The finished installation: you can see the GK‑5 pickup near the bridge, and the TRS data socket fitted to the side of the guitar. The electronics and woodwork are hidden behind the scratchplate.

The finished installation: you can see the GK‑5 pickup near the bridge, and the TRS data socket fitted to the side of the guitar. The electronics and woodwork are hidden behind the scratchplate.

There can be advantages in permanently installing the pickup for your Roland/Boss guitar synth or modeller. Usually, it’s a job for a luthier, but with some basic woodworking skills you can go the DIY route...

Over the past few decades, Roland (more recently under the Boss name) have released a number of GK‑series ‘divided pickups’ for driving their guitar synths and guitar modellers, with the GK pickups delivering the separate signal from each string that these devices need in order to function.

GK‑5 Essentials

The most recent incarnation, the GK‑5, is available for guitars with six or seven strings and basses with up to six strings. As regular readers will know from my Boss VG‑800 review in SOS March 25, the standard version can be fitted to most guitars without modification. This pickup differs from the earlier 13‑pin GK systems, in that it now uses a quarter‑inch TRS jack data connection rather than a 13‑pin DIN connector, and the signal is now digital whereas before it was analogue. This new Serial GK digital interface is compatible with the latest Boss guitar synth (GM‑800) and modeller (VG‑800) but, courtesy of an adaptor box (the GKC‑DA GK Converter) it can also control older 13‑pin devices. Another box, the Boss GKC‑AD GK Converter, allows earlier analogue divided pickups like the GK‑3, GK‑2A and GK‑2 to be used with the most recent synths and modellers.

The full kit. As the wires are terminated with connectors, there’s actually very little soldering required.

The full kit. As the wires are terminated with connectors, there’s actually very little soldering required.

The small connector box, which can be fitted to the guitar body using adhesive pads, or using a clamp arrangement that sits around the strap button, has no physical controls. The earlier GK control boxes have a volume control, a GK/Guitar/Both switch, and buttons for moving up or down through the presets. In practical terms, the lack of such facilities on the new version means using an expression pedal to control the volume of the connected device. The GK‑2, GK‑2A and GK‑3 also had an input for a standard guitar signal, so that it could be sent to the receiving device without needing a second cable, which you do with the latest version.

While the standard GK‑5 provides a practical way to equip a guitar for driving compatible Boss devices, not everyone likes the exposed connector box and the loop of cable linking it to the pickup. It is admittedly tidier than the older GK‑2, GK‑2A, and GK‑3 systems, but at the expense of losing physical controls and the ability to feed the regular guitar sound down the same cable. However, there is another option, in the form of the GK‑5 KIT, a version that’s intended for more permanent installations and which brings back the missing control and connectivity options.

If you want to use a GK pickup on a valuable guitar, I’d strongly suggest that you stick with the standard GK pickup and use the adhesive mounting pads...

KIT & Caboodle

Although the original guitar’s circuitry remains intact, meaning its usual output is not affected, installing the GK‑5 KIT invariably requires modification of the guitar, because all the new electronics are hidden away inside the guitar body. The extent of the modifications depends on the guitar’s existing body construction and control layout, and fitting a GK‑5 KIT would normally be undertaken by a luthier. But as I’m no stranger to DIY, I thought I’d see just how easy it would be to fit one myself. I chose to add it to one of my DIY S‑type guitars, and it’s worth noting that I was happy to experiment on this one — if you want to use a GK pickup on a valuable guitar, I’d strongly suggest that you stick with the standard GK pickup and use the adhesive mounting pads for the connector box and pickup, since permanent mods of the sort described below will affect the resale value!

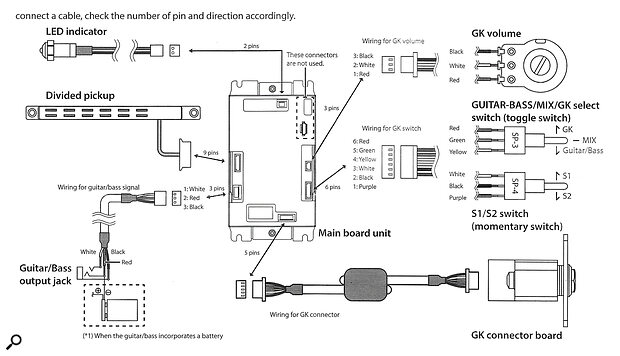

The GK‑5 KIT comes with a clear diagram to show you how to hook everything up.

The GK‑5 KIT comes with a clear diagram to show you how to hook everything up.

The GK‑5 KIT comprises the GK‑5 pickup itself, some circuitry inside a low‑profile metal case, all the necessary cables, a volume pot, a power LED, a couple of switches, and the output jack assembly. By way of instruction, there’s a very clear diagram that shows where things plug in and how to wire the switches. Helpfully, all the included cables are colour‑coded and terminated in mini connectors that plug straight into the circuit box, which means that the only soldering required is for the switches, the volume pot and the cable that links to the regular guitar output. However, where to site the circuitry within your guitar is up to you. A common approach is to create a cavity in the back of the guitar, with the pot and switches fitted to the pick guard (as with a Strat) or fitted within the control cavity of an instrument that accesses the controls from the back (as with most Gibson models). The switches are small and the volume pot could replace one of your existing tone pots if there’s no space to add an extra control.

Marking out the outline of the pieces to be installed, to establish the size and location of the cavity and holes that will be required.

Marking out the outline of the pieces to be installed, to establish the size and location of the cavity and holes that will be required.

After some deliberation, I decided to see if I could fit everything to the back of my guitar’s pick guard, and it turned out that there was just enough room to fix the circuit box, allowing a couple of millimetres clearance at the neck end of the pick guard. To make this fit, though, I’d have to create a cavity around 18mm deep under the pick guard, and this would have to come to within a millimetre or two of the end of the pick guard, so precision would be required. So that I knew where it would be OK to remove wood without it being visible, I started by removing the pick guard, putting masking tape on the guitar body, and then replacing the pick guard so I could draw round it.

I wouldn’t recommend using a hammer and chisel to remove the wood! The ideal tool is a hand router, fitted with a template‑following cutter — that’s a cutter with a bearing at the router end of the shaft that follows a template to allow precise cutting. These needn’t be expensive, but a guitar is perhaps not the best first project, and if you aren’t handy with a router, I’d suggest you make contact with one of the local woodworking clubs and see if you can talk somebody into doing it for you in exchange for a small donation.

Template Trick

The MDF template used for routing the straight edges. Note the drilled hole at the top left, as a starting point for the router.To create the template I simply used three straight strips of MDF, but anything solid and around 6mm thick will do the job. The trick is to fix this firmly to the body in such a way that it can still be removed when you’re done cutting, and a common way of doing this is to put masking tape on the guitar body and then another layer on the back of the template strips. You then stick the masking tape back‑to‑back using a few drops of superglue. Once the superglue has solidified, the bond is very strong but you can still peel all the tape away from the body when you are finished.

The MDF template used for routing the straight edges. Note the drilled hole at the top left, as a starting point for the router.To create the template I simply used three straight strips of MDF, but anything solid and around 6mm thick will do the job. The trick is to fix this firmly to the body in such a way that it can still be removed when you’re done cutting, and a common way of doing this is to put masking tape on the guitar body and then another layer on the back of the template strips. You then stick the masking tape back‑to‑back using a few drops of superglue. Once the superglue has solidified, the bond is very strong but you can still peel all the tape away from the body when you are finished.

As router cutters are, by nature, circular (I used a 10mm cutter), it can help to first drill a hole in the corners of your marked aperture, so that you can use a chisel or sharp knife after routing to make the corners more square. As long as you make sure the bearing is running along the sides of your template strips, the cut should be perfectly clean. It isn’t wise to try to remove too much wood in one go, so I used two cutters of different lengths. If you can attach a vacuum clear to the dust port on the router, then cutting will be easier and there will be less in the way of wood dust floating around. I know this sounds scary but as long as you take your time it is actually very straightforward, and if you decide that a rear cavity is the way to go, you can use the same tape and MDF strip style arrangement to create your cavity template, after which you will need to drill one or more holes linking it to the usual control cavity to accommodate the wires for the pot and switches. A plastic cover made from pick guard material can be used to cover the cavity.

Having got that part of the job out of the way without incident, I now had to make a hole in the side of the guitar body to accommodate the output jack, which comes with a small circuit board attached (carrying a small connector for the included cable). The kit also includes a plastic jack plate, but to allow the socket to fit along with its little circuit board, the hole you drill needs to almost as wide as the plastic plate. To err on the safe side, I used a 22mm spade bit in my pillar drill and then used a wood rasp to shape the hole so that the socket assembly would fit. It was then easy enough to drill a hole linking it to the main control cavity.

The newly routed cavity and hole for the jack socket.

The newly routed cavity and hole for the jack socket.

That leaves just one more bit of woodwork to do, and that’s to remove a small amount of wood beneath the location of the divided pickup, to allow its cable a path into the control cavity. The pick guard also needs to have a slot cut in it to allow the cable from the pickup to pass through. The pickup mounts to the rear edge of the pick guard, close to the bridge, and height adjustment can be done either by packing thin strips of neoprene foam under it or by using height adjustment springs. As the amount of adjustment needed on an S‑type guitar is usually only a couple of millimetres, there’s no space for the springs between the pickup and pick guard but it is possible to use them by drilling a hole (just a little larger in diameter than the spring) through the pick guard and into the wood, around 10mm or so deep. The spring will then sit in the hole giving it room to compress fully as the pickup mounting screws are tightened.

Rather than try to find space for yet another control pot, I rewired the (middle) tone pot to act as a global tone control, and then replaced the other tone control with the volume knob for the GK‑5. There was plenty of space for the switches and LED, so I just placed these where they wouldn’t get in the way when I used the guitar’s volume control. Drilling pick guard plastic is very easy after all that woodwork!

Finishing Off

For my installation, I decided to fix the circuitry box to the back of my pick guard using double‑sided adhesive tape. One benefit of this approach is that the majority of the wiring is then confined to the pick guard, and once all the connections have been plugged in, it’s a simple matter to tidy up the wiring using thin cable ties. The only cable I found a little tricky was the one that links the circuitry box to the output jack because it isn’t very long, it is screened (making it stiffer), and it has a ferrite filter in the middle. But, if you plug this into the connector box end just before fitting the pick guard to the guitar, there’s enough slack to do the job (providing you haven’t placed the jack assembly too far from the circuitry box).

Once I’d wrestled the pick guard assembly back into place, I screwed down the pickup and made the necessary action and pickup height adjustments before testing. If you have a guitar that has insufficient space beneath the strings for the pickup, this can be fixed by putting a thin wood or plastic shim (a strip of old credit card or even thinner should be enough) at the back of the neck pocket, just to lift the end of the neck. This will allow you to raise the bridge saddles so that the GK pickup will fit comfortably beneath the strings.

All the components wired in place on the pick guard, ready to fit to the guitar. The finished result is in the main picture at the top of this article.

All the components wired in place on the pick guard, ready to fit to the guitar. The finished result is in the main picture at the top of this article.

I plugged my guitar into the VG‑800, the blue LED came on and everything worked! For the pot and switches to work, it’s necessary to go to the GK setup page in the connected device and select the pickup type as 'GK‑5 KIT'. The centre‑sprung toggle then moves through patches and the three‑way toggle selects GK/Guitar/Both.

Admittedly, this project is not for the faint‑hearted, but a lot of guitar players do their own modifications, and may well have the skills to do this kind of work — at the end of the day, it boils down to some simple soldering and the ability to use a router safely. Soldering’s easy enough to learn, and if you’re unsure about the routing, then just a little assistance from someone used to woodworking tools should be enough to get the job finished.