Apple iPhone 6s Smartphone

There’s an amusing outtake from venerable journalist Walt Mossberg’s video review of the iPhone 6s for The Verge: he’s using the phone and exclaims “it’s f**king fast” — and it really is. The iPhone 6s is powered by Apple’s A9 system-on-a-chip, featuring a dual-core 64-bit ARM architecture running at 1.85GHz, and, for the first time on an iPhone, 2GB of memory. Running Geekbench 3, the A9 has a multicore score of 4433, which is pretty remarkable compared to the iPhone 6’s 1.4GHz A8 chip that scored 2908. In fact, the A9 narrowly beats the A8X featured in the iPad Air 2, which scored 4418 — and that’s a tri-core chip!

While this increase in performance is a big deal, it’s not the most impressive thing about the iPhone 6s. The Apple Watch introduced a feature called Force Touch, where you could tap the screen normally to perform one function, and press it a little harder to perform another. A new technology implemented in the iPhone 6s called 3D Touch takes this further by measuring how much pressure is applied to the screen, making possible a host of new user interface interactions.

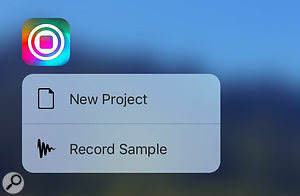

The simplest of these interactions are Quick Actions, which are basically a way to get at regularly used functionality with fewer taps. On the Home screen, apps can display a list of relevant actions when you press an app icon and then apply a little more pressure. One of my favourite examples was Shazam, where you can use Quick Actions to start Shazam listening right from the Home screen.

There are also two interactions Apple term as Peek and Pop. If you’re in Mail browsing your Inbox and press a little harder on an email item, you can ‘peek’ into the email to get a preview without opening it. By ‘poking’ a little harder, the email will be opened. To give you haptic feedback when using Quick Actions, Peek and Poke, the iPhone 6s has a Taptic Engine, which was also introduced on the Apple Watch. As an example, if Quick Actions aren’t available for an app, the phone will tap three times (instead of once), and you’ll notice the effect is remarkably more pronounced than the vibrations of earlier phones.

While these interactions might not seem that interesting for music and audio apps, they merely scratch the surface of what’s possible with 3D Touch, since it’s possible for apps to detect the pressure of each touch on the display. One of the first apps to take advantage of this was Bismark’s bs-16i, where the on-screen keyboard can now offer aftertouch, and I imagine other developers will implement something similar, maybe using 3D Touch for velocity sensitivity rather than the accelerometer. Native Instrument’s iMaschine 2 also supports 3D Touch, providing Quick Actions for the app icon and the app’s on-screen pads, and also using it to control the rate of note repeat.

Another new app that supports 3D Touch is Miditure. This is a MIDI controller app that offers two pages of controls: one with nine pads, each of which can trigger up to four notes, and one large X-Y controller. With 3D Touch, each pad is velocity sensitive with configurable aftertouch, and the background glows to reflect the pressure being applied. The X-Y pad effectively becomes an X-Y-Z pad, since you can now control three parameters simultaneously. It’s a neat example of how 3D Touch can add quite literally an extra dimension to music and audio apps, and I can’t wait for the day when this technology, hopefully, comes to the iPad.

As is usually the case with s-iteration iPhones, the iPhone 6s is almost physically identical to its predecessor. I say almost because it’s imperceptibly thicker and heavier — 7.1 versus 6.9 mm and 143 versus 129 grams — although you’ll struggle to notice. The iPhone 6s also retains the same storage tiers as the 6 — 16, 64 and 128 GB — and, as many people have noted, 16GB is a ridiculously low amount of storage for a device with so much functionality.

If you have a pre-6 iPhone, upgrading to the iPhone 6s will blow you away. And even if you have an iPhone 6, you may have a hard time resisting the increased performance and 3D Touch. As for those who don’t yet own an iPhone, given the quantity and quality of the music and audio apps available, this is quite simply the best mobile device for making music. Mark Wherry

From £539

From $649

Ten Kettles Waay

Music Theory Educational App for iOS

Inspired by the spirit of ’70s punk, I started making music by buying a mail-order guitar and teaching myself to play with the help of a selection of books and cassettes. As a result, there are more holes in my formal musical education than there are in a string vest, and only slightly fewer than in the plot of Skyfall.

The Waay app from Ten Kettles — who gave us the Hear EQ ear-training app that we reviewed in July 2014 — aims to help people like me to develop their practical music-theory knowledge. Ten Kettles explain that Waay’s mission is to teach music theory for song writing, arguing that it is often taught to us just so we can pass a music theory exam in school. A free first course, called Melodies, comes with the app, but further courses must be bought as in-app purchases.

iMaschine 2 implements Quick Actions on the Home screen.Inside the app the pupil is met with a panel displaying their name, customisable picture icon and points and stars counters. Points are earned for correct answers and stars are accumulated for passing lessons. Completing a lesson flawlessly and within the time allocated can earn three stars, whereas a basic pass is worth one. Also on the panel is a Progress button, which brings up a graph showing how things are going in a bit more detail, plus a list of all the courses that the user has purchased. The rest of the screen is taken up by a menu of course components, through which the pupil can scroll up and down to access the one they want to look at. It’s easy to skip sections, but it’s not a bad idea to start at the beginning where there is an introduction to some basic concepts like flats, sharps, natural notes and steps.

iMaschine 2 implements Quick Actions on the Home screen.Inside the app the pupil is met with a panel displaying their name, customisable picture icon and points and stars counters. Points are earned for correct answers and stars are accumulated for passing lessons. Completing a lesson flawlessly and within the time allocated can earn three stars, whereas a basic pass is worth one. Also on the panel is a Progress button, which brings up a graph showing how things are going in a bit more detail, plus a list of all the courses that the user has purchased. The rest of the screen is taken up by a menu of course components, through which the pupil can scroll up and down to access the one they want to look at. It’s easy to skip sections, but it’s not a bad idea to start at the beginning where there is an introduction to some basic concepts like flats, sharps, natural notes and steps.

Each lesson is given by a voiceover which is accompanied by on-screen subtitles or visual examples of what’s being discussed. If the information arrives too fast, however, the lesson can be paused and wound back using the progress bar that’s displayed at the bottom of the page. Between the lessons are the exercises and tests that earn the successful pupil stars and points. There’s no limit to the number of times a test can be taken, but the app is clever enough to generate a new set of questions each time so that things don’t become too predictable.

Miditure indicates how much pressure is being applied to each pad by adjusting the brightness of a given pad.Generally speaking, the app takes the view that the main thing a songwriter needs to know is the relationship of the notes. For this reason, it starts by developing the pupil’s knowledge of note intervals, before moving on to explain tonics and major and minor scales. Scales are seen as essential building blocks by the Ten Kettles team and pretty much all of the lessons that follow can only be completed if the pupil has grasped how they work. Next, the Circle of Fifths is introduced, and a little later the app tackles the Circle of Fourths as well.

Miditure indicates how much pressure is being applied to each pad by adjusting the brightness of a given pad.Generally speaking, the app takes the view that the main thing a songwriter needs to know is the relationship of the notes. For this reason, it starts by developing the pupil’s knowledge of note intervals, before moving on to explain tonics and major and minor scales. Scales are seen as essential building blocks by the Ten Kettles team and pretty much all of the lessons that follow can only be completed if the pupil has grasped how they work. Next, the Circle of Fifths is introduced, and a little later the app tackles the Circle of Fourths as well.

For this review I was also sent the second course, called Chords, which would normally be an in-app purchase. It takes the principles learned in the Melodies course and applies them to chord sequences, and also reveals a ‘Magic Formula’ for choosing chord progressions. This, it says, is one of the biggest things you can learn as you start bringing music theory into your songwriting.

Much as I liked the app for it’s simple, straightforward approach, I don’t think it’s for me. I tend to think in terms of note patterns and positions and have come to know where the notes and chords are without ever thinking much about what they are called. I also prefer to discover ideas through exploration rather than applying formulas. However, everyone’s brain works in a different way, and I think that anyone who takes a more mathematic approach to things and is great at remembering formulas and data will find it suits them very well. Tom Flint

£3.99

$4.99