With a bit of hard work to counter unwanted masking effects and muddiness, everything becomes clear...

Axel Ermes does front‑of‑house sound for bands such as Die Krupps and Project Pitchfork. Although he's already an accomplished mixing engineer in the live arena, he contacted SOS recently because he felt that his own studio productions weren't competing well enough with commercial material. His main concern was that the individual parts weren't always easy to pick out, and there was a general muddiness to the sound. This is a very frequent problem with Mix Rescue projects, but it can be tricky to solve, because there's usually no single, broad‑brush change that will fix it — most often it's a combination of numerous nips and tucks that's required. So in this month's column, I'd like to illustrate a number of different strategies that can really help improve mix clarity.

Defining Kick Drum & Bass

One of the biggest problem areas with the original mix was the bass end, and I started my remix there. Investigating the raw kick drum first (in my Cockos Reaper‑based mix system), it was immediately apparent that its burst of low‑end power (centred around about 55Hz) felt as though it was arriving significantly later than the sample's pronouced attack transient, but was then trailing on quite a long time after each hit. This meant that the beat always seemed a bit sluggish and lacking in 'oomph', no matter how high you set the fader in the mix, and there was also precious little room left for the main bass synth to manoeuvre. High‑pass filtering at 57Hz helped a little, by reducing the apparent length of each hit (in the way that low cuts often do), and I also cut 8dB of high end to pull back the transient, which was making my ears bleed! Although the Cockos ReaEQ shelf in question was ostensibly set to 890Hz, the slope was so gentle that the curve only properly reached ‑8dB by around 7kHz, and was still 3dB down at 400Hz.

The low‑frequency time‑lag was immune to these measures, though (I don't actually know any off‑the‑shelf plug‑in that will target this kind of thing), so I opted instead to use an added kick‑drum sample to fill in the missing bass attack onset. The sample in question was a one‑shot from Equipped Music's excellent Breakbeat Jazz sample library, and although it was longer than I needed in its raw form, it was easy to shorten it with an early fade‑out so that it just plugged the other drum's low‑frequency 'pre‑delay', making the composite sound appear much more coherent and in time.

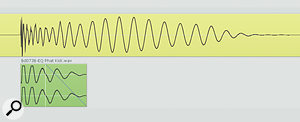

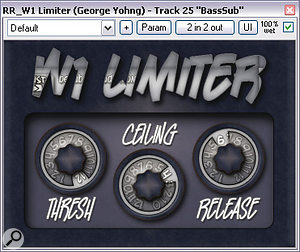

The yellow audio region here is the main kick‑drum sample, and you can see how the onset of the longer‑wavelength low‑frequency information is delayed compared to the start of the drum hit. This made the drum sound out of time. Mike's solution was to add an additional kick‑drum sample (green audio region) to beef up the low‑frequency attack. Notice how this has been shortened with a fade‑out to avoid conflicting with the existing low-end energy.The biggest problem with the main bass-synth line was that the low end was very inconsistent, and the wide pitch range of the part made it difficult to attack this with any kind of frequency‑selective processing. Another issue was that the part had been recorded with delay effects, and low‑end echoes were cluttering up the mix. Again, I opted to sidestep both of these thorny processing problems by simply reprogramming Axel's bass part by ear, and then using that MIDI data to trigger a sub‑bass synth part alongside, using my usual low‑pass-filtered triangle‑wave patch from Reaper's Reasynth. However, I didn't completely replace the original part, because there was lots of timbral information in the mid-range that was important to the song's character: instead, I high‑pass filtered it at 90Hz, to let the sub‑bass synth take over at the low end. Setting all the new part's note velocity values to maximum made it fairly consistent in level, but I also used an instance of George Yohng's W1 Limiter to utterly nail it to the wall, so that I could rely on it holding a dependable position in the balance.

The yellow audio region here is the main kick‑drum sample, and you can see how the onset of the longer‑wavelength low‑frequency information is delayed compared to the start of the drum hit. This made the drum sound out of time. Mike's solution was to add an additional kick‑drum sample (green audio region) to beef up the low‑frequency attack. Notice how this has been shortened with a fade‑out to avoid conflicting with the existing low-end energy.The biggest problem with the main bass-synth line was that the low end was very inconsistent, and the wide pitch range of the part made it difficult to attack this with any kind of frequency‑selective processing. Another issue was that the part had been recorded with delay effects, and low‑end echoes were cluttering up the mix. Again, I opted to sidestep both of these thorny processing problems by simply reprogramming Axel's bass part by ear, and then using that MIDI data to trigger a sub‑bass synth part alongside, using my usual low‑pass-filtered triangle‑wave patch from Reaper's Reasynth. However, I didn't completely replace the original part, because there was lots of timbral information in the mid-range that was important to the song's character: instead, I high‑pass filtered it at 90Hz, to let the sub‑bass synth take over at the low end. Setting all the new part's note velocity values to maximum made it fairly consistent in level, but I also used an instance of George Yohng's W1 Limiter to utterly nail it to the wall, so that I could rely on it holding a dependable position in the balance.

Once I'd relieved Axel's original bass part of its low‑end duties, I concentrated my efforts on accentuating its character in the mix. After some experimentation, I ended up using Bootsy's NastyLF bass enhancer for this, applying a hefty low‑end boost with 12dB of saturation to thicken up the low‑mid tone, and then boosting 8dB at 2.4kHz with a broad ReaEQ peaking filter, to add some bite. (However, a further high, sequenced synth layer that appears during the choruses made the overall bass tone at those points feel a bit too abrasive, so I had to cut that part a few decibels above 3.5kHz to compensate.) A final touch was to shift the bass parts 8ms earlier, as this seemed to lock the sequenced bass rhythm more closely with the new solidified kick sound.

Loop Dissection

A sub‑bass synth part was added to make the low end of the bass line more dependable. To keep this part absolutely consistent in terms of level, the trigger note velocities were all set to maximum, and then the synth's output was limited using George Yohng's W1 limiter.

A sub‑bass synth part was added to make the low end of the bass line more dependable. To keep this part absolutely consistent in terms of level, the trigger note velocities were all set to maximum, and then the synth's output was limited using George Yohng's W1 limiter.

Once the main powerhouse of the rhythm was operating, I began adding in the various programmed rhythm parts. A simple snare backbeat during the choruses took very little work: a gentle low‑end roll‑off below 1kHz and a little audio editing to shorten its sustain tail. The latter not only saved me some mix real-estate, but also better emphasised the overall rhythm. More complex to deal with were three sampled loops, and in all these cases I decided to take my normal approach and chop them up into slices for 'multing' across numerous tracks. This isn't as tedious a task as it might initially seem, because even quite a long loop doesn't usually take more than 10 minutes to chop up into its individual hits in any modern DAW system, and in metronomic music like this you can easily copy and paste edited sections to rebuild the whole part from that single iteration. What's more, the benefits of that bit of multing donkey‑work can be enormous, and are available even if you're working on a comparatively entry‑level mixing system.

For a start, once you've got all the hits laid out, it's easy to adjust a given loop's programming if it conflicts with other elements of the rhythm track, and this is something I find myself doing all the time. Maybe one of the open hi‑hats is making a bar feel bogged down, so I might replace it with a closed hi‑hat from elsewhere in the loop. Maybe the groove of one loop is conflicting with that of other parts of the programming, and therefore reducing the groove's 'bounce', or filling up too much space in the mix; in which case you may get a tighter fit just by shifting around the relative timing of each component instrument, or adjusting individual slice durations. Both these strategies were used in this mix, but that was just the start.

Exerting enough control over the individual component instruments within a drum loop can be difficult at mixdown, unless you spend a bit of time slicing up the loop and multing the slices to different tracks, as Mike did with all three loops in this month's remix.Another important thing the multing allowed me to do was individually balance and process different instruments within the loop. So, for example, I wanted very little low end from any loop's internal kick hits (I already had plenty of energy in the lower octaves!), but other elements were able to retain more of their natural frequency range. In the case of the persistent offbeat hi‑hats, I was able to smooth off an over‑spiky transient with some soft clipping (from GVST's GClip), and widen it with Kjaerhus Audio's Classic Chorus plug‑in, all without affecting the loop's kick and snare parts. I also pitched that hat sample down a tone, to give it a smoother timbre that seemed to work better with the track. One of the advantages of working on sliced audio is that you can pitch‑shift individual regions without worrying about the tempo changing if the processing adjusts the audio's playback speed, and that flexibility can often open the door to better‑sounding shifting.

Exerting enough control over the individual component instruments within a drum loop can be difficult at mixdown, unless you spend a bit of time slicing up the loop and multing the slices to different tracks, as Mike did with all three loops in this month's remix.Another important thing the multing allowed me to do was individually balance and process different instruments within the loop. So, for example, I wanted very little low end from any loop's internal kick hits (I already had plenty of energy in the lower octaves!), but other elements were able to retain more of their natural frequency range. In the case of the persistent offbeat hi‑hats, I was able to smooth off an over‑spiky transient with some soft clipping (from GVST's GClip), and widen it with Kjaerhus Audio's Classic Chorus plug‑in, all without affecting the loop's kick and snare parts. I also pitched that hat sample down a tone, to give it a smoother timbre that seemed to work better with the track. One of the advantages of working on sliced audio is that you can pitch‑shift individual regions without worrying about the tempo changing if the processing adjusts the audio's playback speed, and that flexibility can often open the door to better‑sounding shifting.

The main thing to be careful of when working with slices is where instruments within the loop overlap or play together. So, for example, if open hi‑hats sometimes coincide with kick‑drum hits, you can't just remove the high end from the kick without unduly affecting the hi‑hat. My usual work‑around is to replace the composite kick/hat hit using a combination of kick‑only and hat‑only hits copied from elsewhere in the loop. That little dodge gets me out of almost any scrape.

Per‑slice processing made fairly light work of two of the three loops, but the second, which was being used to define the chorus sections, felt a bit underwhelming: there were a few excessively spikey transients (which we didn't need, given the power of the main kick) but otherwise everything sounded really soft and mushy. You'd fade it up to try and hear it, and just end up poking your eye out with the peaks while generally muffling everything else in the mix. I handled the transients fairly swiftly using Reaper's Jesusonic Transient Controller and then mashed the whole loop through MDA's Bandisto, to give it some more character. Distorting a mixed loop can be a bit hit and miss, and in this case it emphasised the loop's high‑hat more than I wanted, but I wasn't able to equalise against that problem without losing nice sustain elements on other instruments. I could have split the distortion out to the individual slice tracks, but first I tried Reaper's multi‑band compressor, ReaXcomp, to see if that could give a quicker fix — which it did (give or take a bit of additional EQ sculpture). I used fast, hard‑knee high‑frequency limiting, and then carefully set the high band's threshold to trigger primarily on those errant hi‑hats.

The last element of the rhythm programming was a single little cymbal track, which had a lot of unnecessary attack and a rather underwhelming tail, so I hammered it with 25dB of 8:1 compression from Reaper's ReaComp to turn the tables, ducking the attack transient and pulling up all the sustain. However, an attack time fast enough to to catch the initial transient also caused the compressor to introduce some distortion, so I slackened that off a bit and compensated for it using the plug‑in's Pre‑comp control. This parameter adds 'lookahead' to the compressor, so that it effectively begins responding early, and dialling in 4ms Pre‑comp did the business nicely, in the light of my chosen 2.5ms attack time. I also added ping‑pong delay to this cymbal, to try to give it yet more sustain, but this was actually the only delay/reverb send effect I added to any of the rhythm parts — another factor thst worked in my favour in terms of maintaining mix clarity.

Blend Improvements

Once the main hi‑hat offbeat hit had been chopped out of its loop, it could be processed in a variety of ways to make its tone more appealing: offline pitch‑shifting of the audio region itself to mellow the timbre; soft clipping to round off the transients; and chorusing to add some stereo spread.

Once the main hi‑hat offbeat hit had been chopped out of its loop, it could be processed in a variety of ways to make its tone more appealing: offline pitch‑shifting of the audio region itself to mellow the timbre; soft clipping to round off the transients; and chorusing to add some stereo spread.

One of the biggest problems Axel had created for himself while recording was that he'd not ensured that his guitar and synth parts were suitably in tune. The trouble with tuning is that it's not just a musical issue, it's also a mix issue, because it affects the way the whole production blends. I chose to use static offline pitch‑shifts for the necessary remedial work, because they tend to produce the fewest unwanted artifacts with polyphonic audio. In the case of the guitars, different chords blended best with different shifts, so I went through each part in turn, shifting individual snippets by ear. The synths tended to be more stable, but I did take the opportunity to shift the end of one of the long synth-pad notes to a more concordant pitch on a couple of occasions, because otherwise its long decay tail seemed to undermine one of the changes of harmony.

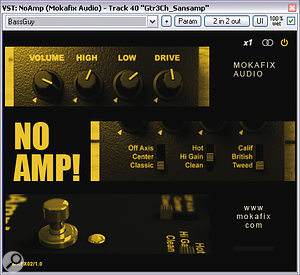

Guitar distortion and synth filter sweeps tend not to respond very well to pitch‑shifting of any kind, but I felt that the slight 'softening' side effects of the necessary small pitch‑shifts were a reasonable price to pay for the improved transparency of a better‑tuned mix. The guitars were already quite mushy‑sounding, because (in common with many small‑studio productions) the amp had been driven a bit too hard during tracking, and the pitch‑shifting only softened the tone further, so I compensated for this in two ways. Firstly I added in a parallel distortion from Mokafix's NoAmp, removing everything below 600Hz from the effect return. Normally I find myself using some kind of phase adjustment to achieve the best balance between the distortion and the unprocessed tracks, but in this case the timbre seemed fine without.

The second tactic I used to give the guitars a bit more bite and urgency was to layer in a simple eighth‑note 'chug' part from Nine Volt Audio's Big Bad Guitars, a heavy‑rock REX loop library. This library is great for mix layering lof this kind, because it gives you simple rhythm parts for every scale degree, so it hardly took two seconds to build up a line that matched the song's harmonies. Because Axel had recorded his guitars with their delay effects, an added advantage of doing this was that it effectively dried out the guitar sound a little, bringing the instruments apparently further upfront. In order to give a little more rhythmic impetus to the part, I decided to shorten the eighth‑note part to leave gaps between the notes, and then layer in a more sustained quarter‑note part alongside. Although it still wasn't particularly thrilling (or natural‑sounding) to listen to in its own right, it was very effective for adding body and movement to Axel's main sound.

The improved tuning already helped the blend a great deal, but there were extra points to be scored through further judicious low‑end pruning across all the sustained harmonic and melodic parts. The Big Bad Guitars needed quite a lot of low‑end roll‑off, for example, to stop them muddying the mix, while the choir and piano sounds had to be rolled off below about 1kHz to avoid them sounding subjectively dull in the context of the full arrangement. A filtered string‑machine pad (which you can hear working fairly subtly during the choruses) was filtered at around 700Hz and then compressed to bring out the resonant sweeps, and serves as a textbook illustration of where plug‑in order is important. I applied the EQ before the compressor, because I wanted to even out the mid-range and high frequencies that were left after the filtering. If I'd EQ'd after the compression, the dynamics processing would have been confused by the considerable lower‑frequency information in the raw audio file, and therefore wouldn't have operated as effectively.

I've demonstrated in a number of previous Mix Rescues (most recently in SOS May 2010 and SOS December 2009) how timing corrections can help with blend, so while I was in a corrective mind-set, I applied my audio editing tools to some timing discrepancies too. This was mostly a question of shuffling sections of the guitar parts around slightly, especially for the guitar solo.

Unmasking Tricks

Here you can see some of the ways the guitar sounds were improved for the remix: the original parts (orange regions) were extensively edited for pitching and timing in the arrange page; some additional guitar layers were added from Nine Volt Audio's Big Bad Guitars library (green regions) to thicken and dry out the sound; and parallel distortion was added from Mokafix's freeware NoAmp plug‑in.

Here you can see some of the ways the guitar sounds were improved for the remix: the original parts (orange regions) were extensively edited for pitching and timing in the arrange page; some additional guitar layers were added from Nine Volt Audio's Big Bad Guitars library (green regions) to thicken and dry out the sound; and parallel distortion was added from Mokafix's freeware NoAmp plug‑in.

Another important strategy for increasing clarity in the mix involves reducing the effects of masking. Masking is a psychological effect whereby every instrument has the potential to obscure important aspects of other instruments, making them less audible at a given fader level. The more tracks you have in your mix, the more they mask each other, and the harder it is to hear everything clearly. There are lots of anti‑masking techniques, but for lead instruments it's useful to think in terms of giving each one some kind of unique sonic fingerprint, because that tends to make it stand out better in the mix.

There will, of course, be as many ways of doing this as there are engineers, but in this mix I made particular use of the concept with the vocal parts. All the vocals had heavy compression on them to bring up as much of the performance character as I could, and for this I applied Digital Fishphones' freeware Blockfish compression, with its assertive VCA emulation and fast time‑settings. I also engaged the Complex mode, which puts two stages of gain reduction in series, a configuration that tends to achieve heavy compression a bit more musically.

The original piano part presented so many mix problems that it turned out to be easier just to reprogram the part using 4Front's Truepianos, using the setting shown.For the verses, I added in a ring‑modulator send effect — not exactly everyone's first choice for lead vocals, admittedly, but I've recently discovered that it can add a really good 'growl' to the vocal delivery for some styles, without obviously turning your singer into a Dalek! I used MDA's absurdly simple RingMod plug‑in and adjusted the frequency setting to taste. Bear in mind that ring modulation of any pitched part can introduce dissonant overtones, and subtle tweaks to the modulation frequency can do a lot to adapt these to your mix. (That said, it was partly the dissonances that helped pull the vocal out of the track in this mix.) Because Reaper lets you easily route audio around in its effects window, I also took the opportunity to have separate ring‑modulation settings for the left and right audio streams, so that it gave some stereo width. Further width was achieved by plumbing the ring‑modulated return through the Leslie rotary‑speaker emulation within GSI's Organized Trio virtual instrument. Accommodating this effect in the mix then required some vigorous high‑pass and low‑pass filtering, both before and after the ring modulation, to funnel the effect's added harmonics exactly where I wanted them. Ring‑modulation also lent a hand during the chorus sections, where Martin Blankenburg's MB MooRiMo plug‑in did the honours. This has a stereo modulation mode built in (the 'Wid' switch setting), and again I massaged the modulation frequency until I found harmonics that seemed to work with the vocal tone.

The original piano part presented so many mix problems that it turned out to be easier just to reprogram the part using 4Front's Truepianos, using the setting shown.For the verses, I added in a ring‑modulator send effect — not exactly everyone's first choice for lead vocals, admittedly, but I've recently discovered that it can add a really good 'growl' to the vocal delivery for some styles, without obviously turning your singer into a Dalek! I used MDA's absurdly simple RingMod plug‑in and adjusted the frequency setting to taste. Bear in mind that ring modulation of any pitched part can introduce dissonant overtones, and subtle tweaks to the modulation frequency can do a lot to adapt these to your mix. (That said, it was partly the dissonances that helped pull the vocal out of the track in this mix.) Because Reaper lets you easily route audio around in its effects window, I also took the opportunity to have separate ring‑modulation settings for the left and right audio streams, so that it gave some stereo width. Further width was achieved by plumbing the ring‑modulated return through the Leslie rotary‑speaker emulation within GSI's Organized Trio virtual instrument. Accommodating this effect in the mix then required some vigorous high‑pass and low‑pass filtering, both before and after the ring modulation, to funnel the effect's added harmonics exactly where I wanted them. Ring‑modulation also lent a hand during the chorus sections, where Martin Blankenburg's MB MooRiMo plug‑in did the honours. This has a stereo modulation mode built in (the 'Wid' switch setting), and again I massaged the modulation frequency until I found harmonics that seemed to work with the vocal tone.

Another track to which I applied special processing for unmasking purposes was the piano line, which was fighting for survival in the mix, even after I'd replaced the raw track with a more suitable MIDI part (see 'If All Else Fails: Replace!' box). Two send effects gave the track its own character: the first was an unnatural‑sounding long reverb from GSI's freeware TimeVerb plug‑in, which added some high mid‑range 'zing' and coloured the instrument's sustain. The second was a 3/16‑note ping‑pong delay that lengthened the sustain and added stereo width.

A final 'old as the hills' unmasking trick I applied was ducking some backing parts in response to the main drums. This not only reduces the amount by which the drum sounds are masked, making them appear clearer and louder in the balance, but can also mimic the effects of the ear's internal safety 'compression' scheme, thereby creating an increased psychological illusion of power. There are lots of ways you can achieve this kind of ducking, but I chose to use compressors inserted on the relevant backing parts, keyed via their side‑chains from the drum tracks.

Artificial Additives

Some of the freeware effects Mike used to combat masking of the lead vocal and piano lines: the rotary‑speaker effect within GSI's Organized Trio virtual instrument; Martin Blankenburg's MooRiMo ring‑modulator; and GSI's Timeverb.

Some of the freeware effects Mike used to combat masking of the lead vocal and piano lines: the rotary‑speaker effect within GSI's Organized Trio virtual instrument; Martin Blankenburg's MooRiMo ring‑modulator; and GSI's Timeverb.

As the mix began to come together, I found myself yearning for a touch more internal detail in the track, as well as enhanced 'ebb and flow' between sections. To address this, I flipped a few mute buttons here and there to adjust the arrangement, and also added a variety of textural synth parts (from Heavyocity's Evolve) and sound‑effects samples (from Zero G's Elektrolytic), in very much the same way I described back in SOS July 2010's Mix Rescue. Once a first draft had wended its way to Axel, he also came back with the suggestion that we shorten the outro section to tighten things up further, which was a good idea. However, 'artificial additives' and song restructuring only really make a useful difference once mix‑clarity problems have already been dealt with, so there's no point in wasting time with those if your sonics are still knee‑deep in the mud.

If you're one of the many home recordists who find themselves cursed with muddy‑sounding mixes, hopefully this month's column has provided some real‑world examples of a few of the most common remedies: careful selection/combination of kick and bass sounds; deconstruction of sample loops into multed slices; tuning/timing correction; and application of unmasking treatments to lead lines and other hook parts. Even one of those factors can make a noticeable difference; improve all of them and you can truly transform a mix.

When All Else Fails: Replace!

When you're mixing MIDI‑triggered parts, there are some times when it's better just to reprogram the part from scratch than to try to bludgeon a dodgy performance into submission using fusion‑powered plug‑in processing. It was the piano part in this mix that fell into this category. Although the part was essentially quite straightforward, the MIDI data's velocity shaping was a bit suspect — the wrong notes in the phrase always appeared to be stressed, and the occasional two‑note chords kept no consistent balance. While compression could tidy up the level unevenness, the tonal unevenness couldn't be sorted out in this way — a hard piano note isn't just louder, it's also brighter. EQ could also perhaps have rebalanced one of the two‑note chords, but any setting that sorted that out wouldn't have worked for the other chords, because the balance between the notes was always changing. Serious multing might have produced an acceptable result, as might powerful frequency‑selective processes such as dynamic EQ, but that all felt rather too much like using a sledgehammer to crack a nut. Instead, I recreated the part using 4Front's great little Truepianos virtual instrument, whereupon it was a walk in the park to rebalance the track from the MIDI data — and it also allowed me to choose a brighter piano tone that cut through the mix better.

Rescued This Month

This month's track is by the band Girls Under Glass, who cite an eclectic mix of electro, post‑punk and gothic influences including Sisters Of Mercy, Red Lorry Yellow Lorry, Bauhaus, Danse Society, Front 242 and Portion Control. Following the departure of the band's keyboardist and producer last year, SOS reader Axel Ermes stepped into this role, and Lars Baumgardt and vocalist Volker Zacharias provide guitars. This particular song, 'We Feel Alright' (which started out as a homage to Apoptygma Berzerk's 1993 song 'Bitch'), was recorded using Apple Logic 8 and mixed through a Mackie 8-Bus mixing desk.

Remix Reactions

Axel Ermes: "I've heard your mix now several times and I'm still impressed, as are the other two guys. It's absolutely the way I like it: everything much clearer and cleaned up. The vocals are more 'in your face' than before (without being too loud) and you can actually hear the difference between the kick drum and bass now! The side‑chain pumping of the guitars is pretty effective as well. Usually I'm a bit too lazy to connect all the signals in the right way to achieve this, but I've learned my lesson there. As for all the little bleeps and blurps — great! I'm really looking forward to including those in our live eight‑track version of the song. Thanks for your work!”

Full Project Online!

We've placed audio files and the full Reaper project on the SOS web site at /sos/nov10/articles/mixrescuemedia.htm to help you learn more about Mike's approach to this mix.