For Jack White, analogue recording is not about looking back to the past, but choosing the ideal medium for his art.

“I think I was born in the wrong generation,” proclaims Jack White. “I am definitely somebody who is not supposed to be in this time period. I probably should have been around in the 1800s, or 1930s. I am a lost soul in this time period, with the Internet, with digital technology and so on. This is not my place to be. But I am finding my place in all of it and am making it work for me. Third Man Records releases everything on vinyl as well as on digital. We spend 50 percent of our energy on the Internet presenting what we put out in the digital format. I live in that world, whether I like it or not. The great thing for me is that I get to craft things the way I want them to sound.”

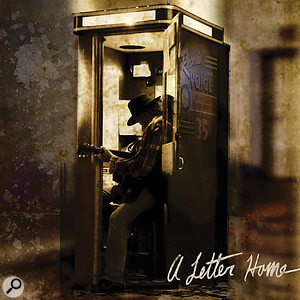

Photo: Mary Ellen MatthewsSongwriter, artist, producer, guitarist and singer, White is also owner of Third Man Records and Third Man Studios, and a board member of the Library of Congress’s National Recording Preservation Foundation, an organisation to which he last year donated $200,000. The titles of White’s solo albums, Blunderbuss (2012) and Lazaretto (2014) exemplify White’s love of bygone days — the former is an 18th–century firearm and the latter a quarantine station for maritime travellers. But for a man who feels so out of place in the modern era, Jack White is remarkably successful at “making it work” for him. Lazaretto has topped the charts in many countries around the world, selling a whopping 40,000 vinyl copies in one week in the US, and for most of 2014 he’s been playing sell–out shows in major venues around the planet — until recently he had two backing bands, one all–male and one all–female. He also finds time to produce much of Third Man’s output, most recently Neil Young’s album A Letter Home, which was recorded on a 1947 Voice–O–Graph vinyl recording booth and is surely the most lo–fi charting release of the last 50 years.

Photo: Mary Ellen MatthewsSongwriter, artist, producer, guitarist and singer, White is also owner of Third Man Records and Third Man Studios, and a board member of the Library of Congress’s National Recording Preservation Foundation, an organisation to which he last year donated $200,000. The titles of White’s solo albums, Blunderbuss (2012) and Lazaretto (2014) exemplify White’s love of bygone days — the former is an 18th–century firearm and the latter a quarantine station for maritime travellers. But for a man who feels so out of place in the modern era, Jack White is remarkably successful at “making it work” for him. Lazaretto has topped the charts in many countries around the world, selling a whopping 40,000 vinyl copies in one week in the US, and for most of 2014 he’s been playing sell–out shows in major venues around the planet — until recently he had two backing bands, one all–male and one all–female. He also finds time to produce much of Third Man’s output, most recently Neil Young’s album A Letter Home, which was recorded on a 1947 Voice–O–Graph vinyl recording booth and is surely the most lo–fi charting release of the last 50 years.

Aiming For Soul

“Analogue is the medium of all the kinds of music that I am really fond of,” comments White. “Form follows function. You have to ask yourself what you are trying to accomplish. What are you trying to make it sound like? When you are recording and producing, you are aiming for something and if you want vibe, warmth, soulfulness, things like that, you will always be drawn back to analogue. I was shocked by how many people were upset by the Neil Young record, because it sounded scratchy and lo–fi. But they completely missed the point, which was that we were obfuscating beauty on purpose to get to a different place, a different mood. European artists used to talk in the cafés in France about the mediums that they were using, whether oil or watercolours or what type of canvas is the best for what purpose. It’s normal as an artist to talk about craft and the beauty in how things are done, but a lot of musicians don’t really seem to care about the recording medium. They don’t care about the advantages and disadvantages and different vibes that you can achieve. They just think that if other people use Pro Tools, they should use it too, and that’s it.

“However, the actual sound of analogue is 10 times better than that of digital. I think the reason why many people say they don’t like the way things sound on the radio or the television nowadays is because it’s all recorded digitally. Having said that, it’s not really digital recording as such that’s the problem. A band playing live in a room recorded straight into Pro Tools doesn’t sound bad. The problem is the multitude of plug–ins and clicks that are applied to the Pro Tools recording after that. In the analogue world you just don’t do all that stuff. You don’t mess with the recording that much. Because it’s on tape, you tend to leave it alone. But when it’s in Pro Tools, people keep clicking and editing and removing pops and buzzes and they place the drums on a grid to get it in perfect timing. All those moves just suck the soul and life out of a song.

“On top, most of these digital plug–ins are emulations of the real thing. ‘Digital reverb’ is the most ironic phrase you can come up with. It doesn’t make sense, because reverb is a natural, real thing. It needs springs, or a cave, to be there in real life. A plug–in emulation of that may sound OK to many people, but when you pile several emulations on top of each other, with nothing natural in it, you don’t get results that are very interesting. You can use these things to your advantage, of course. The new Kanye West album is obviously recorded on Pro Tools but sounds unbelievable, because it is very simple and there aren’t a lot of components going on, and this really allows the songs to shine. Plus he mixed using analogue components. Bands like Daft Punk and Queens Of The Stone Age also know what sounds best for what they are trying to accomplish. I really admire their production techniques. QOTSA probably record digitally, but they get a really good tone, using analogue amplifiers and so on.”

Another essential aspect of White’s approach is the way he cherishes hard work and refuses to take the easy way. Asked whether his previous career as an upholsterer plays a part in his adoration of the no–pain–no–gain principle, he replies, “There’s no doubt that I can definitely relate to anyone who works in any kind of craft or trade where they get their hands dirty, whether it is a carpenter or a plasterer. My dad always pointed out when people made something look easy, whereas in fact what they were doing was really difficult. I put this on myself all the time: I need to make the process very difficult so that when it sounds good at the end, I know I can be proud of it. I know it wasn’t auto–tuned, and the drums weren’t put on a grid and I didn’t spend hours correcting ‘mistakes’. A lot of making music is dirty work, where you are getting in there, and in my case I have to pull things from nowhere, and on top of that there’s the presentation of it, the packaging, how it is presented to people. I have to think about those concepts as well. They become my challenges, and I create them for myself, and that is where I start to feel inspired.”

Eight Plus Eight

Jack White’s Third Man Records organisation encompasses a variety of business activities, including his own recording studio.

Jack White’s Third Man Records organisation encompasses a variety of business activities, including his own recording studio.

However, White is not a Luddite, and he is not at all averse to using modern technology when it suits him. He drives around in a state–of–the–art black Tesla Model S electric sports car, which, as his engineer Joshua Smith apparently once pointed out to him, is one of the most digital cars ever invented. According to Smith, his boss replied that he’s never objected to using the latest technology in principle. Moreover, White uses the car’s top–of–the–range stereo system as one of his main monitoring references when judging mixes, having them beamed to him via an FM radio transmitter. Similarly, while the no–pain–no–gain principle is one of the reasons why most of Blunderbuss and some parts of Lazaretto were recorded to eight–track analogue tape, White’s pragmatism means that he had no issues using Pro Tools when necessary. He simply notes: “I have never recorded to Pro Tools or mixed in Pro Tools, but it is great for doing edits that you can’t do with analogue tape.”

All of Lazaretto was recorded to one or, usually, two of Third Man Studio’s Studer A800 two–inch machines, which have John French’s JFR Magnetic Science’s Ultimate Analogue eight–track headstacks with a proprietary ninth timecode track for link–up, which allows the two eight–track machines to be combined for 16–track recording. In addition, while Pro Tools was barely used in the making of Blunderbuss, it saw extensive mileage during the making of Lazaretto.

White went on record a few years ago stating that he couldn’t see himself ever making a solo album, and both Blunderbuss and Lazaretto appear to have come into being more or less by accident. Blunderbuss started as a by–product of sessions White had organised for an artist who didn’t show, so he decided to record some of his own songs with the musicians who turned up at his studio. Lazaretto came into being in a similarly sideways fashion

“When I did Blunderbuss we did a lot of songs that I never finished, and there were also some ideas that I put down that maybe could have been used for the soundtrack for The Lone Ranger [a 2013 Disney action movie featuring Johnny Depp]. I never wrote anything specific for that project anyway, but it did lead me to go in and record some ideas for some instrumentals that I had. I also wanted to record both my female and male bands while we were on tour and really cooking. If we’d waited until after the tour and with everyone having been home for six weeks or so there would have been a different vibe. So I wrote many things specifically for those recording sessions during the Blunderbuss tour, to give us something to play. These recordings usually were unfinished, so it was a matter of ‘OK, I’ll get back to this way later, maybe in six months or so when we’ll be finished touring.’

“As a result I had all these songs sitting around that were half–finished, a quarter finished, three–quarters finished, often without vocals. There were about 25 of them, which was a place I’d never been in before in my career. I’d never had that luxury, or that problem, and I considered it a problem, because I’d never written vocals for music that had been sitting around for that long. I’ve never had a problem writing music, I’ve never had writer’s block, but I did have a problem writing vocals for my own music. That was a strange thing for me to do. I had never separated the two processes, of writing music and writing vocals, over such a big distance, and I had to come up with some tricks to overcome that.”

One “trick” that White employed was reworking some short stories and plays that he’d written when he was 19. It was the need to overdub his vocals, and often his guitar parts as well, that led to changes in song structures and arrangements which prompted many of the Pro Tools edits. White explains: “A song like ‘Would You Fight For My Love?’, for example, had three major edits, from takes of two different bands playing at three different times. We edited the tape to punch the male band over the female band in the chorus, with all eight tracks, and this was a very dangerous move, but it turned out amazing. But many other edits were so complicated that we had to put the material into Pro Tools, do the edits, and then we transported it back to tape again after that.”

A Bunch Of Stuff

One person who has played a central role in helping White put Third Man Studios together and who has manned the controls for many years is Vance Powell. The engineer, mixer and producer worked as chief engineer at Blackbird Studios in Nashville from 2001–10, and in 2006 also set up his own facility, Sputnik Sound, together with Mitch Dane. Powell met White for the first time in 2006, when he worked on Dangermouse and Daniel Luppi’s Rome album, on which White guested. The year following White asked Powell to mix the Spanish–language version of the White Stripes Vance Powell at Sputnik Studios. song ‘Conquest’ and a regular collaboration was born, with Powell since 2009 dividing his time between Third Man Studios and Sputnik. Recently, however, Powell has become increasingly busy at Sputnik: “I think I did 37 albums last year!” Because White tends to only give a few days’, or even a few hours’ notice when he wants to go into the studio, Powell’s former assistant, Joshua V Smith, has increasingly taken over at Third Man, and is credited with recording most of and mixing all of Lazaretto.

Vance Powell at Sputnik Studios. song ‘Conquest’ and a regular collaboration was born, with Powell since 2009 dividing his time between Third Man Studios and Sputnik. Recently, however, Powell has become increasingly busy at Sputnik: “I think I did 37 albums last year!” Because White tends to only give a few days’, or even a few hours’ notice when he wants to go into the studio, Powell’s former assistant, Joshua V Smith, has increasingly taken over at Third Man, and is credited with recording most of and mixing all of Lazaretto.

However, Powell conducted the first sessions for Lazaretto, in 2012, with Smith still assisting. “We recorded a bunch of stuff for Jack that we weren’t sure what it was for,” Powell recalls. “The last sessions I recorded for Lazaretto were in December 2012: three days with the guy band and three days with the girl band. The basic tracks were cut live in the studio, and then there were overdubs, like the harmonica solo in ‘Three Women’, and many of Jack’s vocals, which were recorded by Josh. We recorded to tape, initially just eight–track, to RMG 900 at 7.5ips. Jack loves that sound and we also are very happy with the quality. It has a hefty bass bump, almost an octave lower than 15ips, and the top end is flat until 20k. Something happens at the top end, above 4k, with tape compression; the sound is easier saturated and it meant that we never had to worry about things like de–essers. We did not hit the tape hard. In fact, we left tons of headroom, because it retains transients better.

“The signal chains remained pretty much the same throughout the recordings. There isn’t a big console or a lot of gear at Third Man, though Jack acquired this really cool, all–tube UA 1008 desk, which dates from a later date than the 610. It was made for film and has nine mic inputs and three film inputs. The desk lives out on the floor close to the keyboards. I’d have a Sennheiser MD421 or Shure SM57 or maybe a ribbon like an AEA R92 on the organ, a Neumann stereo SM2 on the piano, and they went into the 1008, which came up on the main Neve desk as a pair of channels or just one channel. I probably had a Fairchild on the keyboards, and maybe a Neve 2254 compressor on the desk. The studio’s 1960s Ludwig drum kit had an AKG D12 on the kick, a Shure SM57 on the snare top and bottom, Sennheiser MD421 on the toms, and I think I had a Neumann U67 for mono overheads. The drum mics all came in on the Neve desk, and I probably had an 1176 on the snare and maybe also the kick, or a Fairchild 670. We normally record the drums to one track, plus we’ll have a kick drum track to have more control over that. I don’t need stereo drums. For me, drums are right in front of me.

“On Blunderbuss I also used the Neve 33609 and RCA BA6A and an Ampex MX35 four–channel tube mixer to record the drums, but these sessions happened so quickly that I did not have a lot of time to set things up. There was not a lot of upright bass this time, but when there was one, I’d use an RCA 44 and something higher up like the RCA BK5A [cardioid ribbon mic]. There was an African drum on ‘Would You Fight For My Love?’, which had an AEA R92, electric bass would have been DI and a Neumann U67 on the amp, with maybe some compression from the [Fairchild] 670. I recorded Jack’s acoustic guitar with an RCA 77DX, and his electric almost always goes through his 1963 Fender Vibroverb in front of which I placed a U67, which went into the Neve 1073 desk and then straight to tape. I did not record any of Jack’s vocals, other than on the song ‘Just One Drink’ because that was done entirely live. I used a Shure SM57 or 58 on his vocals for that, and Josh recorded the backing vocals.”

Easter Everywhere

Joshua V Smith, the man who gradually took over from Powell at Third Man Studio as the latter became increasingly busy with other projects, is originally from Kernersville, a small town in North Carolina. During his high–school years he played in bands and developed an interest in recording, and discovered to his complete surprise that there was a unique, top studio in his home town: Fidelitorium Recordings, owned and run by Mitch Easter, who worked on REM’s early albums. Fidelitorium is chock–a–block with vintage and analogue gear, and observing and assisting Easter for a number of years, on and off, awakened a love of analogue gear and working methods in Smith. He moved to Nashville in 2006, where he became an assistant at Sputnik, first under Mitch Dane and then Vance Powell. He eventually ended up moving to Third Man, where he now works full–time. When White is on tour, Smith also acts as one of the singer’s stage techs.  Joshua V Smith (left, with Jack White) is not only resident engineer at Third Man, but also White’s stage tech.Photo: David James Swanson

Joshua V Smith (left, with Jack White) is not only resident engineer at Third Man, but also White’s stage tech.Photo: David James Swanson

Smith echoes Powell in explaining that the recording sessions for Lazaretto happened very quickly and often unexpectedly, with barely any time to set up. “There have been many situations where I’ve sat in Third Man and had no idea where we were going. But Jack always seems to know, so a lot of the time I simply hold on and enjoy the ride! I was second engineer on Blunderbuss, which was done fairly quickly, with most of the songs recorded in one piece. This new album felt much more pieced–together from different sessions. Jack will sometimes bring in a demo recording and play it for the musicians, but more often he simply starts playing on guitar or piano and the musicians just jump in. There are people who like to rehearse a song and really develop it, which technically could make for a better performance, but Jack doesn’t do it like that. In my observation he likes to capture the energy of people figuring it out, even if it’s not going to be perfect. In that sense he almost has a jazz mentality, in that he wants spontaneity and a kind of innocence in the way people are playing, and in the people engineering.

“I can get very detailed about things and get carried away by that, but Jack is very quick and will not allow us to get stuck in that kind of detail. If something isn’t working, sure, we try to troubleshoot it, but most of the time you have to, as Vance calls it, ‘spin to win’. You just have to push up the faders and hope that it’ll work; rarely do you get more than a few seconds to check the tones and the levels of the instruments. There have been many times when Vance and I were recording at Third Man, and we’d think it’s just a preliminary pass of a song, with the band just learning it, and we’re sure there’ll be another take, allowing us to sort out some technical issues. And then suddenly Jack will say, ‘OK, that’s cool, let’s listen to that.’ And I’m going, ‘Aargh, what am I going to do about that floor tom that I flipped the phase on mid–take?’ It definitely made for tricky mixing sometimes, when I had to figure out ways around these issues. They weren’t necessarily fixes, but more ways of covering something up so it doesn’t sound like an issue any more.”

Important Pieces

Predictably, given the Spartan approach to gear at Third Man and the fact that Smith learned his trade under Powell, the signal chains Smith used were very similar to Powell’s. There were a number of differences, though, as Smith explains. “Most of the band tracking sessions were recorded to eight–track tape, and we tried to keep it on eight–track, but with almost all songs there were overdubs and the amount of tracks got out of hand. Because we didn’t always want to bounce things, we went to 16–track by sync’ing the second eight–track. The signal chains remained largely the same for all sessions, and certain pieces of gear were important throughout. In addition to the D12 I’d also have a Neumann FET47 on the kick sometimes, particularly when I had the D12 on the floor tom. It’s also not unusual for us to have the Coles 4038 or Sennheiser 421 on the floor tom. I love the AEA R88 [stereo ribbon] mic, which we usually have above the kit, since it really helps capture the kit as a whole, but for these sessions it was usually down at Third Man Records, for recording the high–school bands that come in. I mainly used the U67 as a mono overhead for this record. The kit was always tracked in mono, but sometimes also with a separate Fulltone Tube Tape Echo drum track. At times we used the Fulltone to create polyrhythms that inspired other parts of the songs.

“I recorded Jack’s vocals mainly with a Shure SM57. Sometimes we used a Neumann U47, as well as an RCA 77D and a Shure SM7, and I often pushed his vocals hard through an 1176, which can make it difficult to keep the sibilance under control. But he likes that slammed vocal sound, and we used it quite a lot on this record. Jack also loves to amp his vocals. We’ll split the mic signal, and have one line going clean to the console, and the other going to an old tube amp, then back to the console. Sometimes we used amps with reverb, sometimes we didn’t, but overall we liked that biting mid–range sound from the amp on his vocals. Very rarely I recorded the clean and amped vocals on separate tracks and would then balance them later in the mix, but usually we just summed them to one track.

“I tend to like an RCA BK5B on Jack’s acoustic guitar, and occasionally an RCA 77, or an SM57 if everything else in the room was pretty loud. He mostly played an old Gibson Army Navy or his custom Gretsch Round–Up ‘Claudette’. The Army Navy doesn’t sound like a modern acoustic. It has a very punchy and boxy sound, without much resonance, so the things I’d normally use on an acoustic don’t always work. The mic would go into the 1073, usually with a bit of 1176 compression. I miked Jack’s electric guitar amp — often his 1964 Vibroverb — with a U67 and also a Shure SM57, and we sum them on the desk to one track. Sometimes I’d only have the 57 on his amp.”

Pieced Together

As White explained above, Powell and Smith edited the recordings on both tape and in Pro Tools to get the desired final song arrangements and structures. Smith highlights two songs on the album as being indicative of two different approaches: the title track and the epic ‘Would You Fight For My Love?’ He recalls: “We have a small native Pro Tools system at Third Man, with 16 inputs. We initially bought it for tape backups, just to have digital backups, but when we had some very complicated edits to do, it became more of a creative tool. But it always ends up going back to tape. ‘Lazaretto’ and also ‘Three Women’ definitely were band tracks done in one take, and they also were done on the same day, so they have very similar sounds. They were fairly straightforward to record and mix, and had no major edits. On the other hand, ‘Would You Fight For My Love?’ was one of the most difficult tracks to do, because it consisted of three different sections edited together. The intro was the guy band, the quieter section with the toms is the girls, and then it’s back to the guy band where the hi–hat comes in. These edits were done by Vance on tape, and I did several additional edits in Pro Tools later on. That song was one of those that were pieced together from bits that were not originally intended to be together, or so it seemed to me. We considered re–recording the song, but Jack liked the tones and the vibe and did not want to redo it.”

Smith and White explain how they went about mixing the album together, with a particular focus on their mix of ‘Would You Fight For My Love?’

“I have always mixed all my albums,” says White, “but I don’t like to turn the knobs. When several people turn knobs at the same time, it’s not a good thing. So I basically direct the entire mix, everything about it: what compression to put on the kick drum, what kind of reverb is going on the snare, the effects on the vocals, and so on. Every single mix choice is mine, but again, I don’t touch the knobs. That feels more comfortable to me. At earlier occasions I sat down with the person and we mixed together and that just doesn’t work. It’s like two people playing the guitar at the same time. But it does work when I direct all components of the mix. I have always worked like that, with every engineer.”

“Yeah, Jack is very much part of the mix process,” agrees Smith. “I generally will set something up that I feel is a good start, maybe in the evening, and he then will come in the next morning and do automation passes. He can be very hands–on. Before we had Flying Faders on the desk, everybody had to push faders around, but that’s no longer necessary. I assumed Vance was going to mix the album, but I think it didn’t fit with his schedule, and one day Jack came in and said, ‘OK, let’s mix this song.’ We then mixed the entire album in one stretch, doing pretty much one song a day, or one every two days, and then we went back and did several recalls. I have worked with Vance and Jack long enough to generally know what they like and don’t like, but Jack would sometimes throw me curveballs or wanted to go in a totally different direction with a song than I had imagined.

“A few of the songs were quite tough to mix, like ‘That Black Bat Liquorice’, ‘Just One Drink’ and ‘Would You Fight For My Love?’ Songs that were kind of pieced together from different takes might have up to five instruments on one tape track, which is where automation helped a lot. ‘Just One Drink’ is kind of a straightforward rock song. We did an early rough mix, that I ran through a Waves MaxxBCL, which we use to ‘heat’ our mixes, and Jack fell in love with it. He didn’t really want it that heavy, he wanted to mix and master with as little compression as possible, but with that song it was really hard to beat the rough mix he was so used to. With ‘Black Bat Liquorice’ I had messed around in the computer with bit–crusher and stereo widener plug–ins on the drums in certain breaks in the song, where the drums sound wide and distorted. It’s the only time I did an effect in Pro Tools for the entire album. I did it for fun, but Jack liked it and asked me whether we could do it in analogue. I was like, ‘Not really,’ so I printed the effect to tape and we kept it.

“The mix of ‘Would You Fight For My Love?’ was challenging because the two bands that were stuck together meant that I had to find a place in the middle that worked for the sounds of both bands. Luckily the recordings were similar enough, so I didn’t have to EQ them completely separately; I just had to find treatments that worked for everything. The dynamics of the song also were quite drastic. Trying to get all that to sit well was tricky. I had a Neve 33609 and also the GML 8200 EQ on the mono drum track. I will generally do my initial EQ on the Neve desk, but the 8200 is unbelievable for notching out specific frequencies — I also found the Inward Connections Brat EQ to be very handy in this department as well. I also like using the Drawmer DS201 dual gate, to bring out a little bit more of the snare or the kick in the mix. We also had the second drums echo track with the Fulltone in this song.

“I didn’t compress the bass any further, and maybe just used some Neve 1073 desk EQ. I used the Dbx 500 [Subharmonic Synthesizer] in this song, as well as several others. Jack loves it, but without having a sub in the studio, it can be an easy way to blow out your woofers! I didn’t have compression on the guitars either, again just some desk EQ. It was the same with the keys. For Jack’s vocals I again used the 1176 to give it a more upfront and smashed sound. He did a vocal double that I ran through a Neve 2254 compressor, plus there was an amped vocal track. You can hear this track after the bass break. I also used some Master Room reverb on the drums, the vocals, and the fiddle, as well as some Moog 500 Series delay in places. The only real delays we used on the album came from the Moog 500 Series, the Roland RE301 and the Fulltone Tape Echo. Jack doesn’t like a lot of reverb, so I had to use it sparingly, just as a little bit of glue: something that you pick up subconsciously, but don’t really hear most of the time.

“Finally, I ran the band, without the drums, through a separate desk bus for parallel compression from the API 2500. I did this to bring out a bit more of the stereo image, because the drums are in mono and in the centre, and I wanted the band to sound more cohesive. We normally have the API 2500 on our mix bus, but Jack wanted something different in this case, which freed up the 2500. We instead used a couple of Neve 2254s on the mix bus for this song. “

Ultra Vinyl

White and Smith mixed to a Mike Spitz custom–built Ampex ATR102 one–inch tape recorder, at 15ips. White likes to use his Tesla electric car as a mix reference, which, oddly, created some effects that won’t work as well in countries with right–hand–drive cars. “The Tesla sound system is Jack’s mix reference now, it’s what he’s used to listening to,” explains Smith. “We broadcast mixes to his car via an FM transmitter, and if we wanted higher fidelity we’d use a USB stick with 96k WAV files. We have a set of walkie–talkies and if he heard something in his car that he wanted turned up or down, he’d communicate with me via that. One of the interesting things is that Jack likes to mix from a driver perspective: he usually likes drums or vocal delays on the right because it creates a cool effect when he’s listening to it in the car.”

Finally, and entirely unsurprisingly, White takes a dim view of the loudness wars. When mastering engineer Bob Ludwig, in the process of mastering Blunderbuss, asked two years ago “Why don’t we just turn the gain up and not put any compression on it?” White’s response was, “I have been asking that fucking question for 10 years and nobody ever said that we could do that! So yes please!” Two years later White has taken a more nuanced approach. He’s pulled out all the stops for the Ultra–LP vinyl version, which includes two hidden tracks behind the centre labels, one side that plays from the inside out, dual–groove technology that creates two different intros for ‘Just One Drink’ depending on where the needle is dropped, and hand–etched holograms of angels that only show when playing the album with a light source directly above it, and more.

“I was planning to do exactly the same as with Blunderbuss,” explained White, “and I talked with Bob about this. But then the Ultra–LP project took shape and I wanted to make that its own beast, different from the digital version. So I decided on no compression on the vinyl version. Bob just turned up the gain on the master for the vinyl edition. We did have some mastering compression on the digital version, but without limiting or clipping.”

For someone who does not feel like a man of his time, Jack White III has a remarkable grasp of the things that work, and don’t work, in this day and age.

Third Man Studios

For many years, Jack White resisted the idea of setting up his own studio, preferring the time limitations associated with traditional studio work. Many of the White Stripes’ studio albums were recorded very quickly: in the case of White Blood Cells (2001), in as little as four days. But in 2009, after establishing a physical location for Third Man Records in Nashville, White decided to also build a studio there. Jack White’s love of primary colours even extends to his studio track sheets (this one is taken from ‘Hypocritical Kiss’ from Blunderbuss). The physically small facility contains a 16–channel, 1073–based Neve console originally from SABC in Johannesburg which also has four Neve 2054 compressor modules, with labelling still in Afrikaans, plus the two above–mentioned Studer A800 tape recorders, an Ampex ATR102 one–inch recorder, and a choice selection of mics and outboard. The latter includes Urei 1176, Teletronix LA2A, API 2500, Fairchild and Neve 33609 compressors, GML 8200 and API 550 EQs, and reverbs, delays and echos from Fulltone, Master Room, Moog, Roland, Furman and EMT.

Jack White’s love of primary colours even extends to his studio track sheets (this one is taken from ‘Hypocritical Kiss’ from Blunderbuss). The physically small facility contains a 16–channel, 1073–based Neve console originally from SABC in Johannesburg which also has four Neve 2054 compressor modules, with labelling still in Afrikaans, plus the two above–mentioned Studer A800 tape recorders, an Ampex ATR102 one–inch recorder, and a choice selection of mics and outboard. The latter includes Urei 1176, Teletronix LA2A, API 2500, Fairchild and Neve 33609 compressors, GML 8200 and API 550 EQs, and reverbs, delays and echos from Fulltone, Master Room, Moog, Roland, Furman and EMT.

“10 years ago I did not care about equipment names and numbers,” White elaborates. “I just liked the concepts. I liked analogue compressors, ribbon mics, and so on, and I did not care whether the ribbon mic was an RCA 77 or a 44. The first album by the Raconteurs, Broken Boy Soldiers (2006) and the White Stripes’ Get Behind Me Satan album (2005) were both recorded using nothing but a Coles [4038] ribbon microphone. That was my concept: ‘I like this mic, let’s use it for everything.’ The engineers said, ‘this is really hard to do, I have to EQ the hell out of everything to get a certain sound, why not use a 57 or something?’ but I said, ‘I don’t care because it gets us to a place where we wouldn’t have gotten if we’d used different microphones.’ We would have gotten a totally different vibe and mood if we’d done that. But when I decided to have my own studio I became incredibly involved in choosing the equipment, and I’ve slowly been collecting things that I’ve used over the years and that I thought sounded great. The studio also is very small, so that the musicians are pushed close together. Sometimes in a big studio, the drummer may be 40 feet away from the bass player, each with baffles around them, and the result is that they’re not really playing together. I wanted everyone in everyone else’s face, working closely together.”

Recording Neil Young’s A Letter Home

“Some people get caught up in emulating albums or artists from the past, and trying to make what they are doing sound exactly the same. I have never done that. I have never tried to make something sound like a record from 1962,” says Jack White, and his music certainly is forward– as much as backward–looking. There is, arguably, one exception in his oeuvre, which is Neil Young’s recent album A Letter Home. Recorded at Third Man, A Letter Home is marked down as Young’s 34th ‘studio album’, but it barely deserves to be called this, because it was not recorded in a studio but in a Voice–O–Graph.  Jack White’s Voice–O–Graph was painstakingly restored by Joshua Smith and Kevin Carrico.Photo: Jo McCaughey

Jack White’s Voice–O–Graph was painstakingly restored by Joshua Smith and Kevin Carrico.Photo: Jo McCaughey

Also called the ‘Third Man Recording Booth’, the Voice–O–Graph looks very much like a telephone booth from the outside, and it was widely in use in the US from the 1940s to the 1960s. The coin–operated machine allowed people to record up to two minutes of extremely lo–fi audio, full of crackles, scratches and wow–and–flutter, onto a six–inch phonograph disc. White says that he’d been “looking for one for 15 years” and he finally managed to acquire a Voice–O–Graph a couple of years ago. “We spent a year and half restoring it and getting it in tiptop shape. It sounds really incredible now. People used it to send audio letters to each other. People in the army, in wars, sending messages home, it was pretty amazing.”

The Third Man Recording Booth was officially opened on April 20th, 2013, and the Third Man web site states that it is “the only machine of its kind in the world that is both operational and open to the public”. Neil Young recorded 11 cover songs in it, and one spoken message to his deceased mother. Because the message and the music sound like they’re coming straight from the 1940s, they are strangely affecting and emotional — which, explains White, was exactly the point. “If, say, his message to his mother had been recorded on Pro Tools, it would have been like, ‘So what?’ There would have been no beauty in it. Recording Neil in the booth gave us a certain vibe. It’s what Neil would have sounded like in the 1940s, recording himself.”

The recordings, lo–fi and scratchy as they are, posed significant challenges for the engineers, as Joshua V Smith explains. “Kevin Carrico, a wizard from Detroit, and I worked on getting Jack’s Voice–O–Graph to function properly between February to August 2013. It’s still a work in progress, but as long as it’s working, we’re scared to touch it! Kevin and I thought of ourselves as ‘electro–mechanically’ engineering the Neil Young album. We had less than a week to modify the booth to Jack’s instructions for Neil’s album project. Some of the modifications included converting it from 45rpm to 33rpm to get more recording time, adding a Nixie tube countdown timer, installing fans in the ceiling, installing a camera and monitor inside of the booth so Neil could watch the disc–cutting process and knew when to start and stop, and installing controls on the back of the booth, so Kevin and I could remotely start and stop it without getting in the way.  Neil Young leaves the Voice–O–Graph after a take.Photo: Jamie Goodsell

Neil Young leaves the Voice–O–Graph after a take.Photo: Jamie Goodsell

“All the records we cut were made of polycarbonate. The original records were made of plastic or a cardboard composite sprayed with acetate or covered in some kind of plastic, and they had grooves cut into them with a steel needle. The grooves in our discs were embossed in them with a tungsten carbide needle. We tried cutting into the polycarbonate but all we got was noise, so embossing was the way to go. We also originally used steel needles and actual acetate master discs cut down to six–inch, but they were $10 per disc! The polycarbonate discs sounded better for our applications and were way cheaper.

“After the discs were cut, we transferred them to one–inch two–track with a 1953 Scully lathe at Third Man that was previously used by Cincinnati’s legendary King Records. We later found that the lathe had induced some noise into the transfer, but by the time we realised this, there was no time to do something about it. Because each disc could only hold 2:27 of audio, I had to do some splices on tape. The tricky part was having to varispeed the two takes before editing them so they were roughly in the same pitch. I did this with discs on which the pitch jumped dramatically in the middle of the take. I ended up having two varispeed boxes, and Richard Ealey at Blackbird Studios made me a switching unit to go between the two boxes. For something that was done with one mic in a phone booth, this project ended up being pretty complicated!”

“After the discs were cut, we transferred them to one–inch two–track with a 1953 Scully lathe at Third Man that was previously used by Cincinnati’s legendary King Records. We later found that the lathe had induced some noise into the transfer, but by the time we realised this, there was no time to do something about it. Because each disc could only hold 2:27 of audio, I had to do some splices on tape. The tricky part was having to varispeed the two takes before editing them so they were roughly in the same pitch. I did this with discs on which the pitch jumped dramatically in the middle of the take. I ended up having two varispeed boxes, and Richard Ealey at Blackbird Studios made me a switching unit to go between the two boxes. For something that was done with one mic in a phone booth, this project ended up being pretty complicated!”