Yamaha's former sampling flagship, the A3000, represented a novel but very powerful approach to sampler design. The new A4000 and A5000, as Derek Johnson & Debbie Poyser report, maintain the distinctive design ethos, but should provide even stronger competition to the established names.

<!‑‑image‑>If you'd been looking for a new studio rackmount sampler a few years ago, it wouldn't have taken long to list the options: UK industry‑favourite Akai or respected US institution Emu. Like Coke and Pepsi, MacOS and Windows, HP and Daddies, these two giants slugged it out with little serious competition to distract them. Worthy machines in Roland's S700‑series gave samplists pause for thought, but then Roland shifted their focus towards 'groove' samplers, leaving the big two alone in the ring once more.

Until mid‑'97, when Yamaha threw down a glove with the launch of the A3000, their first studio sampler for almost 10 years. Labelled 'Professional Sampler', the A3000 combined plenty of features and power with an affordable price. It wasn't universally liked in all aspects — the SOS review (July 1997) found its operating system 'arcane', for example — but there was no denying that it provided unprecendented value for money. The A3000 and the 1998 v2 upgrade must have made their mark, because Yamaha are decidedly not moving away from professional sampling: two new A‑series machines are on the loose, still looking good on the price and spec front, and still providing that bit more choice in the sampler market.

Inside & Out

The A5000's large display is far superior to that of its predecessor, the A3000, though it doesn't quite match that of Akai's S5000.

The A5000's large display is far superior to that of its predecessor, the A3000, though it doesn't quite match that of Akai's S5000.

<!‑‑image‑>The new A‑Team consists of the A4000 (£999), and the flagship A5000 (£1499) under review here. (We've outlined how the 4000 differs in the 'A4000 Differences' box on p152.) Even a brief list of the 5000's features runs to a lot of words: mono/stereo 16‑bit sampling, 126‑voice polyphony, 32‑part multitimbrality, 4Mb RAM as standard (expandable to 128Mb), four analogue outputs (expandable to 10 with the AIEB1 board that also features S/PDIF digital I/O), synthesis facilities, and comprehensive effects, looping, editing and DSP tools. There's space inside for a SCSI or IDE hard drive (plus SCSI connection for an external drive), a floppy drive which can be replaced with a Zip removable, a CD‑burning facility, simple Standard MIDI File playback sequencer, real‑time MIDI controller knobs, editing software, and a set of free sample CDs. It also reads Akai S1000/3000, Emu EIIIx, Roland S760, WAV and AIFF samples, plus some Yamaha synth voice/wave data, and can save in WAV or AIFF as well as native format. Nice...

The well‑endowed A5000 offers some significant improvements over the 3000 — multitimbrality and polyphony are doubled, as is the quotient of effects processors — while retaining the same basic look and operating system, with certain enhancements. Physically it's differentiated not only by its gun‑metal livery (which contrasts with the 3000's blue) but also by its 13 x 3cm backlit graphic LCD which, though not quite as vast and eye‑poppingly gorgeous as those on the latest Akai samplers, is giant compared to the 3000's.

The display probably makes the biggest impact on the usability of the A5000 over the 3000, providing space for menus, icons, and waveform displays. Like the 3000's LCD, the 5000's works in tandem with five knobs beneath it, which line up with parameters in the display, selecting them or changing their values. The knobs can also be pushed to confirm certain operations. Choosing function‑specific windows is done with a familiar Yamaha front‑panel matrix: five labelled operating modes (Record, Edit, Play, Disk, Utility) are arranged along one axis, each with accompanying status LED, while the other axis offers six switches to select each mode's six 'Functions', again with LEDs.

Also on the front panel are two analogue inputs, a headphone socket, Master and Record Volume knobs, an LCD contrast control, three buttons that access some miscellaneous functions not covered by the five Modes, a power switch, and the floppy drive. The Big Book Of Reviewer Dos And Don'ts (sadly, this doesn't exist) says we now have to talk about the rear panel. This contains four analogue outputs (L, R plus two assignable), a SCSI socket, two sets of MIDI I/O, an outlet for the reasonably quiet fan, and a mysterious blanking panel. Well, it won't be that mysterious to those who read last month's Apple Notes, in which Paul Wiffen explained that the blank spaces turning up on Yamaha gear lately are related to the new mLAN connection protocol. The one on the A5000 can, alternatively, accommodate the AIEB1 board mentioned earlier.

Going Deeper

Before we look more closely at what the A5000 can do, we should examine its internal sound hierarchy. Unfortunately, the manual deals with the issue of sample organisation very badly, so we'll try to fill that gap here.

Many samplers use a system similar to modern sample‑based synths. You start with a sample, one or more samples are arranged into a multisample, and then one or more multisamples are assigned to a program or patch, where the multisample(s) are provided with synthesis facilities and perhaps layered or split according to key or velocity ranges.

You can pretty well disregard that idea when it comes to the A5000 (and the A3000 before it). All the required options for multisampling, synthesis, and key/velocity splitting are available, but they're applied to the centre of the A5000 universe, the individual sample, which is quite autonomous. Up to 960 samples can be on board, and each can have its own central pitch, key range, synthesis parameter settings and effects routing. For easier management, related samples, such as multisampled piano notes or drum kit voices, can be collected together in what's called a Sample Bank. So far, so straightforward.

Now things get a little more complicated, with two modes available for putting samples into a multitimbral form where they can be played over MIDI. In Single mode, all you do is assign samples and/or Sample Banks to an empty Program slot, of which there are 128. That's it. The Program basically becomes a multitimbral setup, as all the samples/Banks in it have their own MIDI channels and so on. The A5000 differs from the 3000 in also offering a dedicated Multitimbral mode, where the method is slightly different. Each sample and Sample Bank that you want in the multitimbral setup is first assigned to a Program slot, and the resulting Programs are assigned to Multi parts, each with its own MIDI channel. The latter resembles the way most hi‑tech musicians are used to operating.

It's fairly easy when you've got your head around what Yamaha have done, but one does wonder why there are two ways of doing basically the same thing — playing samples multitimbrally. Perhaps the first approach is simpler for novices. It's quick and does away with the whole (perhaps unnecessary) idea of having to make a multitimbral setup, because the Program is the multitimbral setup. The second approach has the advantage of familiarity for some people, and makes retrieving Programs for use in other songs more straightforward.

The fact that each sample can have independent filter, EG and LFO settings, plus a routing to one of the effects processors, is a very powerful aspect of the A5000. However, you'll often want to apply the same settings to a group of samples (a multisampled piano, for example). Fortunately, you can: almost all sample parameters are also available to a Sample Bank. Changes made to a Bank are applied as offsets to the settings of its constituent samples, the individual settings of which remain intact. If you edit one Sample Bank in which these samples are used, the same edits won't carry over to other Banks which use those samples, so the same samples can be used freely and repeatedly: very RAM efficient. I f you should want edits made at Sample Bank level to stay with the individual samples, you use the Freeze command. In addition, at Program level there's an Easy Edit facility providing further offset editing of a smaller group of parameters. Easy Edit offsets can also be 'frozen' to samples.

Start Sampling

Tiny Wave Editor has just one screen, and this is it. Here an entire sample is shown in the top display, plus a zoomed portion in the large working area. All the sample's 'personal' details are listed on the virtual file card to the left. You can do any editing here that you'd be able to do in the A4000/5000, plus more.

Tiny Wave Editor has just one screen, and this is it. Here an entire sample is shown in the top display, plus a zoomed portion in the large working area. All the sample's 'personal' details are listed on the virtual file card to the left. You can do any editing here that you'd be able to do in the A4000/5000, plus more.

The business of sampling is undertaken in Record Mode, where six pages cover aspects of preparing to record, and recording a sample.

First stop is the Setup page, where you decide which input(s) to record from. Stereo sources can be automatically summed to mono, to save memory, and you can also choose to resample the A5000's mixed output, complete with effects. A sample rate is set here, too — 44.1, 22.05, 11.025 or 5.5125kHz via the analogue inputs, plus 'lo‑fi' options for the lower three. The digital input, if fitted, accepts 32, 44.1 and 48kHz rates, but you can record digital audio at half, a quarter or an eighth of its actual frequency, also giving a 'lo‑fi' effect. Stereo or mono sampling can be defined, and the sample can be given a destination key, key range, and pre‑trigger amount. The A5000 constantly samples its input, and setting a pre‑trigger amount makes it retain the fragment of audio before sampling is initiated, so you never miss the start of wanted audio.

If automatic triggering is your bag, you'll visit the Trigger page next, to set thresholds upon which automatic recording will commence and stop. The Effects page only needs a visit if you want to sample through the A5000's effects — a welcome facility which can save having to tie up effects later. Next up is the Monitor page, to set a click to play against if you're sampling your own playing. (A sample recorded like this has the click tempo stored with it, making life easier in the Trim/Loop page, later — how thoughtful.) Sampling is actually initiated in the Record page, where you can also Optimise (defragment) sample RAM.

The sixth Record mode page is 'External Control', which usefully allows the transport of a SCSI CD‑ROM drive to be controlled from the A5000, for sampling from an audio CD. Unfortunately the audio doesn't come in digitally via SCSI, but via the CD‑ROM drive's analogue outputs.

It might seem that Record mode sends you through lots of pages just to record a sample, but most people will only have to set up working preferences occasionally, because the A5000 remembers your settings. So if, say, you'll generally want to record mono samples at 44.1kHz, from the left analogue input, with manual triggering, not going through effects, you set these things up once and they're stored. Making a sample thereafter could simply entail going to the Record page, setting a level (there's an input meter on the page), and hitting 'Go'. If needs change, you tweak the settings. Especially useful during tweaking is the fact that the A5000 can be set to remember where you last were in each page and take you right there, instead of defaulting to the top of that page — though it can do that too.

So sampling with the A5000 is pretty straightforward, and Yamaha have tried to make it even more convenient with a couple of refinements. First, samples can be automatically normalised after recording, ensuring the best possible signal level without clipping. Sampling takes slightly longer with this feature enabled, but that's a small price to pay for a very audible improvement in level. (Samples can be recorded straight and normalised later, if preferred.)

Then there's a very useful consecutive sampling facility, which enables the capture of multiple samples on the fly without the need to start and stop recording each time. The process is even automated when you choose automatic triggering of sampling — brilliant for pain‑free recording of multiple sounds off audio sample CD. Samples can also be automatically collected into a Sample Bank (or Program) and mapped to adjacent keys, whether recorded via consecutive sampling or not. If you don't want them so mapped, re‑mapping afterwards is easy.

Once in memory, a sample can be auditioned with the Audition button, which can even cycle through every sample in a Sample Bank. However, if the sample hasn't been auto‑mapped to a Program, it will have to be assigned to a Program, in Play mode, before it can be played via MIDI.

Editor's Choice

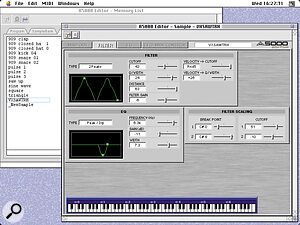

The Filter page in A5000 Editor's Sample window. Here it's possible to edit the chosen sample's filter and EQ parameters; other pages in the Sample window let you edit its keygroup and output routing, envelope generators, LFO and MIDI controller assignment. A similar editor for the A4000 is included on the free CD‑ROM.

The Filter page in A5000 Editor's Sample window. Here it's possible to edit the chosen sample's filter and EQ parameters; other pages in the Sample window let you edit its keygroup and output routing, envelope generators, LFO and MIDI controller assignment. A similar editor for the A4000 is included on the free CD‑ROM.

Edit mode is the place to be for anything from a simple trim and loop to a radical 'remix' of a sample. All edits can be undone (to one level), but only if the sample in question has been saved to disk. Moral: save often!

Various mundane but important sample‑specific parameters are set in Edit mode. These include a sample's desired key and velocity ranges (easily set using an attached MIDI keyboard), crossfades between key and velocity zones to smooth sample transitions, level and pan position, sample velocity response, and routing to the outputs or onboard effects. (Since many sample‑level parameters can be overridden at Sample Bank or Program level it's quite acceptable to choose nominal values to start with.) You can even apply Expand parameters to a sound: these enhance the image of a stereo sample or 'stereo‑ise' a mono sample. Extreme values create a 'chorusy' effect.

Trimming and looping operations are also available here. Only the top half of a sample's waveform is shown in the display, which initially seems odd but doesn't compromise your ability to work with the sample. First, you may want to trim unwanted material at the start and end of a sound. The zoomable waveform display (which goes down to single‑sample level) has cursors at the sample's start and end points, and these points are also shown numerically. Two knobs below the display move the cursors, in increments of one, 10, 100, 1000 or 10,000 samples. For speed, start and end points can be pu nched in on‑the‑fly as a sample plays. Once its length is adjusted to your satisfaction, the Extract function deletes unwanted audio.

Looping uses similar tools to trimming, including another pair of cursors for loop start and end. The A5000 offers just one loop per sample (though there's the choice of letting audio after the loop point play out once a key is released, or not, which can help to add interest during a sample's release). Looping is a tedious job with any sampler but the A5000 has ways of making it more bearable, and good loops can be easily achieved on both instrument‑note samples and rhythmic material. For a start, you can hear loop changes in real time while holding down a note. The A5000 will also let you scroll through the sample from zero crossing to zero crossing, until you find the one that yields the smoothest loop — great for avoiding clicks.

Sometimes, however hard you try, there's just no good loop point in a sample. This is where crossfade looping, which helps disguise awkward joins, comes in handy. The A5000 offers a choice of three crossfade curves, and you can set a percentage of the loop to be crossfaded, plus whether the crossfade area will derive from the sustain or release portion of the sample.

There's still more about the Trim/Loop page that's worth mentioning, including a 'wave start address velocity sensitivity' parameter. Don't let the name put you off: this parameter simply causes a waveform to play back from a point inside itself rather than its official start point. The playback point (over which one has limited control) changes according to velocity, yielding some very neat effects. Last in this area is the Loop Tempo control, which lets you assign a tempo to a rhythmic loop or tell the A5000 to determine tempo for you. The latter option works nicely as long as the sample is some multiple of four beats long — ideal for matching breakbeats and loops. It's doubly useful since looping a sample can be done in terms of beats, and once the A5000 has worked out a sample's tempo, it also knows how many beats it has. The timestretching function, too, is easier to use if you work with a known tempo.

Bend It, Shape It

The A5000's synthesis facilities comprise filters, envelope generators and low‑frequency oscillators. The multi‑mode filter features three kinds of low‑pass, two high‑pass, one each of band‑pass and band‑eliminate, two peak filters, and a variety of dual filters — each filter type has adjustable cutoff frequency and resonance, plus a cutoff distance control for dual types. Both cutoff frequency and resonance can be modulated by velocity, and a scaling function alters filter response according to where a sample is played on the keyboard. There's even a well‑specified single‑band EQ on the Filter page (in addition to a 4‑ba nd 'Total' EQ dedicated to a whole stereo mix and found elsewhere). In all, the filter is very comprehensive, and the possibilities are staggering given that every sample could have its own filter settings. Soundwise, it's capable of being absolutely evil, with a huge amount of bottom end, and the potential to be very cutting. Watch out for those speakers...

There are three EGs on board, one each for amplitude (following the attack‑decay‑sustain‑release model of classic synths, with one or two small enhancements), filter and pitch. Each sample also has its own LFO, with choice of waveform (sawtooth, triangle, square, sample & hold), speed (though the S&speed is, rather confusingly, altered at Program level), delay, and depth amounts for amplitude, filter cutoff and pitch modulation. At this point, one greedily wishes there were three LFOs per sample, to modulate the three destinations independently!

The synthesis section does everything you'd reasonably want — the 5000 even has seven basic synth waveforms so you can create sounds from scratch without sampling — and Yamaha have sensibly made it comprehensible rather than esoteric. Yet there's enormous power available just by virtue of the fact that every sample can have its own settings. Since the 5000 holds up to 960 samples, that's almost like having 960 little synths. Parameters can be easily copied from one sample to another, too, so although, for example, there isn't a library of preset envelope shapes, you can nick a suitable envelope from another sample. The one niggle in the synthesis area is that the A5000 has inherited the A3000's counter‑intuitive value range of 127‑0 for envelope stages — for example, the fastest attack is 127 and the slowest 0.

Jam Today

So much for bread‑and‑butter sample manipulation and synthesis. Now for some jam...

<!‑‑image‑>Loop Remix, featured on CS6x control synth and the A3000 v2, is a great process that divides a looped sample and randomly re‑orders it, in terms of sound quality, pitch and playback direction. It's non‑destructive and can be performed repeatedly until you like the result and save it. One A5000 innovation is that more user interaction with Loop Remix is possible, via four tweakable parameters, though the outcome remains fairly unpredictable! Probably the most useful results are achieved with rhythmic material, but it also has potential for textures, sound effects, and 'weirdening' speech samples. Remixing a melodic loop could even produce a new melody. Note that Remixing requires sufficient RAM for the original and the Remixed version to co‑exist.

The other major sample‑mangling tool is Loop Divide. This chops a sample into up to 32 equal chunks then puts them in a Sample Bank, mapped to consecutive keys. Ideal for dividing drum or other rhythmic samples into component parts, it's also effective for chopping other material into bits. For example, a two‑bar sample of any musical material can be divided into 16 chunks roughly an eighth‑note long, and said material reorganised just by triggering the new samples in a different order. An option to set custom Loop Divide points, using markers, would be nice — maybe in an upgrade?

Further tools include DSP processes such as time‑stretching, pitch change, sample reverse and fade in/out. All work as expected, with time‑stretch being particularly good. Quite extreme stretches produce usable results, and you can specify a weighting towards better sound quality or more rhythmic integrity. Oddly, there doesn't seem to be a way of reducing a sample's rate by 'downsampling'.

Yet another flavour of jam is offered by the Program LFO (which is separate from the sample‑specific LFOs). This MIDI‑sync'able device can modulate a wide variety of destinations, at Program or sample level, and can create some extraordinary effects with its programmable waveform option. Routing the Program LFO to filter cutoff, for example, produces automated super‑TB303 madness, while sending it to a sample's pitch results in instant pseudo‑algorithmic delirium that's anything but well‑tempered.

Most Effective

Another A5000 high point is effects. A generous total of six processors is provided, each of which can be assigned one of 96 effects covering pretty much every treatment you could reasonably ask for — plus various unreasonable ones! The processors are organised into two banks of three, but it's easy to create effect chains using all six.

Various flavours of delay, reverb, chorus and flange are augmented by distortion, overdrive and amp simulation, a turntable effect, digital scratch, and the eccentric jump and beat‑change effects, which chop up or modify the input signal in real time. Radio simulation, rotary speaker effects, compressors, enhancers and noise gates are all offered, and a significant number of effects comprise dual or triple chains — compressor/ distortion/delay, for example. Nine treatments, including some delays and flanges, can be sync'ed to MIDI clock. All effects are fully editable, with a maximum 20 parameters each, though a 'favourite' option lets you choose four preferred parameters to pop up on screen.

The effects would certainly be one of the creative samplist's reasons for buying this machine; as well as being diverse, they're generally of good quality. Distortion and overdrive effects are occasionally harsh, but modulation treatments are warm and pleasing. Reverbs are slightly grainy and would be too unsophisticated for some applications, but they have a character that's desirable for others. The delays, too, can tend to coarseness, but this only really becomes noticeable when you're using long delays and high feedback values. One bonus for the impoverished samplist is that external audio can be routed through the A5000's effects, so you could use the A5000 as an extra effects unit.

It's all good stuff so far. Actually accessing the effects, however, requires you to (as the slogan says) Think Different. There are no 'global' effects processors, nor send‑return loops — the A5000 doesn't employ t he 'mixing desk' effects metaphor used by most modern instruments. At sample level, the sample's audio output is routed to the desired effect, and a secondary output allows it to be routed to a second effect in parallel. It's possible to override this routing at Sample Bank level (to send all the samples in a bank to the same effect, say) and with the Program level Easy Edit facility.

You could emulate a send/return loop, by using main and secondary outputs creatively: for example, use one routing option to send a sample's audio to the main stereo output, and the other to send the same audio to one of the effects. Set the effect's wet/dry balance to completely wet, and route that to the main output. More than one sample, or Bank, can be routed to one effect so, with a little bit of juggling of effect and dry sample output level, the finished result should approximate genuine global effects.

<!‑‑image‑>One last effects‑based niggle relates to editing effects in a multitimbral setup. The main Program window in Play mode lists Programs that have been assigned to parts in the multitimbral setup, and pressing the front‑panel Effect button takes you to a window where you can edit their effects. However, for some reason you can only do so if the setup's so‑called 'Master' part has been selected in the Program window. (The part designated Master shares its MIDI channel with the A5000's basic receive channel and is shown by a small 'M' next to its name.) If you try to edit effects with any other part selected, you can tweak parameters but a warning flashes up to say you're not editing from the Master Part and the changes will have no effect. Another niggle is that in neither of these windows — Program or Effect in Play mode — is there an indication of which effect is in force for which Program. You just get the list of the six effects to edit and have to remember which is assigned to each Program. If you don't remember — and you could be editing an old setup — you have to visit another page to refresh your memory. (A similar situation arises with samples and Sample Banks. There's no indication in the Effect window of what samples have been routed to which effects.)

Testing Times

The new display puts the A5000 miles ahead of the 3000 in terms of usability, but we still found the 5000 challenging initially. Not because the Yamaha method is bad or illogical — it's not — but mainly because Yamaha don't explain its fundamentals properly in the machine's documentation. If you've read the 'Going Deeper' section earlier, you will have more idea about where they're coming from than we did when we first got the A5000. A decent quick‑start guide would have speeded things up enormously. Apparently, one is on its way.

With or without such a guide, once you're familiar with how the A5000 works it's not only very powerful but also very fast. Sampling, trimming, looping and DSP operations are quick to perform, both with and without the use of the free software (see 'Freebies' box) and they take effect rapidly. Happily there's none of the display and control sluggishness which was identified in the SOS A3000 review.

<!‑‑image‑>Speaking of the display, as we've already said it's extremely useful, but Yamaha have sometimes tried to provide too much information, resulting in a busy feel. Conversely, sometimes we noticed a lack of graphic displays which would have helped us — a graphic approach to layering and splitting samples would have been a welcome use of the large screen, for example.

Verdict

There are some criticisms to level at the A5000's OS, one or two probably caused by the bolting on of a multitimbral mode that wasn't present in the A3000. Power samplists may also wish the A5000 had the 256Mb RAM capacity of the Akai S5000/6000. Still, the A5000 has to be a serious recommendation: there's just no arguing with its power and features at this price. We were also struck by the many thoughtful featurettes that make the whole business of sampling less of a technical chore and more of a creative activity.

Most importantly, the results achievable with the A5000 are breathtaking. Top sound quality combines with excellent synthesis facilities, meaty filters, wonderful effects and spontaneous, innovative sample‑manipulation tricks, to produce a sound‑designer's dream machine. Even if loading samples off CDs is the closest you come to sampling, there's no excuse for producing tired‑sounding timbres with the A5000.

Sampling Times

The A4000/5000's standard 4Mb RAM yields 47 seconds of mono, 44.1kHz sampling. With the maximum 128Mb installed (as four 32Mb SIMMs) a total sampling time of 25 minutes mono is available. However, the sample RAM is used such that the maximum length of a single sample is whatever will fit into 32Mb — six minutes and 20 seconds mono at 44.1kHz. If you had 64Mb installed you'd alternatively be able to have a stereo sample lasting six minutes and 20 seconds, because that just uses two 32Mb chunks side by side. So even though the samplers can record 25 mono minutes, it can't be contiguous audio. You should know whether this will be a problem for you.

Market Forces

Assessing the £1499 A5000 in relation to its competition is complicated, especially since the recent drop in the cost of Akai and Emu machines. On features and price the closest matches are Emu's e6400 Ultra (list £1799, cheaper on the street) and E5000 (£1299), and Akai's S5000 (£1299). The A5000 scores on its high standard polyphony (the S5000 and e6400 need fairly expensive upgrades to reach 128 voices, and the E5000 maxes out at 64), it equals the S5000 and e6400 on multitimbrality (the E5000 only goes to 16 parts), and does as well as Emu on RAM capacity. The S5000 wins there, with a giant 256Mb. On the effects front, the Yamaha's standard six processors beat both Akai and Emu, and its display is competitive (smaller than Akai's, bigger than Emu's).

The A5000 lacks digital I/O, as do the Emus (it's optional on all three), but it's cheap to add to the A5000, and the same board expands its analogue outputs to 10. The A5000 never gets as many outputs as the S5000 and e6400, which can achieve 16 with expansions, but both such expansions are quite pricey, especially the Emu one. The E5000 can be expanded to 12 outs from its base of four, but again the expansion isn't cheap. All four samplers have SCSI, but the S5000 has it times two. The S5000 also features direct‑to‑disk recording, which the others don't, and it has an ADAT interface option, like the e6400 Ultra.

The Yamaha and the Emus do best on sample format compatibility; the S5000 reads only WAV and S1000/S3000 formats. The Emus have the best sequencer, with 48 tracks and decent features, as opposed to basic playback devices on the Akai and Yamaha machines. All the samplers mentioned here can mount an internal HD (the Akai can have an internal CD‑ROM too), but the Yamaha also lets you swap its floppy for a Zip.

We can only compare on the basis of features and price, rather than the finer details of using these machines, and even then you can see how complex the whole subject is. Akai especially seem to have responded to Yamaha's presence very aggressively, and now that the S5000 is £1299, even with the expansion to add the extra 64 voices it manages to match the cost of the A5000 with the digital/extra output board, which can't be accidental! The Yamaha would still then have two extra outputs and more generous effects.

The current sampler market is a prime example of competition driving down prices, to the benefit of the end user (tough for people who bought an Akai sampler before the price changes!) and it's going to be hard to choose between the A5000, e6400 and S5000. We can only say we like the A5000 very much.

By the way, what is it with '5000'? Are there no other numbers for sampler manufacturers to use?

MIDI Matters

Useful real‑time MIDI control options have been provided for the A5000. At sample and Sample Bank level, incoming controllers and the Program LFO can be routed to any sample parameter (plus sample start address); six such routings are available. At Program level there are four routings, but here the controllers can only be assigned to effects parameters and a few Program‑level parameters such as S/speed and portamento rate.

The A5000 also transmits MIDI note and controller data: the six function buttons can send out MIDI notes, and five front‑panel knobs can output any MIDI controller, all on independent MIDI channels. The buttons are great for checking samples during editing (or triggering them in performance), and the knobs are perfect not only for tweaking A5000 parameters in real time, but for controlling parameters on other MIDI synths.

Freebie Sample CDS

<!‑‑image‑>The A5000 comes with extra bits that add more value to the package. For a start, you can write A5000‑format or audio CDs to an attached SCSI CD burner. There's also a simple sequencer on board. It has only sketchpad recording facilities, but can play back a full 16‑channel MIDI song file. A speed control offsets the tempo of the sequence, and that's about it.

Then there's those free sample CDs. Nine Yamaha‑format discs of samples, one general (covering various instruments) and eight themed, are supplied. The latter feature Strings/Choir, Piano/Keyboards, Brass/Wind Instruments, World/Latin instruments, Guitar/Bass, Real Drums, and 'Syntraxx'/Loops, plus a 'DJ/Producer Toolkit'. Documentation is skimpy, but they make a great starter collection, as long as you have more than the 4Mb basic RAM. They all seem to need a fair bit of memory.

The tenth disc supplied is a Mac/PC CD‑ROM which includes an A5000 control panel‑style editor and Tiny Wave Editor, an SMDI‑compatible sample‑recording and editing package developed by Yamaha. We used it to transfer samples from other sources to the A5000, as well as for fine‑tuning sounds recorded with the sampler. We found SCSI transfers speedy, even for quite long samples, and the interface easy to comprehend.

A5000 Editor is a software front end, mirroring all front‑panel operations with the exception of wave editing. It's very simple, with no librarian capabilities, and can only show one Program, sample bank or sample on screen at one time, but it's nonetheless effective. One inconvenience, though, is that when A5000 Editor loads in a Program list it never shows the Program names on screen, even though there's room for them.

<!‑‑image‑>This is the Record page just after sampling has been initiated, with a sample waveform arriving in the display. The graphic at the top right shows the sample's routing (mono in, coming from the left input), original key, and key range. There's an input‑level meter on the far right.

<!‑‑image‑>The Trim/Loop page. The waveform display has markers at top to show start and end points. The greyed marker is a loop start point. The loop end point can't be seen because it's at the same position as the sample end point. As you can see from the bottom right of the display, pressing knob 4 sets a start point on the fly (S‑Catch), while pressing knob 5 sets an end point (E‑Catch).

<!‑‑image‑>The Effect page. The area to the top left tells you where you are at any given time: in this instance, Play mode, effects setup B (effects 4‑6). The diagram on the right shows how the effects are routed between themselves and the output. Over on the left is a text list of effects 4‑6, which is where they can actually be selected and their outputs defined. Individual processors can be easily bypassed via knobs 3‑5.

A4000 Differences

At £1499 the A5000 presents excellent value, but the £999 A4000 arguably has an even better price‑performance ratio. Whether the differences — halved polyphony, multitimbral parts and effects on the 4000 — are worth the extra £500 is a question potential purchasers will be asking themselves. Certainly, many will be happy with 64‑note polyphony and 16‑part multitimbrality, but it's trickier to resolve the effects question. Only three blocks are provided for the A4000, and there's no option to expand. Effects freaks may find it hard to forgo the A5000's added power.

Other than these differences, the two machines are functionally identical. The A4000 even accepts the AIEB1 I/O expansion board. It's a shame Yamaha didn't emulate Akai or Emu here, and make the A4000 upgradable to A5000 spec.

Pros

- Fast and logical once you're familiar with how it works.

- Very good display.

- Diverse and generous effects.

- Speedy sampling routines.

- Creative DSP and editing options.

- Free CDs and software.

- Great value for money.

Cons

- You do have to think slightly different.

- 128Mb top RAM capacity doesn't match Akai.

- Only 4Mb basic RAM.

- Inadequate manual.

Summary

Priced within reach of newcomers, yet with a range of features that won't disappoint demanding samplists, this powerful machine sees Yamaha gaining confidence and establishing a strong foothold in the sampling market. If you're looking for a sampler, you must try it.