James Taylor (left) and Dave O’Donnell at work in the former’s Barn studio.Photo: Spencer Worthley

James Taylor (left) and Dave O’Donnell at work in the former’s Barn studio.Photo: Spencer Worthley

The art of music production lies in serving the song — and working with James Taylor, Dave O’Donnell felt that modern production trends would hinder his aim of capturing emotive performances.

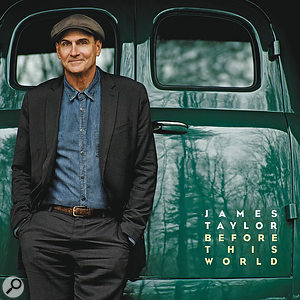

Forty–seven years after the release of his self–titled debut album, James Taylor finally achieved his first American number one in June this year. His 17th studio album, Before This World, surpassed the chart placings of Taylor’s classic early–career albums Sweet Baby James (1970, US number three) and Mud Slide Slim And The Blue Horizon (1971, US number two). Before This World also enjoyed notable chart success in several other countries, reaching number four in the UK, for example.

There has been a 13–year hiatus since Taylor’s previous album of new material, 2002’s October Road, punctuated only by an album of covers called, well, Covers (2008), a few live albums and a Christmas album. In interviews, Taylor indicated that modern life was simply too busy for him to take the time off he needs to write. The other major challenge for any older artist is to come up with something that’s not only relevant today in terms of music and lyrics, but that can also compete in today’s sonic landscape.

Tasked with helping the five–time Grammy–winning Taylor in making sure that Before This World could hold its own in 2015 was the album’s engineer, mixer and producer, Dave O‘Donnell. From his Studio D, an hour’s drive north of New York City, O’Donnell gives a detailed account of the making of the album, which began in January 2010, continued four years later, and involved recording sessions in Taylor’s wooden barn, hotel rooms and various studios across America. At the end of this process, during the final mixdown, O’Donnell found that he was making a slightly different record than he had in mind...

“Initially, when I started mixing, I thought I would make it a kind of hotter and louder contemporary record,” O’Donnell explains. “It really was something that I wanted to do, but it just did not work. I was pushing and compressing things a little more to try to make it a little bit more exciting, or what have you, and what happened was that it sounded exciting for about 10 or 15 seconds, but then I began to get tired of the sound. Quite frankly, it lost some of the emotion of the songs. I don’t mind if people want to make their record hot if it works for the music that they are doing. But with this music it did not work. Having said that, I think many records are too loud these days, and as a result they lose impact. When everything is loud, you lose interest and it can become background noise.”

The Long Road

Given Before This World’s success, O’Donnell clearly made the right call in drawing back from trying to make the album sound overly contemporary. In so doing he drew on decades of experience, going back to the days of analogue and non–over–compressed records. O’Donnell started his studio career in 1984 at the legendary Power Station Studios in New York (now Avatar Studios), where he quickly worked his way up from runner to engineer, and worked with legendary producers like Russ Titelman, Phil Ramone and Neil Dorfsman, as well as the engineers on staff there. O’Donnell went independent in the early ’90s and has amassed an impressive list of credits, including Eric Clapton, Keith Richards, John Mayer, Lyle Lovett, the Bee Gees, Milton Nascimento, Rod Stewart, Cyndi Lauper, Joss Stone, Morrissey, Tina Turner and Ray Charles. In so doing he has been nominated for three Grammy Awards, winning one.

Russ Titelman brought O’Donnell in to engineer and mix October Road, a collaboration which marked the start of a long–standing and very fruitful working relationship: O’Donnell worked with Taylor on the Covers album, the Other Covers EP (featuring material culled from the Covers sessions), and several other projects. Most notably, O’Donnell recorded, mixed and produced the live One Man Band (2007). As Taylor explains in his comprehensive liner notes for Before This World, the first step towards making the album consisted of him inviting O’Donnell, drummer Steve Gadd and bassist Jimmy Johnson to his house in rural Massachusetts. It was January 2010, and the aim was to simply record some demos with no particular purpose in mind. Taylor’s backing band was tracked live at the Barn, with the singer/guitarist in a booth. This photo shows the layout of the large space where the musicians played together.

Taylor’s backing band was tracked live at the Barn, with the singer/guitarist in a booth. This photo shows the layout of the large space where the musicians played together.

“James wanted to have a sense of what he had,” recalled O’Donnell, “which was many musical ideas, including melodies, but only a few lyrics. Steve has worked with James since 2000, and Jimmy since 1991, so they are familiar with James’s music and approach, and part of James’s vision was to have these guys play his stuff. Basically he comes in, plays us what he has and they listen and then start to join in. In 2010 we tried a lot of arrangement ideas, and laid them down, after which James went off and wrote lyrics and more music.”

In The Barn

According to Taylor’s liner notes, he completed the writing for the album at the end of 2013, and in January 2014, invited O’Donnell and the core of his live band — Gadd and Johnson, as well as guitarist Mike Landau and keyboardist Larry Goldings — to a second series of sessions, which produced the basic tracks. These recordings once again took place in the barn adjoining Taylor’s house, with the engineer/producer bringing recording equipment either from his own Studio D or from a hire company.

“The Barn is a property built about 15 years ago on James’s land,” explains O‘Donnell, “about 300 feet away from his home. It’s a very functional, modular kind of space, which he uses for rehearsals and recordings. The main room is just a great acoustic space, not so large as to be too reverberant but also not so small that you get a lot of early reflections. It’s a great–sounding room, and inside it we have a couple of makeshift rooms. We use one as the control room and another as a booth for James to be in, plus there’s a small room with the piano. Nothing is 100 percent isolated, either between rooms or from the outside, but it’s out in the woods so it’s relatively quiet. With no permanent control room or recording gear available at the Barn, Dave O’Donnell set up a temporary working area to house a selection of his own equipment and rental gear. The album was eventually mixed on this Yamaha DM2000 digital desk.

With no permanent control room or recording gear available at the Barn, Dave O’Donnell set up a temporary working area to house a selection of his own equipment and rental gear. The album was eventually mixed on this Yamaha DM2000 digital desk.

“Because James doesn’t have any significant professional recording gear, I move the gear from my studio there, consisting of my Yamaha DM2000 desk, Pro Tools system, a bunch of outboard and microphones, and for the tracking sessions we also hired many additional mic pres and microphones. I prefer to record things pretty flat, so we didn’t need too much outboard during recording, my own main mic pres being the Seventh Circle Audio N72 mic pres, which are a Neve copy, and sound great. It just has knobs for gain and trim, and a phase and a phantom power switch, and on the inside a switch to change the impedance. I used my desk purely for monitoring, and the monitors were my studio’s ProAc Studio 100s.”

No Guidance Needed

Behind the desk at the Barn, with the equipment installed, O’Donnell set about capturing Taylor’s songs, not only technically, but also by giving feedback in his role as the album’s producer. However, with a lifetime of experience of writing songs at the highest level, James Taylor didn’t need a great deal of input in this area.

“As a producer I see my job as making sure the songs are great, by getting great performances, and doing whatever it takes to achieve that,” explains O’Donnell. “It can include choosing the songs, and working on any aspect of them: the tempo, the key, the lyrics, to the structure, parts and so on. With a different artist it can mean a lot of guidance, but with an artist like James you know the songs and the performances will be there; it’s just a matter of capturing these the best you can.”

According to the producer, the way the songs and arrangements found their final form during the 2014 sessions was “very organic. Just like with the demo recordings, James would play us his songs in a guitar/vocal version, and the band would listen and would gradually join in. We occasionally referenced what we had from 2010 — Steve in particular wanted to hear his drum approach for the song ideas at the time — but we did not use any of the demo recordings. Everything was replayed. The guys in his band know what to play, and they then fall into an arrangement and a groove pretty quickly. Things will morph a bit, and they will try different things, and there’ll be discussions about the arrangement, with the band and I offering suggestions.

“James pretty much has the songs finished when he comes in, but he’s very open to anyone’s input. We will try out anyone’s ideas. For a few songs James had more lyrics than were needed, and he was open for input in that as well. But the music guides where the arrangements and production need to be. As soon as he starts singing and playing the guitar, you know it’s James Taylor. That’s the basis and there’s no getting around that.”

Tracking Together

O’Donnell’s own personal preferences, the capabilities of the players he was working with and the facilities at the Barn, all led to Taylor and his band being recorded live, with the singer in his separate booth. “Whoever you’re working with, a good record starts with great basic tracks. To achieve this I prefer recording as many musicians as you can all at once, even as I also enjoy overdubbing vocals and additional parts as a way to enhance or add to the song. In general I’m not a fan of setting out to do basic tracks part by part. It never feels as good as playing as much of the music as you can all at once.

“James has a great band, whose members are all capable of playing in any style, so it was easy to get the basics for the bulk of the songs as a full band. When recording a band live in the studio you always know you can edit different takes together, but with this band we never have to. Every song was recorded as a complete take, other than one song in which we tacked on the final chord. In each case we ended up with that magical take. There still was a lot of work to do after tracking, but we knew we were building on a great foundation.

“We recorded one song a day. We’d have lunch together, start recording around one o’clock, and work until dinner at about six. If more work was needed, we’d stay another couple of hours after dinner, and once we got the take James would overdub a few vocal passes to make sure it was all working. Although he was in a separate booth, everyone had very good lines of sight and could see each other. Everyone also was using headphones, and did their own headphone mix, using Aviom A16 personal mixers. There was leakage, but I like that. It’s helpful in creating an overall sense of ambience and space. And again, with these musicians we did not need to worry about fixing mistakes.”

Miking Details

“My mic setup and signal chains were pretty similar for both the 2010 and 2014 sessions. On Steve’s drums I had a Sennheiser MD421 and an Electro–Voice RE20 on the kick, the snare had a Shure SM57 on top and bottom and also an AKG C451. Steve played brushes for the album, and the 451 is a little brighter, which was right for certain songs. The hi–hat also had a C451, the toms had Sennheiser MD421s, while the overhead mics were Apex — inexpensive Chinese–made tube mics that have been modified by Roy Hendrickson at Avatar. They sound great, a bit like Neumann U67s. I also had a Telefunken C29 Copperhead as a mono overhead, which sounded wonderful, plus several ambient mics, including a pair of Neumann U87s and a pair of U47s, and sometimes a third pair. We did not use all these mics on every song, I just had them there so I could use what was appropriate for each song. The mic pres on the drums were Neve 1081s, with the only outboard being a Pultec EQP1A on the snare, and [Empirical Labs] Distressors on the kick to grab any sudden peaks, because Steve is very dynamic. Steve Gadd is one of the world’s leading session drummers and a long–time member of James Taylor’s backing band.

Steve Gadd is one of the world’s leading session drummers and a long–time member of James Taylor’s backing band.

“The bass went direct via Jimmy’s DI box, and going via a Neve 33609 [compressor], not doing a lot, again just grabbing the peaks. The electric guitar amps had a Shure SM57 going into a Neve 1081 and a Beyer M160 going into a Mercury M76. Mike gets his tone exactly right, and you just have to put some mics in front of his cabinet and, for the rest, stay out of the way. His cabinet was to the left of Steve Gadd, about 15 feet away, and we had some blankets around it, so we could give it its own space, but there definitely was some spill. Mike also played a nylon acoustic guitar, which was recorded via its pickup, going through a Millennia mic pre and then a Neve 33609.

“We had several different keyboards, spread out over the room. I wanted to use real keyboards, so there are only a few synth pads on one or two songs, tucked in low. The main keyboards Larry used were two Wurlitzers, a Fender Rhodes, a B3 organ and a Yamaha C7 grand. I recorded the latter with Schoeps CMC6 mics, with CMC–6 Ug cardioid capsules, going into a pair of Avalon VT–737SP mic pres. We also had a [Neumann] U67 on the low end of the piano, into a Millennia mic pre, which was sometimes mixed in at a low level. The Rhodes and Wurlitzer were recorded direct, though we did also mic the speakers, but I didn’t use those tracks. The Wurlitzer went through a Roland JC120 which was placed in another room, with an SM57 on it. The amp sound added a bit of bite.

“On James’s voice, which we in almost all cases overdubbed once the basic tracks were laid down, we always have a Neumann U67, which he also owns now. I think he has used that exact mic since Hourglass [1997]. We always try different mics, and this time had a new Telefunken C12 and a Telefunken ELAM 251. All three mics were in front of James, as close by and with the capsules aligned to avoid phase issues, but the 67 really is the right mic for him, so we used that predominantly. I did sometimes mix in some of the C12 and the 251, because they have a little bit more definition than the 67. The mic pres were my Seventh Circle Audio N72s. Multiple mics were used on Taylor’s vocal and guitar, though most of his live vocal performances were later replaced.“On James’s guitar we had another 67, and also a Telefunken M260, which I first used at Germano Studios in New York on Keith Richards’ acoustic guitar, when we were recording his new solo album [Crosseyed Heart, released this September, and engineered and mixed by O’Donnell]. We also had a DPA 4099, which clamps on the guitar, so you can get really close to the strings, plus there was a direct, going via James’s Fishman Aura — they modelled some sounds for him, and it sounds great. The mics went through my Seventh Circle Audio mic pres, and also some Distressors.”

Multiple mics were used on Taylor’s vocal and guitar, though most of his live vocal performances were later replaced.“On James’s guitar we had another 67, and also a Telefunken M260, which I first used at Germano Studios in New York on Keith Richards’ acoustic guitar, when we were recording his new solo album [Crosseyed Heart, released this September, and engineered and mixed by O’Donnell]. We also had a DPA 4099, which clamps on the guitar, so you can get really close to the strings, plus there was a direct, going via James’s Fishman Aura — they modelled some sounds for him, and it sounds great. The mics went through my Seventh Circle Audio mic pres, and also some Distressors.”

Travelling Band

Once the backing tracks were complete, a significant amount of work remained to be done. Taylor still had to finish the lyrics for a couple of songs, and overdubs of strings, horns, backing vocals and percussion were planned. The next step was a visit to Avatar Studios in New York, where they recorded strings for the song ‘Snowtime’ and horns for ‘Stretch Of The Highway’ and ‘You And I Again’, arranged by Rob Mounsey, plus Sting’s harmony vocal on the title track.

In March, they travelled to United Recorders, formerly Ocean Way, in Los Angeles to record percussion and backing vocals with Taylor’s regular singers, Arnold McCuller, David Lasley, Kate Markowitz and Andrea Zonn. The latter also added some solo fiddle parts. “We had a U47 on Arnold, C12s on Kate and Andrea, and another Neumann on David, probably a U67, or maybe a Telefunken 251,” recalls O‘Donnell. “I ran them all through the Neve console’s mic pres and nice 1176s, not applying a lot of compression, again they were just set to grab peaks. The fiddle had a direct, but I mainly used a U67, while the percussion would have had different mics, depending on what Luis [Conte] was playing, but it probably was a 421 on the congas, and the studio’s great old C12s on the shakers and tambourines, plus a Copperhead as a nice ambient mic. We also cut the basic tracks there for a new song, ‘Wild Mountain Thyme’, which was bass, piano and James on acoustic guitar.”

Taylor came back home to record vocals to two songs for which he had completed the lyrics, ‘Angels Of Fenway’ and ‘Montana’, and to be present for a session with the legendary Yo–Yo Ma playing a cello part on two songs, again arranged by Rob Mounsey. O’Donnell recorded Ma with a B&K 4011 as the main mic, with some Copperhead, B&K 4006 and M260 mixed in, all going through his Seventh Circle Audio mic pres. The remainder of the overdubs were recorded while Taylor was on tour at MilkBoy Studio in Philadelphia and GCR Studios in Buffalo, NY. O’Donnell: “At MilkBoy Larry Goldings played piano on ‘Snowtime,’ and James added some backing vocals, and at GCR we recorded the drums and backing vocals for another new song, ‘Jolly Springtime’.”

O’Donnell recorded all the material for Before This World to Pro Tools at 24–bit, 96kHz: “I was never a big fan of 44.1, and I feel that 96k is definitely better for acoustic music. With 24/96 I thought for the first time that digital sounded good.”

Be Prepared

After each group of sessions, O’Donnell would bring his gear and the recorded material to his Studio D, where he would tinker with the results, cleaning them up, editing them, and doing what he calls “pre–mixing”. He elaborates: “I use my studio mainly to edit and mix. There are some acoustic screens hanging from the ceiling and scattered around, to absorb certain frequencies and cut down on reflections. In addition to my ProAcs I also have Griffin G2B monitors, which I love. They are very flat, have a ribbon tweeter and sound very musical to me. Dave O’Donnell’s gear usually resides here, at his own Studio D, but is racked ready to be taken elsewhere!

Dave O’Donnell’s gear usually resides here, at his own Studio D, but is racked ready to be taken elsewhere!

“Originally the idea was to do the final mix at Avatar, or somewhere else with a nice Neve console, so I only did very basic things at my studio, occasionally dialling in a plug–in or a hardware insert where things were obviously needed, but I always had in mind that I’d end up taking the sessions to a big room. I’d work on the material while James was on tour, and when he had a break he wanted to work on the album. So I’d bring all my equipment up to the Barn, and we’d work there on comping and pre–mixing, and also did some additional overdubs. Yes, we transported my gear each time. We got that down to a science! Rick Kwan, who helped with engineering, and Sean Fay, the production assistant, would come and meet me each time with a truck, and help move the stuff.

“Because of the way James’s schedule went, we ended up mixing everything at his and my place, on my Yamaha DM2000 desk. It has four banks of 24 channels, and 48 channels at 96k, plus some very good internal EQs and effects, like reverbs. For me it’s great to be able to work with faders, and although we went digital through the DM2000, I think it did sound better than just staying in the box. In general, going out of the box will give you a wider image, with more depth, and the Yamaha will also do that. Particularly for a project like this, going through a mixer sounds much better. I plugged analogue outboard into the Yamaha console inserts, and also connected outboard to the Pro Tools hardware inserts. Some of the hardware included my Vertigo VSC2 compressor, which I love, and the TC Electronic 4000 as my main digital reverb.”

In The Mix

‘Stretch Of The Highway’ is a mid–tempo song with a feel, groove and horn section a little reminiscent of Steely Dan, but still inimitably James Taylor because of the dominating presence of his vocals and acoustic guitar. The song’s 92–track session is very well organised and transparent, with, from top to bottom, one DI bass track, 24 drum audio tracks, five percussion audio tracks, one electric guitar track, two Wurlitzer audio tracks, six B3 organ audio tracks, seven acoustic guitar audio tracks, a lead vocal track, 22 backing vocal tracks, and 10 horn tracks, plus assorted aux, submix and final mix tracks.  This composite screen capture shows the entire Pro Tools Edit window for ‘Stretch Of The Highway’.

This composite screen capture shows the entire Pro Tools Edit window for ‘Stretch Of The Highway’.

O’Donnell: “When I mix, I tend to have everything in [ie. not muted] most of the time. I get a good rough, and at that point I may go through each item as needed. It’s not necessarily in order, I just go for what strikes me. It often is the drums and bass, because they involve working on the low end, but it could also be the guitar, or the vocals, or something else. In the case of James’s records, his vocals and acoustic guitar are very much the focus. I might first spend some time working purely on either his vocals, or the acoustic guitar sound, fine–tuning the different mics on each. The acoustic guitar and the drums are also an essential part of the dynamics of the record, and it was with them in particular that I noticed that if I compressed too much, I was losing the emotion. When James and Steve dig in it is for a reason!

“‘Stretch Of The Highway’ was the first song that we tracked, and it always felt great. It was not a difficult song to mix. The roughs were always good, so the final mix was simply a question of finishing where we left off. Having said that, I did still go through each track, just to double–check things, and I did dial in several pieces of outboard, as well as quite a few plug–ins. I used the Summit TLA–100A compressor on the bass, and on the kick drum the Heritage Audio 2264E Neve duplicate, which sounds excellent. Their 8173 modules are also great.

“The plug–ins on the drums included the Waves CLA76 [compressor] and the GML EQ, to roll off some low end on the snare. Steve’s cymbals all were miked separately — he has amazing–sounding cymbals — and he did an additional cymbal overdub in this song in the choruses, to add to the song’s momentum. The drum room mics came out as a stereo pair on the console, and I used the Waves Q–Clone working with the Heritage EQ, taking out around 300Hz. Because we had set up several sets of room mics, at different distances, I could adjust the size of the ambience as needed. I added very little reverb on this track, it’s almost all the natural room sound. The liner notes make mention of the ‘Aquaduct reverb chamber’, which is a live chamber located outside of the Barn, and which was used on things like percussion.”

Massive Cajongos

“The main percussion track was cajongos [a cross between a cahon and a set of bongos!], with the Waves Vintage Aphex Aural Exciter. I prefer the real Aural Exciter, but using it in the digital domain you get some latency, so it’s slightly out of phase, but in a bad way. There were a couple of songs in which I figured out a way to patch the hardware Exciter in and use it, for example as a direct insert on a guitar track, but if I wanted it on several different instruments, I ended up using the plug–in. I also sent the cajongos through the Tonelux 500–series TX5C compressor. A lot of the 500 series doesn’t sound great to me, but I love those compressors, and in this case I used them to enhance the ambience on the cajongos. The tambourines had just the [Waves] Renaissance Compressor, to grab peaks and even things out.

“I ran the electric guitar track through the Purple Audio MC77 limiter, and printed that back into the session, and that was all it needed. I combined the Wurlitzer DI and amp tracks and put a Seventh Circle Audio B16 compressor on the submix track, via an insert. There’s also a slap echo from the UAD EP34 plug–in. The B3 organ has three tracks, left and right and the lower cabinet, and they are also going to a submix track, with the Massenburg EQ plug–in for a bit more definition, plus it has a de–esser plug–in to take away some abrasiveness the sound had. There’s a second B3 overdub, which also has the Massenburg, but not the de–esser.”

“Beneath the B3 tracks are James’s tracks. The first one is his Godin MIDI guitar, which he overdubbed. We had a microphone on it, and also recorded it direct, and had to slide one track 619 samples to time–align them. The main acoustic guitar was recorded with the Fishman Aura box, a U67, DPA 4099 and the 260. I used the Massenburg EQ plug–in to roll off some low end at 80Hz, and on two of the guitar tracks I had the Waves Renaissance compressor and the Aphex Aural Exciter. Unusually, the Aura was used considerably in this song, because James had been singing the whole time during tracking. He later overdubbed most of his vocal part, but the acoustic guitar part had such a great feel that rather than redo it, we’d bring up the acoustic guitar mics when he isn’t singing, and used the Aura track when he is singing, to make sure you don’t hear any original vocal bleed.

“Beneath the B3 tracks are James’s tracks. The first one is his Godin MIDI guitar, which he overdubbed. We had a microphone on it, and also recorded it direct, and had to slide one track 619 samples to time–align them. The main acoustic guitar was recorded with the Fishman Aura box, a U67, DPA 4099 and the 260. I used the Massenburg EQ plug–in to roll off some low end at 80Hz, and on two of the guitar tracks I had the Waves Renaissance compressor and the Aphex Aural Exciter. Unusually, the Aura was used considerably in this song, because James had been singing the whole time during tracking. He later overdubbed most of his vocal part, but the acoustic guitar part had such a great feel that rather than redo it, we’d bring up the acoustic guitar mics when he isn’t singing, and used the Aura track when he is singing, to make sure you don’t hear any original vocal bleed.

“James’s lead vocal has a Massenburg EQ plug–in, and then goes to an outboard Massenburg compressor, and into the Q–Clone for some EQ. I also used the TC Electronic 4000 reverb on his vocal. The backing vocals for this track were recorded both at United Recording in LA and the hotel room in San Francisco. They had come up with a different chorus part while on tour which they liked better, so we re–recorded some of the parts in San Francisco. They had the Massenburg plug–in EQ, a Waves Puigchild 660 [compressor], and some Aphex Aural Exciter, plus the UAD EMT 250 and Roland Dimension D [chorus] plug–ins. Underneath the backing vocals are the horns, which had the Q–Clone with the Heritage EQ and some EQ and compression from the DM2000.

“Finally, the mixdown went through the AMS Neve 8816 and Vertigo compressor, both all analogue. I did not do anything additional to the final mix, which was sent to Ted Jensen at Sterling Sound in New York for mastering.”

Going Soft

“In general I’m still more a fan of hardware than of plug–ins,” says Dave O’Donnell, “although during the last couple of years plug–ins have become significantly better, and there are some newer companies making things that are more interesting than just analogue gear emulations. This week I’ve been trying out some FabFilter and DMG plug–ins, which to me is the way to go, to some degree using traditional analogue principles but not necessarily trying to emulate specific gear. Though the danger with some of these plug–ins is that you end up mixing with your eyes, rather than your ears! When I mix I have my screen off to the side, so I can listen without seeing things, because no matter how experienced you are, looking at what happens on the screen changes the way you hear it.

“I think digital hardware reverbs still sound better, but, despite what I said above, the best plug–in reverbs I have heard are analogue emulations, ie. the UA EMT 140 and the EMT 250. I also use the Massenburg MDW plug–in for corrective EQ, and when I need to add some brightness or punch I’ll use analogue outboard, often with the Waves Q–Clone and one of my analogue EQs. It’s a similar situation for me with compression. I like some digital compressor plug–ins because they allow you to really fine–tune the timing and amount of compression, and they also are good at basic smoothing out and grabbing peaks. But when I am looking for something more aggressive, or a certain sound, I usually prefer analogue gear. In general analogue outboard still has more impact, more presence — I don’t mean brightness — and more depth. But in the end there are no rules, I’ll use whatever works. It all depends on the source material.”

Hotel World

James Taylor set off on a summer tour in June 2014, which had been scheduled to promote the forthcoming album — but with writing and tracking unfinished, some of the final overdubs were actually recorded during the tour. This involved two noteworthy hotel room sessions, in San Francisco and a few days later again in Los Angeles. “Those were fascinating sessions,” remarked O’Donnell. “We set up the singers in one room, and James and I were in another, which was a makeshift control room with a Pro Tools rig, some outboard and a pair of speakers. It worked very well, much better than I thought it would. Everybody was relaxed and comfortable. One thing that really helped were the ASC Studio Traps acoustic screens between the singers, which were provided by Stephen Jarvis, who brought most of the gear we used in San Francisco. The traps were excellent. They provided great isolation between the singers, even though there was still some leakage of course. In terms of mics, I used the Apex modified mics, which I had earlier used on the overheads, and two modified 414s provided by Stephen Jarvis, and I brought my Seventh Circle mic pres.”