K‑pop is a truly global music style, and BTS’s successful assault on the US charts was led by a British mix engineer.

K‑pop band BTS, aka Bangtan Boys, made history in May when their third Korean‑language album, Love Yourself: Tear, became the first K‑pop album to reach number one in the US. The album was also a big hit in many other Western nations, including the UK, where it reached number eight. Following K‑pop’s first worldwide megahit, Psy’s ‘Gangnam Style’ in 2012, this was another landmark moment for Korean music.

Bangtan Boys, also known as BTS, have become the most successful K‑pop band so far.Modern K‑pop has been around since the early 1990s, and draws heavily on Western popular music styles. K‑pop acts tend to be the South Korean equivalent of Western boy and girl bands, with attractive young singers performing music made for them by others, and BTS’s Wikipedia page states that the band were “formed by Big Hit Entertainment”, one of South Korea’s largest music companies. The seven‑piece have since become K‑pop’s biggest act, the most retweeted artist on Twitter, and this year topped the Forbes Power Celebrity list, which ranks the country’s most influential celebrities.

Bangtan Boys, also known as BTS, have become the most successful K‑pop band so far.Modern K‑pop has been around since the early 1990s, and draws heavily on Western popular music styles. K‑pop acts tend to be the South Korean equivalent of Western boy and girl bands, with attractive young singers performing music made for them by others, and BTS’s Wikipedia page states that the band were “formed by Big Hit Entertainment”, one of South Korea’s largest music companies. The seven‑piece have since become K‑pop’s biggest act, the most retweeted artist on Twitter, and this year topped the Forbes Power Celebrity list, which ranks the country’s most influential celebrities.

BTS consists of three vocalists and four rappers, and unlike many K‑pop acts, band members often co‑write their songs. The band’s most prominent behind‑the‑scenes songwriters are Bang Si‑hyuk, aka ‘Hitman Bang’, the founder and CEO of Big Hit Entertainment, and Pdogg, winner of the Best Producer Award at the 2017 Mnet Asian Music Awards. Unsurprisingly, given that Western influences are dominant in K‑pop, Western songwriters, mixers and producers are regularly involved. In the case of BTS, the list included Chris ‘Tricky’ Stewart (Katy Perry, Beyoncé), top EDM artist Steve Aoki, and DJ Swivel (Beyoncé, the Chainsmokers).

The Rise Of Sir James

One unsung Western hero behind BTS’s astronomical success is British mixer and producer James F Reynolds. From his Beach Studios in West London, Reynolds recalls: “I have worked with BTS pretty much since they started. They did some research stylistically when they were looking for the right mixer for their sound, and then got in touch with my manager. I ended up talking with Mr Bang, and I have since mixed all their singles, including ‘Fake Love’ [the lead single from Love Yourself: Tear]. I tend to do the Korean‑language versions first, and then later mix the Japanese‑language versions. You’d think I’d just push the latter through the same chains, but with seven singers, there are tons of backing vocals, and you’re talking 50‑60 vocal tracks that need replacing, so it’s not quite as simple as that! I also co‑wrote and co‑produced a track on their previous album, ‘Am I Wrong.’”

One unsung Western hero behind BTS’s astronomical success is British mixer and producer James F Reynolds. From his Beach Studios in West London, Reynolds recalls: “I have worked with BTS pretty much since they started. They did some research stylistically when they were looking for the right mixer for their sound, and then got in touch with my manager. I ended up talking with Mr Bang, and I have since mixed all their singles, including ‘Fake Love’ [the lead single from Love Yourself: Tear]. I tend to do the Korean‑language versions first, and then later mix the Japanese‑language versions. You’d think I’d just push the latter through the same chains, but with seven singers, there are tons of backing vocals, and you’re talking 50‑60 vocal tracks that need replacing, so it’s not quite as simple as that! I also co‑wrote and co‑produced a track on their previous album, ‘Am I Wrong.’”

What Mr Bang found when he did his research was that Reynolds has an impressive list of credits, including Paloma Faith, Ellie Goulding, Emeli Sandé, Calvin Harris and Tinie Tempah. Presumably Mr Bang also noticed that Reynolds was an artist and beatmaker for many years, while the fact that he also is a baronet is obviously not relevant in this particular context. Reynolds, while proud of his family history, is discreet about it within the music industry.

School Of Pop

“I’m originally from Jersey and went to school in Sussex. I learned to play piano as a teenager, but wasn’t really planning on having a music career, until I hurt my leg badly in an elevator in Paris, and then spent a year recovering at home. This was in the early ’90s. During this time I started writing songs, and I bought a four‑track and some mics to record them, and that got my inquisitive brain interested in engineering. So I went on to study engineering at the Gateway School of Music at Kingston University. When I graduated in 1995 I hooked up with a wealthy gym owner who wanted a kind of Stock, Aitken and Waterman‑style production team. He had a studio called Hit House, and I brought in Matt Schwartz, who has since become a quite well‑known writer and producer, who has worked with Massive Attack and Trevor Horn. Together we made tons of records.

“From there I went more and more into house music and made records with Soul Avengers, Hoxton Whores and Mark Knight, amongst others. Later I also was into garage. From my studio in Brick Lane [East London] I made tons of records for DJs, and also many records as an artist, under various names, like SuperMal, London Connection and Felix Baumgartner — the latter is my mother’s maiden name — and with Ben Braund in Braund Reynolds, and so on. I signed with Defected Records, a well‑respected house music label, and hooked up with singer Miriam Grey, and then with my manager, Dobs Vye, who turned out to be a great singer, and we spent five years making a record under the name Public Symphony [released in 2006], which smacks of Pink Floyd here and there, and got quite a lot of good press and is still out there. That all added to my skill set as a mixer, as we had incorporated many live instruments, including guitars, and I had to learn how to record and mix them properly.

“Fifteen years ago, I moved to Parsons Green and set up the studio where I am now. Over time, I came to the conclusion that the thing I enjoy the most is production and mixing, so I focussed more and more on that. My lucky break in the mixing world came with Tinie Tempah’s first album, Disc‑Overy [2010]. I had to beat off competition from some well‑known mixers, but I think coming from a dance background really translated well into hip‑hop and urban music, as I was used to dealing with lots of bass and bottom end and making everything sound punchy. My background as an artist and producer still is important, as it is necessary for a mixer today to have some production skills as well, so you can tell whether sounds used in a track need replacing.”

James Reynolds’ own facility in West London is called Beach Studios.

James Reynolds’ own facility in West London is called Beach Studios.

Out On A Limb

When Mr Bang contacted Reynolds in 2013, the mixer had gone on to work with quite a few more big‑name artists. He has typically used a fair amount of outboard, though recent years have seen Reynolds working increasingly in the box. Reynolds used to mix in Logic, but three years ago the mixer went further out on a limb, becoming probably the first, and perhaps the only, top‑level mix engineer who works in PreSonus’ Studio One DAW.

“It’s almost too painful to talk about, but I started on Notator in an Atari 1040,” explains Reynolds. “I then was on Cubase for a while, and then I switched to Logic. I stayed in Logic for a long time, rather than moving to Pro Tools, because I found Logic more creative. But when I discovered Studio One I really liked it, and today it is absolutely perfect. Many Logic and many Pro Tools users have moved over, because Studio One does what both of them do. Studio One’s mixing capability is much better, and the automation is much tighter in large sections with lots of plug‑ins. There have for a long time now been problems with the engine in Logic where the automation slips and goes out of time if your session is very big, and that was always very frustrating as it did not feel accurate.

“Pro Tools and Studio One are very similar, because Studio One is designed to make it very easy to convert to for Pro Tools users, who would find it a piece of cake. Where it differs is in the drag‑and‑drop workflow, which is super‑fast. You have a sidebar with all your plug‑ins listed in your folders, and you just pull a plug‑in on the channel or the bus, and it will set up the routing for you. It is designed to be super‑quick. It has also taken a leaf out of Ableton’s book, so all your samples can be previewed real‑time and will automatically loop in time. Plus it has gone next level, for example in that you can create splits of your plug‑in signals within your channels. So let’s say you have a lead vocal, and you want to do a parallel bus for it within that channel, you do the split inside the plug‑in, and this gives you a lot of control very easily. It is all very well thought‑out and the automation is fantastic, and so is the MIDI.”

As an ambassador for the product, Reynolds has collaborated with PreSonus on the development of the new Studio One 4 [reviewed SOS August 2018], and in using it for his work he’s putting his mix activities where his mouth is. With regards to the rest of his work environment, he adds, “My hub is my Yamaha DM2000 console, which I can use as a controller or sometimes spread my mixes out on. Though, generally speaking, I am fully in the box. The tape emulation and compression plug‑ins are so good now, and also, the norm is for endless recalls from the labels, so when you have a few mixes going on at the same time you need to be able to pull up your mixes instantly. The DM2000 mostly functions as a conduit to route a signal to my Bricasti M7 [reverb], and to spread all my reference mixes across on, including tracks that are influences, so I can easily flick between what I am working on and my reference tracks.

”I have a Thermionic Culture Mastering Plus compressor on my mastering bus, and sometimes an Avalon VT‑747sp compressor. I use these if I’m doing a more band‑based project and want more of an analogue vibe. I also have a Manley Gold microphone, as well as a John Hardy mic pre, and Apogee Symphony I/O. My monitors are going through a bit of a transition at the moment, as I’ve been mixing for several years on PSI A25 monitors as my main speakers and OS Acoustics DB7s as my mids, and my trusty Avantones. I have my PSI A25’s rigged up to a Trinnov SP2‑Pro room correction box, which does very hi‑tech acoustic analysis, and measures phase relationships between your speakers and makes things very accurate for your listening position. That said, I just had the Kii Three monitors in for the last few weeks, and they are just incredible. They really herald a new era of speaker, with a lot of hi‑tech to stop phase [issues] and standing waves. I haven’t had anyone come in my studio who hasn’t been blown away. You know you’re listening to good speakers if you’re playing with nuances on reverbs and things like that, and you can really hear them!”

Preparation Is Key

All the above was put to good use in Reynolds’ mix of ‘Fake Love’, the lead single from Love Yourself: Tear. Containing 150‑odd tracks, the session gives a good insight into the ins and outs of a K‑pop production, as well as Reynolds’ Studio One mixing methods. “Because I’m not mixing in Pro Tools, when people send me a mix, I ask for processed stems, without their master bus processing on. However, I like to receive the vocals as dry stems. If they want me to use their vocal effects, I ask that they send them as separate stems. I also ask for the Pro Tools session, so if there is something that I want to undo, I can open it up and get the raw file without the plug‑ins on.

“The BTS productions that I am sent are always very well considered and thought out, which makes them a pleasure to mix. In the case of ‘Fake Love’, I think they sent me 146 stems. There are a few tracks that are hidden in my mix session, because they were bounced. When my assistant preps the session he will bounce some things, like backing vocals, down to single stems. The BTS producers are very good with naming the tracks. If that isn’t the case, I’ll do the naming myself, because you have to be organised for a big mix session, or you’ll go bonkers. But with BTS I also like to keep the original naming, because when they ask me for revisions and tweaks they refer to the track names to the letter, so keeping these names also helps to prevent confusion.”

Take Your Time

Once his assistant has prepared the mix session, Reynolds is ready to get to work. “The first thing I do is I spend some time listening to it, and I read through all the information from the producer and the label owner as to what they are hoping to get out of the mix. I listen to the rough and think about it and gather my thoughts as to what needs to happen, and I make notes. If you jump in too quickly, you might end up going around in circles, not quite knowing what you are trying to achieve. So I try to establish areas that I think can be improved upon, and stuff that I think is great and does not need touching, and then I get on with it. The most important thing when mixing is to understand what is needed. It is a skill in itself knowing when not to do too much!

“Especially when you have a track of the size of ‘Fake Love’, with so many parts, there is some very basic stuff that needs to happen to make enough room for everything to work in a mix. Mostly this is just EQ management of high end and low end. I go through all tracks and just cut away any unnecessary low end, literally topping and tailing where necessary. If you do this on every channel it makes an enormous difference. I have a few EQs that I use for that, like the DMG Audio EQuilibrium, which I think is an amazing EQ with a huge amount of flexibility. The other EQ that I am a big fan of is the FabFilter Pro‑Q 2, which is a good surgical EQ. The feature where you hover your mouse over it and it takes a snapshot of the curve of whatever you are listening to over that period makes it easy to find any nasty resonant frequencies and pull them down. For more vibe, I love the UAD Harrison EQ and the Eiosis AirEQ Premium.”

Well Presented

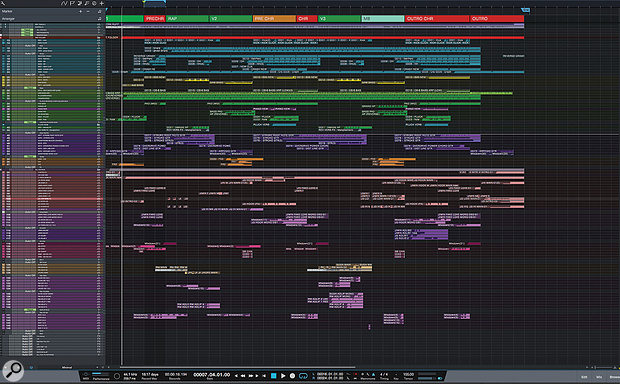

James Reynold’s Studio One session for ‘Fake Love’ is meticulously organised. The structure is clearly delineated at the top, and in addition to the 146 clearly coloured audio tracks, there are two main busses (‘Instrumental’ and ‘All Vocals’), plus 24 busses for individual instrument or vocal types. The former include Kick, Snare, Drums, Bass, Pluck Reverse Crystallizer, Chorus Plucks Bus, Keys Synths, Guitar and FX, while the vocal busses are Vocal Main, Doubles, Ad Libs, SB Vocal, Rap Main, Rap Doubles, Rap Ad Libs, Why and BGV. Below that are seven effects tracks containing a chorus, half‑note delay, FabFilter Pro‑R reverb, quarter‑note delay, UAD EMT 140 reverb, 16th‑note slapback delay, and ‘reverb slap’.

This zoomed‑out view shows the entire PreSonus Studio One arrange page for the ‘Fake Love’ mixing session.

This zoomed‑out view shows the entire PreSonus Studio One arrange page for the ‘Fake Love’ mixing session.

Talking the reader through the entire session would take up the rest of the magazine, so Reynolds opts to highlight some, er, highlights. His signal chains feature numerous plug‑ins that do not normally make an appearance in the Inside Track series. “My interest is in plug‑ins that are really innovative and different and that make you think a little laterally,” explains Reynolds. “I don’t use Studio One plug‑ins, although they have loads of really good stock plug‑ins that I know some people swear by, because I spent so many years mixing with plug‑ins that I got used to, that I just stick with them.”

This diverse selection of plug‑ins is used on the kick drum bus.

This diverse selection of plug‑ins is used on the kick drum bus.

- Kick: DMG Audio EQuilibrium, Empirical Labs Arousor, Wavesfactory Spectre, Kazrog KClip Pro, Vengeance Transmitter V3 & DMG Audio TrackControl.

“My process with the kick is using EQuilibrium to tidy up a little bit of bottom end, then I have the Arousor, of which I am a big fan, and which has a similar character to the Distressor. It adds a nice bit of punch to the kick. Next is a fairly new plug‑in called Spectre, which is brilliant, and which adds harmonic content, rather than just being an EQ. You choose what kind of enhancement you want from your EQ, whether it is tape or any other option. I added that right at the end of the mix just to give a bit more weight around 84.86Hz. Then I have KClip, for 2‑3 dB of clipping and a bit of saturation. That plug‑in sounds brilliant on drums. From there the signal goes to the Vengeance Transmitter, which is sending the signal into the Vengeance multiband side‑chain on the Bass bus. Every time the kick hits the Vengeance is ducking by the amount I have set on the multiband side‑chain. At the end of the channel I have the Track Control for trims and levels.”

- Snare: FabFilter Pro‑Q 2, iZotope Neutron Transient Shaper, UAD Ocean Way & Goodhertz Vulf.

“The snare is quite simple: there’s a bit of maintenance cutting top and bottom with the Q2, with a little hump just below 500Hz to bring out the weight of the snare. Then I have a Neutron Transient Shaper, and I am using it to push up the high mids to get a real crack out of the snare. There’s also another ghost snare, the ‘vibe perc snare’, on which I have the Vulf, which is a very vibey, slightly vintage‑sounding compressor, which can sound brutal. Sometimes brutal is good! It has a great sound to it, and it is compressing the room, which came from the Ocean Way plug‑in, which is great for realistic‑sounding space.”

- Drum bus: Soundtoys Decapitator & DMG Audio EQuilibrium.

“My kick goes directly to the master bus, but all the other drums go to this bus, on which I have the Decapitator to add some saturation, and a tiny bit of EQ to tidy up some bottom and top end. I already had EQ on the individual channels, so I’m just making doubly sure of these things here. I have a fairly basic drum bus going on here.”

The bass part in the chorus was initially too lacking in overtones to be audible on small speakers, so Reynolds used several plug‑ins to generate additional harmonic content.

The bass part in the chorus was initially too lacking in overtones to be audible on small speakers, so Reynolds used several plug‑ins to generate additional harmonic content.

- Chorus bass: UAD Little Labs VOG, UAD Vertigo VSM‑3 & iZotope Trash 2.

“The original chorus bass was just a very low sine wave, really, that would not have come across on smaller speakers. I have a set of Avantones in here, and I wanted to make sure that you could feel and hear the bass on them. So it went through several saturation and harmonic booster plug‑ins. It started with the Voice Of God to fatten the bottom end, and then I added the VSM‑3, set to saturate mids and lows. These two are relatively subtle, and the last plug‑in is the iZotope Trash 2, which is putting some serious overdrive on the signal, which is why you can really hear it as well as you can.”

- Lead arpeggiated guitar in verse: Slate Digital Virtual Mix Rack, Oeksound Soothe, FabFilter Pro‑Q 2 & DDMF Directional EQ.

The arpeggiated guitar in the verse also received heavy plug‑in treatment.“The Mix Rack adds EQ, saturation and compression, and is followed by the Soothe, which does some real magic. It saves you messing around for ages, trying to find all the different nasty frequencies you don’t want! Here it pulls out a couple of frequencies that were getting in the way of the mix. Next is the Pro‑Q 2, which is cutting below 35‑40 Hz, and then the Directional EQ, which is really handy for placing a signal in the stereo field so it becomes a bit more apparent on the left or the right. You might want certain high frequencies on the right so they don’t clash with other high frequencies from a different instrument on the left, for example. It is a really handy stereo‑manipulation tool that allows you to get a really wide mix where you can hear everything that is going on.

The arpeggiated guitar in the verse also received heavy plug‑in treatment.“The Mix Rack adds EQ, saturation and compression, and is followed by the Soothe, which does some real magic. It saves you messing around for ages, trying to find all the different nasty frequencies you don’t want! Here it pulls out a couple of frequencies that were getting in the way of the mix. Next is the Pro‑Q 2, which is cutting below 35‑40 Hz, and then the Directional EQ, which is really handy for placing a signal in the stereo field so it becomes a bit more apparent on the left or the right. You might want certain high frequencies on the right so they don’t clash with other high frequencies from a different instrument on the left, for example. It is a really handy stereo‑manipulation tool that allows you to get a really wide mix where you can hear everything that is going on.

"As I mentioned, I like plug‑ins that are a bit different. Another example is the Sound Radix Surfer EQ, which I use a lot, though not in this mix. Sound Radix are a next‑level company, and their Surfer EQ allows you to EQ specific harmonics, and then set it to move with the harmonics that you have chosen, which is very clever.”

- Lead distorted guitar in chorus: iZotope Trash 2, Soundtoys Effect Rack, FabFilter Pro‑Q 2 & Noveltech Character.

“I also have the Trash 2 here, set on a multiband, so I could have a bit more control over the type of overdrive on different bandwidths. The Soundtoys Effect Rack was used to create a space around the guitar, a real stadium type of vibe, using EchoBoy and Crystallizer and Sie‑EQ — I’m a big fan of the latter. Then I have the Q 2 again tidying up the low end at the end of the chain. The Character is just enhancing the guitar and gives it a bit more presence in the mix.”

- Rhythm guitar: DMG EQuilibrium, FabFilter Pro‑Q 2, Vengeance VMS Stereo Bundle, Blue Cat Destructor, FabFilter Pro‑Q 2 & FabFilter Pro‑R.

“This rhythm guitar also has a real vibe to it, but it did not need to stand out too much. In terms of the channel strip, EQuilibrium was doing a tidying‑up job, the Q 2 was notching out a couple of slightly annoying resonant, twangy strings, the VMS was widening, the Blue Cat was adding a bit of saturation and distortion, the Q 2 was tidying up any mess that might have been created by the distortion, and I added reverb with the Pro‑R.

"In addition, there’s a plug‑in made by Zynaptiq Audio that I am a massive fan of called Adaptiverb. It is quite an unusual reverb because it adds in harmonics, like fifth and seventh harmonics, into the sound in the reverb. This creates really wonderful musical pads and textures. I put the rhythm guitar through this, on full mix, and then bounced it out to the channel below it. The Adaptiverb reverb channel creates an amazing space around the guitar.”

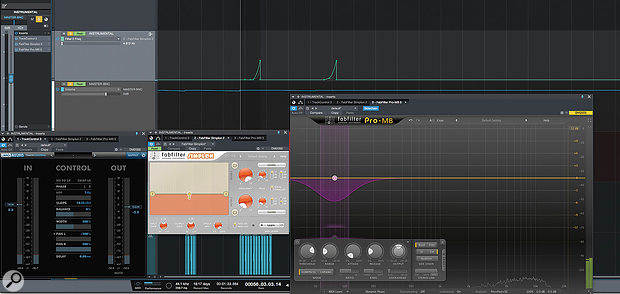

Everything apart from the vocals and kick drum was routed to the ‘All Instruments’ bus and its plug‑in chain.

Everything apart from the vocals and kick drum was routed to the ‘All Instruments’ bus and its plug‑in chain.

- ‘All Instruments’ bus: DMG Audio Track Control, FabFilter Simplon & Pro‑MB.

“Apart from the kick, all instruments are routed to this bus. I sometimes have two instrumental busses if I am doing certain side‑chains. In that case I’ll have one instrumental bus with a side‑chain set up, and one with none at all. In this track I have just the one instrumental bus, and it has the DMG Track Control for volume and high‑pass filters and things like that, followed by the FabFilter Simplon. The green automation line is for the Simplon, and just before the choruses I take a little bit of weight out, so when the chorus drops all the weight comes back in and it gives that sense of the chorus growing massive. It adds movement. After that there’s the Pro‑MB, and this is the reason why my kick always routes straight to the master bus. The Pro‑MB is set up to receive an external signal, and every time the kick hits, it pulls some 50‑100 Hz out of the instrumental bus in the Mid but not the Sides, so the kick remains really present in the mix.”

- Jimin chorus lead vocal: iZotope Neutron, FabFilter Pro‑MB, Empirical Labs Arousor, iZotope Trash 2 & FabFilter Pro‑DS, plus sends to Slate VerbSuite Classics, FabFilter Pro‑R, Soundtoys EchoBoy, Waves Factory Trackspacer & FabFilter Pro‑DS.

“Welcome to my vocal world! BTS like bright, punchy vocals. There is not a lot of room in the mix because there is a lot of stuff going on, so I am not boosting low end on the vocals, because you are not going to hear that. Instead I’m trying to give the vocals more presence. The first thing I have in the chain is Neutron, which is a great EQ, and I love its dynamic mode. I boost high end with the Neutron, and band three is set to 4‑6000 Hz, with the dynamic mode pulling down any loud ‘ess’ sounds or anything else too sharp. The Neutron is also tidying up the bottom end. After that is the Pro‑MB multiband compressor just reining in a couple of frequencies to control the vocal.

“Next is the Arousor, adding some distortion so the vocal is very spitty and present, with lots of attack. After that there’s another instance of Trash 2 set to multiband, which I am using to give the vocal drive and really making it sit solidly in the mix. You have to know how to use Trash 2, otherwise vocals can get too harsh, but in general it is a very good way of saturating and really thickening a vocal and giving it presence. It does depend on the song, I am not always so full on with a vocal! At the end I have the Pro‑DS de‑esser just controlling the sibilance. Sometimes I used two instances of it, one at the beginning and one at the end, but the Neutron is already kind of doing a de‑essing job.

“There also are many sends on that lead vocal. The first send is going to one of my favourites, the Slate VerbSuite Classics. It’s set to a hall‑type reverb with 1.75s decay, and because I set quite high pre‑delays it is almost like a slap on the vocal, which puts the vocal in a nice space. The next send is to the Pro‑R for a longer, bigger reverb, which works for a chorus. I have cut low end and high end as you don’t want that floating around. The Pro‑R is really good for controlling those things. Next is an EchoBoy quarter‑note delay, saturated by setting it to ‘Splattered’ under ‘Style’ and that send then goes into the Trackspacer. I have a send from the lead vocal going to Trackspacer, so that whenever the lead vocal is singing the Trackspacer ducks the quarter‑note delay out of the way. The Trackspacer is frequency‑dependent, so it will duck whatever frequencies are dominant in the vocal, which makes it great for moving stuff out of the way. Then there’s another half‑time EchoBoy delay setting, which is being automated for delay shots, and finally another Pro‑DS.”

Achieving a lead vocal sound that cuts through the mix without coming across as harsh required something of a balancing act from James Reynolds, not to mention the use of numerous plug‑ins!

Achieving a lead vocal sound that cuts through the mix without coming across as harsh required something of a balancing act from James Reynolds, not to mention the use of numerous plug‑ins!

- ‘All Vocals’ bus: Overloud Tapedesk, DMG Audio EQuilibrium & Kazrog KClip.

“This is pretty much my standard chain. I have the Tapedesk as my first plug‑in. I love mixing into this, because I love the saturation that it gives to vocals. This is followed by the EQuilibrium, which notches out some high end. The Eiosis Air EQ Premium is next and does something slightly more interesting, because I am automating it with the green automation line. I use the automation to turn the Strength slider fully up for the pre‑choruses and the choruses, which adds real excitement to all the vocals in these areas. Then there’s the Pro‑DS de‑esser set to a pretty high threshold, because I have already de‑essed on the individual tracks. It’s just to catch anything else that I may have missed. Finally the KClip is just catching any remaining peaks.”

- Master bus: Sonalksis FreeG Stereo, DMG Audio EQuilibrium, SoundSpot Overtone, UAD Massenburg DesignWorks, Pro Audio DSP Dynamic Spectrum Mapper, Mastering The Mix Levels & Klanghelm VUMT.

“First off I have the FreeG gain plug‑in, because once the mix is approved, I do some gain‑staging so I am not slamming everything as hard before sending it to the mastering engineer. Next is the EQuilibrium, which does a high pass below 20Hz, a side cut sloping gently down 40Hz, a boost at about 117Hz, increases the width of it slightly around 500Hz, and finally there’s a high boost. So it is kind of a mastering EQ. The Overtone also is an EQ but it feels and sounds like saturation, so I am using a bit of that. This particular chain then had the Massenburg EQ, just because I love the sound of it. Here it’s doing a cut at the bottom end, and adding a tiny bit of presence. It just worked for the sound that I wanted.

“Next up is the Dynamic Spectrum Mapper, which is a fantastic multiband compressor. The orange line at the top represents the loudest part of the song, and then you bring the threshold down and push the gain into it, so it is compressing, but sensitive to the frequencies of the song. It has always been a big favourite on my master bus. Next up is the Levels plug‑in from Mastering The Mix, which I set to LUFS. It measures an average of 3 seconds, so you get a general feel for the volume over 3 seconds. I put all my reference tracks into the same meter, so I can make sure that everything I am working with is always at the same level, and my ears are not being fooled into thinking that because my mix has become slightly louder, it is better. The end of the chain is the Klanghelm VUMT meter, set to K‑14.”

Getting The Basics Right

James F Reynolds says that there are a number of common faults that he encounters when he starts mixing a session. “One of them is having the wrong sound for a song. Take, for example, kick drums. With less experienced producers, you sometimes get sessions where there are three or four kick drums layered on top of each other and they are fighting each other and sort of cancelling each other out on the bottom end. It often is a case of finding the predominant one or two and making them work together, or just replacing them. I also quite often add a small kick sound that I put on top just to make it come out a little bit. It is amazing what a tiny click sound can do psychoacoustically for your kick drum. From my own experience of building tracks, if I am spending hours layering sounds, it is just not right. You just have to find the right one. More experienced producers often have lower track counts, because they use better sounds and understand the space used by each part in the track.

“Another common mistake is for vocals to be over‑squashed, and sounding too harsh. The vocals are pushed pretty hard on ‘Fake Love’, but that is how they like their sound with BTS, because they like things to be quite hard‑hitting and cutting, which fits their style of music. But I often find that people load tons of plug‑ins on a channel or a bus, and this takes the character out of the original sound. So I often need to undo that. These are the situations in which I dig back into the original session to get the raw files.

“It is actually something I often notice when I work with a new assistant: the sheer quantity of plug‑ins that they tend to put on every channel, trying to make things sound loud! They may put on 15 plug‑ins, whereas you can probably do it with four or five. It is very easy for your ears to be fooled into thinking that something is better when it’s slightly louder, but if you volume‑match things, and put a simple EQ and compressor on, you will tend to find that it sounds better. The other thing is knowing how to use reverbs, particularly when to use pre‑delay to get the reverb out of the way of the vocal so that it still comes through. And understanding how to use reverbs and delays to sit everything in the right place in the mix. Not everything can or needs to be up front.”

Reynolds adds that he doesn’t encounter issues like these with BTS, because “Mr Bang and Pdogg are great producers.” There are nonetheless, he says, some unique challenges to mixing K‑pop: “The producers like quite a hip‑hoppy feel on their records, with big bottom end, and the songs tend to float between trap and hip‑hop and dance. The challenge with a lot of K‑pop stuff, especially BTS, is that it’s not like a traditional record where the entire song is more or less in one style. With K‑pop they switch from style to style within a song, and so one minute you’re mixing a hip‑hop vibe, and the next it’s going trap, then it’s four‑to‑the‑floor dance. That has been a trademark of K‑pop for years. It takes longer than normal to mix, as you need to focus on each section and make sure it works stylistically, and then you need to make it all gel together. That can be tricky as they may even have different drum sounds for each section! But on this particular song it was a bit more constant, with the drums remaining the same throughout, which made it easier to mix.”

Close Analysis

Reynolds’ second monitor, set permanently to display various metering plug‑ins, is visible in this shot of the mixer at work.

Reynolds’ second monitor, set permanently to display various metering plug‑ins, is visible in this shot of the mixer at work.

“I have two screens when I am mixing,” says James F Reynolds. “The left one shows the Studio One arrange window, and the right one has a number of plug‑ins that show me what is going on in my mix. The window on the left looks like a Christmas tree! That is part of the Flux Pure Analyzer System, which takes its feed from my master bus. The ‘Christmas tree’ window shows me the frequencies that are there and their width. I always make sure that I don’t have too much wafty stuff going on below 100Hz, and instead keep those low frequencies quite narrow.

"Another window is showing me the phase of the track, and another one is a spectrum analyser. The Mastering The Mix Levels and Klanghelm VUMT meters on the master bus are also showing here.”