By the 1940s, however, recording studio engineers began experimenting with artificial reverberation through repurposing bathrooms, basements and storage rooms. These makeshift chambers used a speaker to emit sound and a microphone to capture the resulting effect, which was then blended into the original recording.

By the 1940s, however, recording studio engineers began experimenting with artificial reverberation through repurposing bathrooms, basements and storage rooms. These makeshift chambers used a speaker to emit sound and a microphone to capture the resulting effect, which was then blended into the original recording.

Before plates and springs, the great studios of the ’50s and ’60s created magical ambiences through a mix of science and inspired guesswork.

In an age where we can drop a reverb plug‑in onto a track in seconds, it’s easy to forget that adding space and depth to a recording was once a serious technical challenge. Long before plates, springs and digital algorithms, the earliest pioneers of artificial reverb relied on real architecture — and a fair bit of trial and error.

The origins of acoustic chambers lie in radio. Back in the early ’20s, and well before their adoption in music recording, major American networks such as NBC, CBS and Mutual had built chambers to create dramatic effects for their radio shows. By the 1940s, however, recording studio engineers began experimenting with artificial reverberation through repurposing bathrooms, basements and storage rooms. These makeshift chambers used a speaker to emit sound and a microphone to capture the resulting effect, which was then blended into the original recording. Later, rooms were designed with cement‑plastered, non‑parallel walls, and non‑parallel floors and ceilings, to achieve a more prolonged and smoother sound decay.

Bill Putnam Sr (right) with Nat King Cole.Photo: Universal Audio

Bill Putnam Sr (right) with Nat King Cole.Photo: Universal Audio

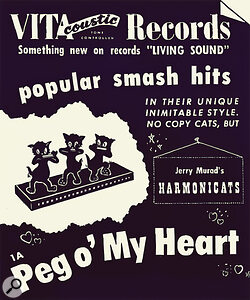

Vital Signs

Milton T ‘Bill’ Putnam Sr was one of the first to refine the approach. At Universal Recording in Chicago, he turned the studio washroom into a source of artificial reverb for the Harmonicats’ ‘Peg O’ My Heart’. This innovative technique contributed significantly to the record’s unique sonic texture. The single was released through Putnam’s short‑lived but influential Vitacoustic label — a name deliberately chosen to reflect the company’s identity as a purveyor of “living sound”, with echo effects central to the label’s aesthetic. An article published in Billboard in 1947 introduced the launch of Vitacoustic and described Universal Recording’s new “third‑dimensional” sound. According to the piece, Putnam’s method created an immersive audio experience, likening it to the ambient effect of a well‑designed restaurant sound system with multiple strategically placed speakers. This report stands among the earliest documented mentions of artificial reverberation being used deliberately to enhance the sense of depth and realism on record.

Billboard, May 10, 1947.Art Sheridan, who witnessed these sessions first‑hand, later recalled that Putnam and engineer Bernie Clapper constructed the original echo chamber setup by placing a speaker and microphone in the adjacent women’s washroom. “It was that old‑style tiled kind of space — it had great resonance,” he said. To prevent interruptions during takes, they even stationed someone at the door to stop anyone from entering and flushing the toilet mid‑session. The resulting effect gave ‘Peg O’ My Heart’ a spacious and distinctive quality that resonated with listeners. The record climbed to number one in 1947, selling an impressive 1.4 million copies and putting Universal Recording Corp firmly on the map.

Billboard, May 10, 1947.Art Sheridan, who witnessed these sessions first‑hand, later recalled that Putnam and engineer Bernie Clapper constructed the original echo chamber setup by placing a speaker and microphone in the adjacent women’s washroom. “It was that old‑style tiled kind of space — it had great resonance,” he said. To prevent interruptions during takes, they even stationed someone at the door to stop anyone from entering and flushing the toilet mid‑session. The resulting effect gave ‘Peg O’ My Heart’ a spacious and distinctive quality that resonated with listeners. The record climbed to number one in 1947, selling an impressive 1.4 million copies and putting Universal Recording Corp firmly on the map.

Early studio experimentation by both Bill Putnam Sr and Les Paul with artificial reverberation would prove instrumental, eventually leading to more sophisticated and permanent designs that became standard in recording studios throughout the following decade. By the mid‑1950s, a handful of studios had begun treating recorded sound not simply as a document of performance, but as raw material for constructing entirely new sonic environments. The golden age of the acoustic chamber was brief — roughly from 1956 to 1958 — but in that time, some of the most iconic chambers in history were designed and installed. Alongside the rise of multitrack tape and sound‑on‑sound overdubbing, they laid the foundation for a new kind of music production based around not merely capturing sound, but creating it.

Columbia Calling

While Putnam was pushing technical boundaries in Chicago, across the country in New York, Columbia Records’ CBS 30th Street Studio was shaping what would become one of the most revered natural acoustic environments in recording history. The studio’s distinctive sound stemmed from its architectural features, including 50‑foot ceilings and unvarnished wood floors. The natural acoustics of the space created a rich, resonant sound that couldn’t easily be replicated and which contributed significantly to the studio’s legendary status. Columbia engineers Frank Laico, Stan Tonkel and Fred Plaut earned a reputation for their innovative use of natural room ambience and echo.

During World War II, Frank Laico had worked on the top‑secret voice encryption system SIGSALY, developed at Bell Laboratories, which gave him early experience with complex audio technology. His status as an innovator at Columbia was firmly established when he and head of A&R Mitch Miller repurposed a small, concrete store room in the basement. “It was all concrete,” Laico recalled. “We got rid of the garbage that was in there and experimented.” The duo tried various microphone and speaker setups until they found something that worked. Once Miller was satisfied, “That’s the way we left it — and we never changed it.”

Frank Laico at CBS 30th Street.Photo: by Jim Reeves, Reeves Audio

Frank Laico at CBS 30th Street.Photo: by Jim Reeves, Reeves Audio

By installing a speaker and a Neumann U47 microphone, they transformed the space into one of the most renowned acoustic chambers in recording history. As Laico explained: “The room itself had its own echo, which was very nice. However, it would produce a different‑sounding echo with every session that came in. With the chamber, we could regulate the echo by adjusting the volume of each instrument. Every mic had its own send, so we could set its level, and we could also regulate the return.”

To enhance the reverberation, Laico pre‑delayed the signal before it reached the chamber by running the sound through a tape machine at 15 inches per second, adding subtle separation and extra depth to the effect.

To enhance the reverberation, Laico pre‑delayed the signal before it reached the chamber by running the sound through a tape machine at 15 inches per second, adding subtle separation and extra depth to the effect. Laico credited Les Paul for the idea. “Les told me how he smoothed things out by...

You are reading one of the locked Subscribers-only articles from our latest 5 issues.

You've read 30% of this article for FREE, so to continue reading...

- ✅ Log in - if you have a Digital Subscription you bought from SoundOnSound.com

- ⬇️ Buy & Download this Single Article in PDF format £0.83 GBP$1.49 USD

For less than the price of a coffee, buy now and immediately download to your computer, tablet or mobile. - ⬇️ ⬇️ ⬇️ Buy & Download the FULL ISSUE PDF

Our 'full SOS magazine' for smartphone/tablet/computer. More info... - 📲 Buy a DIGITAL subscription (or 📖 📲 Print + Digital sub)

Instantly unlock ALL Premium web articles! We often release online-only content.

Visit our ShopStore.