Greg Price has spent nearly 20 years at front of house for some of the biggest names in rock, and now his company believe they’ve perfected the art of live recordings.

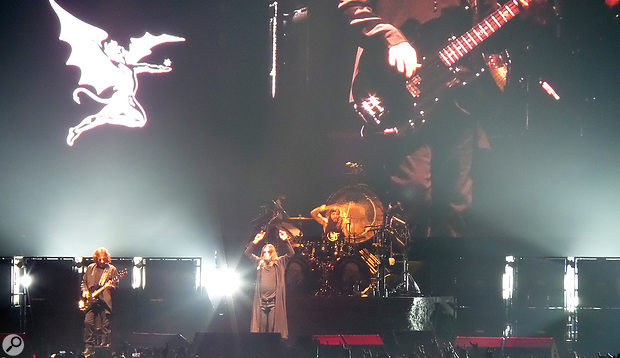

Over the course of the last 40 years, Greg Price has firmly established himself as one of the world’s leading front-of-house engineers, while the live recordings his company Diablo Digital have been involved with have turned heads aplenty. The Rolling Stones, U2, Fleetwood Mac, Justin Timberlake, Jay-Z, Rush and Black Sabbath — with whom Greg has been associated since 1997 — are just a few of the mammoth acts that Price and his business partner Brad Madix (FOH for Rush) have helped capture in concert since they first established the joint venture in 2013.

Diablo Digital build and market turnkey recording systems for use by FOH engineers and artists right across every level of the music industry, and they are proving a force to be reckoned with. Black Sabbath’s 2013 CD/DVD box set Live... Gathered in Their Masses is a case in point. Recorded and mixed by Greg in 5.1, the release has garnered significant critical acclaim and has been lauded by many as being the definitive Black Sabbath live recording. In addition, Brad Madix recorded Rush’s similarly celebrated 2013 Clockwork Angels Tour live DVD, using two 128-track Sonnet Echo Express III-R machines.

As a live-sound engineer, Greg Price has worked with some of the biggest rock bands around. In addition to Ozzy Osbourne and Black Sabbath, Greg has mixed everyone from Kiss, Chicago, Aerosmith and Van Halen right through to Rage Against The Machine, Limp Bizkit, Velvet Revolver and Foo Fighters. Price also spent a very memorable eight years with Glen Campbell in the 1980s and even earned a few pop stripes a decade ago when he engineered for Hannah Montana (aka Miley Cyrus), Christina Aguilera and the Cheetah Girls.

But, while Greg enjoys mixing and recording all artists and genres, there is — and always will be — one particular act who will never cease being priority number one.

“I always tell people, ‘I don’t mind working for you but, as soon as Ozzy needs me, I’m going back to work for him!’” laughs Greg, as we catch him on a rare day off during Van Halen’s North American tour. “Because he’s my favourite, and it’s not because of money or anything, it’s because of my relationship with those people. Some people say, ‘Greg, you’re still mixing Ozzy and Black Sabbath after 20 years? What’s wrong with you?’ And I say, ‘I love it, I love him and I love their music — that’s good enough for me, OK?’”

The Price Is Right

Greg’s younger brother Steve Price is the drummer in San Francisco pop rock band Pablo Cruise, who formed in 1973. The older Price sibling still remembers vividly the day in 1975 that his whole world changed forever. This lightbulb moment served to mark the very beginning of his life journey as a sound engineer.

“I was living in LA and Pablo Cruise came to LA to make a record with Val Garay at The Sound Factory in Hollywood,” he recalls. “My brother invited me down there and the moment I walked into the recording studio and saw Val and Greg Ladanyi behind the console, I said to my brother, ‘That’s what I’ve got to do!’ and [Pablo Cruise] hired me. I could drive a truck and I played guitar so I knew how to set up guitars, and I started as a simple roadie. I would drive the truck and be an equipment guy on tour for Pablo Cruise, but then, when they went into the studio, I went into the studio with them. I started from the very beginning, making headphone mixes and putting up microphones, and then I began as an intern at the Record Plant. I worked with two amazing engineers during that time. My first internship was with Bill Schnee. He was amazing and he taught me how to engineer. Then I worked with Tom Dowd and he taught me how to produce So, really, Pablo Cruise gave me my start in the business. I leant the fundamentals from Tom Dowd and Bill Schnee — basic things such as gain structure, microphone placement and how important different microphones are.”

Some of those key engineering and production ‘gifts’ from both Bill Schnee (Steely Dan, Neil Diamond, Marvin Gaye, Rod Stewart) and Tom Dowd (Ray Charles, Bobby Darin, Eric Clapton, Aretha Franklin) have certainly helped shape Greg Price’s approach to engineering, both on stage and in the studio.

“Tom Dowd taught me everything about that R&B style of recording and mixing,” explains Greg. “He used to call me ‘kid’ and one day we were going to do a vocal. I got up this [Neumann] U47 tube with the pop shield and he walks in and goes, ‘Kid, what are you doing?’ I’d gone out and got the most expensive Neumann mic and Tom goes, ‘Kid, do you know what I recorded ‘Respect’ [by Aretha Franklin, 1967] on?’ I go, ‘No, what?’ He goes, ‘It was an [Electro-Voice] RE-15!’ Not even an RE-20! I used to look at that mic and never actually want to use it but I got to tell you — I used it on a demo session and was blown away! It already had a high-pass filter, it already had a sweet, smooth high-end and it didn’t need a pop filter because you could sing right up against it and it didn’t care. It was those kind of things that changed the way I think. Tom Dowd also taught me something important in the final mix stage. He didn’t just pan left and right, or 10 and two or nine and three o’clock. No, he ran 1kHz tone into the console on the channel that he wanted to pan and dialled the panner in. That was very laborious but, my god, the stereo imagery was perfect!”

English Lessons

Price spent seven years with Pablo Cruise and — after his brief stint as a roadie — began engineering both the group’s tours across the globe and their studio recordings. He quickly gained a reputation around the Bay Area of San Francisco, which led to further shows and tours with numerous local acts while he also retained his job at the world-famous Record Plant studio in Sausalito, California. In 1982, Greg was hired to live mix for country legend Glen Campbell, and it was during a subsequent trip to England with Glen that Price — who had always loved the sound of UK-produced records — got to witness some incredible engineering attention to detail.

Greg with one of his Pro Tools-based recording systems.“There was one recording session with Glen in England that really opened my eyes,” says Price. “It was a symphony thing with the London Philharmonic and it was amazing. I got a sense of how the English engineers seemed to be on a much higher level. They actually had the score in front of them so they had the roadmap of each song. Other engineers in the United States that I’d worked with never did that. There was this amazing attention to detail and this amazing absorption in doing the right thing. I just was flabbergasted; not only did they have the score in front of them, but the score related to how they were mixing the different sections of the orchestra. And that changed my view because that’s zone-mixing, if you will, where you have a zone perspective of what’s happening on the bandstand. That was huge! Even though this guy with the full chart in front of him had a 90-piece orchestra in the studio, you could just as easily dissect that approach for a three-piece band.

Greg with one of his Pro Tools-based recording systems.“There was one recording session with Glen in England that really opened my eyes,” says Price. “It was a symphony thing with the London Philharmonic and it was amazing. I got a sense of how the English engineers seemed to be on a much higher level. They actually had the score in front of them so they had the roadmap of each song. Other engineers in the United States that I’d worked with never did that. There was this amazing attention to detail and this amazing absorption in doing the right thing. I just was flabbergasted; not only did they have the score in front of them, but the score related to how they were mixing the different sections of the orchestra. And that changed my view because that’s zone-mixing, if you will, where you have a zone perspective of what’s happening on the bandstand. That was huge! Even though this guy with the full chart in front of him had a 90-piece orchestra in the studio, you could just as easily dissect that approach for a three-piece band.

“This was also the first time I saw a guy stop a session because he couldn’t get the sound he wanted, and he changed the microphone. And, as soon as he changed the microphone, the sound immediately came into fold. So often, people do a different thing and they start piling gear in and they do this, that and the other to get the sound. This guy simply changed the mic and, in three minutes, the sound happened. This was also where I learned about getting sound with a blank input strip — no EQ, no compression and no anything. You just need the right mics and the right mic placement. I remember going to a London studio where they weren’t even using the console. The engineer had his own specialised set of mic pres and he was going straight to the analogue tape machine. This really, really struck a chord with me because, back in the United States, everybody was going straight into the console, but these guys were doing it a whole different way. All this goes back to searching for the right sound, which is so important. Sometimes, there could be a bad channel on the console or there could be bad cabling going from the console to the tape machine. These guys eliminated all that copper, by running the cable in through the studio into the control room and straight into the tape machine. All this started to resonate with me — what happens to the signal flow from the diaphragm in the microphone to the tape head? I started thinking about all those things. Where does that signal travel? What is it going though? How do you manipulate the signal and the sound in the way you want to manipulate it? That’s what I learned from the English engineers and their amazing attention to detail.”

Another influential figure in Greg’s career is Tom Petty’s FOH engineer, Robert Scovill.

“The first tour I did with Robert was with Poison [in 1987],” explains Greg. “And, all of a sudden, I’m face to face with a guy who’s just dedicated to the science and the art of audio. Thirty years on, Robert and I are still friends and we still work shoulder to shoulder. If it wasn’t for Scovill and Avid [whom Robert introduced to Greg], Diablo Digital would not exist. These relationships with — in my view — some of the greatest engineers of our time have been so important.”

Blurred Roles

While Greg Price has spent the majority of his career on the road with bands and artists, he’s also notched up an inordinate amount of time recording in studios. Greg tends to see these two roles as essentially being the same thing.

Ozzy now uses a Shure Beta 58A capsule for his vocals, in part because of its water-resistant properties...Photo: Alberto Cabello“The line between being a live-sound engineer and a recording engineer is blurred,” says Price. “I treat the whole live-sound thing as if I am in one big recording studio. It’s no different to you and me sitting in a little workshop with a pair of nearfield monitors in front of a small console or being in Wembley Arena with a big PA system and my Avid console. It’s the same format. For example, I could be working with Tony Iommi [Black Sabbath guitarist]. Even though Black Sabbath are very established and have been recording and playing as a band for over 40 years, I still have that thirst to find a new unique sound and one of the things that’s so amazing about working with a guy like Tony is that he puts in the time. He’s willing to listen to me and he’s still searching too, which is just wonderful. Brad Madix, my partner and co-founder at Diablo Digital, share this same thirst for innovation. Brad and I actually met early on in my career and we now have a 30-year relationship. At Diablo Digital, we develop digital recording/playback machines that are very portable, very usable in the Pro Tools format and they can hook up to whatever console it is that somebody is working on. For instance, Tony and I could be in Birmingham, England, rehearsing. The band plays a couple of songs, then go off to have a cup of tea and Tony’s in my room and we’re listening to a playback of his guitar. The whole process is no different than if we were making a record. It’s like an album project but it’s a live show. We could be doing the same thing at a soundcheck and I could be recording what’s on stage; again, it’s like a studio. A Diablo Digital recorder enables the engineer to actually make a multitrack recording of eight different microphones on an amp so he can make an intelligent choice about what to use for a tour or for a show.”

Ozzy now uses a Shure Beta 58A capsule for his vocals, in part because of its water-resistant properties...Photo: Alberto Cabello“The line between being a live-sound engineer and a recording engineer is blurred,” says Price. “I treat the whole live-sound thing as if I am in one big recording studio. It’s no different to you and me sitting in a little workshop with a pair of nearfield monitors in front of a small console or being in Wembley Arena with a big PA system and my Avid console. It’s the same format. For example, I could be working with Tony Iommi [Black Sabbath guitarist]. Even though Black Sabbath are very established and have been recording and playing as a band for over 40 years, I still have that thirst to find a new unique sound and one of the things that’s so amazing about working with a guy like Tony is that he puts in the time. He’s willing to listen to me and he’s still searching too, which is just wonderful. Brad Madix, my partner and co-founder at Diablo Digital, share this same thirst for innovation. Brad and I actually met early on in my career and we now have a 30-year relationship. At Diablo Digital, we develop digital recording/playback machines that are very portable, very usable in the Pro Tools format and they can hook up to whatever console it is that somebody is working on. For instance, Tony and I could be in Birmingham, England, rehearsing. The band plays a couple of songs, then go off to have a cup of tea and Tony’s in my room and we’re listening to a playback of his guitar. The whole process is no different than if we were making a record. It’s like an album project but it’s a live show. We could be doing the same thing at a soundcheck and I could be recording what’s on stage; again, it’s like a studio. A Diablo Digital recorder enables the engineer to actually make a multitrack recording of eight different microphones on an amp so he can make an intelligent choice about what to use for a tour or for a show.”

One key word for Greg Price when he’s engineering a live performance or mixing a live recording is ‘sensitivity’. At a concert, he is looking to enhance an audience’s sensitivity to what is going on on stage to create that indescribable magnetism that characterises unforgettable gigs. And if Greg’s mixing a live show after the event, his aim is then to re-create the magic that was flowing from the stage during the original performance.

“I remember doing a show with Glen Campbell, and there were only three people on stage — Glen, Chet Atkins and Carl Jackson, who’s a famous banjo player,” Greg explains. “It was just the three of them on stage at the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville, Tennessee, and we’re talking goose bumps! The air was so thick with audio, it was just insane, and that is the sensitivity I talk about. No matter what the genre of music is, no matter where you are recording — whether it’s a studio or Wembley Arena — the aim is to excite the air with that audio sensitivity. It’s hard to explain, you can’t touch it and it evaporates after the event, but it’s just a thing that is there. That’s why Diablo Digital said, ‘OK, enough with this evaporation of the sensitivity after an amazing show!’ We will save the digital audio of it and, while we may not be able to capture the room and the air and the sensitivity at the time of the performance, we will still know what happened that day, so we can then try to recreate that. That’s what we’ve helped artists achieve. I’ve had different managers come up to me and say, ‘Greg, my band have recorded a live album and it does not sound the way it sounded when I experienced it in that room during the show! Can you help us out here? Can you go into the studio and recreate that experience for us?’ That’s what myself and Diablo Digital will do for them. I have heard from so many happy managers and happy artists after they’ve heard our mixes of live recordings. It’s always so important to work very closely with everyone involved.”

The Ozzman Cometh

Greg began working as FOH engineer for Ozzy Osbourne as a solo artist back in 1995. Two years later, it was announced that Black Sabbath would be reforming with their original line-up of Ozzy, guitarist Tony Iommi, bassist Geezer Butler and drummer Bill Ward. The job of live-sound engineer for their forthcoming reunion tour was up for grabs and Greg duly demonstrated his FOH skills at an early rehearsal.

“They called me and asked me to go to Rockfield Studios in the Monmouth Valley in the Wales countryside,” says Price. “So I ordered some microphones, got on a plane, flew to London and then took that long trip to the studio. When I walked in, they were ready to rehearse and they had all their instruments set up. So I met everybody and then they go ‘Right, can you record?’ and I’m like, ‘Oh shit, right...’ What could I do? So I said, ‘OK, could you play just maybe a verse of something to warm up a little bit?’ They did so and I stood in the room with them and I got one mic — an Audio-Technica [AT]4050 — and put it in omni. I put it about 10 feet in the air in the best single spot in the whole studio that I could find. I ran it into the wall, ran into the studio and they were already playing so I hit record. They played about three songs and then they stopped and they all start walking towards me, and I go, ‘Oh shit!’ Then they all sit behind me and they go, ‘OK, could you play that for us?’ This is a single channel, a single microphone, no compression and I didn’t even high-pass the thing but I hit play and the sound that came out of those speakers was mind-boggling! This was my test and they all go, ‘Fantastic, Greg, you’re hired!’ Geezer, who later on I found — along with Tony — was very articulate when it came to the music and the sound, stayed behind and he goes, ‘I’ve never heard my bass guitar sound that good!’ I just didn’t have it in my heart to tell them that there was only one mic in the room. I’d learned this approach from all of these mentors that we’ve talked about, particularly Bill Schnee, who was a genius as far as room-miking and mic sensitivity go — how you manipulate a mic, what pattern you use, and everything else. It was Bill that taught me to put a mic in omni in that situation. Most engineers would have left that thing in cardioid or super-cardioid and they would have been dead in their tracks. In omni, the thing is like a big balloon catching everything that’s in the room.”

Geezer Good

When it comes to miking Geezer Butler’s bass rig live, Greg Price has used a number of different microphones during the 18 years he’s been working for Black Sabbath. Here, he explains quite a bit more about his miking philosophy.

“When I first started working for them, I went back to the records and I researched how their producers at the time actually recorded Geezer’s bass,” explains Greg. “What was their process? A lot of this information is easily attainable and, once I’d got that, I just sort of applied that knowledge to his current bass system. I worked with him and his bass tech to develop something that was bigger and richer than what was on those records. I tried multiple different mics, everything from a valve mic to an [Electro-Voice] RE20. I settled on a very obscure mic. It’s called an Electro-Voice RE38N/D; it’s kind of a funny little thing but in addition I use an SE Voodoo ribbon. Here’s the thing about miking — you really need to go up on stage and listen at the speaker to the musician and what he or she is doing. Once you’ve listened to the speaker, then maybe you can make a decision as to what mic you might start on first. This is why I love rehearsals and using a full multitrack Pro Tools session, so I can put several different mics up and listen to all of them. That’s my process. Geezer plays through multiple 8x10 speaker cabinets with other cabinets thrown in, which means I can put a different mic on every single one of them during rehearsal. But then I also like the Pete Townshend theory: take a mic and put it 12 feet away from the amp. What does that do? Because arguably I can’t have a mic standing 12 feet in the middle of the stage while Geezer’s trying to perform, right? Well, doing that gives me another perspective and there are many places within a stage set where you could focus a mic 12 feet away.”

Greg is a big fan of Waves plug-ins.Phase is also always a key consideration for Greg. “Let’s talk about alignment,” says Price. “I learned this from Robert Scovill, and it’s the difference in time between, say, hearing a bass player through a DI and hearing it from a bass head with a mic in front of it. Those two inputs are offset by time, and it’s up to the engineer to root that latency out, especially when you have multiple inputs. I might be in rehearsal with the band with maybe seven or eight inputs and, not only do I have all those inputs to listen to, I also need to start focusing on the latency within the bass rig itself. The engineer needs to really find that latency — or delay offset, if you will — and make it all in line. Once it is in line, you can really start listening to things. I think if you don’t do that, you’re kidding yourself as to what you’re actually hearing, and when you put it through the big PA system at Wembley Arena... brother, you could have a problem! The PA system’s out in the audience so there could be a 10-metre differentiation between the front of my speaker system and the front of Geezer Butler’s bass rig, and those two entities need to come together at some point without disrupting the band and their performance. There’s a methodology to miking that is very, very scientific.”

Greg is a big fan of Waves plug-ins.Phase is also always a key consideration for Greg. “Let’s talk about alignment,” says Price. “I learned this from Robert Scovill, and it’s the difference in time between, say, hearing a bass player through a DI and hearing it from a bass head with a mic in front of it. Those two inputs are offset by time, and it’s up to the engineer to root that latency out, especially when you have multiple inputs. I might be in rehearsal with the band with maybe seven or eight inputs and, not only do I have all those inputs to listen to, I also need to start focusing on the latency within the bass rig itself. The engineer needs to really find that latency — or delay offset, if you will — and make it all in line. Once it is in line, you can really start listening to things. I think if you don’t do that, you’re kidding yourself as to what you’re actually hearing, and when you put it through the big PA system at Wembley Arena... brother, you could have a problem! The PA system’s out in the audience so there could be a 10-metre differentiation between the front of my speaker system and the front of Geezer Butler’s bass rig, and those two entities need to come together at some point without disrupting the band and their performance. There’s a methodology to miking that is very, very scientific.”

Guitar Tones

So what approach has Greg Price taken with miking Tony Iommi’s guitar amps over the years? “Again, with Tony, I started to listen to the original Sabbath recordings from the ‘70s,” he recalls. “I started to realise that most of these recordings were maybe done with a large diaphragm and probably a Neumann U87. Now, I did bring a U87 out early on, but it just didn’t sound right — but then vintage microphones are not all created equal and that’s another thing I learned from Bill Schnee. There are two mics I started with that I loved the sound of: an Audio-Technica AT4050 and its little brother the AT4060, which is a valve mic with its own PSU, and I used that mic on Tony’s guitar for years but I had a problem with it because I’d get my mic back but the guitar tech somehow would end up with my power supply and I’d never get it back! So I went to the 4050 and I didn’t think I was giving up too much ground. I could still get that sweet, sweet low end that is Tony Iommi’s signature sound, but without any piercing high end. I’ve got to say, Tony and I have an amazing relationship. I’ve never worked with a guitarist who’s so in tune with what I want to do. We’re always on the same page and it always works.”

Mastering Reality

Price also always ensures he has a great ‘static mix’. “I learned this from Tom Dowd, and Bill Schnee does it, Jack Joseph Puig does it, Tony Maserati does it... many great engineers do it!,” says Greg. “The static mix is when you get the mix up on your console and you do nothing but make sure the gain is right, bring the faders up and do nothing but high-pass filter and pan. It’s a pure mix of what you have in front of you and all you’ve done is trim the fat where it’s needed, trim the high end where it’s needed and then try to develop a spatial view of what it is you’re listening to in the stereo image. You can do this within segments of the band. I can have Tony Iommi’s guitar in a zone so I’ve got a static mix of all of his inputs in a stereo bus, and I’m mastering that bus. You can see the architecture here. The mic comes into the console, I’ve developed the stereo image of Tony’s guitar, at the end of the audio sub group I’ve mastered that sub group and — before the stereo bus even sees that input — it’s totally zoned, it’s totally mastered and it’s totally spatially viewed before the final stereo bus sees that sub mix.”

Kit Parade

With drums, Price is a big believer in using overhead mics on the stage to capture the ambience and magic of what’s happening on the drum riser. “Most engineers just want to close-mic everything,” he explains. “But about 10 years ago, I was listening to something and I think it was a Van Halen record. I just heard this fabulous room in the back of the recording and I thought, ‘I’m mixing in a room and I want to bring a little more of what’s happening on that 8x8 drum riser out into the room.’ I mix 120 feet away from the stage — that’s my sweet spot — because basically I want to be out where you are. I want to differentiate myself from the stage and be out with the people. I am also always on the floor with no riser because I want to experience what you experience in your seat. I want to bring that drum riser out to me and out to the audience. Anyway, I started experimenting with overheads. Now, Ozzy and Black Sabbath don’t use in-ear monitors and we measured 123dB SPL in certain spots on stage, which is approaching the threshold of pain, although in a lot of places it was a very mild and respectful 100dB! There are subwoofers on the drum riser and the drummer’s got fixed wedges behind him. Now, traditional engineers would go, ‘Why are you putting an ambient mic up over the drums? Are you out of your mind?’ That’s because they never learned the static mix. And I’d say, ‘Sure, I’m going to put that overhead up there but I’m going to high-pass filter it maybe to 200 cycles and not let the subs and all the low end of the drums get into that mic.’ Oddly enough, if you look at a snare drum at maybe 20 feet away using Smaart [see below], you’re not going to see 20 cycles, 40 cycles, 80 cycles or 100 cycles... No, you’re going to see that 400 cycles is the sweet spot of that snare drum, ambient in a room by itself.

“Smaart Pro is an analytical software tool that enables an engineer to not only analyse the inputs from his console, but also analyse the room itself at the same time. Smaart collects that data from your console and shows what you’re doing on your equaliser, as well as what the room itself and what the room mic is doing, so I use it a lot. I use my ears a lot too because I want to hear the resonant point of that snare drum in that given room and then I want to identify that frequency. So what do I do? I strip away all of its neighbours and let the resonant tone of the snare drum breathe. With overhead drum miking I’ve used everything from a Royer stereo mic to a single [Audio-Technica AT]4050.”

Water, Water, Everywhere...

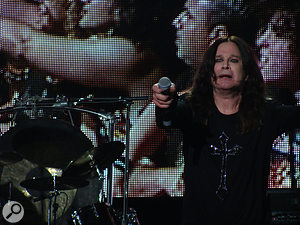

When Greg first started mixing for Ozzy Osbourne back in 1995, he very quickly came across a rather worrying issue on the stage — but the innovative FOH man soon found an effective mic solution.

“As I found out early on, there’s a lot of H2O on stage at an Ozzy show!” laughs Price. “If you’ve watched him before, you’ll know that he dunks his head in a bucket of water a lot. We used to have buckets of water flying everywhere and, as you know, water and electronics don’t mix! We were having problems with different mics and the water so I went to Shure and said, ‘Look I got a problem! We’d maybe like to use an SM58 but I’ve got a problem with water.’ First of all, Shure proceeded to completely disassemble the microphone to show me that there was a certain amount of moisture rejection in the building of the mic already, but then they said that the new product they were working on, the Beta 58A, was something they felt could take us to the next level. So I said, ‘Fine, let’s put a couple of extra precautions in and ship me a dozen of those capsules so that I can put them on Ozzy’s wireless stick, and let’s see how they go.’ Well, at the very first show, Ozzy’s got the mic and he actually drops the mic straight in the bucket of water! It was 100 percent submerged and he bent over, pulled the mic out of the bucket and went ‘Oh, that’s my mic!’ I could see the water just dripping straight off of it but he shakes it like a stick three times, starts singing and it was perfect! Since then, we’ve never used a different mic with him.”

Plug-in Baby

What plug-ins does Greg Price favour when he’s working on tour with Black Sabbath? “Plug-ins-wise, I’m a Waves nut” he exclaims. “I could close my eyes now and have a plug-in and an outboard insert and I couldn’t tell the difference, even between an [Universal Audio] LA-2A and a plug-in. And, even if there was a slight difference, the plug-in is going to win because I can’t keep shipping around a load of outboard. I used to but I can’t now. I mostly use Waves but there’s so many other good things out there. The Altiverb stuff is stunning, and so are the McDSP plug-ins, and then of course there’s Universal Audio’s amazing package... but remember, there’s a fine balance here. If we’re only in the studio and mixing in the box, everything’s on the table but it can be different when we go to a live show or broadcast because not everything works together and not everybody wants to do a handshake. For instance, Diablo Digital wanted to develop a way to put the Universal Audio package on a DiGiCo SD7, but you can’t do it — no handshake! And that’s where Waves have come along and really opened up Pandora’s box to give us every single Abbey Road plug-in for use on the SD7.

“I like to start with Waves because there is so much diversity, but then I think that the LA-2A plug-in that Universal Audio make sounds better than the Waves LA-2A... but at some point you have to kind of pick your fight, right? But I and Diablo Digital always have the full Waves Mercury bundle and the Studio Classics bundle. I usually stick with Waves and, if I can’t find what I want with Waves, then my next stop is McDSP. I really like the way their stuff works but then there’s these one-offs like [Cranesong’s] Phoenix, which is wonderful, and I also love the Sony Oxford reverbs.

As well as for recording gigs, Greg uses Diablo Digital recording systems to audition different microphones and mic positions captured during soundchecks.“Now, I’ve been an Eventide nut my whole life — and remember Ozzy triple-tracked all those vocals on the original records so it’s my duty to get that triple-track vocal sound out of him live. How the heck are you going to do that? In the old days, I had like six [Eventide] Harmonizers in my rack with an AMS reverb just to make it do what I wanted it to do but now you can stack a chain of plug-ins to make it do it. Waves have done a tremendous job in their Doubler program because it not only gives you the double but you can stereo image within the plug-in.”

As well as for recording gigs, Greg uses Diablo Digital recording systems to audition different microphones and mic positions captured during soundchecks.“Now, I’ve been an Eventide nut my whole life — and remember Ozzy triple-tracked all those vocals on the original records so it’s my duty to get that triple-track vocal sound out of him live. How the heck are you going to do that? In the old days, I had like six [Eventide] Harmonizers in my rack with an AMS reverb just to make it do what I wanted it to do but now you can stack a chain of plug-ins to make it do it. Waves have done a tremendous job in their Doubler program because it not only gives you the double but you can stereo image within the plug-in.”

On The Record

After Van Halen finish their North American Tour at the beginning of October, Greg Price will have two main priorities for the next 12 months. The first is preparing and then embarking on Black Sabbath’s 2016 World Tour, which he declares will be “very long” but which he understandably couldn’t be more excited about, while the second is continuing to expand the horizons of Diablo Digital with his business partner Brad Madix. Their live-sound recording company has enjoyed significant success since it was first formed in 2013. And while Price is over the moon that their recording systems have thus far been used by big bands like the Rolling Stones, Fleetwood Mac and U2, 2016 will see he and Brad pushing deeper into the opportunities provided by ever-evolving social media.

“The next step we see for Diablo Digital is developing a YouTube pre-emptive-type solution for bands and artists,” enthuses Greg. “At the moment, you’ll get that idiot standing in front of the sub-bass taking a live video of the songs and then putting it on YouTube. Everyone’s watching it and it sounds horrible and it looks horrible. What we are going to do is record it on show day, fix it on show day, embed it with the director’s cut on show day and so, next morning, their live video is up on YouTube in high quality! So the biggest focus for Diablo Digital is to really help bands with their social media, audio and video. It’s important for established artists and artists who are just beginning, and we’ve really focussed this thing to make it as inexpensive as possible.”

Black To The Future

Greg Price tells us about the PA system and console that he is aiming to take out on tour with Black Sabbath in 2016: “I want to use the brand-new Cohesion 12 PA system that Clair Global have designed, and which U2 have on tour right now. It’s a brand-new system that has spent many, many years in development. Clair Global have some of the brightest, most energetic, most dedicated people I’ve ever met and I’m just proud and honoured to be working with them.

“As far as the console goes, Brad and I have been working as much as we can with Avid and advising them. I plan on taking the brand-new and ‘in development’ S6L console. The S6L completely resonates with Diablo Digital as it enables Brad [Madix] and I to have these consoles either on tour or at our studio, doing mixes and having the ability to develop content for clients around the world. Diablo Digital are already working on a beta version of the new S6L console, and we have it in our studio. It’s exciting!”