Stuart Price’s refreshingly different approach to music–making has made him one of the most sought–after producers in the world.

Photo: Matt HoughtonMore than a decade on from his first releases as the wryly named Jacques Lu Cont with Les Rythmes Digitales, Stuart Price has firmly established himself as a songwriter, DJ, tour musical director and producer. Aside from his various remixes, for everyone from the Killers to Gwen Stefani to Coldplay (his reworking of their ‘Talk’ single bagging him a second Grammy in 2006, to sit alongside the one for his take on No Doubt’s ‘It’s My Life’), he’s probably best known for being Madonna’s chief sonic architect throughout this decade.

Photo: Matt HoughtonMore than a decade on from his first releases as the wryly named Jacques Lu Cont with Les Rythmes Digitales, Stuart Price has firmly established himself as a songwriter, DJ, tour musical director and producer. Aside from his various remixes, for everyone from the Killers to Gwen Stefani to Coldplay (his reworking of their ‘Talk’ single bagging him a second Grammy in 2006, to sit alongside the one for his take on No Doubt’s ‘It’s My Life’), he’s probably best known for being Madonna’s chief sonic architect throughout this decade.

Most recently, however, Price has overseen System, the fifth album by Seal. It’s a collaboration that in its latter stages took him to The Record Plant in Los Angeles, but had its beginnings in Logic files being sent back and forth via FTP from the singer’s home in Beverley Hills to the producer’s studio loft room in London.

System Of An Up

Today, Price sits in a suite in London’s upmarket Soho Hotel, explaining that the connection between himself and Seal came through Guy Oseary, formerly of Madonna’s record label Maverick and a neighbour of the singer.

“Guy called me,” he recalls, “and said ‘Look, I’ve got a really good song that Seal’s done, but it’s not in the right direction. If you like it, have a go at it.’ It turned out to be what became the first single, ‘Amazing’, just an acoustic guitar demo of it. Twenty–four hours later, I’d produced it and sent it back. Sometimes it just happens like that if the song is just so obvious to you, how it should be. I had a feeling in my head for what I thought a Seal record in 2007 should be. He’s a rare artist in that Seal and technology go together. He’s got a way of having a big voice on electronic music without sounding naff.”

For his part, Seal was more than happy with the results, and the remote production arrangement stuck, the singer uploading rough tracks one by one and Price reworking them, until it became apparent to both parties that the time had come to actually meet.

“I remember saying ‘I don’t want to get on the plane until we’re 10 songs in!’,” Price laughs. “Seal had always said to me ‘Surprise me,’ when he was sending me tracks. And the way to do that was to turn them around and just completely recontextualise them. In all honesty, I think he was stuck with them. I didn’t change the songs much but what I did do was load up the session, hit Solo on the vocal track, and then I’d just sit there reworking music around it, underpinning his melodies with different chords.

“If you’re in a room with someone and you’re creatively destroying their song, they might have a word or two to say about it. But this way you can work through something and come back with your take on it and they can respond objectively to it. And that’s how it worked — he’d send me songs, I’d do my thing to them and send them back. So effectively, when we got together in Los Angeles, it was like a big blind date. I said ‘I’ll be wearing a pink carnation, standing by the SSL.’”

Confessions Of A Bedroom Producer

Commercial studios aside, Price admits that his comfort zone in terms of his work is his home setup, being clearly proud of what he calls his “bedroom studio mentality”. Originally based in his loft at home, where he did much of the work for Madonna’s Confessions On A Dancefloor album, his equipment was relocated to his basement when he moved. Now, as he’smoving house again, the studio is destined for the loft once more. “It’s like the Upstairs Downstairs of the recording world,” he grins.

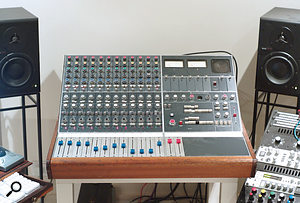

Centred around a G5 Dual 2.8GHz currently running Logic 7.2 (he’s in the process of updating to version 8) with a MOTU HD192 interface, Price uses a 12:2 Neve Melbourne mixer for much of his tracking and some of his mixing. “It’s like a BCM10, but with the 33–series EQs,” he explains. “The outboard is fairly standard: Urei 1176s, an Avalon 737 pre, a Neve 1084 pre. In my travelling setup I use the Apogee Symphony and the AD16s and DA16s, which I really like. But that’s if I’m going to work at The Record Plant or somewhere.”

In terms of synths, Price’s favourites include his Clavia Nord Lead 3 (“I’ll go to the grave clutching that”) and the decidedly old–school Yamaha TX7 (module version of the DX7) and Casio CZ101. “I really cut my teeth using those, and I’ve carried on using them ever since. Those were all I used to be able to get my hands on because you could pick them up for, like, 50 or 60 quid. I think what’s interesting with all those older, early digital synths is that the D–A conversion in them was so rudimentary that it really gave them their own tone, in the same way that a guitar has its own tone. I think the generic sound of a lot of soft–synth–based music is down to the fact that you’re relying on the same D–A from whatever your card is. That’s not to say there’s anything wrong with it, but I want a fairly wide tone palette for my music and I get that, I think, from having various pieces of equipment that really impart their own character.”

An enemy of the ongoing march of preset production, Price advocates a rather more haphazard approach to the process of achieving character in his music. “My synths are never racked up or made to look tidy,” he says. “They’re always leaning up against the wall, so that they can be dragged out onto the floor in the middle of the room and the cable goes in. I don’t mind if the SH101’s going straight into the Neve or if it’s going in via a guitar Pod or going direct into the soundcard. I don’t really mind — it’s whatever cable’s nearest. And then you stumble upon the area of chance, which is ‘Well, I wasn’t planning on plugging this synth into the guitar amp, but because the cable’s there I did it and it was miked up and I recorded it.’ And you start getting happy accidents. You just want to know that you can drop Logic into track arm and go for it. I think that’s a really important part of the creative process.”

Unsurprisingly, then, he doesn’t use soft synths and favours using his own sample library in Logic’s EXS24. Plug–in–wise, he finds he continually returns to the PSP range and the Universal Audio UAD1 card. “The Waves stuff I just never got into,” he states. “It’s probably really good, but I’ve just never really used it on something and gone ‘That’s exactly what I’m looking for.’ Having said that, on Seal’s album I used the Waves Renaissance Vox, which I’ve got to say was pretty bloody amazing actually, so I might retract that statement! But my point is, until you’ve found something that’s worked for you, everything’s rubbish. There’s no point in being a sort of plug–in collector. I think you hold on to the things that you love. And a lot of them are free, like the Ohmboyz Fromage filter, it’s a classic. It’s something that instantly gives you what you want.”

Mostly Mistakes

A 12–channel Neve mixer is central to Price’s studio.System was completed in an enviably swift period — four weeks of what Price calls “international trading” of files and then four weeks in Los Angeles refocusing on the vocal performances and tweaking the album’s tracks before mixing. The producer chose to return to The Record Plant’s SSL1 room with its 9080J Series desk, because he’d previously worked there on Madonna’s Confessions On A Dancefloor. But, highlighting his desire for a more home–made approach, Price insists on re–arranging the studio’s furniture to lend the working environment a cosier, more creative feel. “I always have them take the couch out at the back of the room and I set up my programming rig there. It gives you and the artist somewhere to work that’s a corner of the room, so it’s a little more intimate. From a singer’s point of view, walking into a studio where there might be you, an engineer and assistants around, it’s not very welcoming. It’s like someone saying ‘Now, you, artist, be brilliant.’ That’s not conducive to getting good results out of someone.

A 12–channel Neve mixer is central to Price’s studio.System was completed in an enviably swift period — four weeks of what Price calls “international trading” of files and then four weeks in Los Angeles refocusing on the vocal performances and tweaking the album’s tracks before mixing. The producer chose to return to The Record Plant’s SSL1 room with its 9080J Series desk, because he’d previously worked there on Madonna’s Confessions On A Dancefloor. But, highlighting his desire for a more home–made approach, Price insists on re–arranging the studio’s furniture to lend the working environment a cosier, more creative feel. “I always have them take the couch out at the back of the room and I set up my programming rig there. It gives you and the artist somewhere to work that’s a corner of the room, so it’s a little more intimate. From a singer’s point of view, walking into a studio where there might be you, an engineer and assistants around, it’s not very welcoming. It’s like someone saying ‘Now, you, artist, be brilliant.’ That’s not conducive to getting good results out of someone.

“The record–making process is 95 percent mistakes,” he reckons. “And mistakes are embarrassing. You’re just waiting for the five percent of magic to happen. And the more comfortable you can make someone feel, the greater the chance that that’s gonna happen. So I always have the setup at the back of the studio, monitoring and everything. Effectively you’re working in that little world, honing, refining, re–recording, cutting stuff. There’s a good separation that happens when you say ‘Right, let’s just spend half an hour putting a mix down.’ You go and sit in a different point in the studio — slightly different perspective, slightly refreshed. You make better decisions about where it’s going. Seal has a good phrase — ‘The record will sound like the time you had making it.’ And I think that’s a really good point.”

The Spontaneous Approach

It was exactly this artist–friendly approach that attracted Madonna to Stuart Price as producer of Confessions On A Dancefloor. The pair had first hooked up when Price was enlisted as keyboard player for the star’s 2001 Drowned World tour, going on to co–write ‘X–Static Process’ on 2003’s American Life album, before becoming the musical director for the following year’s Re–Invention world jaunt. Preliminary sessions for Confessions were carved out between her regular producer Mirwais and Price, though Madonna found herself gravitating more towards the latter as the project progressed.

Stuart Price’s home studio is set up to favour happy accidents, with synths stacked against walls rather than neatly racked. “One of the reasons I think she enjoyed it was because it was like how she’d worked at the start of her career,” he says. “It was a bit more like going round to a DJ’s place where there were tracks going around and we could come up with an idea pretty quickly and get something going. It was quite spontaneous like that. Normally I’d have had a track that I’d been working on, she’d come round and listen to it and we’d maybe make some adjustments. Then she always liked to go home and come up with her bit, her idea and her hooks. Even if it wasn’t completed lyrics, she’d have ideas of what she’d want to do. Then she’d come back round to the loft and we’d just work together cutting the vocals and doing it like that.

Stuart Price’s home studio is set up to favour happy accidents, with synths stacked against walls rather than neatly racked. “One of the reasons I think she enjoyed it was because it was like how she’d worked at the start of her career,” he says. “It was a bit more like going round to a DJ’s place where there were tracks going around and we could come up with an idea pretty quickly and get something going. It was quite spontaneous like that. Normally I’d have had a track that I’d been working on, she’d come round and listen to it and we’d maybe make some adjustments. Then she always liked to go home and come up with her bit, her idea and her hooks. Even if it wasn’t completed lyrics, she’d have ideas of what she’d want to do. Then she’d come back round to the loft and we’d just work together cutting the vocals and doing it like that.

“I mean obviously there’s no vocal booths in the loft, so it’s very much both on headphones and going for it. And if the doorbell rings, then the doorbell’s on the recording. It was that bedroom–studio mentality again, which I think was one of the most spontaneous parts of that record.

“The mics were a combination of Sony C800G and Rode NT2,” he adds. “About 60 percent of the vox were on the Rode. It’s not a mic that particularly shines on many things, but it was just an example of the right mic in the right room on the right voice. The Rode was used on any tracks that had a very direct, compressed vocal approach, and the Sony for tracks where the vocal direction was one of more body. EQ was UAD1 Pultec. Both mics went through an Avalon 737SP preamp to Urei 1176 [compressor] to Neve 33129 [EQ] then to a Lucid AD9624 [A–D converter].”

In reworking Madonna’s old masters for tour productions, Price discovered that this kind of home studio spontaneity figured even in the singer’s early work. “You solo vocal tracks on ‘Into The Groove’,” he says, “and you hear cabs going by in the background and that the speakers were on in the room as well. It’s just reassuring. Sometimes you can really stand in the way of a good vocal take by obsessing over a ringing at 200Hz. Paramount importance is performance. Unless you’ve got serious problems in your signal chain, there’s not a lot that you can’t take care of later. I’m not saying it’s the best way to do it, but if want to get the best performance out of an artist or a band, don’t let them get bored while you say [he puts on a nerdy tone] ‘I’ve got a few different XLR cables I’d like to try out.’ It’s not the time to do it.”

Live Band, DJ Mix

As their working relationship has developed, Madonna has allowed Price free rein with her music. For 2006’s Confessions tour, the producer employed risky, if innovative technical methods in his musical directorship, by attempting to bridge the gulf between the studio and the stage. “I always saw there was a great disparity between studio music and live music,” he states. “And I also thought that what we were doing was dance music, so by its very nature, the fact that we’re doing this with a band, is that a contradiction there? So I wanted to approach it in a different way.

As well as producing most of Confessions On A Dancefloor, Stuart Price also used his role as musical director on Madonna's tours to reinvent the relationship between live band and DJ. “My on-stage setup for the Confessions tour was a Logic rig using the RME MADI Hammerfall cards. There was the band on stage, but all their lines would go via a stage box into my rig and Logic actually became the mixer for the show. I could set up my plug–in chains, have various instruments side–chained off different instruments, and I had a new session for each song with a key command to switch to it. So you had a total recall of each song. Then it came out stereo, left and right, into my Pioneer DJM 600 mixer. I had one stereo fader for the whole mix, which was then going to my filters, my global mix flangers and stuff like that.

As well as producing most of Confessions On A Dancefloor, Stuart Price also used his role as musical director on Madonna's tours to reinvent the relationship between live band and DJ. “My on-stage setup for the Confessions tour was a Logic rig using the RME MADI Hammerfall cards. There was the band on stage, but all their lines would go via a stage box into my rig and Logic actually became the mixer for the show. I could set up my plug–in chains, have various instruments side–chained off different instruments, and I had a new session for each song with a key command to switch to it. So you had a total recall of each song. Then it came out stereo, left and right, into my Pioneer DJM 600 mixer. I had one stereo fader for the whole mix, which was then going to my filters, my global mix flangers and stuff like that.

“The cumulative effect was that you started to integrate a live band into the studio production world. People would be watching the band and they’d start to connect when they suddenly saw me sweeping the filter down on the whole mix, even though they’d be watching this drummer play a live kit. It was imposing the DJ club dynamic onto live music. ‘Like A Virgin’ would be going along — verses I’d pull the volume a bit, roll all the bass off two bars before the chorus and when the chorus came in, I’d crank the gain and stick it all back up. It gave you a dynamic control over the music that a DJ has that normally a front–of–house mixer won’t have.”

The input chain used on Madonna's Confessions On A Dancefloor involved Price's Neve mixer, Avalon 737SP preamp, Urei compressor and Lucid A-D converter. Also visible here are a Smart Research C2 compressor and GML EQ.The big question, of course, being: did the system ever crash? “No. I have to say that the rig was completely rock solid. The guys from Apple came down to see one of the shows and they said ‘So how are you using Logic?’ And I said ‘Well, basically, I’m using it as a mixer and there’s 22 sessions open at the same time.’ They went a bit pale and looked a bit worried and said in this German tone ‘We didn’t really design Logic to be used in this way.’ The only time we ever had a problem was with the Xtend–it cables going down. Worryingly, there were a couple of times when we just lost USB in the middle of the show! So I’m unplugging the mouse and plugging it back in

The input chain used on Madonna's Confessions On A Dancefloor involved Price's Neve mixer, Avalon 737SP preamp, Urei compressor and Lucid A-D converter. Also visible here are a Smart Research C2 compressor and GML EQ.The big question, of course, being: did the system ever crash? “No. I have to say that the rig was completely rock solid. The guys from Apple came down to see one of the shows and they said ‘So how are you using Logic?’ And I said ‘Well, basically, I’m using it as a mixer and there’s 22 sessions open at the same time.’ They went a bit pale and looked a bit worried and said in this German tone ‘We didn’t really design Logic to be used in this way.’ The only time we ever had a problem was with the Xtend–it cables going down. Worryingly, there were a couple of times when we just lost USB in the middle of the show! So I’m unplugging the mouse and plugging it back in

“We were running a G5 with another G5 as a back–up that we could switch over to, which we never needed to do. There’s certain quirks to the way you can use Logic that are great and I think when you combine those quirks with a producer on stage that wants to take the music further, the results can be quite exciting. What’s great is a lot of live acts now are using Ableton and stuff, so there’s that integration going on in a studio/live hybrid.”

Parallel Vibes

When it comes to studio mixing, trial and error and his apparently characteristic level of questioning has found Price developing a similarly unusual approach. “It is quite unusual and it is quite backward as well,” he jokes. “It was answering the bigger question: should I be mixing in the computer? Or should I be mixing on the desk? To me the answer was both. So now I duplicate the mix I’m working on. Let’s just say I’ve got 16 channels of subgroups. I pull them out on the patchbay so there’s another 16 exactly the same. The first 16 will be going to perhaps a bus compressor and EQ, the second 16 won’t, they’ll be dry and unaffected. It just means for pushing into choruses and stuff, if I want them to have a little more clarity, I’ll bring up the dry group more. Whereas with the verses or the bridges, if I want them to sound a little more bouncy or lush, I’ll lean more on the compressed group. It’s like a sort of parallel compression idea but with individual control of the various stems.

“I don’t like to take an overly methodical, technical approach to mixing. I just like the vibe factor to be high. I save completely in–the–box mixing for if I’m travelling or working somewhere and want the convenience of it. That’s great because it means that we could sit in this room now and have a really wide palette of things available. But if I’m at my studio or if I’m at a studio where I’m using an SSL, I’ll use this mixing route, ’cause I think you’re getting the best of the analogue and digital flexibility.”

Clearly something of a musical Renaissance man, Price feels that each of his different roles benefits the other. “I always try to blur the boundaries between being a DJ, a remixer, a producer, a writer. They’ve all got something in common. So why have this distinction between the different departments? Why not combine it all into one? I’m taking what I know as a DJ and applying it to remixing. I’m taking what I know about remixing and applying it to production. And in that sense it just becomes a big melting pot of skills. Applying those things across the board for an artist is a good thing to do.

“With Seal, for example, I could rearrange his music, I could do the remixes for the singles and then I’m gonna help him with his live tour as well. Beause I just don’t want to take my producer hat off at the end of the day and say ‘Right, well, your record’s done, good luck.’ There’s a vision that was started off there that needs to be executed. And I think seeing that through with Seal, and his back catalogue as well, and re–contextualising it, is exciting.”

Push Yourself

When the 16–year–old Stuart Price was messing around with synths and primitive sequencers at home, did he ever think that he’d find himself in his current position? “Well, I was very determined,” he says. “But I think one thing that was able to be proven was that working on music in your bedroom as a 16–year–old versus working with Madonna or Seal or being on stage in front of 100,000 people... the gap is not that wide. There’s a lot of experience that needs to happen to give you that kind of confidence. But it’s not like a far–off universe working at that level.

“I mean, don’t get me wrong,” he continues, “there’s a lot to learn, there’s a lot to understand. The thing with Madonna was that because we were under such tight deadlines for a tour with two months of rehearsal to get 25 songs ready, I just got used to making very quick decisions.

“But I was that kid sitting in my bedroom, learning. I had to push myself and say you’re never good enough, you have to be better. I think one of the things that’s worrying is that because the technology’s so accessible these days and so available, there’s a lot of well–produced shit out there. Which didn’t used to necessarily be the case. And I think it’s really important to know that without the song or the hook, you don’t have something good. And learn to work quicker and quicker. It’s the old adage: work cheap and work fast. Because there’s a bigger chance that you’ll come across something good.”

Finally, then, can Price see a thread through his work and, perhaps more importantly, any indications of where it might lead? “Well, when I started to listen to pop music, things like Pet Shop Boys,” he says, “it was always bands that employed technology in an exciting way that attracted me. And I have ended up working with people that do have electronic sympathies, shall we say.” He pauses, and you can almost see the light bulb go on above his head. “Good album title, that.”

Remixing The Emotions

Where his remixes are concerned, Stuart Price says he sets the bar high for himself. “You push yourself as hard as possible and you try and maintain a high standard threshold. But I’d also in the same breath say that I’m very dissatisfied musically and I think that dissatisfaction is a kind of fuel for future endeavours.”

Has he toiled for weeks on certain remixes while others have only taken hours?

“Well, funnily enough, the one that took the longest was the one that won a Grammy, Coldplay’s ‘Talk’. My approach to remixing is always to start from stripping back to the vocal, because for me, remixing is less about the new beats or the effects or sounds and more about the new emotion you’re putting into it. I always like to make a happy song sad or a sad song happy. That’s why it always starts with stripping down to the vocal and listening to it, so within those parameters, you start to think of a new harmonic framework for the underlying chords. I’ll build it up on the harmonic basis first, by which point you normally find that the beats are starting to suggest themselves.”

Seal Singing

Seal: “He’s got a way of having a big voice on electronic music without sounding naff.”In The Record Plant, Seal and Stuart Price established a streamlined approach to recording the final vocal tracks for System. Price would work on the track in the morning, then Seal would arrive and they’d listen through to it, as the singer reworked his lyrics. Forty–five minutes or so later, he’d cut the vocal, doing three takes in quick succession, which the producer would then comp and tweak.

Seal: “He’s got a way of having a big voice on electronic music without sounding naff.”In The Record Plant, Seal and Stuart Price established a streamlined approach to recording the final vocal tracks for System. Price would work on the track in the morning, then Seal would arrive and they’d listen through to it, as the singer reworked his lyrics. Forty–five minutes or so later, he’d cut the vocal, doing three takes in quick succession, which the producer would then comp and tweak.

“Nine times out of 10, he’d then come back in, hear the comp and go ‘You know what? Give me one more go.’ And he’d have observed and listened to what he did and how the comp had worked out and he’d be making his own internal notes as to what he’d done. Then he’d go in and do take four or five and he’d nail it. That speaks volumes about just how in control of his voice he is, and his understanding of it as an instrument.”

When it came to microphone choice, Seal and Price swapped between the Sony C800G and a Neumann U47 FET, depending on the requirements of the track. “We didn’t use any compression until after the event,” says the producer. “Seal’s understanding of the studio process — I’m sure, by and large, due to years spent with Trevor [Horn] — is just exemplary. That even goes through to things like his mic technique. He’s so aware of what he’s looking for in a mic and what he’s looking for in his voice that he was able to say ‘I wanna try this on the 47.’”

In the wake of the Seal sessions, Price has become a huge fan of Melodyne, which he used for far more than vocal tweaking. “The flexibility in it is pretty astounding,” he enthuses. “We were also using it for the creation of harmony parts and for matching up double tracks. But then we started using it a lot on other instruments and on percussive parts. It offers a level of mangling which far surpasses its fairly basic interface. The most incredible thing is its timing manipulation and the way that it allows you to re–time vocals. As part of a writing process, it’s really good if you’re thinking ‘I wonder what it’d sound like if we do this.’ And instead of having to go and recut it, you just move it and quickly decide whether it works or not.”