system and monitors — but the sound quality today from those line arrays is amazing.” But for all that, he concluded, the sweetest sound he ever heard came from his beloved Goodmans speakers. That and, no doubt, the accordion, with which he remained fascinated to the end.

Stones In The Park

It’s hard not to come back to the Stones In The Park gig in 1969, if only because it was such an unprecedented spectacle and is still so often screened around the world on late-night TV.

“The Stones In The Park was a story. Andrew Loog Oldham and Pete Jenner, two great guys, had decided to do this gig but they didn’t have a PA for it, and the first thing I heard was a call from Ian Stewart, their roadie, saying, ‘Charlie, we’re down at the Odeon in Nine Elms and we’re trying to have a rehearsal but Mick’s creating because he hasn’t got a PA system.’

“I had a shooting brake at the time and took a system round there and Mick was testing me, seeing what I did on the Audiomaster. That was when I realised that Mick Jagger was a guy who really had it in his head precisely what he wanted. He’d say, ‘Charlie that’s fine but I need a bit of so and so here.’ Short of him turning the knobs himself, he couldn’t have had a clearer idea of what he wanted.

“The gig itself was a wonderful, wonderful day. They had a marvellous MC in Sam Cutler, and the whole atmosphere was good. Even the Hell’s Angels were marvellous, carrying all our columns for us. At the start, one of them came over and started to pick up one of our columns and I said, ‘Oh, don’t let him touch it!’ and someone said, ‘It’s OK, they’re tame today,’ and they were. They put all the gear up for us, spread it all across the stage. It was only a 1500 Watt system and yet you could hear it in Edgware, seven miles away — the loveliest sound I’ve ever heard, everything was right. I had half my factory down there.”

Though the rig used was ‘only’ rated at 1500 Watts, WEM didn’t actually have that much gear to hand, and it says a lot for the spirit of the era that bands would lend gear back to Watkins so that he could undertake these ambitious events. In the case of the Hyde Park gig, this involved borrowing columns from T–Rex — indeed, it was T–Rex’s roadie who helped assemble the system.

It wasn’t Charlie’s only experience with Their Satanic Majesties, either. “It was the Stones, or rather Mick Jagger, who insisted that I started mixing the sound from the front. It wasn’t the very first time I’d done that, but I’d got a bottle on my head, so I wasn’t very keen and I wasn’t going to put my life on the line. But Jagger had this platform made for us. When John Thompson and I drove our big Commer van round the back of the Palais de Sport in Paris, what did we come across but all the local gendarmerie, complete with snarling dogs. We got to the gig and there was a full–scale riot in progress. The crowd were using these little flat plates that scaffolders use — just flicking them across the auditorium like cigarette cards. The more the security beat them up, the worse they became — just like what happens in England. So I thought, I’m not going out there, and I told them I wouldn’t do it. It got so bad that nobody knew what to do. I went up and knocked on Jagger’s door and told him I didn’t want to go out there on this platform in the middle of a riot, but that he could probably calm them down. So he came down, took a microphone and said: ‘Hey! Cool, man, cool,’ And it was like magic. Mind you, I still wouldn’t go out front! After that we went everywhere with them in Europe. It was great.”

All About The People

Somehow, in the middle of all the rock & roll insanity he encountered, Charlie Watkins remained untouched. Born into a completely different world, he didn’t even like rock & roll, but he liked the people who made it and he loved the challenge of making them sound good.

I asked him what was the best sound he’d ever heard from one of his systems, fully expecting him to name Pink Floyd, who became probably the biggest users of WEM equipment and who had proudly included their WEM PA as part of the sonic payload depicted on the rear of the 1969 Ummagumma album. But that wasn’t his answer at all. “No. Mike Patto’s Time Box should have had that reputation, because they used to do magic with it — later they became Patto, a Roundhouse sort of band. Another great sound was the Moody Blues. When they came out, Mike Pinder was on the phone, a very nice guy, saying he wanted a PA. He and his manager took me down to some posh steak house in the West End and tried to do a deal. In the end he said, ‘For Christ’s sake stop staring at that meat and let me tell you that we’re bloody broke but we want your PA!’ Well that’s different, isn’t it? So I lent it to them and said when they had some money they could pay for it. They had this date at the Festival Hall and I was in the audience and the sound was devastating. That was the third best I ever heard. Stones in the Park was the second best.

“The Floyd were great, though, because they had 10 times as much, and Roger [Waters] was a great visionary and a great experimenter. It was he who did the sound-in-the-round thing. We’d go to the Albert Hall and they’d get the First Battalion Grenadier Guards, or whatever, to take cannons up there — you’d never know what you were going to face! Once they wanted to throw potatoes at the big gong Nick Mason used to hit with his mallet, and I had to mic that up — and I did it very well in fact! Roger was always searching... him and Peter Watts.”