This month's Mix‑rescuees, Lee Thorpe and Katie Tomczynska.

This month's Mix‑rescuees, Lee Thorpe and Katie Tomczynska.

We mix a track twice in the search for the right feel, apply EQ techniques for clarity and sheen, and complete the picture with stereo width enhancement.

This month's mix session track “Another Day Calling” was sent in by SOS reader Lee Thorpe who, with singer Katie Tomczynska, make up the duo Turn Back To Spring. The main problem Lee was having was that they'd created a long build‑up at the end of the song, with multiple layered backing vocals, powerful guitars and pounding drums, but as the crescendo progressed to its final stages, he couldn't avoid the lead vocals being submerged and the mix as a whole was overloading crunchily. In addition, there was a general sense that the sonics weren't as open and sparkly as they could be, and for my part I felt that the upright bass sound was too uneven at the low end.

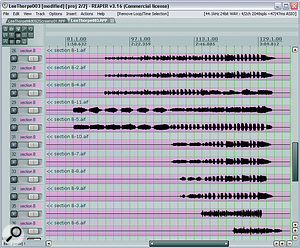

Here are the backing vocal parts as they arrived for Mix Rescue, and if you look at the waveforms you can see why Mike decided to mult them across a greater number of tracks. For example, notice that tracks 29 and 30 belong together to start with, but then at bar 107, track 29 suddenly has more in common with tracks 31 and 32, while track 30 matches track 28 more closely. Editing similar vocal sections to adjacent tracks made it much easier to control each group during the mix's heavily layered final section.As normal, once I'd imported the multitrack files into my Reaper‑based mix system, I spent some time troubleshooting timing and tuning issues before getting too involved with the real mix processing. That kind of handle‑turning work can easily bog down the more subjective mix process if you're not careful, so it's as well to get it out of the way early on if you can. In this case, I mostly just lined up the instrumental parts more tightly to the drums and tuned the backing‑vocal parts to produce a glossier blend. However, I also did some careful work with the lead vocal, to lock its tuning and timing more closely to the backing. This was partly because, although the band supplied me with re-taken vocals that improved on these aspects and upped the recording quality, I ended up going with the original tracks in the end — because the new tracks didn't seem to match the originals in terms of emotional immediacy. In such cases, I always prefer to use the more compelling performance rather than trying to make life easier for myself with a more polished but less involving take.

Here are the backing vocal parts as they arrived for Mix Rescue, and if you look at the waveforms you can see why Mike decided to mult them across a greater number of tracks. For example, notice that tracks 29 and 30 belong together to start with, but then at bar 107, track 29 suddenly has more in common with tracks 31 and 32, while track 30 matches track 28 more closely. Editing similar vocal sections to adjacent tracks made it much easier to control each group during the mix's heavily layered final section.As normal, once I'd imported the multitrack files into my Reaper‑based mix system, I spent some time troubleshooting timing and tuning issues before getting too involved with the real mix processing. That kind of handle‑turning work can easily bog down the more subjective mix process if you're not careful, so it's as well to get it out of the way early on if you can. In this case, I mostly just lined up the instrumental parts more tightly to the drums and tuned the backing‑vocal parts to produce a glossier blend. However, I also did some careful work with the lead vocal, to lock its tuning and timing more closely to the backing. This was partly because, although the band supplied me with re-taken vocals that improved on these aspects and upped the recording quality, I ended up going with the original tracks in the end — because the new tracks didn't seem to match the originals in terms of emotional immediacy. In such cases, I always prefer to use the more compelling performance rather than trying to make life easier for myself with a more polished but less involving take.

Throughout the mixing process, I also edited sections of the submitted audio files to separate tracks (sometimes referred to as multing) wherever I felt that they contained different musical features that would benefit from separate treatment. Backing-vocal tracks are common recipients for this kind of work, because vocals can perform so many different roles in an arrangement. That was certainly the case here, but in addition I ended up multing the snare and crash-cymbal parts for each of the two main sections of the arrangement, simply because the more saturated textures later on called for different mix settings. To some extent, this song is like two different arrangements stapled together, so it made sense to reflect that in my mix processing.

Moderating The EQ

If you're striving for clarity, it's worth high‑pass filtering most of the tracks in your mix. However, it also pays to refine the frequency and slope characteristics of each filter quite carefully to get just the right amount of low end, as in these EQ plots from the remix.

If you're striving for clarity, it's worth high‑pass filtering most of the tracks in your mix. However, it also pays to refine the frequency and slope characteristics of each filter quite carefully to get just the right amount of low end, as in these EQ plots from the remix.

When it came to bringing extra clarity and sheen to the production, there wasn't really any silver bullet involved; it was largely just a question of careful EQ and a blend of various send effects. As far as EQ was concerned, high‑pass filtering featured on all but a small handful of tracks. Although many of these filters were left at a 'safety setting' of 20Hz, to catch any DC and inaudible rumbles, I also refined the filter setting where necessary, to take out any low‑frequency parts of individual sounds that didn't seem to be essential to their place in the mix. Mostly, these more audible roll‑offs began in the 100‑200Hz region, and affected tracks such as the opening mandolin, the echo‑like synth effect, and a small selection of the electric guitar and vocal parts during the final section. A few tracks lost more of their low spectrum: the high 'Oh‑oh' backing vocal line, which rolled off around 450Hz, and the cymbals, whose LF energy below 1kHz I reduced during the end section, where it was veiling other more important mix details. And let's not forget the effects returns: reverbs and delays, in particular, can afford to have reduced sub‑400Hz energy if you're trying to preserve mix real-estate.

The default ReaEQ high‑pass filter in Reaper is quite good for these jobs, because it has fully variable frequency and bandwidth controls, so you can already quite freely adapt the curve to tailor the low end of a given sound before you reach for any additional shelving or peaking bands. The rest of the EQ consisted of a few narrow peaking cuts (to tackle an over-prominent 324Hz snare resonance and some 7‑8kHz harshness in the hat and cymbal parts), and then a series of fairly subtle tonal‑balance changes using further EQ bands — nothing beyond 4dB of cut or boost, and using very wide‑bandwidth shelving and peaking filters. I could bore you with all the specific settings, but that probably wouldn't give you anything to take away with you for your own productions: the exact settings are less important than the principle behind them. I was looking for a level for each frequency range of each instrument where it poked out over less important tracks without obscuring more important tracks.

The default ReaEQ high‑pass filter in Reaper is quite good for these jobs, because it has fully variable frequency and bandwidth controls, so you can already quite freely adapt the curve to tailor the low end of a given sound before you reach for any additional shelving or peaking bands. The rest of the EQ consisted of a few narrow peaking cuts (to tackle an over-prominent 324Hz snare resonance and some 7‑8kHz harshness in the hat and cymbal parts), and then a series of fairly subtle tonal‑balance changes using further EQ bands — nothing beyond 4dB of cut or boost, and using very wide‑bandwidth shelving and peaking filters. I could bore you with all the specific settings, but that probably wouldn't give you anything to take away with you for your own productions: the exact settings are less important than the principle behind them. I was looking for a level for each frequency range of each instrument where it poked out over less important tracks without obscuring more important tracks.

That said, there are a few tips which help in this otherwise rather subjective process. The first is to consider dealing with any overall mix‑tone changes using a single equaliser plug‑in inserted in your master bus. This is something for which I typically use URS's Console Strip Pro, because it offers fully variable controls as well as various different analogue‑modelled tonal options. Whatever EQ you decide to use, though, just remember that your whole mix is going through it, so don't skimp on quality. With this month's remix, I noticed that many of the sounds felt a bit muffled, so I decided to lift the whole frequency response above about 1kHz, using around 6dB of boost from the gentlest high shelf (Q = 0.25) at 14kHz. What this meant was that I didn't feel the need to whack on loads of high‑frequency boost with less snazzy channel EQs, which helps keep the mix sounding smoother. On a psychological level, too, if you consistently have to crank one band of your channel EQ, you're probably less likely to exercise as much caution with any other bands you apply.

That said, there are a few tips which help in this otherwise rather subjective process. The first is to consider dealing with any overall mix‑tone changes using a single equaliser plug‑in inserted in your master bus. This is something for which I typically use URS's Console Strip Pro, because it offers fully variable controls as well as various different analogue‑modelled tonal options. Whatever EQ you decide to use, though, just remember that your whole mix is going through it, so don't skimp on quality. With this month's remix, I noticed that many of the sounds felt a bit muffled, so I decided to lift the whole frequency response above about 1kHz, using around 6dB of boost from the gentlest high shelf (Q = 0.25) at 14kHz. What this meant was that I didn't feel the need to whack on loads of high‑frequency boost with less snazzy channel EQs, which helps keep the mix sounding smoother. On a psychological level, too, if you consistently have to crank one band of your channel EQ, you're probably less likely to exercise as much caution with any other bands you apply.

Mike used the high‑quality EQ in URS's Console Strip Pro to lift the high end of the mix in general, rather than applying similar boosts from lower‑quality plug‑ins on each channel.Sticking with the psychology for the moment, a common pitfall with EQ is that you reach for boosts before cuts, and this is something else that brings with it a danger of over‑EQ'ing. Boosts don't just affect the frequency balance: they also make the sound, as a whole, louder — and for this reason even badly judged EQ settings can appear to improve the audibility of a sound in the mix. On the other hand, if an EQ cut improves matters, then you can be pretty sure that you're not fooling yourself. It's not that boosts don't have their place when using EQ (they're a quicker route to certain response shapes, for instance), it's just that it's trickier to remain objective when using them.

Mike used the high‑quality EQ in URS's Console Strip Pro to lift the high end of the mix in general, rather than applying similar boosts from lower‑quality plug‑ins on each channel.Sticking with the psychology for the moment, a common pitfall with EQ is that you reach for boosts before cuts, and this is something else that brings with it a danger of over‑EQ'ing. Boosts don't just affect the frequency balance: they also make the sound, as a whole, louder — and for this reason even badly judged EQ settings can appear to improve the audibility of a sound in the mix. On the other hand, if an EQ cut improves matters, then you can be pretty sure that you're not fooling yourself. It's not that boosts don't have their place when using EQ (they're a quicker route to certain response shapes, for instance), it's just that it's trickier to remain objective when using them.

Furthermore, if I find myself wanting to apply lots of boost, it's often an indicator for me that the source needs some kind of tonal adjustment beyond mere frequency balancing, so it cues me to investigate other processing avenues. In this month's remix, the EQ was mainly about balancing the elements of the mix in the frequency domain, so I was happy to use Reaper's ReaEQ for most of this. On those few occasions where I felt that a frequency region of an instrument needed some subjective enhancement beyond just rebalancing, I turned to more characterful 'character' EQ plug‑ins instead. So Stillwell Audio's 1973 helped me add some low mid-range warmth to the lead vocal while steering clear of the woolly sound that ReaEQ delivered when attempting a similar change, while the same developer's assertive‑sounding Vibe EQ was great for slightly hardening both the main bass sound and the outro's 'Oh‑oh' backing vocals, drawing them both a fraction forward in the mix.

The Last Line Of Defence

Despite the general kid‑gloves EQ approach, there was one particular EQ issue that was more troublesome and required powerful specialist processing to address: the unevenness in the bass tone. The initial problem appeared to be that the fundamental frequencies of the four notes in the part were at very different levels: the top two notes dominated the lower two. A few extremely narrow peaking filters were able to help here by pulling down the level of the upper notes, while a slightly wider peaking boost at 50Hz helped fill out the lower notes.

However, it swiftly became apparent to me that it wasn't just the levels of these fundamentals that were giving me grief; it was their level envelopes too. The fundamentals at 50Hz and 75Hz both seemed to decay much quicker than the other two fundamentals at 55Hz and 82Hz, so even with balancing equalisation, the sound still felt very uneven. What I really wanted was a way to compress the level envelopes of just the fundamental frequencies. Normal full‑band compression clearly wasn't going to be the answer here, because that wouldn't be able to adjust for the real‑time frequency‑balance changes. One solution might have been to use a multi‑band compressor, carefully placing a crossover between the upper and lower pairs of fundamentals, and also between the upper fundamentals and the remainder of the bass harmonics. However, the fundamentals in this case were all within an octave of each other, and few multi‑band compressors have crossovers steep enough to provide serious control over such small frequency ranges.

These screenshots show the processing used to sort out a persistent unevenness in the bass line: a combination of Platinumear's IQ4 dynamic EQ and Reaper's internal ReaEQ.Which brought me to one of my last lines of defence: dynamic EQ. This is not something that I use every day, because it can be rather long‑winded to set up, but it can really bail you out when more traditional and convenient processing choices wave the white flag. Where normal static EQ has gain controls for each band that stay where you put them, you can configure the gain stages in a dynamic EQ to respond to the signal level in that band, much as the gain element of a dynamics device would do. A single band of dynamic EQ is the basis of many software de‑essers, allowing you to compress the high‑frequency sibilant peaks in a vocal independently of the rest of the signal, but there are also more fully‑featured general‑purpose dynamic EQs available, such as TC Electronic's Powercore Dynamic EQ plug‑in and 112dB's Redline EQ. For this case, however, I went for the plug‑in that I'm most familiar with: IQ4's freeware Platinumears dynamic EQ.

These screenshots show the processing used to sort out a persistent unevenness in the bass line: a combination of Platinumear's IQ4 dynamic EQ and Reaper's internal ReaEQ.Which brought me to one of my last lines of defence: dynamic EQ. This is not something that I use every day, because it can be rather long‑winded to set up, but it can really bail you out when more traditional and convenient processing choices wave the white flag. Where normal static EQ has gain controls for each band that stay where you put them, you can configure the gain stages in a dynamic EQ to respond to the signal level in that band, much as the gain element of a dynamics device would do. A single band of dynamic EQ is the basis of many software de‑essers, allowing you to compress the high‑frequency sibilant peaks in a vocal independently of the rest of the signal, but there are also more fully‑featured general‑purpose dynamic EQs available, such as TC Electronic's Powercore Dynamic EQ plug‑in and 112dB's Redline EQ. For this case, however, I went for the plug‑in that I'm most familiar with: IQ4's freeware Platinumears dynamic EQ.

The first step I took with IQ4 was to set two of its peaking bands to their narrowest setting (Q = 6.5) and park them at 50Hz and 75Hz respectively. I then set the band's gain controls to act like compressors, going for a 4:1 ratio to try to get a firm handle on the levels. There followed a fair amount of juggling of Threshold, Attack, and Release controls in each band before I was happy I was making a positive impact. The release times seemed particularly important, as the 75Hz fundamental didn't seem to tolerate as fast a release time as the 48Hz frequency before it started sounding excessively 'tampered with'.

Wider Than Wide

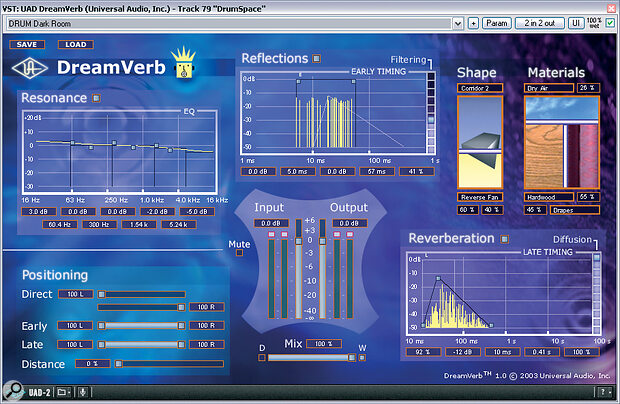

As I said before, the send effects were quite an important part of the remix, particularly because they really fleshed out the stereo picture, making the production, as a whole, feel airier. Only three of these effects were reverbs, though: one a fairly short drum room from the UAD2's Dreamverb plug‑in, to glue the drum samples, strings and lead vocal into the mix; another a long plate from the UAD's renowned Plate 140 algorithm, the purpose of which was to add extra sustain and expansiveness to many of the non‑percussive instruments; and the third a fairly short, tail‑free, blending treatment from the shareware Smartelectronix Ambience plug‑in.

Three reverbs were used for this mix: Universal Audio Dreamverb and Plate 140, and Smartelectronix Ambience.

Three reverbs were used for this mix: Universal Audio Dreamverb and Plate 140, and Smartelectronix Ambience.

All of these filled out the stereo image to a certain extent, but I felt there was more scope here, so I set up a pair of stereo modulation effects as well, using those trusty old freeware workhorses from Kjaerhus Audio: Classic Chorus and Classic Phaser. These have a nice stereo mode, where the modulation is different in the left and right channels — and this is great for adding an ethereal stereo 'halo' around all sorts of sources. It does pay, in most situations, to go for quite subtle settings, though: keep the modulation depth parameter below about 20 percent, steer clear of modulation rates over about 1Hz, and in the case of the Phaser, go easy with the feedback control too. Be warned also that the software's default wet/dry setting is only 50:50, so if you're (sensibly) using either plug‑in as a send effect you should move the wet/dry knob to 100 percent wet, to avoid any change in dry track levels as you turn up effect sends.

Kjaerhus Audio's great freeware Classic Chorus and Classic Phaser plug‑ins did a lot to fill out the stereo picture, although the settings were fairly subtle, as you can see in these screenshots.Two delay patches played a part, too. The first, a tempo‑sync'ed delay that I have on hand for all my mixes, helped by virtue of being a true stereo delay, in other words an algorithm that preserves the stereo imaging and panning of the dry tracks in its delay repeats. Some delay effect plug‑ins sum their inputs to mono before creating their delay taps, and even when this isn't the case it can be difficult in some software mixing environments to set up a suitable stereo effect send; in either case, the resulting mono delay return can easily end up narrowing the mix, by giving central echoes to off‑centre sounds. The second delay patch was a ping‑pong delay, which helped add a hint of rhythmic stereo interest to the mandolin, echo synth and piano.

Kjaerhus Audio's great freeware Classic Chorus and Classic Phaser plug‑ins did a lot to fill out the stereo picture, although the settings were fairly subtle, as you can see in these screenshots.Two delay patches played a part, too. The first, a tempo‑sync'ed delay that I have on hand for all my mixes, helped by virtue of being a true stereo delay, in other words an algorithm that preserves the stereo imaging and panning of the dry tracks in its delay repeats. Some delay effect plug‑ins sum their inputs to mono before creating their delay taps, and even when this isn't the case it can be difficult in some software mixing environments to set up a suitable stereo effect send; in either case, the resulting mono delay return can easily end up narrowing the mix, by giving central echoes to off‑centre sounds. The second delay patch was a ping‑pong delay, which helped add a hint of rhythmic stereo interest to the mandolin, echo synth and piano.

In addition to the widening by-products of all these effects, I was also running my favourite dedicated widening send effect: a pitch‑shifter delay chain that's as old as the hills, although the exact settings vary slightly from engineer to engineer: left‑ and right‑channel delays of 11ms and 13ms respectively, pitch‑shifted by ‑5 and +5 cents respectively. This can work very well for lead vocals in some styles, although in this case I used very little of it for that, because it made the voice sound too chorused, applying it instead to the mandolin, string and echo synth parts.

Secrets Of Build‑up

The build‑up for the final section was almost a separate mixing job in itself, but much of it nonetheless relied on similar EQ and effects approaches to provide the overall clarity and width, along with judicious automation to maintain an appropriate balance throughout. So why did the band have problems with their version? There were a number of reasons, the first of which was that neither the backing vocals nor the guitars were tightly enough in tune. The looser the tuning of a set of instruments, the more space they eat up in an arrangement, and the less well they blend together. Naturally, there's a balance to be struck with tuning, because ironing out pitch variations completely can suck the life out of your mix, but I felt that there was still room for improvement before there was much risk of that pitfall.

The vocals were easily taken care of via a short appointment with Celemony's Melodyne, but the polyphonic tuning disagreements between the guitar parts seemed to be beyond even the capabilities of Celemony's latest DNA processing. The guitars had also been fairly heavily driven, such that they pretty much just dissolved into noise by the end of the track, so I quickly realised that the most promising avenue for me was to replace some of the parts. In the end, I kept the band's main original guitar part, and then supplemented it with several additional supporting parts, ably played by my friendly assistant Dan Jeffries (thanks Dan!) through IK Multimedia's Amplitube.

Another problem with the original guitar parts was that they only really built up in terms of volume, and there's only so far you can go along that route before you run out of headroom. Mixing slow build‑ups is as much about illusion as about sheer level, so it helps to have some arrangement, width and timbral changes you can bring into play as the build progresses. For this reason, I didn't just ask Dan to replicate the existing guitar parts, but rather asked him to add a new unique part for each section of the build, so that the thickness and tone of the guitar texture slowly increased along with the signal levels. In a similar vein, the band had also made things difficult for themselves by having too much going on in the arrangement from the outset, especially in terms of guitars and drums. If you're going to pull off this kind of long crescendo, you've got to start off as small as you dare in order to leave the maximum room for manoeuvre.

Timing had as important a part to play as tuning, because the original drum parts had been played in by hand, and occasional inconsistencies were making the build‑up feel as if it was stumbling in places, where this section of the song clearly called for the sense of inevitable momentum that comes from tighter timing. Of course, the rest of the parts had been recorded along to the original drums, so they also needed tweaking back into alignment once the drums had been made more consistent.

This screenshot shows the original guitar arrangement: three fairly heavily overdriven guitar parts playing together throughout, and the only thing really changing being their overall level. In order to give a better illusion of crescendo without using up as much signal headroom, Mike opted to retain only one of these original parts, supplementing that with additional, simpler overdubs to bulk up the texture more progressively.

This screenshot shows the original guitar arrangement: three fairly heavily overdriven guitar parts playing together throughout, and the only thing really changing being their overall level. In order to give a better illusion of crescendo without using up as much signal headroom, Mike opted to retain only one of these original parts, supplementing that with additional, simpler overdubs to bulk up the texture more progressively.

When the build‑up itself seemed to be working, an ancillary challenge was somehow to keep the lead vocal's lyrics from being swallowed up in the final mix maelstrom. The prominent guitar distortion and cymbals at the end of the track were intent on obscuring them completely. Obviously, automation provided some tools for overcoming this obstacle, but the situation was extreme enough that I decided to add in some processing 'sleight of hand'. I sent a small amount of the guitar and cymbal tracks to a separate mixer channel containing a gate, and triggered that gate from the lead vocal. The gate's output was then focused into the 1‑7kHz range with Slim Slow Slider's Linear Phase Graphic EQ (a linear‑phase EQ works best), summed to mono using Voxengo's freeware MSED, and then polarity‑inverted.

The result of all this was a signal which, when added back into the mix, partially phase‑cancelled the guitars and cymbals whenever the lead vocal was present — but only in the 1‑7kHz region and in the centre of the stereo image. The level of the gated signal determines how much cancellation you get in this setup, so I slowly rode the return fader to ensure that the cancellation only happened when it was really needed, towards the end of the song. Not something you pull out of your bag of tricks every day, but it seemed to work quite well here, and allowed me to maintain the vocal intelligibility at a lower level in the mix, thereby better supporting the illusion of a powerful backing track.

A Time For Everything

If you've thought carefully about your arrangement (as Turn Back To Spring clearly had) and you've sorted out any necessary edits, you should find that drastic EQ is mostly unnecessary, in which case don't be afraid to leave tracks well alone when they already balance fine as they are. By the same token, though, there are times when it's handy to have a stock of more advanced tricks that can bail you out when more traditional mix‑processing tools struggle to cope. So if you've not tried dynamic EQ or triggered phase‑cancellation yet, give them a whirl — you never know when they might save your bacon!

If At First You Don't Succeed...

Unusually, this month's track actually went through two remixes, the second of which I've spent this article discussing. Why only the second? Well, for the first version I pursued a more lo‑fi and guitar‑heavy vision, inspired by my impressions of some of the band's stated reference tracks (including cuts by Goldfrapp and Sigur Ros), and this took the sound quite a long way away from the band's original presentation. In some cases, this kind of input is what musicians are hoping for from a mix... but on this occasion it clearly wasn't! So I zeroed the mix and started again from scratch.

Now, it's very easy to get narked if this happens to you, but you have to remember, as a mix engineer, that it's the artist's music, so only they can really know what works and what doesn't. No matter how good your mixing skills, you can still only make an educated guess at what the artist wants to hear. If you guess wrong, you just have to take a deep breath, swear a bit (well, that helped for me, at least!), and then use the experience to guess better the second time around! For what it's worth, though, I've included my 'Mk I' mix with this month's audio files, so you can hear how different it sounds from the final remix we all eventually agreed upon.

Rescued This Month

SOS Reader Lee Thorpe began collaborating with Katie Tomczynska while studying on the British Academy of New Music's Artist Development Program, and they now write and perform together under the moniker Turn Back To Spring. The song featured in this month's column, 'Another Day Calling', was the one that really brought them together as co‑writers, and although they loved the musical ideas in the song, they just didn't feel they'd quite got the mix right. Despite this, the song recently won the Michael Kamen award for Outstanding Achievement in Composing for Film. Although both Lee and Katie took an equal role in the writing process, Lee focused more on the recording and production side, while Katie worked on the intricate vocal arrangement. Additional parts were added by Luke Hannam (bass), Ben Edwards (mandolin), and David Langley (guitar).

SOS Reader Lee Thorpe began collaborating with Katie Tomczynska while studying on the British Academy of New Music's Artist Development Program, and they now write and perform together under the moniker Turn Back To Spring. The song featured in this month's column, 'Another Day Calling', was the one that really brought them together as co‑writers, and although they loved the musical ideas in the song, they just didn't feel they'd quite got the mix right. Despite this, the song recently won the Michael Kamen award for Outstanding Achievement in Composing for Film. Although both Lee and Katie took an equal role in the writing process, Lee focused more on the recording and production side, while Katie worked on the intricate vocal arrangement. Additional parts were added by Luke Hannam (bass), Ben Edwards (mandolin), and David Langley (guitar).

Remix Reactions

Katie: "I'm really happy with the way Mike has given my vocals such clarity and presence within the outro of this track. I think he has created space and depth in the stereo mix, which was exactly what we needed. I am also pleased with the mixing of the bass and the drums, as they were competing with my vocals rather than complementing them.”

Lee: "It took a while to get to the final mix, but it was certainly worthwhile. The difference between the first draft mix from Mike and the final product is vast. Although his idea of what the track should sound like was initially very different from mine, he soon realised our vision. Overall, the sound of the vocal has much more depth and clarity. Things are not competing quite as much as they were before; this is especially evident with the drums and bass, and in the giant crescendo towards the end. Mike has worked wonders, and it now sounds exactly as I always imagined it could.”

Audio Files On-line

We've placed a number of audio files on-line to demonstrate the differences between the original mix and Mike's reworking of the track: /sos/may10/articles/mixrescueaudio.htm