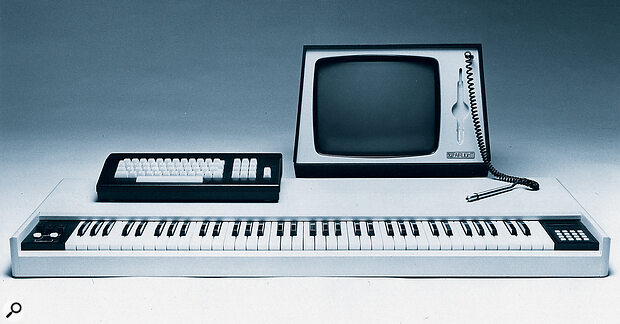

Fifteen years ago, computer music systems like the Fairlight CMI (above) cost as much as a decent‑sized house. Today, their capabilities are dwarfed even by standard desktop computers — but that extra power and complexity can make getting to grips with modern computer‑based music seem rather daunting.

Fifteen years ago, computer music systems like the Fairlight CMI (above) cost as much as a decent‑sized house. Today, their capabilities are dwarfed even by standard desktop computers — but that extra power and complexity can make getting to grips with modern computer‑based music seem rather daunting.

Paul Wiffen has been introducing people to digital audio on computers in one form or another for 10 years now, but sees people falling into the same old traps time and time again. In the first part of a short series he explains the importance of making the right decisions before you buy a new system.

It's not hard to see why computer‑based digital audio recording can seem so attractive. If you're still relying on analogue recording media with an absolute maximum of 24 tracks (but more likely eight or 16), the merest glance at a typical digital audio sequencer, with tens of super‑flexible audio tracks, virtual tracks, and a multitude of processing plug‑ins, is enough to send you racing for your sledgehammer and bawling for your piggy‑bank's blood. The attraction is even more understandable to high‑tech musicians who already have MIDI sequencing experience, as the same basic user interface is employed to carry out digital audio recording operations. For many, the whole concept appears irresistible.

As indeed it should! Digital audio recording on computers has clearly now passed its infancy, when only the moneyed few could play the game, and reached the stage where a modest outlay can bring you track counts and processing capabilities which would have the superstars of yesteryear taking an axe to their Synclaviers and Fairlight Series IIIs in outrage. However, as we all learnt at puberty, adolescence brings its own problems and a different situation to get used to.

When I first proposed the idea for this article to the editorial team at Sound On Sound, I was mainly concerned with getting across some fairly specific advice on setting up a computer‑based digital system, such as avoiding clicking by routing word clock correctly, striking a balance on CPU usage between track counts and signal processing, and so on (and for those who have already taken the plunge into digital audio, the second part of this feature next month will actually address some of these very important aspects of setting up a digital audio sequencing system around a computer). But thinking back to all the tortured souls I have spoken to on tech support phone lines or at trade shows who were reaching the end of their tether with computer‑based digital audio systems, the ones who were in the most impossible situations did not just have a misrouted word clock, or one too many plug‑ins running. Their problems ran much deeper in the choice of hardware and software and in their expectations of what such a system should do, and how quickly they should be able to achieve it. In fact, the more I thought about trying to help people deal with the transition to digital audio, the more I realised that the seeds of their happiness or sorrow are sown long before they have a hooked‑up system malfunctioning in some specific way. Time and time again I found myself thinking 'if only I'd been able to speak to that person before he bought anything, to find out what he was expecting to be able to do.'

Many of the actual problems these people were having have long since been solved, but the underlying misunderstandings and incompatibilities reoccur in new and more twisted forms. By stepping back from the immediate problems and looking at the general situation, however, I have been able to formulate some guidelines which should prevent new users from wading straight into quagmires where others have already floundered. Some of them may seem a little obtuse to start with, but bear with me and I think you'll save yourself a lot of time (and heartache!). So here goes...

You're Not In Kansas Anymore

The most important thing to remember at every point in the process of setting up and using a digital audio recording system based on a computer is that your central purchase is exactly that — a computer, not a musical instrument or recorder. It is a collection of components designed and optimised within an industry which has a completely different set of priorities to you. So if you ring up the mail‑order computer supplier (whose deal on a Pentium II 333kHz with a 9Gb hard drive and 24x CD‑ROM led you to buy from them) to tell them that your recordings are stuttering, don't be surprised if they have no interest in, or advice on, your problems.

When you buy a computer, you are not in the music industry any more (the Kansas in my heading). Just when you'd got used to all the pitfalls of buying a musical instrument to do what you need, suddenly you have deal with a completely different set of operational parameters. The fact of the matter is that you are probably going to have to learn a fair bit about computer technology, (probably no bad thing at the end of the twentieth century) and the way digital audio programs use it, before you can get the best out of your system. So how can you find the Yellow Brick Road that gets you back to Kansas, that lets you take this product of another industry and make it into something which facilitates your music instead of getting in the way?

You can reduce the amount you need to learn about general computing at the outset, by buying from someone who has not only heard of hard disk recording but can supply the entire system pre‑configured, including whatever software and hardware add‑ons like audio cards you decide you need (see September's PC Musician for more on specialist suppliers for music). You may end up paying more for your computer than if you buy it from that mail order company whose margins are so low they go out of business, but at least they might still be there when you need help (take it from a man who bought a PC from Escom two months before they went out of business!).

Another great tip is to talk to someone who is already doing what you want to do with a computer. They may not have ended up with the right system for you (and the last thing you should do is simply buy exactly what they have, especially if they have had it for more than three months), but there will be useful clues to help you get your ideal system together. Many computer‑using musicians have now formed their own networks of info and advice, using everything from the good old‑fashioned telephone to email and on‑line groups to help each other through the jungle of computer‑aided digital audio.

Get Your Priorities Right

The World Wide Web can prove an invaluable source of advice and contacts — just take a look at the SOS discussion forums..

The World Wide Web can prove an invaluable source of advice and contacts — just take a look at the SOS discussion forums..

Of course, there are some things you can do to reduce the risk of becoming a complete computer nerd who never actually gets around to recording anything. The first and most contentious of these is to make the decision which platform to go with for the right reasons. Here are just some of the more ridiculous reasons I have been given in the last year for their choice of platform by people with systems not delivering the performance they had hoped: "so I can get software free from the office/college/my mates," "I wanted to access the Internet and send email," "so that the kids can play games on it," and (my personal favourite) "because I wanted to publish the church newsletter on it as well." These people are storing up extra grief for themselves by increasing the risk that, having got the best level of operation they can from their music system, the next time they come back to it the installation of a game will have re‑plumbed their audio routings, or a DTP package will have tied up the printer port so that the MIDI interface doesn't work.

If you relegate music‑making to second or third priority when choosing your computer, don't be surprised if you don't get the best out of it for that application. The safest way to optimise your system for music is to use it for nothing else whatsoever. But back in the real world, you keep being tempted by a great‑looking alternative application, for which all you need is... a personal computer. The next thing you know, the central component of your recording studio is refusing to play ball, because of an extension or system conflict.

Now I am not comparing the musical use of a computer to a marriage, where any straying with other partners such as games, Internet access or desktop publishing is punished by divorce from the primary object of desire (although many a trial separation may well result). However, I can see a case for a computer equivalent of safe sex, where you take steps to protect your installation from the consequences of casual encounters with other applications. One of the ways of doing this was discussed in a recent SOS article on creating separate boot drives for different applications (see the PC Musician feature in SOS May 1998). There are many other techniques for "Safe Music Computing" which are not really within the scope of this article, but I would like to share with you the way I avoid the problem; multiple computers.

At any given point in time (in the last decade at least), I have had several computers in use, each of which has a different role. One of these will always be the main music computer, a second may be a sort of ancillary music machine, and another will be for my journalistic activities. Now 10 years ago, I would have been the first to be horrified at the idea that I would own several computers. But back then, I thought nothing of owning several synthesizers — and now the computer is a more fundamental component of my music‑making process than the synthesizer, so what's the difference? In fact, there are better reasons for buying a new computer regularly than a new synth. Once purchased, a great synth will always make the same great sounds (at least until it breaks down irreparably). The computer, on the other hand, plays a more fluid role in the music‑making process. One minute it might be chopping up a sample into little bits, the next recording a solo, the next running a DSP routine, whether an effect or a mixdown of several tracks. In fact, the number of things it may be doing is increasing all the time (the next task I plan to set it is physical modelling!). The more I ask computers to do, the more powerful they need to be.

The more I think about helping people with the transition to digital audio, the more I realise that the seeds of their happiness or sorrow are sown long before their hooked‑up system malfunctions in some specific way.

Planned Obsolescence

The technological progress of modern computing is proceeding at such a pace that last year's computer looks like an antique, and the one from five years ago a dinosaur. An article by Peter Warlock in October's MacWorld (published in the same position and fulfilling the same thought‑provoking function as Sounding Off in SOS) suggested that we no longer know what to do with all the power that is soon to be delivered in the form of 500MHz or even 1GHz clock speeds. Well, he's obviously never tried to do 32 tracks of hard disk recording with four bands of EQ per track and half a dozen plug‑in effects, let alone move up to 24‑bit recording! I'm here to tell you that whether or not mainstream computing will require next year's computers, I'm ready for them now (in fact, right now I could do with whatever the standard spec will be in 2001). Rest assured that once you embark on the headlong rush that recording digital audio on computers is becoming, you will feel the same. Each great new plug‑in that you get only increases your need for power, and so does increasing the sample resolution and rate of your recordings. Be prepared for pangs of covetousness at news items in computing magazines on machines with an extra 50MHz of clock speed.

"But hang on a minute", I hear you cry, "that means you have to get a new computer every year!" Indeed it does, or in my case, every 18 months at least (looking at the average time interval between new computers I have acquired over the last decade). Think about it — how much do you spend a year on musical equipment? In my case, it tends to be three or four grand (even after I've pulled every stunt possible to beg, steal or borrow what I need). So what I do is allocate half of that outlay to my 'Not enough CPU power' Fighting Fund. Instead of 10 years ago, when all the money was spent on discrete keyboards, effects units and recording devices, I now use half the annual budget (it sounds so planned, doesn't it? It isn't, believe me!) to upgrade the computer power.

This is how I rationalise it. In the '80s, I watched the likes of Geoff Downes and Stevie Wonder spend the equivalent of the gross national product of a small African nation on a Synclavier or Waveframe, only to be told a year later that, for the paltry sum of $50,000, it could be upgraded to the latest spec (stereo recording or eight tracks of hard disk playback or whatever it was at the time). In the '90s, I have watched producer friends upgrade their Digidesign system every 18 months to get more than four tracks per Pro Tools card, 24‑bit resolution or more powerful DSP Farm boards, and each time it has cost them more than my annual budget for music gear. So I still feel like I'm getting away with something to be putting only £1,500 into the latest, most powerful CPU every 18 months. Below is a potted list of the major arrivals (all of which cost between £1200‑1500 when I got them) in my computing career, complete with the must‑have application and hardware add‑on which forced my hand at the time (notice that every single one is a musical application!).

Given the paltry price your old computer system is likely to fetch second‑hand, wouldn't you be better off hanging on to it?Needless to say, by the time I buy a new machine, the current one is worth a fraction of what I paid for it. Believe it or not, I consider this a good thing. If it were worth a significant percentage of the cost of the new machine, I might be tempted to part‑exchange it or sell it privately, putting the proceeds towards the cost of the new machine. This is the biggest mistake you can make. There are much better uses for this machine than recouping a small proportion of your financial investment.

Given the paltry price your old computer system is likely to fetch second‑hand, wouldn't you be better off hanging on to it?Needless to say, by the time I buy a new machine, the current one is worth a fraction of what I paid for it. Believe it or not, I consider this a good thing. If it were worth a significant percentage of the cost of the new machine, I might be tempted to part‑exchange it or sell it privately, putting the proceeds towards the cost of the new machine. This is the biggest mistake you can make. There are much better uses for this machine than recouping a small proportion of your financial investment.

Firstly, it can continue to do the job it has been doing while I am getting the new machine broken in to the task. You wouldn't believe how often a new operating system throws up problems with a piece of hardware or software that works fine on the old machine — or how long it can take to get one platform to work as reliably as the other. For example, when I got the 8500/180 to run VST, it was three months before I got it working as well as Cubase Audio 16 on the Falcon MkII, and it took the addition of a digital audio card which was only released six months after that before I could send and receive eight separate channels via ADAT Optical to a digital mixer, something which had been a staple part of my working practices with the Falcon for over a year. Sometimes the new computer never manages to do everything I did with the old. Despite the fact that Steinberg very kindly gave me a free crossgrade to Cubase on the Mac when I got my Powerbook back in 1993, the MIDI timing never sounded as good as on the Falcon. So when some unprintable person at WOMAD stole my Opcode multiple output MIDI interface, I took this as a sign and got an SMPII for the Falcon. Even now, when the MIDI timing of a project is critical (or there are lots of MIDI tracks to run, which amounts to the same thing), I do all the sequencing on the Atari version of the software (and to judge by the interviews in SOS, so do quite a few other people), recording the result into VST on the G3 as digital audio.

The Atari ST is certainly long in the tooth, but if you're familiar with yours, you'll be able to work much more efficiently with it than you will at first with your new, super‑powerful Mac or PC.It is only when the new computer is doing everything I want it to do that I look at moving the previous one (or the one before that) into an alternative computing role which has nothing to do with music. As soon as I got the Mega 2, the Mac Plus went into the study to become the computer I wrote all my articles on. That lasted until the Powerbook was relieved from running Recycle by the 8500/180 and now I only run Microsoft Word and Quark Xpress on that. In contrast, the two PCs were only ever used for the GM‑compatible sounds of the Mediavision daughterboard and the Maestro 32 (I could never get used to the way Steinberg software runs on the PC), so as soon as I found ways to get the same sounds in the studio, they were moved out to the living room for more sensible PC usage such as games and CD‑ROM reading.

The Atari ST is certainly long in the tooth, but if you're familiar with yours, you'll be able to work much more efficiently with it than you will at first with your new, super‑powerful Mac or PC.It is only when the new computer is doing everything I want it to do that I look at moving the previous one (or the one before that) into an alternative computing role which has nothing to do with music. As soon as I got the Mega 2, the Mac Plus went into the study to become the computer I wrote all my articles on. That lasted until the Powerbook was relieved from running Recycle by the 8500/180 and now I only run Microsoft Word and Quark Xpress on that. In contrast, the two PCs were only ever used for the GM‑compatible sounds of the Mediavision daughterboard and the Maestro 32 (I could never get used to the way Steinberg software runs on the PC), so as soon as I found ways to get the same sounds in the studio, they were moved out to the living room for more sensible PC usage such as games and CD‑ROM reading.

I only ever get rid of a computer once everything it does has been replaced by a more recent machine. By that time, giving it away is about the only thing you can do with it, but it does put you on the good side of your relatives or employers, when you give them your computer hand‑me‑downs. I find it makes more sense to regard computers as a consumable or write their value off over three years, and use them in a secondary or recreational role, than try to get some money back from them when you move up to the next model.

This also solves the problem of the ever‑present temptation to use your main studio machine to play games on or scan pictures into (which is how I got onto this multiple computer topic in the first place): use the older machine instead and keep your main recording system untainted.

Buy Before You Need, Not When

This way of working applies even more to those of you thinking of moving to a computer system for digital audio for the first time. Whether you have a trusty cassette recorder, a multitrack analogue machine or something more recent like an ADAT, don't sell whatever system you have been using to record audio until you have the new computer system up and running (you may well be able to use the ADAT Lightpipe connections in a computer system as eight A/D and D/A converters, as I'll explain in Part 2). The same advice holds good if you have been using an Atari for sequencing MIDI: don't get rid of it until you are happy with the MIDI results your new digital audio computer setup is producing.

I have seen so many people end up tearing their hair out because they have part‑exchanged or sold their old system before their new machine was fully up and running, especially if they have done this on the eve of a brand‑new project which is supposed to be justifying the new purchase. All too often they end up with unhappy clients or fellow band members, or they miss a great career advancement opportunity because they couldn't achieve the simplest of tasks which took them no time at all on their old systems. Only phase out the old technology when the new stuff is doing the job properly, reliably and for a sustained period. In fact, I would say this maxim should be applied to everything in your studio (or even in your life), computer‑based or otherwise.

The best time to upgrade is when you have some free time to learn to use your new setup, or some non‑urgent projects which you can use to ease yourself into familiarity with the new system.

The Most Important Component — You

The other factor, of course, is that even if the system is working 100 percent (as it should from day one if you bought it from a digital audio dealer who is able to set it up properly!), there is still the fact that you aren't immediately going to be able to work at 100‑percent efficiency on a new system. By contrast, you have probably been using your old tape system or Atari for years, so that operating it has become second nature, not just in the physical manipulation of the controls but also in your comprehension of the way the system works. Don't expect any new system to feel like second nature for some considerable time. This is another reason why you should keep your previous system — so that if you need to do something quickly, you are not fighting your way through the project. I talk to people all the time who say "I used to be able to do this so quickly and easily on my old system; how come the new system takes so long/doesn't do it so easily?" Of course, sometimes there are some things which a new system cannot do as well as a previous system (which is why I never get rid of an old system until I am sure the new one replaces all the tasks I need to do), but more often than not, it is that the careless upgrader has not yet become accustomed to the new system and nothing is where they expect it to be. At the same time they are experiencing this frustration, they are comparing it with the level of unconscious operation they had got to with their previous system, where they didn't need to think of what to do, it just seemed to happen naturally.

You won't start to get the best of out your new system until you have trained yourself up to use it. So make sure that you have the time to learn the system before you have to use in earnest. The best time to upgrade is when you have some free time to learn to use your new setup, or some non‑urgent projects which you can use to ease yourself into familiarity with the new system. That is the best way to make sure that the promised improvement in working conditions and results is actually delivered within a reasonable timescale.

I hope that these thoughts give you some initial guidelines to follow when contemplating the thoroughly worthwhile move to digital audio sequencing, without incurring some of the grief I have seen others go through. Next month, we will get down to the nitty‑gritty of defining what you expect the system to do for you (having read all the great sales pitches out there) and spec'ing out the computer, the software and the hardware add‑ons that will fulfil your expectations. We will also look at some of the vital concepts you may be meeting for the first time like sample rate and word clock; a simple understanding of these can make all the difference between a great system and a living nightmare.

State Of The Art: Wiffen's Computers Through The Years

| COMPUTER |

YEAR |

MUST‑HAVE APPLICATION |

| Mac Plus w/40Mb HD |

1988 |

Sound Designer (I not II) |

| Atari Mega ST 2 |

1990 |

Cubase |

| Atari Falcon |

1991 |

4T/FX |

| 486/66/DX2 PC |

1992 |

Korg Mediavision daughterboard |

| Mac Powerbook 540C |

1993 |

Recycle |

| C‑Lab Falcon MkII |

1994 |

Cubase Audio 16 |

| Pentium 100 |

1995 |

Terratec Maestro 32 |

| Power Mac 8500/180 |

1996 |

Cubase VST |

| Power Mac G3/266 |

1998 |

Red ValveIt/VST 24 |