Ian Fitchuk at Blackbird Studios in Nashville.

Ian Fitchuk at Blackbird Studios in Nashville.

Working with Kacey Musgraves catapulted Ian Fitchuk from respected producer to one of Nashville’s busiest songwriters.

“For about 10 years I was very much outside the mainstream,” recalls Ian Fitchuk. “It allowed me to work as a producer and session musician with very different types of bands and artists. I had a respectable arc of work and a lot to be grateful for. At one point I was like, ‘Wow, I can support my family and don’t need to get another job, and while I don’t live in a mansion and have a car that needs work done all the time, life is pretty good.’

“Then, in 2016, everything changed. I signed my first publishing deal, with Razor & Tie, which turned into Concord. I had played on Kacey Musgraves’ second album, Pageant Material [2015], and one day Kacey’s publisher reached out about co‑writing. I invited my friend Daniel Tashian, a songwriter and multi‑instrumentalist I admire, because I thought that things would click between the three of us. My guess was accurate.

“The three of us co‑wrote and co‑produced Kacey’s fourth album, Golden Hour [2018], which became a big success. It changed my life. Golden Hour was not defined as only part of the country genre. I remember chatter about the record changing country music, and I’ve since had a lot more interest from artists outside the country world. This works for me, because I love working on all kinds of music.

“I’m interested in being challenged, and I’m grateful that the first thing I became known for on a big level was something that I had been able to put a lot of myself in, musically and aesthetically. Some people call it organic, timeless music. Music with heart became my calling card. When people reach out to me now as a co‑writer and producer, they’re not necessarily looking to make a country record. They’re looking for my ability to tap into whatever their essence is. It means that I am learning new things, and starting from square one, every day.

“I’m working with artists who are not only interested in creating songs, but also in the concept of an album, the presentation, the aesthetic and the artwork. They’re thinking about how they’re going to perform these songs. This alleviates me from feeling that I have to come up with some sort of magic potion for them. All I have to do is hear the things they’re saying and the cues they’re giving me musically, and then develop ideas. Once you have that rapport with somebody, you don’t need to go to a million different places or have dozens of songwriters.”

Keeping It Real

As well as going to number one on the US and UK country charts and becoming a Top 10 hit on the album charts, Golden Hour also earned Musgrave, Tashian and Fitchuk two Grammy Awards, for Album of the Year and Best Country Album. The trio have since collaborated on Musgraves’ equally successful albums star‑crossed (2021) and Deeper Well (2024). Fitchuk also received Grammy nominations in 2021 (Best Country Album for Little Big Town’s Nightfall), and 2022 (Best Country Song for Musgraves’ song ‘camera roll’). Deeper Well is this year nominated for Best Country Album, and Fitchuk for Producer of the Year, Non‑Classical. Other achievements listed for this nomination are co‑writing and co‑producing albums by Stephen Sanchez (Angel Face) and Maggie Rogers (Don’t Forget Me), and songs by Beyoncé (‘Amen’), Still Woozy (‘Lemon’), Role Model (‘Oh Gemini’) and Leon Bridges (‘Peaceful Place’), and producing Musgraves’ version of ‘Three Little Birds’ and Leon Bridges’ rendition of ‘Redemption Song’ for the Grammy‑nominated soundtrack for Bob Marley: One Love — Music Inspired By The Film.

Golden Hour earned Musgraves, Tashian and Fitchuk two Grammy Awards, for Album of the Year and Best Country Album. The trio have since collaborated on Musgraves’ equally successful albums star‑crossed (2021) and Deeper Well (2024).

Golden Hour earned Musgraves, Tashian and Fitchuk two Grammy Awards, for Album of the Year and Best Country Album. The trio have since collaborated on Musgraves’ equally successful albums star‑crossed (2021) and Deeper Well (2024).

Despite very much not pigeonholing himself as working exclusively in country music, 25 years of living and working in Nashville have naturally informed Fitchuk’s approach. It shows, for example, in his preferences for working in a room with others.

“One of my favourite things about making music is the way that it connects me to other people. I’m not prolific on my own. I’ve always been most productive when I’m working with other people. So I met a lot of good role models, and musicians willing to share their experience and their knowledge. All you have to do is pay attention and listen and not think that you have it all figured out, and be brave enough to try things that are outside of your comfort zone. There have been plenty of times I’ve been called to write a song or to go play on something where I feel completely inadequate or that’s out of my wheelhouse. But I show up, and by nature of putting yourself in uncomfortable, stretching situations, you widen your net of experience.”

Also in keeping with Nashville’s modus operandi is Fitchuk’s preference for physical rather than virtual. However, instead of the band‑in‑the‑room session approach common in the town, Fitchuk likes to play many of the instruments himself.

“I love and respect the process of recording with a band in a room, and I have had a lot of experience being a session musician in those situations. However, it is less common for me to put a group of studio musicians together. That’s not because I don’t enjoy that. In fact, I miss the camaraderie. I think it’s a dying art, and I hope that I will have opportunities to do that. But before 2016, I already played many parts myself, because I couldn’t afford to pay other musicians. When I, during the writing process, hear what I want an instrument to do, it’s easier for me to put it down. A lot of the time, as the song is being written, I’m two feet away from a drum kit, and I just jump on. Later, if I think something is lacking, and I want somebody more specialised to come and replace it, I will arrange for that. But then I run into the artist saying, ‘Oh, no, no, no, we like what you did.’”

Talent Pool

Fitchuk’s playing credits include drums, percussion, piano, synths, vocals, acoustic and electric guitars, bass, and more. His DIY approach may be common, but the skill with which he plays many of these instruments, in addition to co‑writing and co‑producing, is not. It led to Fitchuk being nominated at the Academy Country Music Awards of 2019 for Producer of the Year, Drummer of the Year, Bass Player of the Year, Piano Keyboard Player of the Year and Specialty Instrumentalist of the Year. Fitchuk’s musical prowess has its roots in growing up in Chicago, and his early years in Nashville.

A true multi‑instrumentalist, Ian Fitchuk often plays nearly all the instruments on tracks that he produces.

A true multi‑instrumentalist, Ian Fitchuk often plays nearly all the instruments on tracks that he produces.

“Both my parents are classical musicians, and were very involved with their church. I sang in the church choir, and I played in high school bands, being a drummer in one, and a keyboard player in another. I also started songwriting. I moved to Belmont University in Nashville in 2000, because their commercial music programme was a hybrid of popular music, classical and jazz. That melting pot appealed to me, as did studying jazz piano with a particular professor there. So I didn’t grow up with country music, and didn’t move to Nashville for that reason.

“During the first two weeks I was at college I met some guys there who were in a band called the Dahlia Llamas, which had signed to MCA. They were not country, but more in a David Matthews Band direction. It was pop, but with jam band elements. They were finishing an album produced by Kenny Greenberg and Matt Rollings, and I recognised Matt’s name from liner notes of CDs that I had. Béla Fleck was also on the album. I was impressed, so I quit school to play keyboards and tour the world with them, opening for Béla Fleck, John Mayer and others.

“I enjoy travelling and music, but after one and a half years of touring I realised that the life of a touring musician was not for me. So I left the band. When in high school bands I had played keyboards and drums, and also had taught myself enough bass and guitar to make songs. So from about 2002 to about 2010 I did a lot of work in Nashville as a session player. Certain people would know me as a drummer, certain people knew me as a keyboard player, others knew me only as a bass player.

“During this session work I was on the floor with three or four other musicians, and I learned about whatever instrument I was playing, and I learned about what the other musicians were doing. So the next time I was playing that instrument, I was like, ‘OK, I noticed he used this bass,’ or ‘I noticed that the drummer avoided using cymbals the entire session, which really brought out the tonality of the drums,’ or ‘Wow, he played really light,’ or ‘This or that chord voicing on guitar.’ I had a front seat for really long.

“While working as a session player I also got to know some of the big producers in Nashville, like Jacquire King and Jason Lehning, and I learned about production and working in the studio. Also, a friend called Josh Moore was producing major‑label records in nice studios in Nashville, and I spent a lot of time watching what he was doing. I liked the way that everything came together in the studio, the pairing of musicians, the communication with artists, and so on, and went into production myself.

“I made a bedroom recording with an artist named Griffin House, using the first version of the Pro Tools HD on a rig a friend of mine had. We also had a Blue Kiwi microphone and a Focusrite pre, and that was about it. We made an EP with Griffin House that got picked up by Nettwerk Records, and this brought me out to LA and introduced me to more of the music business side of things. That’s when I realised that I could enjoy producing and putting albums together, even as I was only successful in the margins.”

Expert Help

At this point, Fitchuk’s story has arrived where this article started, at the end of his 10 years working as a producer and session musician outside the mainstream. Before Golden Hour, he recalls, he “wasn’t doing much songwriting, or part of the Nashville songwriting community”, but he has since contributed to many recordings as co‑songwriter, multi‑instrumentalist, and co‑producer. It’s a remarkable number of hats to wear, made easier by the fact that he leaves the engineering and mixing largely up to others. For this reason he does not have his own studio.

“As I mentioned, when I first started producing, I was working with a friend who had a Pro Tools HD rig, and was very capable as an engineer and handled the computer. I have learned Pro Tools and Logic enough to be able to get ideas down, but other than that I’ve kept my distance from the computer. I’ve always been around so many people who have amazing studios that I felt no need to have my own. I have thought about it, but I like the change of pace of going to different studios. If I had my own, I might get sick of it pretty quickly.

“I try to leave the tech details to the experts. I have worked with many engineers who day in and day out are obsessing over the nuances of the innumerable ways to make great recordings. I’m sure that some of the records that I produced in the early‑mid‑2000s could be ripped apart sonically, but there was still something that musically resonated with people that goes beyond the fidelity. We’re making music, right? There’s gonna be bleed. There’s gonna be imperfections. There’s going to be buzzing guitar lines. As long as that’s coming from a place of inspiration and not just lack of care, I think it’s OK.

“I know when something doesn’t sound good to me. I might even be able to tell you that it’s not the right mic, or to identify that it sounds over‑compressed. But with the engineers that I work with I don’t have to use language like that to explain what I’m hearing, or to translate what the artist wants to hear. I can be the middle man between musical language and more technical speak. I can describe things, like ‘We’re battling a high‑mid frequency here,’ or ‘She really doesn’t like the way that mic enhances the esses.’ I can facilitate those conversations and make people hear each other. I have my plate full already, thinking about the story that the song is telling, or managing the expectations of the A&R, or of management, or consoling the artists with whatever existential thing they’re going through. It’s all hands on deck. So when I find engineers who are really good at what they do, I let them do that.”

Plum Job

Songwriting sessions with Kacey Musgrave usually take place at Daniel Tashian’s studio. “Daniel has a studio called Royal Plum in his backyard. It’s a converted garage, which has everything you need: a drum kit, lots of guitars, lots of keyboards, a handful of great microphones, and a very cosy living room feeling. Daniel and I are very similar in that we both feel pretty confident on most rhythm instruments: piano, guitar, bass and drums. We also sometimes work at our friend Konrad Snyder’s studio, an engineer and mixer who I work with a lot.

“Kacey, Daniel and I sit with one or two guitars and/or a piano. She’ll come in with a handful of titles, and we write towards them. This is a common songwriting strategy in Nashville. It’s not only important to her to have a title that is interesting or sounds good, but also, how do you write towards it in a way that makes sense, and has an interesting journey? So we’re spinning around a concept or a title until we get a clear lyrical idea that we can latch onto, and from there it’s a matter of finding what matches that feeling musically. So we’re oldschool, where the song gets written around a piano or a guitar or both. It’s very rare that we write to a pre‑existing track.

“So the first step is writing songs, and we initially record them as little voice memos on the iPhone, making sure that we remember what we think is good. Typically towards the end of the day, we record a guitar/vocal. It’ll be really quick, just to make sure that we’ve preserved the idea. Kacey takes recording as seriously as she takes writing, so it’s pretty common that we get a final vocal the day that we’ve written the song. We may come back to and touch it up later, but in many cases her final vocals were recorded with a guide guitar with maybe some rhythmic element or a few textures, like piano or something else, that demonstrate the feeling and the aesthetic of the song.

“When we have one song that feels good, it gets the ball rolling, and then there’s the next, and so on and so forth. With Kacey, we do the backing track recordings later on. Most of the time we end up in commercial studios, whether Sound Emporium or Blackbird in Nashville, or Electric Lady in New York. Deeper Well was mostly recorded during multiple trips to Electric Lady.”

Unforgettable

Ian Fitchuk played most of the instruments on Maggie Rogers’ album Don’t Forget Me.Almost the whole of Maggie Rogers’ acclaimed album Don’t Forget Me was co‑written and co‑produced by Rogers and Fitchuk. The latter plays the vast majority of the instruments, and the album sounds like experimental, arrangement‑driven indie pop. “Deeper Well and Maggie’s album were mostly recorded in the same top‑floor room at Electric Lady. While we did some writing with Kacey in New York, almost all of Maggie’s album was written there during very rapid‑fire sessions. Maggie and I wrote the majority of the songs in a two‑ or three‑day span and I recorded most of what’s on the record during those first couple days.

Ian Fitchuk played most of the instruments on Maggie Rogers’ album Don’t Forget Me.Almost the whole of Maggie Rogers’ acclaimed album Don’t Forget Me was co‑written and co‑produced by Rogers and Fitchuk. The latter plays the vast majority of the instruments, and the album sounds like experimental, arrangement‑driven indie pop. “Deeper Well and Maggie’s album were mostly recorded in the same top‑floor room at Electric Lady. While we did some writing with Kacey in New York, almost all of Maggie’s album was written there during very rapid‑fire sessions. Maggie and I wrote the majority of the songs in a two‑ or three‑day span and I recorded most of what’s on the record during those first couple days.

“We had a creative exercise where she’d play a track from a legendary album, like Rumours or Thriller, or whatever. I would quickly play something that she would react to that immediately generated melodies and ideas. As soon as we had a chord structure that felt like a verse or a chorus, I would put it down on guitar. She would then go into another room to write her parts, while I fleshed the arrangement out, still not having heard the whole arc of the melody. Thirty or 45 minutes later, she’d get on the mic and sing. Two hours later, we’d be onto another song.

“At that point we were thinking, ‘Wow, these songs are coming really fast. Let’s come back in a few months to record them properly.’ We even discussed putting a band together to track the album in the old‑school way. We booked more time at Electric Lady a couple of months later and tried to replace and improve on what we had recorded. But the minute we tried that, the demos started to lose some of their identity. Every step forward felt like a step back.

Ian Fitchuk: A lot of the time, things that I think are just demos for the sake of getting the song written end up standing the test of time and being released.

“With many artists it’s common to be in the studio for the day with them and explore song ideas, and the moment something starts to catch, I’ll be putting things down as musical placeholders. By the time the song has been written and we later try to re‑record or perfect the demo, we realise that a lot what was meant to be replaced has a feeling that is hard to recreate afterwards. So a lot of the time, things that I think are just demos for the sake of getting the song written end up standing the test of time and being released.”

Keep It Natural

Fitchuk gets quite involved in post‑production processes, whether vocal production or rough mixing, but is happy to let go in the end, again happy to leave things to the experts. “With regards to vocals, I’d like to say that I like to capture the vocals while we’re going. I don’t like that moment when you have all the basic tracks recorded to scratch vocals, and then there’s this big pressured time when you need to get the final vocals. Instead I like to record the vocals while the arrangement is being fleshed out and the production created. The chains that we use are very interchangeable, but usually some beautiful mic like a Telefunken 251, a Neumann 47, or an AKG C12 or C24, but there are artists who love to hold a mic, which always leads to a Shure SM7.

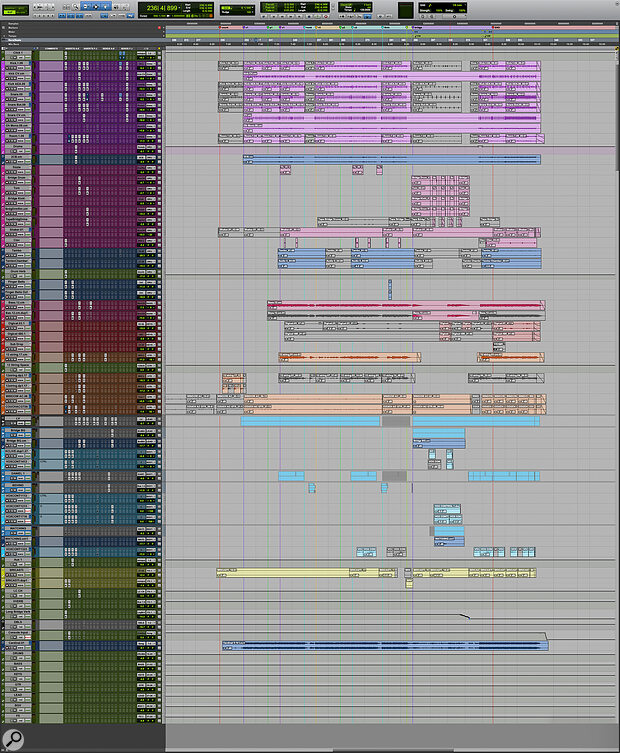

This composite Pro Tools screen shows the tracking session for Kacey Musgraves’ single ‘Cardinal’, engineered by Konrad Snyder.

This composite Pro Tools screen shows the tracking session for Kacey Musgraves’ single ‘Cardinal’, engineered by Konrad Snyder.

“Most of the artists I work with are performance‑based, and don’t need a lot of comping and editing later on. They also like to be involved in that final comping process. I don’t mind comping vocals, but I prefer for it to be a collaborative process. We do tune sometimes. I don’t like it when you can hear it, and it sounds like you’ve tried to make a not very good singer palatable. But when there’s an amazing performance that has a few notes that need massaging, I don’t see that as different to having a great guitar part and punching in a mistake or out‑of‑tune note. I prefer to do a punch in with a singer, but when we are using tuning, it’s mostly [Celemony] Melodyne, and maybe a little bit of Antares Auto‑Tune once in a while. I try to make it as musical as possible. I challenge anybody to point out sloppy tuning on the records that I make.

“As for adding reverb, I actually like the natural reverbs that both Sound Emporium and Blackbird have. There are a million great plug‑ins. All the UAD and Waves and Valhalla stuff is awesome, but for me it’s not as good as natural reverb. At Konrad Snyder’s studio, where we’ve recorded a lot, he has a kitchen outside of the control room with a great ambience. I love it when you can achieve dimension and space with the actual sound of the room you’re recording in. It’s also why I like recording in different studios. I’ve been at Echo Mountain Recording in Asheville, and Muscle Shoals, and EastWest. With all these different studios, and even the regular houses that I’ve recorded in, using the room you record in as much as possible as an instrument is more exciting to me than a one‑size‑fits‑all plug‑in.”

Letting Go

Many of the tracks and albums (co‑)produced by Fitchuk are mixed by Shawn Everett or Konrad Snyder. “I never hand things off to a mixer scared that they’re going to destroy it,” Fitchuk comments. “I’m always excited to hear where they take it and to hear risks, to hear musical decisions that go beyond just trying to preserve what’s already there. That to me is a big part of post‑production. Sometimes you want a mixer that’s just going to lightly touch what’s there. But I like taking a plunge into the deep end and hearing things done by a mixer that take the music that you’ve been kind of obsessing over to a different place. It’s nice to have somebody shake that up a little bit and challenge what you thought you were doing and blast it out and exaggerate it in some ways.

“I love a lot of modern music, and also pop music that has been scrubbed and tightened and tweaked to every little detail. From time to time I will employ some of those techniques in my own way. I don’t like things to be messy or dirty just for the sake of it. I think things can feel good if they’re really tight and really organised. I also think things can feel good if they’re a little dishevelled. It’s really about what emotion you’re trying to convey.”

Beyoncé

Ian Fitchuk was involved as a writer and producer in ‘Amen’, the last track of Beyoncé’s 2024 Cowboy Carter album, along with other writers and producers including Dave Hamelin, Danielle Balbuena (070 Shake), Tyler Johnson, Cameron Ochs (Cam), Derek Dixie, Darius Scott and Sean Solymar.

“In 2022, a handful of Beyoncé’s writers, Hamelin, Dixon and INK, came to Nashville, and invited me for a week of sessions. They already had several songs for the album, but were pretty secretive about it. All I was told was that Beyoncé was playing with country music, but to hold that concept pretty lightly.

“One day a songwriter called Cam was in the studio with us. She brought in the song ‘Ameriican Requiem’ that she had already worked on with Tyler Johnson. She played it for Dave Hamelin, Darius Scott, Derek Dixie and I. There also was an idea for ‘Amen’, with a loop made by Dave and producer 070 Shake. ‘Amen’ and the idea for ‘Ameriican Requiem’ were totally separate, but that day we messed around with conjoining those two ideas into one piece.

“In the middle of all that, I was on piano and framed some of the chords that were already in place in a different way. I left after a week or so, having contributed to eight or nine pieces, with no idea what was going to happen with them. I didn’t hear much about it for almost two years. A couple days before the album came out, I was notified that the song was going to be used, which was exciting news. The whole thing was pretty unusual for me.”

Konrad Snyder: Nashville Tracking

Konrad Snyder.Ian Fitchuk regularly works with Nashville engineer, mixer and producer Konrad Snyder. Snyder has an engineering credit on all but one track on Deeper Well, and mixed 11 of the 21 songs of the extended version. He elaborates on some tech details for two of the album’s singles, ‘Cardinal’ and ‘The Architect’.

Konrad Snyder.Ian Fitchuk regularly works with Nashville engineer, mixer and producer Konrad Snyder. Snyder has an engineering credit on all but one track on Deeper Well, and mixed 11 of the 21 songs of the extended version. He elaborates on some tech details for two of the album’s singles, ‘Cardinal’ and ‘The Architect’.

“On ‘The Architect’. Todd Lombardo engineered his own guitars. He used a combo of a Neumann U67 mic and a Coles mic. In the mix we ended up favouring the 67, and we compressed with the [UREI] LA‑3A. Kacey’s vocals were also recorded with a 67, through an older Brent Averill 1084 and then through an Undertone Audio Unfairchild. The reverb of choice was the Bricasti. The piano in the song is a Yamaha upright recorded with the new Neumann M49 reissues, going through the Rupert Neve Shelford, and again the Unfairchild. The banjo was recorded through a Neumann M49, the Shelford, an 1176 and the Echofix EFX3 chorus echo.

“On ‘Cardinal’ I used an AKG D12 on the kick, a [Shure] Unidyne 545 on the snare, an SM57 on the snare bottom, the EV RE11 for the toms, Neumann KM56 for overheads, and Coles 4038 for the room sound. All mics went through the Inward Connections MP820 mic pres, bused into an 1178. For the bridge we sent the drums into an Otari 5050 and shifted it to half speed to take them down an octave.

“The hammered dulcimer was recorded with a Neumann KM56, going through the MP820 and a [UREI] 1176 Rev D. The acoustic guitars went through a AKG D19, going into the MP820, 1176 Rev D, and [Studer] J37 tape. Blackbird actually got a J37 a week before we came in. And it was a one‑inch two‑track. It sounded unbelievable. We took some time while we were there and ran a lot of what we recorded at other places through their gear. The bass went directly into the MP820, and I also used a vintage [Teletronix] LA‑2A. Kacey’s vocals were recorded with an AKG C24, Neve 1084, Heritage Audio Motorcity EQ, and the Unfairchild. The reverbs were a mixture of an EMT 240 plate and a Bricasti M7.”