PART 2: Following on from last month's look at the advantages and pitfalls of analogue and digital tape, and hardware tapeless recorders, Paul White turns his attention to the ways in which computers can be used in audio recording. This is the second article in a five‑part series.

Computers have been part of mainstream studio equipment ever since Cubase and Creator first became available for the Atari ST, but it's only in recent years that they have become powerful enough, and hard disks cheap enough, to make audio multitracking on a PC or Mac both practical and affordable. I'm not going to touch on the Mac‑versus‑PC argument in this article, but rather consider the merits or otherwise of entrusting audio to any type of computer. The ability to integrate and control everything in a single environment is very attractive, as is the facility to cut and paste audio information in the same way as MIDI data, but what about the horror stories — the hardware incompatibilities, the timing problems, the crashes, clicks and buzzes? And even if everything works perfectly, will the computer do everything a tape‑based system did? More importantly, will it do it without interrupting the musical process?

Audio With Computer's Own Hardware

Perhaps the biggest growth area in contemporary recording is music on computers. Most of us use computers as MIDI sequencers, but the majority of sequencers now also include audio support that relies entirely on the host computer's processing power. PC users will need to fit an audio card to get sound into and out of the computer, whereas Mac users have the advantage of the 16‑bit stereo analogue I/O built as standard features into all the latest Macs.

<!‑‑image‑>Computers have grown significantly more powerful in terms of both speed and processing power over the past two years, while RAM prices have fallen to less than 10% of what they used to be. This has allowed software designers to use some of the additional processing power to provide real‑time effects and mixing, so that in theory you can have 90% of your studio entirely inside the computer, including perhaps one or more MIDI sound sources. Given enough processing power, you can even throw in software synthesis!

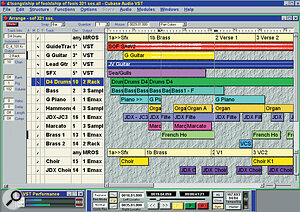

So‑called 'MIDI + Audio' software packages like Cubase VST and Logic Audio provide MIDI sequencing, multitrack recording, digital mixing with EQ, plus bundled and third‑party software effects plug‑ins. Recording is limited to no more than two channels of audio at a time on a Power Macintosh, and the same for a PC fitted with a basic stereo‑in, stereo‑out soundcard. Because the effects, processing and mixing are all internal, having only stereo outputs may not be a problem, but whether or not you can live with recording only two channels at a time depends on your requirements.

You can see why this approach is so attractive — it's cheap, it sits on a single desktop and it offers advanced features such as automated mixing, graphical editing of audio files, and manipulation of audio tracks using the same familiar tools with which you manipulate MIDI tracks. However, those who've used such systems will know that it's not all plain sailing.

To start with, you need the most powerful computer you can get your hands on if you're not to run out of horsepower when patching in virtual effects and processors. There'll always be a limit on what your computer can do, but on slower machines, that limit is reached very quickly. In a hardware‑based studio, all the processors are always available for use but in the virtual world, effects and processors only exist so long as there is sufficient computing power to run them.

<!‑‑image‑>Assuming you have a fast machine, what other problems can you expect? Firstly, unless you buy a MIDI control surface with physical faders, you're going to have to do all your mixing on‑screen using the mouse. You can automate the mix and keep tweaking it until it sounds right, but it's still a lot more tedious than using a hardware mixer. If this doesn't worry you, ask yourself whether you can live with the physical noise of a computer and a fast hard drive. As computers get faster, the processors run hotter and the cooling fans have to be stronger. The result sounds like an amplified fan heater, which is an unwelcome intrusion both when recording and mixing.

Maybe you're happy with all of these potential drawbacks; but now we come on to reliability. Firstly, you'll have to back up data when the hard drive is full, so you need to buy a removable media drive. What's more, even computers that are set up as well as possible will occasionally throw a fit, so if you're working in a commercial or time‑sensitive environment, ask yourself whether you can survive a major system crash, which may or may not involve data being permanently lost. Even if your system works fine one day, you may find that the simple act of loading a new piece of software or updating an old one can throw the system into a fit that takes several guru‑hours to fix. Even the best‑written software has some bugs lurking in the background, waiting to spoil your day. Indeed, you may be one of the unlucky ones who never gets their system to work properly in the first place!

We receive many calls from users whose audio sequencer tracks drift out of time with each other, whose soundcards refuse to talk to their software, whose hard drives (or graphics cards) cause ticking on the audio outputs, or who experience unacceptable delays when playing back audio tracks. The only advice we can give is to buy your computer from one vendor as a complete system, and don't use it for any purpose other than music. If you don't follow this rule, don't be surprised if nobody will help you out — each individual component will probably check out fine, and it's only when you put them together that you get problems. Also, if you're one of those people who can't resist installing and running games or, worse still, those dubious bits of software that come on magazine cover disks, you might as well sign up for the computer‑guru night classes now; you'll need them!

The quality of recordings made using only integral hardware depends largely on the quality of the analogue‑to‑digital and digital‑to‑analogue converters used, but as a rule these are unlikely to be as quiet as good outboard converters simply because they're inside the computer. The best audio cards seem to offer a signal‑to‑noise ratio of about 90dB, while the worst provide less than 60dB (though the manufacturers' figures don't always relate to the performance of their card in your specific computer). You'll need a good mic amp or voice channel to get a quality signal into the system, and if you use external MIDI modules, you'll still need a hardware mixer to combine the outputfrom the computer with the outputs from your MIDI modules. What's more, because the inside of the computer is essentially a closed system, you'll be extremely limited in patching in any of your hardware effects and processors.<!‑‑image‑>

Computers + Multi‑Channel Cards & Interfaces

Emagic's Audiowerk8 multi‑channel PCI card.

Emagic's Audiowerk8 multi‑channel PCI card.

The type of system described above can be made much more flexible by adding a multi‑channel soundcard. The cheaper of these have the A‑D and D‑A converters on the board itself, while the more upmarket models may put the converters in an external box so as to give better signal‑to‑noise performance. Most low‑cost multi‑channel cards, such as Emagic's Audiowerk8, have fewer inputs than outputs and are therefore most suitable for people who record by overdubbing one or two parts at a time. If you spend a little more on something like Event's Layla, you can have eight inputs that allow you to record several tracks in one take.

The main advantage of multiple outputs is that you can feed your tracks to separate channels in an external mixer, and this in turn means that you can use your hardware effects and processors more effectively. Indeed, your computer now operates more like a multitrack tape machine as far as the rest of your system is concerned. However, you don't have to use all the outputs to carry separate tracks — a program that provides mixing within the computer may let you configure some of the outputs as track or mix outputs and the others as effects sends, in which case you could use a much simpler external mixer and still be able to patch in your hardware effects units. Whether or not you can do this depends on the choice of card and software.

Audio On Computer With Extra DSP Assistance

The Digidesign Pro Tools System.

The Digidesign Pro Tools System.

The next step up from running a system in which the computer's own CPU does all the work is to give it some assistance in the form of plug‑in DSP cards, as in Digidesign's Pro Tools system, or external hard disk recording hardware such as the Yamaha CBX D5. Newer systems include the Ensoniq PARIS, and there are other well‑established players such as the Soundscape SSHDR1 and SADiE. Prices can vary enormously, and the better systems may cost considerably more than the computer into which you plug them — but for work where you need a lot of tracks and a lot of real‑time processing, this is the way to go.

I'll use Digidesign's Pro Tools system as an example, because it has been around for a long time and enjoys good third‑party support both from sequencer manufacturers and from the third‑party software developers who design plug‑in effects and processors. Here, the hard work is done by multiple DSP chips located on PCI cards plugged into the computer, and to ensure optimum audio quality the multi‑channel audio interfaces are outside the computer in a separate rack box. The DSP chips handle mixing, EQ and plug‑in effects, and there's also circuitry dedicated to looking after the transfer of audio to and from hard disk. This takes a load off the computer's mind and generally makes for a more stable, more powerful system.

<!‑‑image‑>Another advantage of these systems is that if at any point you need to run more software plug‑ins, some of them (Pro Tools included) will allow you to add further DSP cards. Pro Tools also has its own internal bussing system known as TDM, which allows audio signals to be routed in many different ways, and it's via TDM that third‑party plug‑ins are accommodated.

Summary

At SOS, we are frequently asked about what is the best type of recording system to buy. As you can see from this series, there is simply no such thing, because every approach has its own set of strengths and weaknesses. Computers are incredibly flexible and offer a lot of functionality for relatively little money, but they can be very temperamental, they make a lot of physical noise, and both the hardware and software evolves at a frightening rate.

Modular digital multitrack tape (see last month's instalment) offers good compatibility with other studios, and the media cost is cheap, but there's no random access and locking two or more machines together is, to be honest, pretty tedious. All‑in‑one digital multitrackers (also dealt with last month) have their appeal, but the mixer may not be big enough to handle all your other sound sources, and if the mixer section is digital, you'll probably find that it offers only limited possibilities for plugging in your own analogue processors, or more than one digital effects unit (this is a problem shared by many stand‑alone digital mixers).

Analogue tape is reliable and has a musical sound, but it deteriorates gradually with use, so you might find that you've lost a little top end by the time you've finished a project. What's more, on semi‑pro machines, the noise reduction can affect the sound quality quite noticeably, and of course there's no random access facility, nor any way to copy a tape or a section of tape without incurring some quality loss. However, sudden and total data loss is unlikely unless the dog eats your master tape.

Ultimately, the right choice is determined by the job you want to do, your budget, how prepared you are to learn something different, and whether you can afford the time to make backups if the system you choose has a fixed hard drive. Everybody has a different way of working and a different set of needs, but hopefully this short series will help point you in the right direction.

Audio With Computer's Own Hardware

benefits

- Lots of features in one integrated package.

- Affordable.

- Takes up relatively little space.

- Integrates MIDI, audio and mixing in one environment.

- New software updates bring new features.

- Wiring is kept to a minimum.

disadvantages

- Powerful computers are needed to run multiple effects, processors and mixing alongside audio recording and MIDI sequencing.

- Some form of data backup system (or fast removable‑media drive) is necessary.

- New software upgrades may not run on your existing machine, so computers have to be upgraded periodically.

- Computers are physically noisy, while monitors can interfere with electric guitars and basses.

- Patching in hardware effects and processors is awkward or impossible.

- System crashes and hardware compatibility problems can be extremely difficult to sort out.

- The best software packages have a steep learning curve.

- Unless you buy additional hardware, everything has to be controlled from the keyboard and mouse.

- Computers don't always handle manual punching in and out as well as a tape machine or dedicated hardware recorder.

- Can be difficult to transfer project data from one studio to another.

Audio On Computer With Extra DSP Assistance

benefits

- More processing power available for mixing and high quality real‑time effects.

- Ability to run DSP‑specific or more processor‑intensive software that won't run on standard computers.

- More sophisticated systems may be able to handle more audio tracks than an 'integral hardware only' system.

disadvantages

- Cost likely to be significantly higher than for an audio interface‑type soundcard.

- Some systems use multiple cards, which may require more slots than you have available in your computer.

- If the software that you run on the new hardware was specifically developed for it, you might be restricted in your choice of software in the future.

Computers + Multi‑Channel Cards & Interfaces

benefits

- You're not restricted to using just the internal software mixer and effects (where provided), so your working methods can be far more flexible. This single advantage outweighs all the disadvantages.

- You can sometimes use simpler software that doesn't include mixing or virtual effects, and that in turn places fewer demands on your computer.

disadvantages

- All the above‑mentioned disadvantages of recording on a computer, plus...

- You have to budget for an external mixer (and probably some hardware effects processors), though if you use any sequenced instruments, you're probably going to need a separate mixer anyway.

- Multi‑channel soundcards cost more than simple stereo‑in, stereo‑out devices.

- There's more wiring to sort out.

- You may find that your choice of sequencing software is not supported by all multi‑channel soundcards.