With the latest version of their unique 'object oriented' DAW, Magix are targeting both mastering and recording engineers.

This is the third incarnation of Samplitude I have reviewed for Sound On Sound, having previously looked at version 10 in March 2008 and version 9 in 2007. In both of these other reviews, there were so many new features to cover that I was forced to give the core functionality of the program rather short shrift. This can easily happen when a particular program goes through a series of upgrades, especially when the new version is fully backwards compatible with all the previous incarnations. (Backwards compatibility is highly desirable, but for technical reasons it is not always possible. At our studio, the hardware DAW we use for classical editing is now at version 6: this is entirely compatible with version 5, but both 5 and 6 projects require special — irreversible — conversion to be read by a version 4 machine, and if you have version 3 you'll get precious little product support, pitying looks from your colleagues, and potential scorn from your clients.)

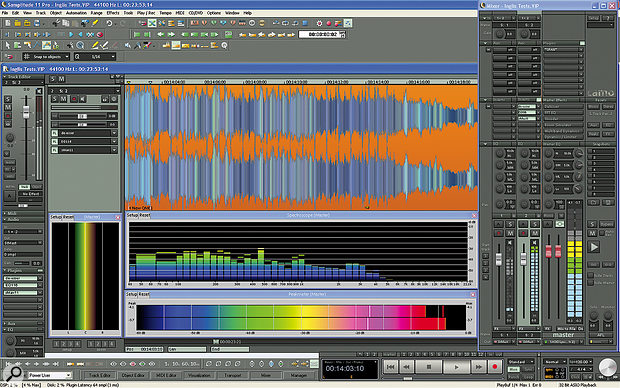

Samplitude is, however, a very fully featured DAW, so I thought it was probably a good idea for us to be reminded again of some central features of the program that are quite unique to it, and so which might be judged to set it apart from the competition, before I start looking at the incremental changes in the new version 11.

In my opinion, the two features that separate Samplitude from most of its similarly priced competitors are what the manual call its "object–oriented audio editing”, and the very high quality of its included signal processors, so I will discuss these first. I ended one review by saying that Samplitude had just about everything you could need for recording, editing and mixing a project, and it is now clear in version 11 that the programmers want the final stage of music production to be taken seriously as an possibility as well, thanks to the inclusion of two new mastering processors.

Samplitude Objects

In most halfway‑decent modern DAWs, various sections of a single track can be defined and separated from the rest by making a couple of cuts. And in most DAWs, of course, these are non‑destructive, virtual cuts: they refer to the underlying audio material without actually changing it. The part so defined has different names in different programmes (in SADiE and Pyramix, for instance, it is called a 'clip'), but in Samplitude it is simply called an 'object'. In most DAWs, these parts can be manipulated in various ways — they can, for instance, be moved along, or between, tracks for editing — but the processing that can be applied to them at this level, independently of what might be going on in the mixer, is relatively restricted. You can usually apply gain changes and normalisation, and also processes such as plug‑in effects or time‑stretching, but these are typically applied semi‑permanently.

The uniqueness of Samplitude (and its bigger brother Sequoia) in this respect is simply that it greatly expands the number and type of operations and processing that can be applied to individual objects. As the screen to the right shows, these range from the indication of various object parameters such as start and end time and length, through the ubiquitous gain‑change and fade‑editing operations, to separate inclusion of the object on the aux bus, adjustment of pan and stereo image, loop control, colour and other properties such as locking, freezing, and bypass, pitch‑shift and time‑stretch processing, a switchable four‑band EQ, and a virtual rack for the insertion of up to six processing plug‑ins. Both VST and Direct X plug‑in standards are supported, as well as the native plug‑ins that are included within Samplitude itself, of which more presently.

Now, in my opinion this is quite a marvel, and because no other DAW can operate in quite the same way (though some come functionally pretty close: in Pyramix, for example, you can drag and drop individual mixers from a library onto selected clips — see my review in SOS September 2008, online at /sos/sep08/articles/pyramix6.htm), it often does prove to be a deal‑breaker. I know of an increasing number of mixing and mastering engineers over the past two or three years who have moved to Samplitude or Sequoia from bigger‑name DAWs that, until then, had been more visible in the market, but as yet I've not met one who has moved on or moved back.

Objects In Action

Like a lot of mastering engineers, I use a combination of analogue outboard processing,and both outboard and plug‑in implementations of digital processors. I'll describe my entire chain first — of course, not every element of this chain is used on every track! — and then show how the object‑based approach works with it.

The chain starts, of course, in the DAW (here, Samplitude): it is sent out of outputs 3/4 to a Weiss digital EQ, then via a DCS converter into the analogue chain, which comprises Maselec and Pendulum compressors and Maselec and Thermionic Culture Pullet EQs. The A‑D converter out of this chain acts as the master clock for the whole system, and the digital signal is then sent to a TC System 6000 for further processing, such as de‑essing, EQ and limiting, finally captured back in Samplitude through inputs 1/2 on my interface.

Generally, each part of the chain has a specific task. The Weiss, especially in dynamic mode, is a superb corrective tool and so does most of the surgical work (mainly subtractive: cutting boom, tizz and glare) before the signal goes into analogue, and although the Pullet EQ has a wonderful 'mid‑mud‑clearing' ability, along with the Maselec EQ and other analogue processors, its main task is to massage and enhance the signal. The analogue EQs are generally pre‑compression, so as the last processor in the System 6000 is the brick‑wall limiter, the digital Massenburg EQ in the System 6000 is post‑compression but pre‑limiting.

The general philosophy here is that each processor doesn't do an awful lot to the signal in itself, but that the entire chain does. So although there may be a few dB of filtering and a few dB of gain reduction overall, each unit has hardly exerted itself very much at all. I have found that this piecemeal approach allows each part of the chain to play to its strengths: when EQ'ing, low frequencies here are better served by the digital processors, but the Pullet has heavenly mids and the Maselec wonderful upper‑mids and a very special 27kHz(!) high‑shelf. For gain‑reduction duties in particular, it seems highly advantageous to the final sound to have a series of mild compressors working throughout the chain, rather than one big one at the end.

This 'shared duties' view extends even to the limiting that is applied. As I have said, the final processing applied to signal before it is recaptured in Samplitude after the outboard pass is limiting in the System 6000. But by the time it has reached here, the signal has often been mildly compressed twice, and so getting the signal to a healthy level might then involve pushing the input gain, but still with the limiter removing only the very tops of the remaining loudest peaks. In the naming system we use here, this file is called the 'NLM' or non‑limited master — the signal has been limited, but it has not been squashed, and it has a healthy enough level for evaluative listening and represents the optimal sound that we can achieve. If the client then wants it to be louder, then at least he or she has a benchmark for evaluating the sonic costs of that loudness.

The plug‑ins, meanwhile, can be used at either the beginning of the chain on the source material, or at the end of the chain on the captured result of the processing, and this is where Samplitude's object‑based approach comes into its own in my system. At the beginning of the processing, I might actually want to use a plug‑in EQ in addition to the outboard Weiss — again working on the philosophy that each processor doing its own thing makes for a better overall sound — and at the end, after the client has heard the 'NLM' version, I am often asked to add another level of limiting, which in itself can then create a need for some further minimal EQ changes (limiting can easily affect balance: the 'Where did the bass and snare go?' syndrome).

All of these tasks are made so much easier by being able to insert and control plug‑ins at object level. For example, suppose I have an 'NLM' file that the client has approved but wishes to be just a dB or so louder: if I had to re‑run the whole chain for each song, or just make changes in the project mixer if I was using that to host the plug‑ins, that would take an inordinate amount of time for a whole CD. But as I can make that adjustment for each individual object and then bounce it all down in non‑real time, what could have been a few hours' work can be done in a matter of minutes. In other words, because each object has its own EQ and limiter, I can make individual adjustments to them at object level, and then run the final processing and burn of a whole CD's worth of material in non‑real time, without having to do any fancy automation moves in a mixer or elsewhere, and in an entirely controllable and very easily recallable manner. That is a very good thing!

Included Plug‑ins

Having discussed the deep flexibility of the control of plug‑ins provided at the object level, we should now turn to those plug‑ins themselves. The number of different ways that audio material can be processed by Samplitude 10, in real time, and accessed at track, object and master level, is pretty impressive. As well as amplitude changes, there are three kinds of standard dynamics (channel dynamics plus advanced and multi‑band versions), a four‑band parametric EQ, a 'brilliance' enhancer and an FFT filter/spectral analysis tool. Delay and reverb options include the convolution‑based Room Simulator, while flexible time and pitch manipulation is possible thanks to the Timestretch and Elastic Audio algorithms, and there's a collection of Restoration Tools including de‑hiss, de‑crackle and de‑noise.

Of course, all DAWs now offer a wide range of plug‑ins, from basic EQ and dynamics to more unusual effects, but what raises Samplitude to the upper echelons is the very high quality of its 'standard' offerings, and its more specialist inclusions. The latter include the Analogue Modelling Suite and the Variverb algorithmic reverb, both considered good enough to be marketed as independent plug‑ins for non‑Samplitude users (reviewed by Sam Inglis in SOS August 2007: /sos/aug07/articles/magixplugins.htm). The AM Suite comprises more specialised compressors, and the version bundled with Samplitude Pro includes the fearsome‑looking, but superb‑sounding AM‑munition mastering limiter.

Samplitude also includes the very special Spectral Cleaning processor. I first tried this when I reviewed version 9 three years ago, and during the time since I have explored it more thoroughly and come to use it more and more, finding it incredibly useful, and only yielding to its specialist counterpart, CEDAR's Retouch (which is tied to its use in SADiE and costs three times the price of the entire Samplitude program), for the most exposed classical work.

New Plug‑ins

A worry is sometimes raised concerning the suitability of a particular processor (analogue or digital) for mastering. This is often phrased as asking whether or not X is 'mastering grade'. I think it's not really a good question, or if it is, it is badly phrased: as a number of my colleagues have pointed out, if you can use it to do effective mastering, then it is 'mastering grade'! A better question, perhaps, is about function, which focuses the question not on quality per se, but on implementation. For example, most mastering engineers would be happy to have their analogue EQ's gain ranges limited to, say, ±8dB, but would prefer to have the gain increments in switched 0.5dB steps. So a very high‑quality EQ that had pots instead of switches, or switches with 1dB steps, might nonetheless, on this basis, be considered less suitable for mastering. The same is true of 'mastering' compressors, which might ideally need smaller compression ratios and a greater range of time constants.

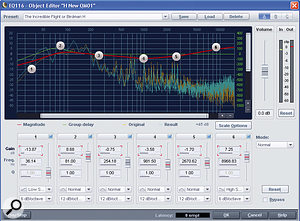

I'm making this point because, in terms of quality, the processors included in Samplitude 10 were certainly adequate for mastering: in fact, I know a number of mastering engineers whose only software processing alongside their outboard equipment is the EQ and multi‑band compressor in Samplitude or Sequoia. So the fact that Samplitude have included two new 'mastering' items in version 11 does not mean that they are necessarily better than and supersede those in earlier versions, but it does indicate that they are providing additional functionality that anyone who wants to use the program for mastering will find very useful. (In all there are actually three new processors, but the non‑mastering tool — the Vandal guitar and bass amp simulator — has followed the AM Suite and Variverb into the general market and as such was reviewed separately in August's SOS.)  The EQ116 mastering equaliser plots the original frequency response, in quite some detail, as an orange line; the applied curve is shown in red; and the resulting curve is shown, in detail equal to the original, as a blue line. So in the example here we can see that the (illustrative only!) bass boost at 81Hz is ameliorated, but not entirely eradicated by the slight dip at 254Hz and, in fact, only returns to the original and then starts to dip as the larger attenuation in band four comes into play.

The EQ116 mastering equaliser plots the original frequency response, in quite some detail, as an orange line; the applied curve is shown in red; and the resulting curve is shown, in detail equal to the original, as a blue line. So in the example here we can see that the (illustrative only!) bass boost at 81Hz is ameliorated, but not entirely eradicated by the slight dip at 254Hz and, in fact, only returns to the original and then starts to dip as the larger attenuation in band four comes into play.

EQ116 is a new six‑band EQ with a number of interesting features. For example, it has an advanced graphical display that shows both the EQ curve being dialled in at each point and the effective sum of all of the individual curves, and also provides a real‑time visual representation of the frequency content of the material to be processed and a representation of the effect of the processing. Of course, there are other EQs that also offer this kind of graphical information, such as Apulsoft's Apqualizr — but unlike Apqualizr, EQ116 can show all of this information at the same time, which is more clear and more elegant.

All of this can be very useful, although there is much discussion — it is an issue that comes up time and again on mastering Web boards — of the real value of visual representations in audio processing. A minority of mastering engineers seem to rely on them quite heavily, while the much larger majority would seem to think that they have a small, but closely circumscribed role to play, and another minority think they are the devil's spawn, a sign of rank amateurishness, and most likely a duff monitoring path. My own view is that they can be used very effectively by the beginning engineer who wants a tool that can aid in developing their ear‑training, by engineers who want to get a quick fix on a problem frequency and to both see and hear the effect of their solutions, and perhaps by a tired engineer at the end of the day who wants some visual confirmation that no monster frequencies have somehow sneaked in below his aural radar — or even just for simple interest in 'seeing' effects you would normally only hear. Cross‑modal perception (as it is called) can be a wonderful thing, and information is morally neutral: it all depends on what you do with it.

More interesting, from the point of view of mastering sonics, is the choice of three operational modes. The normal mode is basically the same as the existing four‑band parametric EQ, while the oversampling mode has a better amplitude frequency response and so has an audibly beneficial effect, especially on the higher frequencies (at the cost of higher CPU usage), and the linear‑phase mode does as it says, using filter processing that eliminates phase shifts (but, again, with a CPU penalty, and with a general down side regarding LP modes that we'll come to in a minute).

I really liked this EQ. Whether the graphics were really useful to me, I'm not sure: I'm old enough to still think it's pretty neat that you can see waveforms when editing, but when I'm mastering, I like clear space between me and my monitor speakers, so all the processors and computer monitors are actually behind me. I certainly found it interesting to be able occasionally to correlate what I could hear with the visual display. In terms of sound and functionality, this EQ is superb, and the different modes worked very well for me. In fact, I found that the different modes could even work in a complementary fashion. I like linear‑phase EQ for low‑end work such as high‑pass filtering, but like many others, I find that the pre‑ringing it can introduce is sometimes disturbingly audible in the higher frequency range. As the oversampling mode worked very well in this range, I tried cascading two instances of the EQ, set in different modes, so that I had both low‑end, linear‑phase and upper‑frequency oversampled EQ in the same object, and was delighted with the result. I have to report that on a couple of occasions when I tried this, my ageing Shuttle computer stuttered in real‑time processing, but I'm pretty sure this is computer‑specific and not a general consequence of the software.

The sMax11 plug‑in is offered as a very straightforward mastering limiter, with limited options compared, say, to Voxengo's Elephant. Also new in Samplitude 11 is a simple but effective mastering limiter. There are just three sliders for setting Gain In, Gain Out and Release, and four operating modes: Balanced, which is the most transparent and distortion free; Fast and Aggressive, with increasingly shorter attack times; and a Hard Clipper that simply snips the peaks, leaving the signal below them untouched. Considered just in itself, and especially if only called upon to do relatively light limiting, sMax11 works perfectly well. It took some time for me to get to grips with the combination of Mode and Release time, and I know that a number of people prefer full programme‑adaptive auto‑control here (as found in many limiters, such as Waves' L2 and the Flux limiter) but unless you need a much more invasive level of limiting, it is entirely adequate for a process that most of us wish didn't happen all that much anyway.

Also new in Samplitude 11 is a simple but effective mastering limiter. There are just three sliders for setting Gain In, Gain Out and Release, and four operating modes: Balanced, which is the most transparent and distortion free; Fast and Aggressive, with increasingly shorter attack times; and a Hard Clipper that simply snips the peaks, leaving the signal below them untouched. Considered just in itself, and especially if only called upon to do relatively light limiting, sMax11 works perfectly well. It took some time for me to get to grips with the combination of Mode and Release time, and I know that a number of people prefer full programme‑adaptive auto‑control here (as found in many limiters, such as Waves' L2 and the Flux limiter) but unless you need a much more invasive level of limiting, it is entirely adequate for a process that most of us wish didn't happen all that much anyway.

New Synths

Also 'new' are four percussion synth objects that are not based on input MIDI data but which can be programmed and edited to provide beats. These are not entirely new items, having been lifted from one of Magix's cheaper audio programs, and they are not really entirely at home in a program that presents itself as a serious professional package. Atmos, meanwhile, is an ambient sound creator with four basic modes: Ambient (jungles, water, wind), Chill‑Out (even more water: rain and oceans), Movie‑Score (yup, more water: thunderstorms) and Hip‑hop. At least Hip‑hop gives up on the water motif, though unfortunately it replaces it with abysmally typecast elements such as police sirens and parameter‑adjustable gunfights. Jamie, my nine‑year‑old daughter, played with all of these synth objects for a while, and pronounced them to be "fun”. Quite. Cream of the crop of new instruments are the Revolta2 virtual analogue synth (right) and the Vita sample player.

Cream of the crop of new instruments are the Revolta2 virtual analogue synth (right) and the Vita sample player.

Rather better as professional items are the VST software synths, especially the Vita sampler, which has some very nice acoustic sounds (piano, bass, woodwinds) for background arrangements, and even some that could be pressed into solo duty — not including the power chords! Revolta2 is a modelled analogue‑style synth, featuring "nine different effects and presets, designed by a famous designer”, and could be induced very easily to make gorgeous noises for which you would then want to find a home.

Other New Features

Before I finish, I need to just mention some of the other changes that are apparent, some of which arrived in incremental updates between 10 and 11. The most substantial new features would seem to be a whole set of what Magix themselves call "bread and butter” effects: a simple compressor, expander/gate, chorus/flanger, stereo delay, reverb and phaser. The point of these seems to be to provide basic functionality while conserving DSP power and screen real‑estate (they're quite small) but otherwise it eludes me: they're nothing remarkable and, like the percussion synths, are derived from Magix's consumer programs.

The new 'eFX' have been borrowed from one of Magix's more consumer‑oriented programs, and provide simple stock effects.

The new 'eFX' have been borrowed from one of Magix's more consumer‑oriented programs, and provide simple stock effects.

In point of fact, apart from EQ116, sMax11 and Vandal, and a super new metal dongle (cue sighs of relief from location recordists forever concerned that the fate of their careers was too much tied up with that of a flimsy plastic item), the whole upgrade is a bit thin compared to what was newly offered in 9 and 10. The Revolver Track option — see 'Revolver Tracks' box — is an interesting concept, and might work well for certain kinds of comping, or even composition, but I have to admit I didn't find much use for it during the review period. There is a new file export facility that supports the AAF/OMF standard, and a very useful FLAC export facility, which was actually part of the incremental improvements in version 10, but otherwise the changes are almost all literally cosmetic: there are a couple of new skins — one of them, Camo, very dark and nice — plus a new docking function for certain sub‑windows, and new colours and ways of assigning them. There are some new MIDI features, but the impression remains — and absolutely none the worse for it — that Samplitude's heart and soul is in its main audio facilities.

Conclusions

Does this relative paucity of new features really matter? Perhaps we're addressing two questions here: is Samplitude 11 a good buy, a high‑quality product that can achieve a lot for its relatively modest purchase price? And — a rather different question — is Samplitude 11 a worthwhile upgrade for current version 10 users?

My answer to the first is still an absolutely unqualified yes. There is no doubt that Samplitude is amazing quality and amazing value for the money. New converts who buy version 11 are going to be very happy people. But long‑time users (myself, for example: I've had Samplitude or Sequoia in my studio alongside other DAWs for almost a decade now, ever since version 7) might wonder if what they will find to use in 11 will, as yet, justify the money. I really like the EQ, and the limiter is no slouch, but software companies that now still charge hundreds of pounds for their plug‑ins are finding a precipitously declining market share, with truly excellent EQs and other plug‑in processors (yes: 'mastering grade') costing very much less. So I think I will leave that part as an open question. But to go back to the first one again: if you're in the market for a recording, mixing and — uh‑huh — mastering package, Samplitude is the one to beat.

Revolver Tracks

Suppose you've made an arrangement of a song that has three different instrumental interludes: say, a flute, a piano and a rip‑roaring guitar solo. Using the object–based approach in your mixes probably means that these will all be on the same track, with effects and gain adjusted in the object editor. Listening through to the first mix, you are struck with the idea that maybe the interludes would work better if they were in a different order. The only way to tell is to listen, by rearranging the track elements in various orders and then playing back the track. Revolver tracks are designed to make this process much, much easier: simply create a Revolver track for each different arrangement using the icon in the track menu (which, showing more of the macho macabre sense of humour that gave us AM‑munition and Vandal, Samplitude's designers have designed as a gun's bullet chamber) and then Alt+Page Up/Down through the alternatives. Simple, easy, and in some cases, extremely useful. Like the full version of Vandal, however, Revolver tracks are included only in the more upmarket Pro version of Samplitude 11.

Pros

- The very powerful and flexible object‑based approach to processing remains unique to this family of programs.

- Excellent suite of bundled plug‑ins, including the two new 'mastering' processors.

Cons

- Great value for the new user, but not so much for upgraders.

Summary

The new version of Samplitude develops the program's key strengths and adds appeal for mastering engineers, though it is light on killer features for those upgrading from version 10.

information

Unity Audio +44 (0)1440 785843.

Music Marketing +1 416 789 7100.