There comes a point when tinkering with your mixes won’t improve them — it could even damage them. But just how do you know when it’s time to let go?

There’s a famous quotation, often attributed to Leonardo da Vinci: “Art is never finished, only abandoned.” In other words, creative projects aren’t like mathematical equations that can be solved. There will always be more that the creator could do, but since there’s no ‘right’ answer they’ll never arrive at a clearly defined end point. So they must learn to live with the fact that they may never be truly satisfied with their creation, and figure out how to recognise when it’s time to let go and move on. It’s a sentiment that applies as much to mixing music as to any creative endeavour...

Unfortunately, today’s music‑making technology practically invites us to keep on refining our mixes, and strive to inch ever closer to some vaguely defined notion of ‘perfection’. Knowing when a mix is ‘done’ can be even more challenging for those who are still feeling their way into mixing, since they can be tempted to try out lots of new and exciting techniques in a constant chase for results that sound ‘better’ or ‘more professional’. But, at some point, the experimenting must stop, and your focus needs to shift towards ‘signing off’ the mix. That means learning how to wrap things up in a practical sense, but also how to move on emotionally from a mix — and I can’t stress how incredibly important this is in your development as a mix engineer!

Can You Feel It?

So, just how do you know when a mix is finished? Well, if you’re mixing for an artist (or any other client), the short and obvious answer is “when they’re happy!” But if you’re to feel at all satisfied and to develop as a mix engineer, it’s important that you’re also happy with the mix before you send it off. And, of course, maybe as well as being the engineer, you’re the artist — in which case, how do you know when you’re content to call it a day?

In my experience, there’s rarely one clear moment in which you feel that you’ve suddenly ‘cracked’ the mix, and find yourself punching the air and dishing out high fives to unsuspecting strangers in the street. More likely is one of a few different scenarios, and the most gratifying is when you sense that the music you’ve been engrossed in mixing starts to take on a life of its own. It’s when you start to feel more like a listener enjoying the music, and less like an engineer trying to shape it. Maybe the chorus stirs some sense of feeling, perhaps a particular lyric begins to resonate and the hairs on your neck start to tingle. Or it might simply be that you notice you’ve subconsciously started nodding your head or tapping your foot to the beat.

I’ve learnt to take such feelings seriously, because at this point mixing can become more about protecting and nourishing this often‑indefinable quality in the music. On that note, another scenario might be seen as the flip side of the same coin: you notice a growing sense that you might be ‘overworking’ the mix, and thus making it worse. In that case, maybe it’s time to stop throwing more plug‑ins and production tricks at the project, and make a conscious effort to tie things up. More pragmatically, an end point might be driven by client deadlines, or a simple need to get on and get a mix finished so that you get paid.

Now, in any of those scenarios, we absolutely still need to feel moved by the music. That’s the whole point! But when there’s a lot to do and we don’t have the time to reflect and experiment, we can, hopefully, lean on our experience and some routines to allow us just enough space for creativity while ensuring we deliver consistently good work.

I deliberately draw a metaphorical line under things, take stock and change my perspective... and to help me make this shift I’ve developed a few routines.

Shifting Gears

For clarity, let’s say we’re talking about ‘the last five percent’ of a mix, and how we take the good work we’ve done and move serenely to the point where we’re happy to send it off to the artist, or maybe even invite them into your studio. At this stage, I find it helpful to make a conscious decision to shift gears, and stop striving/pushing for ‘something more’. I’m happy to do that because I’ve decided that I like where I’ve got to. I’ve done my experimenting, explored some blind alleys. I feel confident that, at least to my own taste, I’ve arrived at a point where the music has some impact and is making me feel something. Or perhaps I simply feel that I’ve respectfully stayed out of the way of the song while giving it a little polish.

So at this point, I deliberately draw a metaphorical line under things, take stock and change my perspective. Like anything that requires self‑discipline, this can be hard, and to help me make this shift I’ve developed a few routines over the years. I find that these help me a great deal to finish a mix strongly, and feel that bit more confident about handing it over to someone else.

A good set of studio headphones may well tell you something useful about your mix as it nears the final stages — but you do need to be careful about what you tweak as a result.

A good set of studio headphones may well tell you something useful about your mix as it nears the final stages — but you do need to be careful about what you tweak as a result.

I mix primarily in my studio, on a single set of speakers. Whilst I’m very happy with my monitoring setup, in these later stages of a mix I make a point of having two or three listens through on my good‑quality studio headphones. I nearly always spot a few things, such as a panning issue, some amp noise hanging over a ‘stop’ section, or a stereo effect that worked on speakers but seems a bit overbearing on headphones. Obviously, I’ll attend to those. I may also make some very minor changes with EQ, but I try hard not to start tinkering and experimenting again, because I find that can lead me to second‑guess what I’ve already done.

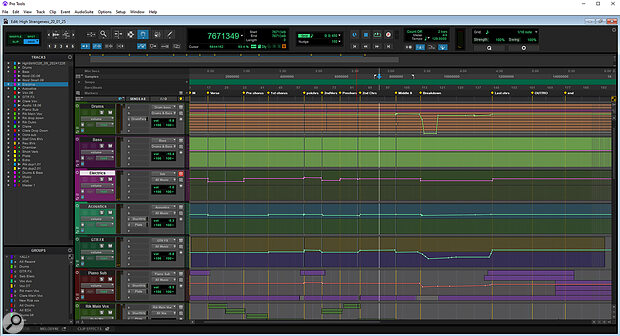

Whilst I’m in this mind set, I’ll take a closer look at my Pro Tools session and double‑check a few things. I might well be working on different projects simultaneously, so want to get the current mix into a state where I can return to it next time (often a day, but perhaps a week or months later) and be able to make tweaks or revisions for my clients in a timely manner. I want to find myself looking at a screen that almost forces me to consider the mix in a broader way, and doesn’t tempt me to look at individual tracks and dive back into the mix.

As well as being useful on a practical level, going through your project and organising everything into a ‘macro view’, with tracks in folders and everything in view on the arrange page, can help to shift your mental focus.

As well as being useful on a practical level, going through your project and organising everything into a ‘macro view’, with tracks in folders and everything in view on the arrange page, can help to shift your mental focus.

So, I’ll check for any issues with the routing, print any hardware processing I’ve used, generally look to bring some order to anything I may have missed during the more carefree mixing stages when I was throwing the metaphorical paint around, and seek to narrow down the tinkering options in my DAW. Most DAWs, for example, let you put groups of tracks in folders or show/hide different tracks, and now’s the time to make use of such features. (If you’ve been using folders all along, then maybe consider closing them all, so that the visual focus is on the bigger picture). This has developed into a really important stage of the mix for me — it really helps me mentally to move things on.

Checks & Balances

After that shifting of gears and future‑proofing, it’s good to approach the next stage with fresh ears. That could be the next day, or it could just mean taking a listening break while you take the dog out, make a cup of tea, or whatever — something that allows your ears to recalibrate.

Auratone‑style ‘grotboxes’ can be useful, but at this late stage there’s a risk that the big change in sound could negatively impact your mood!In terms of what I actually do to my mix, my focus now is about making sure that the things I like about it will translate when played away from my studio. This often involves detailed level automation, and might require some more technical moves to create the space the main singers or instruments need. As you get more mixing hours under your belt, especially if you have a settled mixing setup, you’ll spend less of this time on the fundamentals of vocal or bass levels, and more on seeing just how far you can push certain elements of your mix to create interest, impact and excitement on lesser playback systems.

Auratone‑style ‘grotboxes’ can be useful, but at this late stage there’s a risk that the big change in sound could negatively impact your mood!In terms of what I actually do to my mix, my focus now is about making sure that the things I like about it will translate when played away from my studio. This often involves detailed level automation, and might require some more technical moves to create the space the main singers or instruments need. As you get more mixing hours under your belt, especially if you have a settled mixing setup, you’ll spend less of this time on the fundamentals of vocal or bass levels, and more on seeing just how far you can push certain elements of your mix to create interest, impact and excitement on lesser playback systems.

It’s common to have some kind of lower‑fidelity playback system in your mixing space as a secondary reference. This might include some kind of small consumer Bluetooth speaker or the classic Auratone‑style ‘grotbox’, but although the latter can be useful at other times, I’d think twice about using them for these final checks and balances. Why? Well, when you’re trying to wrap up your mix, something that sounds so dramatically different or lo‑fi can easily destroy your morale or lead you down an unhelpful path.

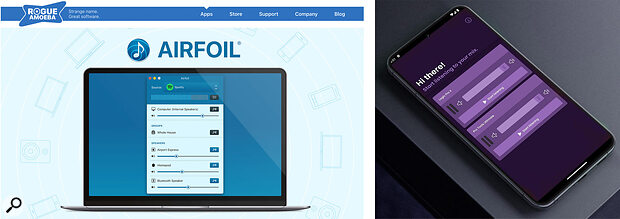

Personally, I find some half‑decent, ubiquitous modern playback systems are best for this stage. I often now use some Apple AirPods, which are a likely way in which my client or artist will hear the mix for the first time — there’s some neat software that allows you to get your DAW signal to AirPods or a phone over Bluetooth. I’ve been using Rogue Amoeba’s Airfoil, for example, and keep meaning to check out Sound on Digital’s Mix To Mobile plug‑in, which looks promising.

It can be useful to use ubiquitous full‑range secondary references such as Apple AirPods, and software like Rogue Amoeba’s Airfoil and Sound on Digital’s Mix To Mobile can make that pretty easy.

It can be useful to use ubiquitous full‑range secondary references such as Apple AirPods, and software like Rogue Amoeba’s Airfoil and Sound on Digital’s Mix To Mobile can make that pretty easy.

But what are we actually listening out for? When I listen on my studio monitors to music that I’ve previously enjoyed as a listener elsewhere, I’m often struck by just how ‘out there’ or ‘wonky’ some elements of the mix can appear. Such wonkiness really doesn’t matter here: it’s the emotional impact on the listener that’s all‑important.

Put another way, I’d much rather a client questioned a bold creative decision I’d made than that they think my mix safe or boring! So, I’m really on the lookout for anything about the mix that I was really enjoying on the studio monitors, but now feels a bit watered down. Consumer devices can’t deliver everything top‑end speakers can — the sense of separation, tight bass, and so on — but they you can certainly tell if a chorus isn’t ‘kicking in’ to deliver an emotional impact, or if a kick drum you worked hard on to lay the foundation of the groove seems a bit lost when there’s less LF extension. Any such changes to the emotional impact of the mix are hugely important, and definitely need addressing. I’ve learnt to enjoy seeing just how far I can push the automation into chorus sections, or make the main mix elements sit ‘loud and proud’ before it starts to be too much.

Honest, Reliable Feedback

I can’t stress enough just how beneficial it is if, when you’re in the early stages of your mixing journey, there are a couple of people you can lean on to give honest, critical feedback and help you build your confidence. For example, there are a couple of young engineers who’ve helped me or paid for my services in the past, and made some effort to establish a relationship with me, and I’m always happy to offer thoughts or suggestions if they send me a mix. They’re not really looking for a detailed critique, but might just need encouragement to get on and finish a mix that sounds great, or I might offer just two or three points for them to consider (eg. panning issues, or how the vocal is ‘sitting’ with the music).

I can’t stress enough just how beneficial it is if there are a couple of people you can lean on to give honest, critical feedback and help you build your confidence.

There are some great online communities that can help with this, of course, but you’ll tend to find that you get all sorts of views from all sorts of people, and sometimes so many detailed suggestions that you start to completely question what you’re doing! It will never be as good as developing real‑world relationships with audio professionals who get what you’re trying to achieve. This is one of many good reasons for still using a human mastering engineer; a good one who really cares will be more than happy to help you with observations about your mixes, as well as making you sound better.

Sharing Your Mix

We’ve looked at some ways that we might personally go about getting a mix finished to our own satisfaction, but when you’re mixing for other people they need to be happy too. ‘Other people’ might mean the artist or, at a higher level, management or labels. It might mean several people, potentially with different ideas, and it’s worth noting that a typical band today will have at least one member who’s an aspiring engineer and may well critique your work from that perspective. In short, it can be a minefield. After many years of running a studio I could probably write a book about the mix feedback scenarios in which I’ve found myself, but I can offer a few suggestions here.

The first is around tone — not the musical type, but how you communicate. For example, when sending a mix to a client, your choice of words in an email can influence how they feel on hearing the mix. Keeping your correspondence short, friendly, positive and complimentary seems to work — what’s the point of describing what you’ve done or drawing attention to details you’re worried about? What you can do is try to put them in a positive frame of mind, so perhaps slip in a mention of how much you enjoyed an aspect of the song or performance. Similarly, with some clients I might suggest that they can take their time to listen, and not feel that they need to get back to me straight away. If it’s a band, I’ll also often suggest that they take the time to compare notes and collate any feedback, before firing a bunch of potentially conflicting suggestions back at me (obviously don’t put that last bit in the email!).

We usually send mix files electronically these days, and the above paragraphs assume you’re doing that. But I’m a firm believer that just because we can do things remotely it doesn’t mean we should. Most of the well‑known mix engineers we revere will have cut their teeth in an age when artists went into studios, and they’ll lean on that experience even when mixing remotely. So if you’re mixing with clients who are reasonably local, why not invite them to your mixing space to hear the mix (assuming it’s practical to do so)? It can be pretty unnerving if you’re unused to it, but you can learn a lot about how bands and artists perceive their art, and it can be a great deal of fun to boot. This approach often helps me reach the finish line more quickly, and it can be amazing just how different a mix sounds to you with other people in the room: you’re forced to hear it almost through their ears!

Just because you can work remotely, it doesn’t mean you have to: if you have the chance to get artists into your studio to listen to the mix or work through revisions, you can often learn a lot about them — and often tie things up more quickly too.

Just because you can work remotely, it doesn’t mean you have to: if you have the chance to get artists into your studio to listen to the mix or work through revisions, you can often learn a lot about them — and often tie things up more quickly too.

Feedback & Revisions

Now, hopefully, your client likes the mix just as much as you do, in which case great. But, as sure as night follows day, at some point your mix will be greeted with a negative or lukewarm reaction. That can really sting, but although a little self‑doubt is a natural reaction it’s really important that you don’t let yourself sink into a pit of despair. You need to keep things in perspective and learn how to process all feedback in a positive way, so you might find it reassuring to remember that mixers working much higher up the ladder than you still get negative reactions on occasion, and still question what they are doing!

In terms of what you can do in a practical sense, you must first gauge pretty quickly just how far apart you and the client are, and whether the situation is retrievable. The reasons for such a reaction vary, and you need to figure out exactly what’s actually going on (this is not made easier if everything’s done over email!), and whether you can realistically sort things out. If you find that you’re miles apart in terms of expectations and taste, it could well be better just to take it on the chin: suggest that you might not be the best person to mix this particular project. But you might, for instance, discover that the singer felt bad about their performance once they heard it presented more clearly in the mix. In such scenarios, you often won’t need to do as much as you might think — the artist may well be happy with a little reassurance, and to see you make an effort to address the issue they raised: nudging the vocal up or down a dB or so probably won’t make or break the production, but it might just be enough to make the singer feel more comfortable with the finished mix.

Either way, it’s worth mentioning that language can sometimes be a barrier when you’re trying to figure out what an artist means. Some of them tend to use somewhat vague terminology to express their thoughts, whereas you need a good understanding of their intention if you’re to act on it. For more on that side of things, check out my SOS March 2023 article, Understanding Client Feedback.

Assuming that your client feels positive about the mix, they may well still request some changes, and these are known in the trade as ‘revisions’. Obviously, you want to deliver something the client is happy with, and for them to feel some sense of ownership, but equally you don’t want a process that can drag you down an endless rabbit hole of changes and tinkering. To get the balance right, many engineers offer a finite number of ‘revision rounds’ for a given price or timescale, but others take a more relaxed ‘it’s done when it’s done’ approach. Personally, I lean towards a more informal arrangement. Often, I may just need to open a mix up, work through a short list of specific changes and everyone will be happy. But if the list of changes extends beyond three or four tweaks, I’ll probably suggest that we talk on the phone or get everyone into my studio to work through the issues. By the way, when making revisions for a client after a period of time, unless you notice something very obvious, try to resist doing more tweaks of your own — that can be a real temptation when hearing everything again with fresh ears!

Let It Go, Let it Go!

Hopefully, I’ve given you a few ideas about how you can start consistently pushing your mixes over the finish line, and I’ll leave you with one last thought. Learning to mix to a high standard takes years, but you’ll only improve if you work on a variety of material over that time and keep on finishing your mixes. There’s no point labouring away for a year on one track, chasing the perfect mix. Much better to do as well as you can now and finish the mix, even if you’re not quite satisfied with. Put it behind you, and move on to the next one. You’ll quickly learn that certain techniques will work wonders on one song but might do little for the next. Importantly, you’ll soon build up a body of work and draw confidence from seeing your own progress.

Why Try To Be Someone Else?

When using reference tracks, be sure to bear in mind Oscar Wilde’s advice!A common piece of advice is to use other engineers’ mixes as a reference while you push a mix towards the finish line, and it can certainly help — but only if you’re listening out for the right things! I find, for example, that it can flag up some common issues that I know I need to keep an eye (or rather ear) out for. Referencing might, for instance, draw my attention to an unpleasant build‑up in the 3‑4 kHz range that my ears have become used to after prolonged listening. It may make me notice that the kick or snare is sticking out just that bit too much, or that I’m over‑ or under‑doing the de‑essing. That sort of thing.

When using reference tracks, be sure to bear in mind Oscar Wilde’s advice!A common piece of advice is to use other engineers’ mixes as a reference while you push a mix towards the finish line, and it can certainly help — but only if you’re listening out for the right things! I find, for example, that it can flag up some common issues that I know I need to keep an eye (or rather ear) out for. Referencing might, for instance, draw my attention to an unpleasant build‑up in the 3‑4 kHz range that my ears have become used to after prolonged listening. It may make me notice that the kick or snare is sticking out just that bit too much, or that I’m over‑ or under‑doing the de‑essing. That sort of thing.

But what you should absolutely not be doing here is trying to make your track sound like the reference mix. Yes, you must obviously develop your technical skills, but arguably it’s what you personally bring to the table in terms of your ear, taste and judgement that is the most important aspect of mixing. As legendary engineer George Massenburg put it, “Comparison is the seed of discontent,” and if you start unpicking your mix or making lots of changes at this late stage, you’ll likely end up with a mix that lacks personality — it won’t sound like it’s yours or like the mix you’re referencing. In which case, what’s the point? So, take great care not to ‘lose yourself’ when you are comparing what you do to other people’s work. And just to hammer this point home, here’s Oscar Wilde’s advice: “Be yourself, everyone else is already taken.”