The Soundscape R•Ed/32 core unit (bottom) incorporates two bays for removable hard drives. Also shown are the iBox 8‑XLR/24 analogue I/O expansion rack unit (top), a selection of plug‑ins, and the ISA Host Interface card.

The Soundscape R•Ed/32 core unit (bottom) incorporates two bays for removable hard drives. Also shown are the iBox 8‑XLR/24 analogue I/O expansion rack unit (top), a selection of plug‑ins, and the ISA Host Interface card.

As PCs grow more powerful, native‑processing systems appear to offer very impressive features. Nevertheless, as Martin Walker explains, there is still a strong case for using dedicated audio hardware, as evidenced by Soundscape's powerful R*Ed system.

<!‑‑image‑>Why would anyone want to buy a dedicated box for hard disk recording, mixing and effects when a fast modern PC could do all this for you internally? Well, there are a number of reasons.

First of all, most experts accept that to get the best performance from a soundcard, especially if you want to benefit from the increased dynamic range of 24‑bit recording, it needs to have its converters and analogue circuitry outside the computer, to prevent them being bathed in radio‑frequency interference. This is even more important now that processors now reach speeads of 1GHz and we move into the realms of microwave interference, which is even harder to keep out.

A second consideration is that it is almost impossible to provide professional audio output levels using the cheap switched‑mode power supplies available inside computers. To produce a +22dBu signal, you need a peak‑to‑peak swing of nearly 28 Volts, which needs a dedicated power supply with significantly higher‑voltage rails than the ±12 Volt rails found in a PC.

<!‑‑image‑>High‑end systems such as Pro Tools and Soundscape, morever, also lighten the load on the host PC byrunning many (in Soundscape's case, virtually all) of the real‑time audio processing functions on dedicated DSP hardware. The Soundscape hardware also contains the hard drives used for audio recording. This arrangement provides significantly better performance than using the same drives inside a PC, because there is total control over the drive at all times — no sudden bursts of behind‑the‑scenes Microsoft housekeeping to interrupt the steady flow of audio, and no third‑party utilities running in the background. This enables their DAW systems to provide stable audio recording with a guaranteed number of tracks.

All that the PC does in a Soundscape system is to provide keyboard control and large‑screen editing facilities, and because all the hard work of recording, playback, mixing, and effects is already being done inside the rackmount unit, even a Pentium MMX processor is more than enough to act as a suitable control device. Of course, you may want to run a MIDI sequencer or soft synth/sampler alongside, in which case you will need a faster machine.

Soundscape's dependence on external hardware has the great advantage that if your PC should crash during recording or playback, the recording system will simply carry on regardless — even if you suffer a power cut, you can easily recover any in‑progress files afterwards. The Soundscape system also maintains a 26‑level history of changes to its hard drives, so that even if you change your mind about deleting a file, there's a good chance that you can still retrieve it.

The original Soundscape SSHDR1 system, launched in 1993, introduced their proprietary editing software, and their new systems since then (the SSHDR1+, reviewed in SOS November '97, and the Mixtreme, reviewed in April '99) have all been based around the latest versions of this program, allied to new or improved hardware. The long‑awaited R*Ed system continues this trend, combining the latest version 3 of the editing software with much more powerful hardware.

Overview

R•Ed is unusual in that it still uses an ISA‑format card, but it is much easier to install than ISA soundcards tend to be.

R•Ed is unusual in that it still uses an ISA‑format card, but it is much easier to install than ISA soundcards tend to be.

Three different types of R*Ed hardware unit are available. The largest unit, the R*Ed/32, which formed the basis of the review system, supports up to 32 tracks at 24‑bit/44.1kHz, or up to 16 tracks at 24‑bit/96kHz, subject to the type of hard drive you fit. Since the software supports up to four units, a theoretical maximum of 128 simultaneous tracks can be played back simultaneously, though as with most other DAWs, you can use many more virtual tracks (up to 256) than physical ones to provide flexibility. The unit provides a total of 26 digital inputs and 28 digital outputs via one AES‑EBU stereo input, two AES‑EBU stereo outputs, and three TDIF sockets each supporting eight inputs and outputs. The other units in the range are the R*Ed/24, which provides 24 tracks at 24‑bit/44.1kHz or 12 tracks at 24‑bit/96kHz, and has three TDIF sockets for up to 24 ins and 24 outs, and the R*Ed/16, which provides 16 tracks at 24‑bit/44.1kHz or eight tracks at 24‑bit/96kHz, and has a single TDIF connector along with the same AES‑EBU I/O as a full R*Ed system.

The R*Ed/32 supports two fixed drives fitted internally, and two in removable drive bays — these are ideal for quick changeovers between different projects — while its smaller siblings each have provision for one fixed and one removable hard drive. Any modern EIDE 7200rpm hard drive can be used, as long as it supports PIO Mode 4. Most do, but Soundscape publish a list of tested models at the end of their manuals, and keep an up‑to‑date list on their web site. Drives of up to 137Gb are supported.

All the hardware units communicate with your PC either through its parallel port, or via a supplied Host Interface card which supports one or two units. The host PC then runs the Soundscape software to provide control of recording, playback, and editing facilities.

Additional I/O

The iBox expansion units provide a variety of different I/O options, and connect to the main R•Ed unit via TDIF.

The iBox expansion units provide a variety of different I/O options, and connect to the main R•Ed unit via TDIF.

Should you want analogue I/O, or digital I/O in another format, you'll need to expand your R*Ed system with either an internal board or an additional converter box. There are a variety of options. The simplest is the basic Analogue board: this can be fitted internally, and its six XLR connectors replace a blanking plate on the back panel, providing two balanced inputs and four balanced outputs, all with 24‑bit/96kHz capability.

<!‑‑image‑>For those who need more connections to the outside world, Soundscape make available the iBox range of converters. There are currently five 20‑bit options: the 2‑Line, which provides basic stereo analogue I/O, the 8‑ADAT, which gives eight‑channel TDIF‑to‑ADAT conversion, the 8‑Line, which offers eight unbalanced analogue inputs and outputs, the 8‑XLR, which provides eight balanced analogue inputs and outputs plus word clock and Super clock, and the 8‑XLR Fibre, which replaces the word clock and Super clock I/O of the 8‑XLR by ST‑type connectors supporting up to 1km of optical cable. Three iBox models are currently available with 24‑bit capability: the 8‑XLR/24 provides eight balanced inputs and outputs, along with ADAT and word clock I/O, while the 8‑XLR/24 Fibre model once again replaces the word clock/Super clock by ST‑type optical connectors, and the 2‑Mic provides two balanced XLR mic/line inputs with 48V phantom power and a headphone output. Multiple two‑channel units can be daisy‑chained from a single TDIF port.

Physical Presence

Each R*Ed unit is housed in a rugged 2U rackmount case, which is quite deep at about 15 inches front‑to‑back. The only controls on the front panel are a rocker mains switch, two LED indicators for Power and SDISK activity, and two lockable drive bays for the removable hard disks, each with a green LED to show power and a red one indicating drive activity.

The back panel is more densely populated, though its contents will depend on what options you have installed. As standard there is an IEC mains socket, a panel‑mounted fuse and a fairly quiet cooling fan, three 25‑pin D‑Sub connectors for the TDIF I/O, a 68‑pin mini‑Centronics expansion port carrying a 512‑channel TDM audio buss (for the forthcoming Mixpander card — see the 'Expanding R*Ed' box), three XLR connectors for the AES‑EBU digital I/O, a pair of phono sockets for word/Super clock In and Out, and a trio of 5‑pin DIN sockets for MIDI In, Out, and Thru.

With the review system I also received an Analogue board, which gave me an excuse to open up the rackmount case. The build quality inside was extremely good, with a main motherboard containing the Motorola DSP chips and two plug‑in RAM boards, along with a completely shielded mains power supply and twin bays for the removable hard drives. One 10Gb removable unit was fitted in the review unit.

Fitting the Analogue board wasn't a trivial operation like installing a soundcard, requiring a total of 37 screws to be removed and fitted. However, it was straightforward, and after half an hour I had the new board in place complete with its own dedicated mains power supply and RF shield for optimum performance. The board uses AKM AK5393 A‑D converters (the same as the Echo Mona and very similar to the AK5383 of the M Audio Delta 1010), but the D‑A converters were Analog Devices AD1855s, which are new to me.

Installation And Setup

Plug‑in effects available include Aphex's Aural Exciter and Big Bottom Pro.

Plug‑in effects available include Aphex's Aural Exciter and Big Bottom Pro.

There are two ways of installing R*Ed — via the supplied ISA Host Interface card or an optional parallel‑port interface cable. Both provide exactly the same performance, but Soundscape told me that most users find the ISA card easier to install and set up, since the default settings nearly always work first time, and you don't need to delve into the BIOS to check that your parallel port is set to EPP status as you do with the parallel‑port cable. However, the cable would be more suitable for those whose PCs either don't have a spare ISA expansion slot, or for laptop owners.

ISA soundcards can be a pain to install, and often take up multiple interrupts and DMAs, but this card is much simpler, and the default 250h (hexadecimal) settings didn't conflict with anything in my PC. Even so, it's a long time since I had to use the 'Add New Hardware' applet of Control Panel to manually install a hardware device. However, this only has to be done once, and the 1.5‑metre‑long umbilical cable has an extra connector for a second R*Ed unit, so this one ISA card caters for up to 64 tracks of 24‑bit audio.

Using R*Ed

<!‑‑image‑>I then installed the Soundscape R*Ed Editor version 3.0.1 from the CD‑ROM, and after typing in the 12‑digit password (see the 'Soft Security' box) was able to start making music. The editor looks almost identical to that used by the SSHDR1+ and Mixtreme systems, and indeed a free update is available to existing users of both the SSHDR1+ and R*Ed. However, this new version includes automation (see box). It's compatible with Windows 95, 98, NT4, and 2000. (For those who want built‑in MIDI support or who are already familiar with Logic, Emagic have now integrated R*Ed support into Logic Audio Platinum; since all audio tracks are played from dedicated hardware, excellent MIDI timing is claimed as a result.)

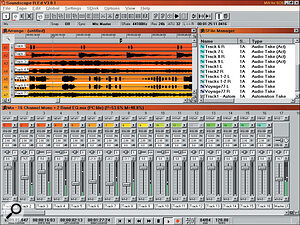

<!‑‑image‑>The main R*Ed editor window is relatively uncluttered, with one of nine customisable toolbars across the top, an optional status bar beneath, and a comprehensive tape transport bar across the bottom. Various other windows can appear inside the main one, and the editor initially opens with default Arrange and SFile Manager windows. The Arrange window holds a number of audio and automation tracks, and can contain a total of up to 8192 individual audio and automation parts. Across the top it displays a timing ruler, and beneath this a marker display capable of holding up to 999 named markers per arrangement. There are track indicators down the left‑hand side, and various vertical and horizontal zoom options. Above a certain vertical zoom level, audio waveforms and automation data can be displayed inside the parts.

An SFile is simply any file stored on the Soundscape hard drives, and the SFile Manager operates very much like Windows Explorer, letting you load, save, and organise the contents of all drives installed in your R*Ed rack. It supports long file names, project folders, optional file comments, and has utilities to format and defragment your drives. You can also transfer files to and from your PC's hard drives; I moved a 10‑minute song in WAV format over to try out, and it took a couple of minutes. Various other windows are available, including a Marker Directory, Big Current Time, and Mix Window (covered in the next section).

<!‑‑image‑>Recording is simply a matter of right‑clicking over the left‑hand record track column of the Arrange window, and choosing either a mono or stereo audio track or an automation track (more on these later). Once created, you can 'arm' tracks by clicking on their record status indicators, and then start recording using the tape transport record button. You can also punch In and Out automatically using the left and right locators, set up pre‑roll and post‑roll, and loop record with up to nine stacked takes. Setting the tempo and time‑signature readouts on the transport bar determines the time axis display and the snap grid, and MIDI Clock and Song Position Pointer information based on these settings is also generated if you want to synchronise a MIDI sequencer (resolution is 192 ticks per beat).

The range of tools and options on offer is comprehensive. To use them, you can either click on the menu option itself, or its tool icon (if currently shown on one of your customisable toolbars), and you can also define up to four tools to use directly with the left and right mouse buttons, with or without the Alt key — the current selections are displayed under the tools in question.

You can Move and Copy parts in a variety of ways, Trim their start or end positions, Slip takes within parts, Cut and Glue them back together, Repeat them, add fades in or out using a variety of curves, adjust overall volume levels, and audition them with variable‑speed Scrub tools. Audio processes also have dedicated tools, including Normalise, Noise Gate, Reverse, Invert, DC Removal, and more exotic options such as Time Stretch/Compress, Timelock, Pitch Shift, Sample Rate Convert, and Mixdown (which allows up to 30 active tracks to be digitally mixed together to form a new stereo track). If you have bought suitable software, the Xpro tool lets you apply off‑line processes such as Synchro Arts' Vocalign or CEDAR'S Declick and Dehiss. A 10‑level Undo function is provided, along with extensive keyboard shortcuts.

Mixing & Effects

I've always liked Soundscape's virtual mixer design, largely for its versatility. You can create any configuration of mono or stereo input and output channels, with added EQ and real‑time effects, as long as you don't exceed the DSP power and internal RAM available, and then load and save these designs at will, depending on whether you are currently recording, mixing, mastering, and on what I/O you have connected.

The mixer can be freely switched between Full and Small views: in Full view every control is visible, but only 11 channels can be displayed side‑by‑side across a typical 1024 x 768 screen, whereas Small view narrows the horizontal sliders and removes solo and group buttons to fit 16 input and one output channels across a similarly sized screen.

<!‑‑image‑>Each channel has a basic signal path comprising (from top to bottom) input assignment, a user‑definable section containing any combination of two‑band parametric EQ, Fader, Sample Delay Line, Peak Meter, Send Pre/Post, and any other installed effects, followed by a horizontal slider for Pan/Balance, a Main fader and pre‑fader PPM meter, Mute and Solo buttons, and finally output assignment. Two further buttons labelled FG and SG let you set up Fader Groups, allowing you to move every fader in the group together using the right mouse button instead of the left, and Solo Groups, which work similarly for grouped solo buttons.

It's worth remembering that you can add any elements you like to a mixer channel — if you want a four‑band EQ, for instance, you can simply cascade another two‑band one, or for a more complex facility you could create a set of parallel, band‑limited input channels, adjusting their faders like those of a graphic EQ. Although EQ parameters can be adjusted by left/right clicking with the mouse, it is easier to double‑click on the appropriate area of the mixer channel to launch the dedicated EQ window with its slider controls and graphic display of frequency response. This approach is also used for plug‑in effects, which allows third‑party developers to use whatever graphic interface they choose.

<!‑‑image‑>You can add further channels and functions whenever you like, subject to available memory and processing power; these are displayed across the title bar. To give you an idea of available RAM and DSP power, the recommended starting point is a setup called Mix3. This has eight stereo input channels, each with input routing box, associated horizontal peak‑reading meter and two‑band parametric EQ. Each of these channels also has a Track Insert (with its own level fader) for monitoring unprocessed hard disk playback during tracking. A single stereo output channel completes the setup. In total these elements consume 53.8 percent of the processing power and 55.2 percent of the available RAM. Dedicated tools are available for mixer design, including Create for new elements or complete channels, Loudspeaker for routing, and Mute, which lets you deactivate currently unused elements or channels and returns their DSP and RAM to the pool for other uses.

Twenty‑seven mixer designs are included, ranging from simple eight‑stereo‑in setups through to 32‑channel designs complete with a variety of pre‑configured effects, though the effect columns only appear if you have bought and authorised the appropriate software.

The range of third‑party plug‑ins available to Soundscape owners has grown over the years, though there are still nothing like as many as are available for Digidesign Pro Tools TDM systems. The current range includes Aphex's Aural Exciter and Big Bottom Pro (see screenshot), Apogee's UV22 Mastertools, Arboretum's Hyperprism pack, CEDAR's audio restoration tools, a Dolby Surround Encoder/Decoder (see screenshot), Sonic Timeworks' CompressorX, Synchro Arts' Vocalign, TC Works' Dynamizer and Reverb, and Wave Mechanics' Reverb. I've already looked at several of the Soundscape effects in my Mixtreme review (see SOS April '99), and it's worth remembering that since the Soundscape system provides dedicated DSP power, algorithms can be more luxurious than those running as native DirectX or VST‑compatible versions. This was particularly noticeable with the TC Reverb, which sounded significantly smoother and denser in its Soundscape incarnation.

Final Thoughts

The new automation features let you capture the moves from most controls on dedicated tracks, one for each mixer channel. When recording, the new icon at the bottom right of the mixer activates automation.

The new automation features let you capture the moves from most controls on dedicated tracks, one for each mixer channel. When recording, the new icon at the bottom right of the mixer activates automation.

Once I got to grips with the editor interface, I didn't have a single operational problem while using R*Ed. Its Analogue board provided excellent audio quality, and recording, playback, mixing and adding effects were all straightforward. I did come across a couple of graphic quirks, with selection choices occasionally disappearing off the bottom of the screen and colour strobing of the track displays when moving other windows over the top, but these were both minor and inconsequential. As with previous Soundscape products, I still miss context‑sensitive help for the tools, but regular users won't need this, and the printed manual is very well written.

Obviously, it's impossible to assess the long‑term stability and product support after spending only a few weeks with a review system, but Soundscape setups do have an excellent reputation. Plenty of Soundscape systems originally bought in 1993 are still in daily use seven years later, and in that time the software has also undergone several major revisions, and a series of free updates have been available to all registered users. Several of my friends use Soundscape systems almost exclusively for their work, and are extremely satisfied with them, having nothing but praise for their audio quality and reliability. R*Ed may seem like a substantial investment, but you can expect it still to be going strong in years to come.

Full Mix Automation Now Included

The latest version 3 software now supports automation, and automation tracks are treated exactly like standard audio ones — you create an Automation track for any of the 128 virtual mixer tracks, arm it, make sure the Automation Enable button at the bottom right of the mixer is active (see screenshot), and then click on Record and start moving controls. You can find out which controls for a particular track are automatable by using the Info Tool, and any number of those controls can be recorded into a single automation track.

There are three modes for automation recording. Normal Record only records knob changes, while Touch Record keeps existing automation data during subsequent passes until you update a control — new data is then recorded until you release it, at which point it again follows the previous data. Touch Record Till Stop is similar, except that once you update a control it carries on recording new data until the end of the recording. A Snapshot button on the mixer lets you capture the current positions of all automatable controls in currently armed tracks, and is ideal for setting initial values at the beginning of an arrangement.

Once automation has been recorded, you can use the Automation Curve Select tool to choose which single parameter to view in each automation part — the part name displays the current parameter. Automation data can be automatically smoothed and thinned, or you can use the Automation Thinning tool, and an Automation Event Editing tool lets you move or delete existing data, or draw in new points.

Soft Security

Soundscape employ what I consider to be one of the best software protection methods currently in use. Each R*Ed, Soundscape SSHDR1, and Mixtreme card has a unique serial number burned into its hardware, and each item of software that you install also requires a correspondingly unique 12‑digit password to unlock it for use. The beauty of this approach is that Soundscape can freely circulate all their software, and an added bonus is that other developers have far more confidence that their products won't be pirated. This has resulted in the development of a number of high‑quality third‑party plug‑ins, although sadly it hasn't resulted in a corresponding drop in prices.

My installation CD‑ROM not only contained the Soundscape R*Ed Editor version 3.0.1, but also the full versions of the Aphex Aural Exciter III and Big Bottom Pro, CEDAR Declick and Dehiss, Dolby Surround, TC Dynamizer and Reverb, and their own Audio Toolbox and CD Writer. If you want to use any of these, or when you buy other Soundscape‑compatible products from third‑party developers, you simply contact Soundscape or one of their distributors, and your unique password will normally arrive within 24 hours.

Expanding R*Ed

One extremely flexible way to expand a R*Ed system is to install a Soundscape Mixtreme soundcard in your PC, and connect its twin TDIF connectors to two corresponding connectors on the R*Ed rack unit. The Mixtreme's 16 channels and onboard DSP power are instantly added to that already available in the main rack unit, so that you can add lots more effects to your R*Ed tracks: effectively, you're using the Mixtreme as an outboard effects unit. The forthcoming Mixpander will have 64 channels, and connects to R*Ed using its Expansion buss.

The Mixtreme and Mixpander multi‑client PC drivers also let you run different soft synths and soft samplers with very low latency (down to 1.5mS) on each stereo output pair, and this has made Mixtreme very popular among users of products like Nemesys' Gigasampler, NI's Reaktor, and Seer Systems' Reality. These can all be run simultaneously, even with different driver types and sample rates, and each treated with different Soundscape EQ and effects. Once you attach this combination to a R*Ed you can also plumb the channels back into your rack unit and record the final output as audio tracks.

Given the routing flexibility of Soundscape's mixers, you could also add DirectX or VST‑compatible effects to R*Ed tracks with a suitable application, although this might be rather complex to set up initially. For those who occasionally want to add a special effect only available from such PC‑based plug‑ins, you could add these off‑line even with a standard R*Ed system, by using its Import and Export functions to transfer SFiles between the dedicated hard drives and your PC hard drive, where effects can be applied.

Prices

Soundscape Systems

- Soundscape R*Ed/32 including Host Interface card, cable, and version 3 software £4694.13.

- Soundscape R*Ed/24 £2995.

- Soundscape R*Ed/16 £2995.

- R*Ed Analogue board £587.50.

iBox Interfaces

- 8‑XLR £999.

- 8‑XLR/24 £1495.

- 8‑XLR Fibre £1495.

- 8‑XLR/24 Fibre forthcoming: price tbc.

- 8‑ADAT £150.

- 8‑Line £350.

- 2‑Line £150.

- 2‑Mic £430.

Prices include VAT.

Control And Integration

R*Ed provides compatibility with a wide range of moving‑fader hardware controllers for the ultimate in remote control using its MIDI In or Out connections. Soundscape sent me the impressive JL Cooper MCS3800 to try out, which offers eight motorised long‑throw faders, a huge jog/shuttle wheel, and a comprehensive transport section. Soundscape provide Console Manager software to connect multiple controller devices to their hardware; this has a flexible plug‑in‑style architecture to make it easy to add support for future controller types.

Integrating R*Ed into a studio is also made easy by the number of clock options. Master clock can be chosen from Internal, AES‑EBU (S/PDIF), from any of the TDIF connectors, or from word or Super clock. The R*Ed Sync option provides additional VITC and LTC Master/Slave facilities, along with RS422 Master/Slave (Sony 9‑pin protocol), and Video Sync (black burst).

The editor software also includes an AVI Player for Microsoft's Video for Windows, while for more demanding applications you can use one of a variety of dedicated video‑capture cards such as the Miro DC30 for full‑screen, full‑motion video on a separate monitor screen. This should prove ideal for things like dialogue replacement and audio dubbing for film and TV post‑production.

Pros

- Excellent audio quality and good reputation for reliability.

- Up to four units can be stacked for 128 tracks of 24‑bit/44.1kHz audio.

- Built‑in DSP for mixing and effects and expandability using Mixtreme or Mixpander PC cards.

- Can work with a laptop PC.

Cons

- It's fairly easy to run out of DSP power if you need lots of simultaneous EQ and effects.

- Professional performance comes with professional price tags.

- Would still benefit from more third‑party plug‑in support.

Summary

R*Ed is a versatile and expandable 24‑bit recording system with excellent audio quality, a reasonable selection of third‑party plug‑ins, and a reputation for reliability that will endear it to many professional musicians.