With a track record that includes hit albums for the Smiths and current chart success with both Blur and the Cranberries, producer Stephen Street is making himself quite a name for his honest and straightforward production approach.

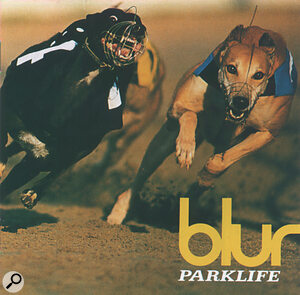

Stephen Street is not a name that immediately springs to mind when one thinks of producers known for their ability to create chart‑topping hits. Yet in the last year alone, his production skills have resulted in two hugely successful albums — one for the Irish band The Cranberries, whose debut album Everybody Else Is Doing It So Why Can't We? has sold nearly two million copies, and one for Blur, whose new album Parklife has had more superlatives heaped upon it than any other album this side of Christmas.

How odd, then, that Street — who has also engineered and co‑produced three best‑selling albums for The Smiths — is still regarded by record companies as a producer of indie‑based guitar bands rather than a man whose abilities have helped create such mainstream hits as Parklife and The Smiths' Meat is Murder, The Queen Is Dead and Strangeways, Here We Come

But that's the way life goes — and in any case Street seems unconcerned about the indie‑based guitar band tag because that's the sort of music he likes producing. "I don't set out to please A&R departments," he says. "I try to make records for the band to like and for me to like." Undoubtedly he achieves what he sets out to do — The Smiths have called him back three times, Morrissey used his skills on his solo album Viva Hate, Blur have used him on all three of their albums and he has just finished recording the second Cranberries album. In a business where fashion so often dictates choice of producer, a producer who can build up that kind of rapport with an act is indeed a rarity.

Beginnings

So how did this extremely young looking 34‑year‑old become a producer in the first place — hard work or an accident of fate? Well, a bit of both really, he says.

"Like a lot of people in this business I started out playing bass and guitar in bands at school," he explains. "And even after I left school and began training to be a surveyor (for my sins), I played in bands in the evening. But eventually I had to make a decision. I loved playing music enough to give up the day job and I worked in pubs to support myself while I tried to find a decent band to join.

"I was playing bass by this stage and eventually I met up with a guy called Bobby Henry who had a band that was signed to the Oval label and was also involved with another band that had a deal with Warners. I played with both bands and through them I got my first chance to be part of something professional. I also got my first taste of recording in proper recording studios — and I loved it.

"Bobby never really found fame and fortune as a musician — although he did go on to discover Hue & Cry — and after a while I realised that as a band we were not getting very far. I felt that I wasn't a good enough musician to become a session player, but I knew I wanted to be in a recording environment."

With the enthusiasm of youth, Street wrote off to virtually every studio in the country asking for a job. He got very few replies, but just as he was about to give up he heard that Island Records had a small studio in Hammersmith and that they were looking for an assistant engineer. "I went along and basically talked them into giving me the job — I was just so enthusiastic that they couldn't turn me down!"

The studio had just been refurbished and Street remembers that his first job was varnishing the wood in the control room, but he soon progressed to more demanding tasks: "I was the only assistant so it was pretty hectic. A recording studio tied to a record label is used every day and there was a lot going on — recording, mixing, editing and so on. Within two years I was promoted to house engineer and was getting some mixing experience. During that time I was so busy learning how to operate the equipment that I hardly played any music at all."

The experience Street gained at Island was invaluable, but in the music business success is just as much about lucky breaks as it is about talent — and for Street that big break eventually came in March, 1984, when The Smiths booked in to record a single with John Porter. The band had just had a huge hit with 'This Charming Man' and they were working on the next big single, 'Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now'.

"I was very young and keen and dying to impress. I was also very excited about this band coming in because I loved their music. We hit it off and they took my phone number, but then the single was mixed elsewhere and the next single was done elsewhere and I thought Oh, they've forgotten about me. That's it — it's gone.

"But a couple of months later I got a phone call from Jeff Travers at Rough Trade saying the band wanted to do the next album without John Porter and would I like to go along and engineer for them. That was the Meat Is Murder Album and it was the project that really got me out of Island and into the outside world.

"It was very exciting working with a band that was creating such a stir. We were all learning — Johnny Marr was getting into arrangement and it was a nice process for all of us. After that album my career really took off. I started to get lots of work from independent labels and to an extent that is the path I have stuck to because my background lies in that kind of alternative indie sound. It's what I enjoy doing most — getting a band, helping to develop it and feeling like I'm part of it if it takes off.

"I've never felt comfortable working with big, established artists. In fact the very first one I did work with was Chrissie Hynde, who asked me to produce four tracks on her new album which we recorded at the end of last year. But apart from that I think I'm really best known for developing new signings. Anyway, I don't think I'm on the top of the A&R list for hit producers — I don't think they see that as my thing. I could charge huge sums of money and be a hit producer for two years but I'd rather do work that I really like and be honest and truthful with my work. If every now and then one of those bands comes through big time then I'm as delighted as they are — I take great enjoyment out of that."

The fact that Stephen Street keeps being asked back by the bands he produces proves the extent to which they feel he is an integral part of the band. But how does he do it? The secret, he says, is as much down to social skills as it is to production techniques. "I always try and get on well socially with the band. If I don't I find the gig won't work. And without blowing my own trumpet, I do seem to get a lot of return gigs."

Street doesn't feel that it has anything to do with creating a 'signature' sound and in fact that is something he actively avoids. He says: "If you listen to The Cranberries and Blur's latest album they sound completely different. What I try and do is take an aural snapshot of the band as they are at that point in their career so that I can capture the essence of the band on tape. I like to be invisible. I don't want to have a trademark sound so that every act I work with ends up getting the same treatment. Having a signature sound does work for some producers — Trevor Horn, for example — and that's fine because people know that although these types of producers are expensive, if they hire them their records will have a certain quality and a certain sound. But I prefer to work differently. I like to bring the best out of the artist and make sure they are truthfully putting down what they want to represent.

"The best bands I've worked with are all very strong‑willed people. They have all got a true belief in what they are doing. In that type of situation you find that the best ideas come from the artist. It's no good when the artist has to lean on the producer to come up with the ideas — that's when you get a factory sound of production because the producer will do the usual little tricks he likes doing all the time. I like it when an artist says 'I want to do this' and pushes me a bit because that makes me work harder and we end up with a better record."

The thrill of working with raw talent can sometimes have its down side though. Some young acts are intimidated by the studio environment which can seem very strange and glamorous at first. The Cranberries are a case in point. Street explains: "They had done some recording in a small studio in Ireland with their ex‑manager, but that had proven to be an horrendous exercise because he was trying to put too much production control over them and in the end he succeeded in breaking everything up to the point where they weren't playing together as a band anymore. Musically, the first thing I had to do was get them back together as a band.

The fact that Stephen Street keeps being asked back by the bands he produces proves the extent to which they feel he is an integral part of the band. But how does he do it? The secret, he says, is as much down to social skills as it is to production techniques.

Great Demos

"One of my favourite tracks on the Cranberries album is 'Pretty' [see boxout], which was basically put down live. I asked them to play me some songs and they played together as a band while Delores (O'Riordan) was standing next to me in the control room doing a guide vocal. They played the track and I said 'that's it — that's the take. There's nothing wrong with that track'. They were so surprised because they had spent weeks working on it on other sessions, breaking down the drums to do this and that and getting nowhere with it. But I felt there was nothing more I could do. The strength of production is to know when something is OK. If it's not broken, don't fix it — there is so much truth in that saying. Some things you do need to tear apart but the talent is to know when to stop and leave something alone.

"I had a similar experience with Morrissey when we were recording the single 'Last of the Famous International Playboys'. I swear that backing track went down on the second run‑through — the guys on drums and bass were still learning it. We did the guitars again, but the actual feel of the track was just wonderful. I came in the following morning and listened and thought 'that's great, that's got a vibe to it', and we used it."

Capturing the elusive sound of a great demo is a problem that all producers have had to face. Street feels guide guitars are just as bad: "When you're doing drums and you put a guide guitar down, you often find that it's a bit out of time, so you come back later to do it again and can you get the same guitar sound again? Can you hell! Same guitar, same amp, same mic, same person playing it, but it's completely different — it drives me up the bloody wall."

Back on the subject of the 'too good to better' demo, Street cites Blur as a case in point. "They make incredible sounding demos," he says. "They have a very good idea of what they are about, and it is hard sometimes when you listen to the demo and think 'what the hell am I going to do with this?'"

The only track on the new Parklife album that Street didn't produce was 'To The End', which is destined to be the second single. EMI, in their wisdom, decided to let Stephen Hague loose on the track — a decision that a lesser man than Street might have found offensive, to say the least. But Street is pragmatic. He says: "EMI thought it was likely to be a huge hit single so they decided to use Stephen Hague. I don't know why they wouldn't let me do it, but I was fine about it, especially as it turned out so well. I have a huge amount of respect for Stephen Hague because he ended up doing exactly what I would have done. He said the demo of this particular track was so good that he was prepared to use it as a starting point. He did a few overdubs and mixed it again, but basically he left the spirit of it alone. Mind you, I can imagine what the label would have said if I'd told them I intended to use the demo! I think there might have been a sharp intake of breath at that point, but there you go."

Techniques

Street may not have a particular sound that he tries to impose on the projects he handles, but like all producers he has certain recording techniques that he likes to use in the studio. As a producer best known for his work with guitar‑based bands one might be forgiven for assuming that he's prescriptive when it comes to recording guitarists. But no — he isn't. The only thing he insists on is quality playing. After that, anything goes.

"You can have a guitar and an amp and one person can play it and it will sound completely different to how another person will sound when they play it. A lot of the sound does come from the player — it's the way they hit the strings.

"I think people forget that a lot of the time. It's no good saying you want to sound like Johnny Marr or whatever, because at the end of the day you've got to learn your chops. Johnny is a very tight player. He can plug a Fender Stratocaster into a Fender Twin and it will sound great because he has that touch. The same applies to Graham (Coxon) in Blur — he's an excellent guitar player and he knows what kind of sounds he wants to use."

With effects like distortion and certain delays, Street prefers the guitar player to use their own pedals because he finds that the sound you get when the effect goes through the amp and speaker is far better than any attempt at trying to re‑create it later on the desk. "It's better to put the effects on as part of the recording process unless you are really not sure about a particular part or about how much delay you want. I really do like it when the guitar player can get the sound they can hear in their head out of their amplifier because once you've got that sound it's wonderful when you push up the fader and it's there. You know you've got it right and you can't mess around with it later because you are making a production commitment. As a producer, making that kind of commitment is all part of learning how to do the job."

For miking guitars, Street normally uses a couple of dynamic mics, usually a Shure 57 and a Sennheiser 421. "I do sometimes try miking up further back but I generally find it starts making the amp sound very woody and roomy, which I don't like. If I want to add ambience to a guitar I'd rather do it at the mix, so normally I opt for close miking and if I want effects on the guitar I ask the guitar player to rummage through all the pedals and try and get it with them."

In keeping with his philosophy of letting the band create their own sound, Street feels that it is far better to let them choose the effects pedals and patches they want to use. He explains: "If they have been playing that particular song live with that particular patch for the last nine months, then they know that's the sound they want so why mess with it? Mind you, guitarists do have a tendency to put too much chorus on everything and I often have to tell them to take it off because I get tired of hearing it."

With acoustic guitars, Street usually tries out a couple of different mics before deciding which one to use. "I take each session as it comes — there's no particular set of rules as far as I'm concerned. I even use some of these great‑sounding DI inputs that some acoustic guitars now have.

"I also like the Rat distortion pedal — Graham uses that a lot — and I like the small Boss chorus pedal. I don't like the big digital units because I think they lack warmth. I've been using some interesting patches on the Eventide 3000 Harmoniser, which is great for some way‑out ambient sounds, but most of the time I do tend to use the Boss pedals and sometimes an SPX90 or 900 for chorusing. With bass guitars I tend to DI if I can get away with it, because all bass guitars are pretty much the same. If the strings are sounding really dull and it doesn't suit the song I get the bass player to put on some new strings so that the mid‑zing really cuts through."

Street observes that bands that have been touring before they go into the studio are, as a rule, much tighter. "Blur are one of the hardest working bands I've ever known — they never stop — so whenever we are in the studio they are really together."

For recording vocals, Street usually starts out with a trusty Neumann 87 or 47. When he is working with a singer for the first time he puts up two to see which sounds best. He also likes the dynamic hand‑held mics like the Shure 58. "They have a certain rock and roll edge that I like," he adds. "Bono uses them a lot to record his vocals.

"I like using proper EMT plates if possible. Failing that, a Lexicon plate setting. I always try and record the vocal with as little EQ as possible. The hardest thing is making sure singers learn mic technique. The mic can only take so much and even with the best compressor in the world I can't get round the sound beginning to break up if they are screaming too close to the edge of their range into a condenser mic. I try and get the singer to imagine he's singing into someone's ear and say 'if you're going to scream, just turn slightly away or back off a bit.'"

Street finds it easier to record vocals with singers that he knows: "With some vocalists, you know there is a certain mic that sounds right or you know there's a certain way they like to sing — maybe they sound better later in the evening than they do first thing in the morning or whatever. But I find that the way I work with most vocalists is pretty similar — I do four or five takes and just let them sing and then we comp up the best takes on another track. If there are still one or two lines that are not right we go back and sort them out. I like letting people sing all the way through because that way you get a better performance than you do if you try and deal with a song a verse at a time."

Street prefers to use a drummer whenever possible, but he isn't a purist and will use drum machines if the track demands that kind of approach — Blur's single, 'Girls And Boys', is a case in point. However, if he is recording a real drummer he tends to use a Shure 57 on the snare and 421s on the toms, with some ambient mics if the room sounds good. "I'm not a great lover of stone rooms though. I prefer wood live rooms to stone rooms. I do prefer using real drums where I can, because I find that after a while I get tired of the sound of programmed drums. If it feels good totally live then fine, I'm happy to use real drums. But even when you use real drums, some tracks do need more control to make sure they have a regular feel. In that situation I use a click track and my C‑Lab system. I'll run through the track on a click and if it sounds like it needs to speed up in a few spots, I'll programme a click track that speeds up at a particular bar so that the drummer can follow it.

Street prefers to use a drummer whenever possible, but he isn't a purist and will use drum machines if the track demands that kind of approach — Blur's single, 'Girls And Boys', is a case in point. However, if he is recording a real drummer he tends to use a Shure 57 on the snare and 421s on the toms, with some ambient mics if the room sounds good. "I'm not a great lover of stone rooms though. I prefer wood live rooms to stone rooms. I do prefer using real drums where I can, because I find that after a while I get tired of the sound of programmed drums. If it feels good totally live then fine, I'm happy to use real drums. But even when you use real drums, some tracks do need more control to make sure they have a regular feel. In that situation I use a click track and my C‑Lab system. I'll run through the track on a click and if it sounds like it needs to speed up in a few spots, I'll programme a click track that speeds up at a particular bar so that the drummer can follow it.

"I take each song as it comes. Sometimes I replace drums with samples if I find that the touch on the snares has been a bit up and down. I usually trigger through the Akai ME35T, which is a MIDI trigger device. I normally just record off tape through the Akai and record the note information of a snare or bass drum or whatever against SMPTE. Then I apply a minus delay using the C‑Lab, which pulls it forward and offsets it against the SMPTE. Then I can trigger whatever sample I fancy triggering. I don't totally replace the snare. Normally it will be just a bit of the original and if the drum fill doesn't feel right I'll try and swap over. It's a lot of messing around but it's worth it if it gets the sound that I want. Once you get used to using these particular machines it doesn't take too long — I find I can generally sort out a drum sound in half an hour.

"I use sampled drum loops occasionally because they are more funky and groovy than the programmed sound. On the last Blur album there were a couple of tracks where we got Dave (Rowntree) to play along to a click and we picked the best two or four bars and just looped it. 'Blue Jeans' was one of the tracks that had this treatment because we wanted that feel of it being relentless."

Home Life

Street doesn't have an extensive home studio but he does have some gear at his home, housed in a light converted loft room. At the heart of everything he has done over the last five years is C‑Lab's Creator. He also has his sampling and keyboard equipment and a few trusty guitars, including a Gibson 330 and a 1964 Fender Telecaster. For home recording he uses a Fostex quarter‑inch tape machine and no, he hasn't bought an ADAT yet — mainly because he does so little work outside a professional studio. The only piece of equipment Street feels is essential is his Creator — and the one thing he would buy if he had all the money in the world is The Manor studios. "That would make a nice home studio," he quips.

For the foreseeable future Street says he is happy producing. He adds: "I'm really enjoying life and things are looking great. I know I could go through a year or so when it's quiet, but that's OK because everything goes in cycles. It's sometimes hard fitting in a family life but ever since I've known my wife I've been involved in recording so she understands the hours I have to work.

"If I'm away too long the kids miss me so I try to take at least one day a week off, even when we are working in residential studios. Anyway I don't think it's healthy to work seven days a week non‑stop — try that and you soon get cabin fever!"

"A mic can only take so much and even with the best compressor I can't get round the sound beginning to break up if a singer is screaming into a condenser mic. So I try and get the singer to imagine he's singing into someone's ear. The strength of production is to know when something is OK. If it's not broken, don't fix it — there is so much truth in that saying."

Synths For Colouring

Street has a small collection of synths and samplers which he carts around with him, but he uses them only as "colouring". Notable are the Akai S2800, which he describes as a "great machine", and the Emu Vintage Keys and Proteus FX. "I really like Emu stuff. When we did the Smiths albums we always used the Emulator for the strings. I've yet to find decent string samples on the Akai — the Emulator is much better and so is the Proteus. But the machine I really like is the Vintage Keys. It's crammed full of vintage key sounds like Moogs and Hammonds and Mellotrons, which are the kind of sounds I really love. You can't beat a real Hammond B3 in the studio, but a lot of studios don't have them, so this machine is a good compromise and it comes everywhere with me."

Blur: 'Girls And Boys'

"This was one of those tracks that was truly programmed — it has the same chord progression going round and round, but it sounds great. The band demo‑ed it with a really disco beat and I thought it wasn't bad, but that if we were going to do it that way we should go the whole hog. It had real possibility as a dance track but to make that work we needed to programme it, and it gives the possibility of some really good mixes.

"So basically I went through all my dance samples on my Akai, got a sound sorted out — very 1980s disco — and programmed the drums and synth bass part and then just let the guys do their usual thing on top. Graham played some superb guitar and as soon as he put his guitar on it started sounding like Blur with some killer lines. Alex played a really cool bass part with some DI bass — he just likes to sit next to the desk and bounce up and down. With Alex, you have to say 'that bass line sounds really good so why don't you just repeat it a bit more before you go elsewhere.' He has lots of good ideas — sometimes too many and you have to pin him down.

"On this track I was triggering some Moog samples that I had on my Akai and every time it went to a particular chord I was just switching the programme on my Akai so it went from a round sound to a squeakier, acidy‑type sound which you can hear quite clearly. I know some programmers would have programmed it so that every time it came to that bar it would have switched over, but I thought sod that, and I just sat there and went through the track, going backwards and forwards with the data button. It was more fun — interactive recording! People expect the computer to do too much.

"As soon as I heard 'Girls and Boys' I knew it was a single. I said to Damon 'Top 10 single'. The minute we finished it I said 'Top 5' — and I was right. It was a very straightforward track to record. Damon did his vocals and then we all went in en masse and did the 'boys, girls' bit in the background. It was really a pleasure to record. When you have a track that's right it shouldn't be hard."

The Cranberries: 'Pretty'

"I love this song. It's one of my favourite tracks on the album and it was basically put down live. The band played it while Delores did a guide vocal in the control room and it was so good that we used the first take. We did the vocals again, but the bones of the track was already there.

"It was a case of Noel having the sound — a stereo guitar part that is sort of dryish on one side and with most of the effects on the other side. He was using an ART multi‑effects unit with a flanged reverb chorus setting that he has. He used that and it just suited that song. He wrote the song with that sound in mind so it was important to use it. He played that, and the drums and bass went down the line, and it was a real pleasure to record because it sounded so good. We just put a bit of organ on with a bit of delay on either side. It came together really quickly and beautifully. The best tracks are like that — they take the least amount of work."