Norbert Putnam was part of the original Muscle Shoals rhythm section, and as a million-selling producer, helped to bring pop music to the country capital of the world.

They named a street after the late Chet Atkins off Nashville's Music Row, and a park after the late Owen Bradley, the two producers who are regarded as establishing the Nashville Sound as it's known today. They might well get around to doing the same for Norbert Putnam some day — he's owned and traded about the same amount of real estate around the Row as both Atkins and Bradley, and owned more studios than the two of them put together. And he was the originator of that other Nashville sound, the one that's got little to do with steel guitars and fiddles; the one Nashville ultimately embraced in its rush to pop music in the 1990s.

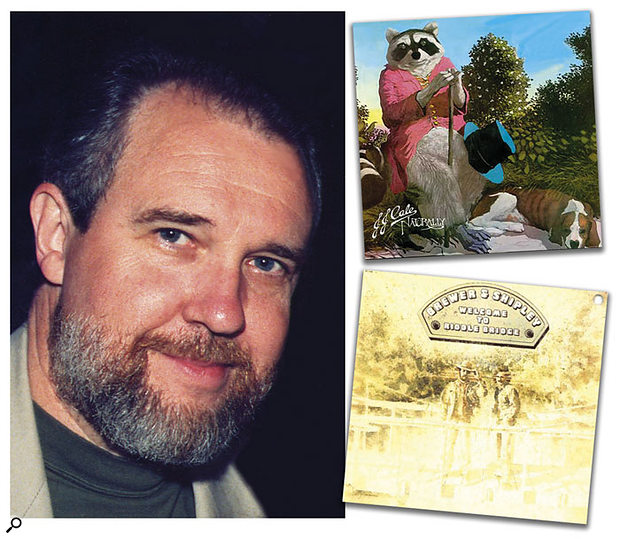

While Nashville was focused on country music through the 1960s, '70s and '80s, Norbert Putnam was producing much if not most of the non-country music that passed through the city during that time. His productions included records that established such artists as Jimmy Buffett, Joan Baez, Dan Fogelberg, Brewer & Shipley, Pousette Dart Band, Donovan, John Hiatt, JJ Cale, the Flying Burrito Brothers and the New Riders Of The Purple Sage. If it wasn't country and it wanted to come to Nashville, it usually wound up on one of Putnam's doorsteps, the ones leading to the four seminal recording studios that he was involved in, including Quadrafonic, the Bennett House, Georgetown Masters and Digital Recorders.

Beyond The Doorstep

Putnam liked to fiddle as much with the technology as with the music, as well. Talking from his current home, in Grenada, Mississippi, where he is currently working on the design for the soon-to-be-constructed Delta State University Recording Centre (the orchestral room there will be modelled on Studio One at Abbey Road, where Putnam did string sessions for productions), Putnam recalls how he helped shepherd in the age of transformerless microphone preamps. "When David Briggs and I started Quadrafonic Studios in in Nashville, in 1970, we had a Quad 8 Class-A fully discrete console with Jensen transformers and high-low shelving EQs," he remembers. "About five years later, console automation started to get big and we knew we had to upgrade, so we got one of the MCI 500-series desks that Jeep Harned was designing and building. We wanted a Trident A-Range, because we loved that British sound, but back then they cost around $175,000 which was a lot of money; the MCI only cost about $25,000. It gave us automation, but we weren't very happy with the sound of the mic pres, especially after having worked with the discrete ones on the Quad. But one day this guy, Paul Buff, who had a company called Allison Research in Nashville [which would later become Valley People], came to the studio to talk about this VCA automation system he had developed and I mentioned my feelings about the mic pres. He said he remembered there was this old Bel Labs design for a transformerless mic pre which he thought he could modify for this console. He said he could do it in about a week. A week later he comes in with this box with a couple of patch cords hanging off it, and we plug it in and A/B it with the MCI mic pres, and sure enough, this transformerless one sounds better. It sounds just great — fast transient response, high slew rate and no transformer. So I mentioned it to Jeep Harned and he says if they really do sound better than his mic pres, he'll pay for the installation of the Allison ones in my console. And when he heard them, sure enough, he agreed and paid for the switch. Within a few years, everyone had pretty much switched to transformerless."

More Muscle

But before there was technology, there was just plain music. Norbert Putnam was part of the Muscle Shoals crew brought to Nashville by Elvis Presley producer Felton Jarvis in 1965, because RCA Records artist Presley used his label's studios there and Jarvis wanted musicians with more of an edge than the current Nashville A-Team which included drummer Buddy Harmon, bassist Bob Moore and guitarist Grady Martin. Over the course of a few years between 1964 and 1967, much of the core of the original Muscle Shoals team headed north to Nashville, including Putnam, keyboard player David Briggs, drummer Jerry Carrigan and saxophonist Billy Sherrill, a crew that would become Nashville's second generation of first-call session players. Putnam, a bassist, became a musician simply because, he says, "There was nothing else to do in Muscle Shoals back then. If you didn't play music there was nothing to do. It was such a small town that if you stole a car they'd know who stole it."

Muscle Shoals is a small town with a big history, tucked in the hill-and-lake country in the northwest corner of Alabama and about a three-hour ride from Nashville. The place was a momentary blip on the peripatetic journey of R&B music on its way to Detroit and elsewhere, leaving behind a small but talented collection of white southern musicians and writers on whom R&B's voodoo had a lasting effect. The first hit black artist the town produced was the late Arthur Alexander — who at the time was the bellhop at the Muscle Shoals Hotel — with his recording of 'You Better Move On'. The manager of the local movie theatre, Tom Stafford, then a gangly kid, would offer the musicians free passes to the movies in exchange for playing on his demos, recorded in the dilapidated offices above his father's corner drugstore, playing to an old Roberts mono tape recorder with only enough microphones to record half the drum kit and a Heathkit recording console with no volume fader — the fade-outs were accomplished by turning the console off and letting the tubes die out.

Muscle Shoals is a small town with a big history, tucked in the hill-and-lake country in the northwest corner of Alabama and about a three-hour ride from Nashville. The place was a momentary blip on the peripatetic journey of R&B music on its way to Detroit and elsewhere, leaving behind a small but talented collection of white southern musicians and writers on whom R&B's voodoo had a lasting effect. The first hit black artist the town produced was the late Arthur Alexander — who at the time was the bellhop at the Muscle Shoals Hotel — with his recording of 'You Better Move On'. The manager of the local movie theatre, Tom Stafford, then a gangly kid, would offer the musicians free passes to the movies in exchange for playing on his demos, recorded in the dilapidated offices above his father's corner drugstore, playing to an old Roberts mono tape recorder with only enough microphones to record half the drum kit and a Heathkit recording console with no volume fader — the fade-outs were accomplished by turning the console off and letting the tubes die out.

"We'd hang out with Tom, go to the movies then go upstairs over the drugstore," recalls Putnam. "Occasionally he'd go down and fill a codeine cough syrup prescription and share it with us. Arthur Alexander was coming over and bringing songs to Tom. Tom got Arthur together with Rick Hall [founder of the legendary FAME Studios who would go on to produce Alexander and other country, pop and R&B artists], who was the bass player in a band called the Fairlanes. Billy Sherrill [who went on to produce Tammy Wynette and run Columbia Records in Nashville] was the sax player in that band. Rick called up Briggs, Carrigan and me. We did two songs, one of which was 'You Better Move On', and got in his car and drove to Nashville and played the tapes for Chet [Atkins] and Owen [Bradley] who said they couldn't do anything with it because it wasn't country. So Rick found Noel Ball, the leading DJ in Nashville. He had a sock hop on a local television channel on Saturday. He was the Dick Clark of Nashville. He also worked for a record company."

Norbert Putnam at Quadrafonic, with an unconscious Joan Baez.The record made the top 10 two months later.

Norbert Putnam at Quadrafonic, with an unconscious Joan Baez.The record made the top 10 two months later.

"That launched Muscle Shoals as a recording centre," says Putnam, who goes on to describe what made this tiny dot on a map so musically unique. "It wasn't as soulful as Memphis. We were listening to Burt Bacharach and Bobby Blue Bland. We had experience playing black music, but it didn't come out as black as Memphis. The profits from that record funded Rick Hall's FAME Studios. It also attracted [publisher/producer] Bill Lowery out of Atlanta with his R&B acts. He brought Joe South, Billy Joe Royal, Ray Stevens, Jerry Reed and Tommy Roe and his bubblegum hits. It was black music but with a white rhythm section. Felton Jarvis would come down to do Tommy Roe for Bill Lowery. Once we got there, we ended up playing for [Monument Records founder and producer] Fred Foster on sessions for Presley and Roy Orbison."

Putnam credits Hall with moulding him into what would become a top-notch musician, and then producer. "When I was young and working in Muscle Shoals, I didn't know about inventing bass parts, so I was copying other people's parts," Putnam recalls. "If a song sounded like a Drifters song, me and the drummer would play a Drifters part. Then one day Rick came out and said to me, 'We already have Drifters records — you need to come up with something new.' And I've tried to apply that to every session I've ever worked."

Enterprising Music

Through the 1960s, the Muscle Shoals musician club grew, based mainly out of producer Rick Hall's FAME Studios (the name Fame was an acronym for 'Florence, Alabama Music Enterprises', after a neighbouring town where Hall had his first studio in a converted tobacco warehouse), and together they played on over 500 hit records of all genres.

The Muscle Shoals players who moved to Nashville were soon playing demos for producers Wesley Rose and Jerry Bradley at RCA. "From those demos came all the master sessions. The producers hired us based on those demos," says Putnam. "By 1970 I was doing about six hundred record dates a year." Those sessions included Bobby Goldsboro's 'Honey', Tony Joe White's 'Polk Salad Annie', JJ Cale's 'Crazy Mama' and several Presley hits, as well as the Monument artists Roy Orbison and Boots Randolph.

The Nashville Putnam came to in 1965 had few studios; he recalls only RCA's two rooms, Studios A and B (the latter now a museum run by the Country Music Foundation), and the Quonset Hut, built by Owen Bradley and later sold to CBS Records, after which Bradley built his famous Barn studio, where he recorded classic records with Loretta Lynn and others. Fred Foster had Monument Studios, part of his record label, where he produced records for Roy Orbison.

Like his cohorts in Nashville's factory-like studio trenches, Putnam was approaching burn-out from all those sessions. But when Bob Dylan came to the city to record his influential Nashville Skyline album in 1969, it put Music City onto the larger map of the new mainstream pop music. Dylan changed folk music forever when he went electric at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, and then helped lay the foundation for the coming fusion of country and rock; following his lead, bands like the Byrds were suddenly looking to Nashville as a new resource for music away from the already jaded environs of LA.

Purple Patches

The best producers have the ability to make a successful album from the most unpromising beginnings, and that's exactly what happened when Clive Davis asked Norbert Putnam to produce the New Riders Of The Purple Sage. They were putatively a band, but in reality more of a concatenation of hippies with access to electrified instruments who lived north of San Francisco in a communal house. "Clive says to me, 'I'll be honest with you — you're my fourth choice. Three other producers have already turned me down. But these guys are opening for the Grateful Dead and they're playing in front of 10,000 people a night.' Clive called them 'the Nearly Dead', and I knew I was going to have to smoke a joint just to think about working with them. Oh, and they're also pretty questionable musicians, and I'm used to the best in Nashville. But then he also told me that because of the exposure the band was getting with the Dead, he could guarantee the album would sell 500,000 units."

For independent producers who were now getting larger and larger shares of the points based on sales from records in addition to fees, the lure was too great for Putnam to resist. So in 1973 Putnam made the trek to Northern California to meet the band. Upon arrival, he was picked up by a hippie right out of Central Casting, complete with VW Microbus, who proceeded to drive Putnam to the band's communal abode. "We get there and the house is up on a hill in the middle of what looked like a wheatfield," he remembers. "The women are all walking around wearing mumus and the kids are running around naked, and here I am this clean-cut guy from Nashville walking into all of this. I was ready to call it a mistake and walk away then and there."

For independent producers who were now getting larger and larger shares of the points based on sales from records in addition to fees, the lure was too great for Putnam to resist. So in 1973 Putnam made the trek to Northern California to meet the band. Upon arrival, he was picked up by a hippie right out of Central Casting, complete with VW Microbus, who proceeded to drive Putnam to the band's communal abode. "We get there and the house is up on a hill in the middle of what looked like a wheatfield," he remembers. "The women are all walking around wearing mumus and the kids are running around naked, and here I am this clean-cut guy from Nashville walking into all of this. I was ready to call it a mistake and walk away then and there."

Before Putnam could do that, however, the Riders' lead singer and vibemaster Marmaduke walked out and greeted him. "Marmaduke says we have to have a band meeting and we all walk out into the middle of the field. We sit down on the ground and the wheat is so high I can only see people's heads. I had this speech rehearsed and was ready to tell them this wasn't going to work. I put my hand up to make a gesture and all of a sudden this butterfly lands on it. The band sees this. They stare at it. No one says a word. Then Marmaduke pipes up and says 'That's an omen, man! You're our producer. You've been chosen!' I think to myself, you gotta play the cards you're dealt. So I say fine, let's do it."

The Adventures Of Panama Red wound up being the only platinum record the Riders ever had. Putnam had to sneak a few musicians onto the project to buttress the Riders' playing skills, and still the project took four weeks at the Record Plant in Sausalito just to get 10 usable basic tracks. "If Spencer Dryden didn't drop his sticks during a song, then we had a take," Putnam recalls ruefully.

Becoming A Producer

And it was a veteran folkie and a brilliant, eccentric and dissolute songwriter who changed Putnam's career course from musician to producer. Putnam had played on several Joan Baez albums in Nashville, produced by her long-time recording mentor Maynard Solomon, who also owned her record label, Vanguard Records. But in 1970, Baez had become enamoured of composer Kris Kristofferson, who had stood Nashville's staid songwriting community on its ear a few years earlier with songs like 'Me And Bobby McGee', which Janis Joplin had turned into a radio anthem, and the brooding 'Sunday Morning Coming Down'. She chose Kristofferson to produce the record.

Putnam's partnership with Jimmy Buffett yielded lasting success and a classic hit single, 'Wasted Away In Margaritaville'.Meanwhile, Putnam and David Briggs had moved forward with an idea for a recording studio in Nashville that would let them indulge their fascination with technology, do their demos as would-be producers and perhaps make a few quid in the process. Producer Elliot Mazer, who worked on Linda Ronstadt's Silk Purse recording in Nashville, upped the ante by telling Putnam and Briggs he would bring projects to a leading-edge facility there.

Putnam's partnership with Jimmy Buffett yielded lasting success and a classic hit single, 'Wasted Away In Margaritaville'.Meanwhile, Putnam and David Briggs had moved forward with an idea for a recording studio in Nashville that would let them indulge their fascination with technology, do their demos as would-be producers and perhaps make a few quid in the process. Producer Elliot Mazer, who worked on Linda Ronstadt's Silk Purse recording in Nashville, upped the ante by telling Putnam and Briggs he would bring projects to a leading-edge facility there.

They fitted the studio — which is still located on Grand Street off Music Row, but now owned by the coincidentally similarly named Quad Studios of New York City — with the Quad 8 desk and a 16-track Ampex MM1100 two-inch deck. Putnam had been talking with CBS Laboratories engineers in Connecticut about their work with the nascent quadraphonic format, and sensing a trend, he chose Quadrafonic as the studio's name. "We stuck a pair of JBL 4310 speakers in the back of the room and bang, we had quad," laughs Putnam. The studio had quickly become a hangout for those disenfranchised by the Nashville oligarchy and for the swelling influx of young musicians and writers who were coming to Nashville in Dylan's wake. So it wasn't surprising when Kristofferson, who was known to have a cocktail or two at the time, agreed to use Quad to make what would be Baez's Blessed Are album. It also wasn't surprising, at least in retrospect to Putnam, that Kristofferson, who was painfully shy in the studio, intimidated by the technology and the musicianship, and who needed a belt to work up the nerve to bring his gravelly voice in front of a microphone even for demos, came to the first session tipsy and pleaded with Putnam, the bassist and arranger, to take over production chores, as well. The sessions went quickly, including the recording of a cover of The Band's 'The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down', which was Baez's first hit single.

Home Free

This event did not escape the notice of Clive Davis, then president of Columbia Records in New York. He flew Putnam to Manhattan and fêted him for making a record with a folkie and selling 1.5 million copies. "He called me a genius," says Putnam, still bemused by the meeting nearly 30 years later. "I had never been called that before. So I said, 'Mr. Davis, it's my only record as a producer. I might have gotten lucky.' He said 'You must know something, because she's made 10 records and none of them ever sold more than 100,000.' Then he looks at me and says, like this was going to be the greatest honour a man could bestow upon me, 'I want you to produce all the folkie artists on CBS Records.' I thought to myself, I have died and gone to hell! This would be like conducting an orchestra made up of banjos. I had grown up in Alabama and I liked soul music. Clive said he had just signed Gamble & Huff out of Philadelphia to take care of that for him. Then Clive grabs a tape box and slides it across his desk to me. It was a demo of a guy named Dan Fogelberg."

Perhaps the highlight of Putnam's distinguished career as a session bassist was his work with Elvis Presley.Putnam produced Fogelberg's debut record, Home Free, released in 1973. The record, however, didn't live up to Davis' expectations and it wasn't promoted well. But there was hope. "It was beginning to look like his career was over before it had started, but Dan called me from the road one day that year," says Putnam. "He was playing in Jackson, Mississippi, and he was screaming into the phone telling me that 2,000 people had turned out to see him. Seems a local radio station had played the record and it was getting great response. So a while later, his manager Irving Azoff went to see Clive and asked Columbia to release him. Clive agreed. Then Irving takes the elevator down two floors, walks into [Epic Records president] Don Ellis's office and gets him signed to Epic Records. All in less than an hour or so."

Perhaps the highlight of Putnam's distinguished career as a session bassist was his work with Elvis Presley.Putnam produced Fogelberg's debut record, Home Free, released in 1973. The record, however, didn't live up to Davis' expectations and it wasn't promoted well. But there was hope. "It was beginning to look like his career was over before it had started, but Dan called me from the road one day that year," says Putnam. "He was playing in Jackson, Mississippi, and he was screaming into the phone telling me that 2,000 people had turned out to see him. Seems a local radio station had played the record and it was getting great response. So a while later, his manager Irving Azoff went to see Clive and asked Columbia to release him. Clive agreed. Then Irving takes the elevator down two floors, walks into [Epic Records president] Don Ellis's office and gets him signed to Epic Records. All in less than an hour or so."

Finger Buffett

Putnam's Nashville location during the 1970s put him in the centre of an increasingly peripatetic music industry. Pop acts were coming to Nashville, using the popularity of country music as a springboard into larger audiences. During the mid-'70s, Putnam produced records for Brewer & Shipley, the Flying Burrito Brothers, Steve Goodman (including his breakout single 'City Of New Orleans'), and Eric Anderson, almost all of them at Quad Studios. In between productions, he continued to play a heavy schedule of sessions as a bassist and arranger, on dates for artists including Linda Ronstadt, Kenny Loggins, Bonnie Koloc, The Pointer Sisters and JJ Cale. Putnam would also become the musical midwife to what has grown into a $50 million industry of records, concerts, books, videos, merchandising and gift shops all centered around one seemingly stoned but very ambitious individual.

Putnam's Fender Precision must be one of the most-travelled instruments in rock, but it's on familiar territory here at the Muscle Shoals Hall Of Fame. "I had known Jimmy Buffett for a few years when he was in Nashville," says Putnam. "He used to hang around Quad a lot. Me and David had a sort of open bar policy — anyone could come into the studio and drink for free as long as they didn't bother the clients, and on any given night you'd have people like Guy Clark and Mickey Newbury and Jerry Jeff Walker hanging out there drinking. Jimmy was writing songs and also doing interviews with artists for some magazine he wrote for. He was one of the guys in the hall when I needed a bunch of vocalists to make the chorus real big on 'The Night The Drove Old Dixie Down' for Baez. So he was one of about 20 drunks I dragged in there to make the chorus sound real big. He was signed to Barnaby Records at the time, which was owned by Andy Williams. Some time later, I was in Julian's [a legendary but long-gone four-star restaurant in Nashville] and Jimmy came in and said 'I gotta talk to you.' He ordered me a bottle of Kristal, which was my favourite champagne, so I figured we had at least that in common. He said he wanted to do something more progressive and he wanted me to do it with him. And he wanted to use his band, the Coral Reefers. I thought, this is tragic — I had just been through this with the New Riders [see box]. A bunch of coked-out musicians behind Jimmy singing songs about his grandfather and the ocean. But after a few more drinks the idea didn't sound so bad any more. I went to see them at the Exit/In club, and I told Jimmy, 'Look, if you want to make records about the ocean, you have to get next to the ocean.' I had done that with Fogelberg — he wrote about the mountains, so I recorded him in the mountains [Caribou Ranch Studios, where the 1977 Nether Lands and 1979 Phoenix albums were recorded]. So we booked time in Criteria Studios in Miami. But after the New Riders, I brought ringers in from the start, like Kenny Buttrey on drums and Teddy Irwin in from New York on guitar.

Putnam's Fender Precision must be one of the most-travelled instruments in rock, but it's on familiar territory here at the Muscle Shoals Hall Of Fame. "I had known Jimmy Buffett for a few years when he was in Nashville," says Putnam. "He used to hang around Quad a lot. Me and David had a sort of open bar policy — anyone could come into the studio and drink for free as long as they didn't bother the clients, and on any given night you'd have people like Guy Clark and Mickey Newbury and Jerry Jeff Walker hanging out there drinking. Jimmy was writing songs and also doing interviews with artists for some magazine he wrote for. He was one of the guys in the hall when I needed a bunch of vocalists to make the chorus real big on 'The Night The Drove Old Dixie Down' for Baez. So he was one of about 20 drunks I dragged in there to make the chorus sound real big. He was signed to Barnaby Records at the time, which was owned by Andy Williams. Some time later, I was in Julian's [a legendary but long-gone four-star restaurant in Nashville] and Jimmy came in and said 'I gotta talk to you.' He ordered me a bottle of Kristal, which was my favourite champagne, so I figured we had at least that in common. He said he wanted to do something more progressive and he wanted me to do it with him. And he wanted to use his band, the Coral Reefers. I thought, this is tragic — I had just been through this with the New Riders [see box]. A bunch of coked-out musicians behind Jimmy singing songs about his grandfather and the ocean. But after a few more drinks the idea didn't sound so bad any more. I went to see them at the Exit/In club, and I told Jimmy, 'Look, if you want to make records about the ocean, you have to get next to the ocean.' I had done that with Fogelberg — he wrote about the mountains, so I recorded him in the mountains [Caribou Ranch Studios, where the 1977 Nether Lands and 1979 Phoenix albums were recorded]. So we booked time in Criteria Studios in Miami. But after the New Riders, I brought ringers in from the start, like Kenny Buttrey on drums and Teddy Irwin in from New York on guitar.

Norbert Putnam's current home in Mississippi."One day in the studio, he comes in and starts telling me about a day he had in Key West. He was coming home from a bar and he lost one of his flip-flops and he stepped on a beer can top and he couldn't find the salt for his Margarita. He says he's writing lyrics to it and I say 'That's a terrible idea for a song.' He comes back in a few days later with 'Wasted Away Again In Margaritaville' and plays it and right then everyone knows it's a hit song. Hell, it wasn't a song — it was a movie."

Norbert Putnam's current home in Mississippi."One day in the studio, he comes in and starts telling me about a day he had in Key West. He was coming home from a bar and he lost one of his flip-flops and he stepped on a beer can top and he couldn't find the salt for his Margarita. He says he's writing lyrics to it and I say 'That's a terrible idea for a song.' He comes back in a few days later with 'Wasted Away Again In Margaritaville' and plays it and right then everyone knows it's a hit song. Hell, it wasn't a song — it was a movie."

It was also Buffett's commercial breakthrough record, from 1977's Changes In Latitudes, Changes In Attitudes LP. Putnam kept him near the water when he went back into the studio to produce Buffett's follow-up record, Volcano, at AIR Studios in Monserrat in 1979; Putnam also produced Coconut Telegraph, Somewhere Over China, Songs You Know By Heart — in all about half a dozen Buffett records.

Studio Economics

Putnam's growing number and breadth of productions was taking him further afield. In the meantime, the studio business was changing. Putnam and Briggs sold Quad in 1980 for $1 million to a group of doctors from Atlanta. "We paid $30,000 for the lot and the building in 1970 and put about $125,000 into it in terms of equipment," he estimates. "The second year we were open the business grossed $440,000 in sales. We were getting $150 an hour in the daytime and $165 at nights and on weekends. The economics of studio ownership were great then. But after I sold it, I swore I'd never do it again."

That promise to himself lasted all of six months. That same year, he purchased an 1875 mansion called the Bennett House in the Nashville suburb of Franklin, intending to turn it into a combination residence and private studio. But soon he got calls from Kristofferson and Fogelberg, both of whom wanted to work with him again. That led to others who wanted to use the studio itself, including Mickey Newbury. Putnam had hired the sous chef from Julian's to prepare meals at the studio. When then-Christian music artist Amy Grant went to work there in the early 1980s, she was so taken by both the studio — fitted with a Trident A-Range console — and the chef that she told her manager that she wouldn't work anywhere else. "The chef made that studio," laughs Putnam.

That promise to himself lasted all of six months. That same year, he purchased an 1875 mansion called the Bennett House in the Nashville suburb of Franklin, intending to turn it into a combination residence and private studio. But soon he got calls from Kristofferson and Fogelberg, both of whom wanted to work with him again. That led to others who wanted to use the studio itself, including Mickey Newbury. Putnam had hired the sous chef from Julian's to prepare meals at the studio. When then-Christian music artist Amy Grant went to work there in the early 1980s, she was so taken by both the studio — fitted with a Trident A-Range console — and the chef that she told her manager that she wouldn't work anywhere else. "The chef made that studio," laughs Putnam.

Bennett House was sold eventually, and in 1985 Putnam moved on to Georgetown Masters, a mastering facility he started with mastering engineer Denny Purcell, who passed away last year, and former CBS Records executive Ron Bledsoe. "We wondered, how can we do something different here?" Putnam recalls. The answer was to create a mastering studio that combined the senses of high-end critical listening and home hi-fi, with different speakers and interior designs at each end of the room. "This made mastering more accessible to clients, who felt more like they were in their homes and less like they were in the chemistry lab," says Putnam.

Putnam sold out his interest in Georgetown to Purcell in 1985, and promptly started Digital Recorders, which moved between two locations on Music Row. While Putnam had brought Nashville its first 32-track digital machine, a 3M, at the Bennett House — a format that would become the city's standard for a decade — he expanded on the digital theme at Digital Recorders, installing Nashville's first Sony 3348, among other digital items. "It was always a matter of giving the market something new, and this time it was high-end digital gear," he explains.

The gear had a purpose — to support his self-appointed mission to make the tracks sound good. "All those years working for Nashville producers in Nashville studios, I said to myself that they didn't spend enough time on the tracks," he remembers. "I said to myself that when I became a producer, I would make sure that the tracks held together."

FAME Studios, Muscle Shoals, as it was in the 1960s.But Putnam learned something in his years as a producer; or more precisely, he began to realise something he had actually known all along. "I had been all over the world looking for gear and listening to engineers talk about equipment," he says. "I had worked with Geoff Emerick at AIR Studios in London, and I had him engineer Buffett's Volcano album. I always thought there was some big secret about equipment that I would learn and that that would let me make the best records. Then one day I was working with Bill Schnee. He was at the Bennett House and he pulled out a tape and played it through the monitors and stopped about halfway through and says 'There's the curve — down about 2-3dB at 125Hz, the system rolls off at 40[Hz] and it's a little bright around 10k.' I say, 'How do you know that's the right curve?' And he says 'There is no right. It's whatever works.' You can concern yourself with the equipment all you want, but that's not what makes a great record. Elvis and Felton never worried about a mic-pre. We recorded Elvis with an RE15 — a dynamic microphone, not a condenser. And it had foam padding all around it so that he could move around and not have it pick up noise. We used a U87 on Jimmy Buffett on all the songs and every studio had one, and every studio had an LA2A. It wasn't in the gear. And that's what it's all really about in terms of being a producer: you make the environment right so that the artist can give you an emotionally genuine performance. That's really all there is to it. Felton Jarvis and Fred Foster and the rest of those guys got it right all along: if you could get a great performance out of Elvis or Roy Orbison, then the bass and drums could be a little loose in the track, couldn't they?"

FAME Studios, Muscle Shoals, as it was in the 1960s.But Putnam learned something in his years as a producer; or more precisely, he began to realise something he had actually known all along. "I had been all over the world looking for gear and listening to engineers talk about equipment," he says. "I had worked with Geoff Emerick at AIR Studios in London, and I had him engineer Buffett's Volcano album. I always thought there was some big secret about equipment that I would learn and that that would let me make the best records. Then one day I was working with Bill Schnee. He was at the Bennett House and he pulled out a tape and played it through the monitors and stopped about halfway through and says 'There's the curve — down about 2-3dB at 125Hz, the system rolls off at 40[Hz] and it's a little bright around 10k.' I say, 'How do you know that's the right curve?' And he says 'There is no right. It's whatever works.' You can concern yourself with the equipment all you want, but that's not what makes a great record. Elvis and Felton never worried about a mic-pre. We recorded Elvis with an RE15 — a dynamic microphone, not a condenser. And it had foam padding all around it so that he could move around and not have it pick up noise. We used a U87 on Jimmy Buffett on all the songs and every studio had one, and every studio had an LA2A. It wasn't in the gear. And that's what it's all really about in terms of being a producer: you make the environment right so that the artist can give you an emotionally genuine performance. That's really all there is to it. Felton Jarvis and Fred Foster and the rest of those guys got it right all along: if you could get a great performance out of Elvis or Roy Orbison, then the bass and drums could be a little loose in the track, couldn't they?"

And to punch home that point, so central to his way of thinking, Putnam has one more anecdote that underscored the balance between equipment and talent. "I was on a session with Chet Atkins and some guy comes up to him and says, 'That's the best-sounding guitar I've ever heard.' Chet puts the guitar down on a stand and says back to him 'How's it sound now?' It's all in how you use it."