This month, we show how manipulating the phase relationships of some tracks in your mix, plus a little disciplined pruning, can revitalise a flat‑sounding track.

The Black Bloc in a drum- and bass-tracking session: recorded acoustic drums can sound great, but remember to think about phase when recording.

The Black Bloc in a drum- and bass-tracking session: recorded acoustic drums can sound great, but remember to think about phase when recording.

Many home recordists seem to find the subject of phase a bit mysterious. I wrote a long article on the subject in SOS April 2008 (/sos/apr08/articles/phasedemystified.htm) to try to clear up any confusion, but there's nothing like a real‑world example to hammer a point home, and this month's remix, for rock band the Black Bloc, fits the bill nicely. Given the influences the band cite (see 'Rescued This Month' box), it should come as no surprise that a tight, live-performance aesthetic is important to their sound, and phase and polarity problems turned out to be one of the big obstacles to achieving this, with not only the drum parts needing careful attention, but also the guitars and lead vocals.

Multitrack Drums & Phase

The upper screen here shows a zoomed‑in view of the left and right overheads files, as submitted for the remix. The drum hit you can see is a snare drum, and you can see that the polarity of one of the mics is clearly inverted: the waveform is an approximate mirror image. Also notice that the snare appears slightly later on one channel than the other, which skewed the stereo and affected the sound in mono. The lower screen shows how Mike matched the polarity and timing for a punchier and more mono‑compatible sound.

The upper screen here shows a zoomed‑in view of the left and right overheads files, as submitted for the remix. The drum hit you can see is a snare drum, and you can see that the polarity of one of the mics is clearly inverted: the waveform is an approximate mirror image. Also notice that the snare appears slightly later on one channel than the other, which skewed the stereo and affected the sound in mono. The lower screen shows how Mike matched the polarity and timing for a punchier and more mono‑compatible sound.

My primary concern with the band's original mix was the soft and unfocused sound of the drums, because the driving, funk‑tinged performances of the drummer and bass player were crying out for something tighter and punchier. Kick and snare samples had been triggered to try to ameliorate the situation, but they hadn't helped a great deal, so I muted everything and began to troubleshoot the sound from scratch.

As usual, the first tracks I faded up were the overheads. They typically capture a mix of the whole kit and therefore tend to be the most important tracks in terms of defining the kit's overall character. Panning the two mics hard left and right to start with revealed one howler straight away: the polarity of one of the mics was inverted compared with the other. Zooming in on the audio, you could clearly see the snare waveforms in mirror image, and the sound had that weird holographic quality to it, which makes you feel a bit like your brain's being sucked out through your ear!

A simple polarity inversion switch on the offending channel was enough to switch off the cranial hoover — or so I thought. Suddenly, about three minutes through the track, the sound suddenly went freaky again! Somehow, it appeared that one of those overhead mics was only out of phase for the first half of the track. This wasn't something I'd ever encountered before, and I was worried it might also afflict some of the other tracks too, so I immediately scoured them for tell‑tale signs. And a good thing, too, because the main snare track had a similar anomaly, although the switchover actually occurred a couple of seconds earlier. Engineer resting their Daiquiri on the console during the take? Never a good idea...

Anyway, once I'd identified the problem, it wasn't tricky to polarity‑invert just those audio regions affected. However, I'd also noticed, while examining the overhead waveforms, that the snare wavefronts weren't very well time‑aligned — in other words, that the snare wasn't the same distance from the two microphones. (In fact, given that sound travels roughly a foot per millisecond, it looked like one mic was four or five inches further away.) Shifting the audio on one of the tracks so that the wavefronts lined up had two effects: firstly, the snare's stereo position felt a bit more focused into the centre of the stereo image, where I wanted it; and secondly, the drum's tone was slightly clearer and snappier when summed to mono.

Anyway, once I'd identified the problem, it wasn't tricky to polarity‑invert just those audio regions affected. However, I'd also noticed, while examining the overhead waveforms, that the snare wavefronts weren't very well time‑aligned — in other words, that the snare wasn't the same distance from the two microphones. (In fact, given that sound travels roughly a foot per millisecond, it looked like one mic was four or five inches further away.) Shifting the audio on one of the tracks so that the wavefronts lined up had two effects: firstly, the snare's stereo position felt a bit more focused into the centre of the stereo image, where I wanted it; and secondly, the drum's tone was slightly clearer and snappier when summed to mono.

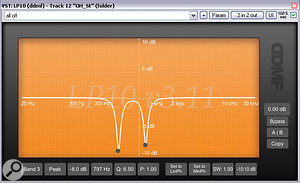

Once all that was sorted out, I returned to the matter of evaluating the overheads sound. Because there were no tom‑toms in the kit, and close mics were provided for snare, kick, and hi‑hat, I wasn't hugely bothered about instrument balance issues; one of the big advantages of recording close mics is that they allow you much more scope to rebalance the kit components at mixdown. More of a concern was the tonality of the snare, which had a couple of very pronounced undamped resonances. I traced these ringing frequencies to 354Hz and 797Hz using Schwa's Schope frequency analyser (which I find much quicker and more accurate than trying to track them down manually with an EQ band) and then zapped both with 12dB of cut from high‑Q peaking filters. How much to cut in these instances is best judged in the context of a full mix, though, so I later revisited these settings with the other instruments going and discovered that slightly less severe attenuation produced a meatier sound.

Drum Overheads & Close Mics

There were over‑prominent snare resonances in the overheads signal at 354Hz and 797Hz, as you can see in the upper screen here. Targeting those with narrow peaking‑filter cuts courtesy of DDMF's LP10 plug‑in (lower screen) made for a much more appropriately balanced snare sound.

There were over‑prominent snare resonances in the overheads signal at 354Hz and 797Hz, as you can see in the upper screen here. Targeting those with narrow peaking‑filter cuts courtesy of DDMF's LP10 plug‑in (lower screen) made for a much more appropriately balanced snare sound.

I then had a listen to the two kick‑drum mics: one placed inside the shell and the other (judging by the time delays involved) positioned just in front of the kit. The outer mic had a little spill from the rest of the kit, but otherwise sounded great, so I all but left that alone. My only real processing touch was to enhance the tightness of the drum with SPL's Transient Designer plug‑in (running on a Universal Audio UAD2 processing card), emphasising the punch with about 5dB attack and shortening the sound's release with ‑6dB sustain.

Mixing the outer close mic with overheads, it was clear that the low‑frequency elements of the overheads were making the kick drum a bit too distant and ambient, which I didn't feel would sit well with the precisely punctuated bass playing, so I applied a 24dB/octave high‑pass filter at 120Hz, using DDMF's LP10 linear-phase EQ, to clean things up. I then checked to see which close‑mic polarity setting might give a better combination, but there wasn't much difference between the two settings now that there was so little real low end in the overhead response.

The other kick track was quite unnatural‑sounding, even for an internal close mic: though well endowed with beater slap and flabby, rumbling low end, it lacked anything much else. For this reason I high‑pass filtered it at 30Hz with another instance of LP10, setting limits on the reach of its low end, and then kept its contribution quite low in the mix. The pair of mics seemed to work better than the outside mic on its own, but there was a tubby‑sounding build‑up of energy around 200Hz, so I pulled this down with 4dB of peaking cut. I also experimented with lining up the initial kick waveform peaks of the two close‑mic tracks by sliding one slightly backwards in time and, while this technique won't produce something worthwhile every time, here it seemed to give a slightly harder and more cohesive outcome that I liked.

The other kick track was quite unnatural‑sounding, even for an internal close mic: though well endowed with beater slap and flabby, rumbling low end, it lacked anything much else. For this reason I high‑pass filtered it at 30Hz with another instance of LP10, setting limits on the reach of its low end, and then kept its contribution quite low in the mix. The pair of mics seemed to work better than the outside mic on its own, but there was a tubby‑sounding build‑up of energy around 200Hz, so I pulled this down with 4dB of peaking cut. I also experimented with lining up the initial kick waveform peaks of the two close‑mic tracks by sliding one slightly backwards in time and, while this technique won't produce something worthwhile every time, here it seemed to give a slightly harder and more cohesive outcome that I liked.

As usual, the snare‑drum close mic over the top of the drum wasn't particularly pleasant to listen to, despite a reasonable dose of attack transient, because it lacked noise components and possessed an extended resonant and metallic‑sounding sustain tail. Taking out the worst of the resonances with hefty LP10 peaking filter dips at 865Hz and 1037Hz helped a little, but even so it was clear that this mic was only going to be useful for adding attack, rather than full‑bodied noisy sustain, to the overheads. With that in mind, I mixed the mic in with the overheads, checking its polarity switch for the beefiest attack, but found that I couldn't get the snare hitting as hard as the kick without +3dB of attack from another Transient Designer plug‑in.

Under‑snare Magic

A software version of SPL's Transient Designer (in this case running on Universal Audio's UAD2 platform) was useful for adding snap to both kick and snare. This screen shows the setting used for the former.

A software version of SPL's Transient Designer (in this case running on Universal Audio's UAD2 platform) was useful for adding snap to both kick and snare. This screen shows the setting used for the former.

The under‑snare mic was, as you'd expect, out of polarity with the top snare mic, but it was also very slightly out of sync as well, so polarity inversion, combined with a little timing nudge, ended up giving the crispest bite. The mic now supported the rest of the drum mix pretty well, adding welcome rasp and noise to the existing 'poing'! I did need a couple more narrow peaking cuts, though, this time at 156Hz and 179Hz, to rein in some ringing of the kick drum (or possibly an otherwise idle tom‑tom) that had been picked up.

I love under‑snare mics, because they usually catch all the instruments in the kit to some extent, and so can be used to help glue a kit together in much the same way overhead mics can. One way to maximise this cohesion is to compress the under-snare to bring up the spill contributions, much as you might with overheads or room mics. However, the beauty of the under‑snare placement in this situation is that compressing it doesn't carry as great a risk of washing out the sound with room ambience, and this was especially relevant here, as the drums had been recorded in quite a large room with quite a wet sound. I tried a couple of less‑than‑gentle compressors to give the under‑snare mic a hammering, eventually deciding on SSL's freeware Listen Mic Compressor, which added a nice edge to the snare sound in particular.

The hi‑hat was the last track to blend in, and because the hat's tone was pretty good, with well‑controlled snare spill, all it warranted was a polarity check (no inversion required) before I could fade it up and pan it to match the hat position in the overheads. There was no point in getting too anal about the panning, though, because hat spill on all the other close mics militated against pinpoint imaging. I could have achieved a sharper stereo picture by targeting this spill with careful filtering and gating, but this would have been at the expense of the 'organicness' of the kit as a whole, which appeared to me to be much more important.

The upshot of all this was that some very basic EQ, a couple of instances of Transient Designer and a single compressor were enough to dramatically improve this drum mix — but only once the important phase/polarity groundwork had been done. Yes, I also did some further polishing of the drums with parallel compression, tempo‑sync'ed stereo delay, and hall reverb, but none of that would have amounted to a hill of beans without the basic sound already being 90 percent of the way there. So the moral of the story is this: when mixing drums, you ignore phase relationships at your peril!

Guitar & Vocal Phase Rotation

The overhead and snare tracks all switched their polarity halfway through the track. Here's the waveform of the snare recording: can you tell where the polarity switches? Answers on a postcard...

The overhead and snare tracks all switched their polarity halfway through the track. Here's the waveform of the snare recording: can you tell where the polarity switches? Answers on a postcard...

You've got so many options when mixing a multi‑miked drum set that the simple phase tools I've already mentioned (polarity inversion and time‑shifting) rarely feel underpowered for the task. Bass usually also seems to respond well to these same tools, in my experience. However, when you start combining different electric-guitar mic signals, perhaps even from different amps driven by a splitter box, greater control is often called for — and this is where specialised phase rotators come into their own.

These devices are designed to adjust the phase relationships between the different frequencies in a sound, but without any adjustment of the frequency response. This effect should be pretty much inaudible on soloed sounds, but the moment you use it on one signal of a multi‑mic setup, it alters the phase‑cancellation effects within the combined sound, and can therefore radically alter the final tone, particularly if the contributing mic signals are at similar levels.

The guitars and lead vocals were both improved using phase rotation from Little Lab's new IBP Workstation plug‑in, running on the UAD2 platform. Here's the setting used for the guitars.I've often used Betabugs' handy little Phase Bug utility in this capacity in previous columns, but I was keen, on this occasion, to try out the more controllable software emulation of Little Labs well‑known IBP phase rotator (running on Universal Audio's UAD2 DSP system), so I turned to this instead when trying to make sense of the three separate signals that contributed to each of the main guitar parts. In its virtual incarnation, IBP offers variable adjustment of both time delay and phase and, as with any phase rotator, setting it up is very much a process of trial and error: you just have to spend a bit of time twiddling the controls until you like what you hear. In this case, I considered the guitars to be a bit too soft and distant‑sounding (partly on account of a heavy delay effect that had been printed during recording), and wanted to focus the sound and give it more presence.

The guitars and lead vocals were both improved using phase rotation from Little Lab's new IBP Workstation plug‑in, running on the UAD2 platform. Here's the setting used for the guitars.I've often used Betabugs' handy little Phase Bug utility in this capacity in previous columns, but I was keen, on this occasion, to try out the more controllable software emulation of Little Labs well‑known IBP phase rotator (running on Universal Audio's UAD2 DSP system), so I turned to this instead when trying to make sense of the three separate signals that contributed to each of the main guitar parts. In its virtual incarnation, IBP offers variable adjustment of both time delay and phase and, as with any phase rotator, setting it up is very much a process of trial and error: you just have to spend a bit of time twiddling the controls until you like what you hear. In this case, I considered the guitars to be a bit too soft and distant‑sounding (partly on account of a heavy delay effect that had been printed during recording), and wanted to focus the sound and give it more presence.

It's important to remember that you'll only hear the effects of the phase rotation when the different mic signals are all mixed together, so there's no point in soloing the track while processing! Another thing to bear in mind is that most EQ will also adjust the phase relationships of frequencies within the processed signal — so you'll probably need to revisit your phase rotator setting after you've EQ'd, to check that you're still getting the best out of it. I tried phase‑adjusting all three guitar parts, but only one of them really benefited, and as I decided to put this part lower in the mix anyway, it meant that the phase‑related improvement to the guitar sound was quite small — although still definitely worthwhile. By contrast, my final application of phase‑rotation, for the lead vocals, made an enormous difference.

Mike used distortion from a Fender Champion 600 emulation running in IK Multimedia's Amplitube X‑Gear to add aggression to the lead vocal. The sound of this was then refined by switching the default AKG C414 mic emulation for a Beyerdynamic M160 model, and moving the virtual mic off‑axis to the cone.The band had suggested that some kind of distorted vocal sound, like Roots Manuva's on Leftfield's 'Dusted', might be suitable for their production, and I was in support of this idea because it enabled me to make the vocals appear aggressive at a lower level, giving the band as a whole enough room to sound powerful in context. For this purpose, I set up a send from the heavily compressed main vocal channel to IK Multimedia's Amplitube X‑Gear, and surfed through the amp models looking for a suitable contender. Many of the models simply sounded too big and fuzzy, whereas in this application smaller amps tend to produce more controlled and usable results. Finally, I happened on a Fender Champion 600 model that sounded promising, and then adjusted the volume control and flicked through the different virtual mic models and placements to refine things a little more. This was pretty close to what I was after, but lacked grit, so I chucked the output through another instance of the SSL Listen Mic Compressor for that.

Mike used distortion from a Fender Champion 600 emulation running in IK Multimedia's Amplitube X‑Gear to add aggression to the lead vocal. The sound of this was then refined by switching the default AKG C414 mic emulation for a Beyerdynamic M160 model, and moving the virtual mic off‑axis to the cone.The band had suggested that some kind of distorted vocal sound, like Roots Manuva's on Leftfield's 'Dusted', might be suitable for their production, and I was in support of this idea because it enabled me to make the vocals appear aggressive at a lower level, giving the band as a whole enough room to sound powerful in context. For this purpose, I set up a send from the heavily compressed main vocal channel to IK Multimedia's Amplitube X‑Gear, and surfed through the amp models looking for a suitable contender. Many of the models simply sounded too big and fuzzy, whereas in this application smaller amps tend to produce more controlled and usable results. Finally, I happened on a Fender Champion 600 model that sounded promising, and then adjusted the volume control and flicked through the different virtual mic models and placements to refine things a little more. This was pretty close to what I was after, but lacked grit, so I chucked the output through another instance of the SSL Listen Mic Compressor for that.

To this point I'd been auditioning the distortion channel solo, in order to hear more easily the effects of the distortion controls and home in on a sound rich in frequencies that were recessed in the lead vocal itself. However, you can't evaluate any mix processing properly out of context, so once I'd set up an initial X‑Gear patch, I hopped out of solo mode... and had a nasty surprise. The distortion effect was comb‑filtering appallingly with the main lead vocal track, knocking such a huge hole in the low mid‑range that the singer might as well have been rocking the inside of a Coke can! IBP rode to my aid again, fortunately, and I was relieved when a quick twist of the Phase Adjust knob snatched victory from the jaws of defeat — still not a simple addition of the two tracks, but a much more satisfying combination that made the vocal more aggressive‑sounding and also blended it better with the track as a whole.

Why Linear‑phase EQ?

I've already mentioned that most EQ affects not just the frequency response of a processed signal, but also the phase‑relationships between its different frequency ranges. However, increasing numbers of plug‑ins are available that offer the option of 'linear phase' equalisation, where no phase‑relationship changes occur: IK Multimedia T‑Racks 3's Linear Phase EQ, 112dB's Redline Equalizer and DDMF's LP10 are three that spring to mind.

Linear‑phase EQ has a reputation for greater transparency in critical processing situations (and higher CPU munch into the bargain!), so it's often more closely associated with mastering than mixing. However, where you're working with multi‑miked recordings, linear‑phase EQ lets you make frequency‑balance changes to individual mic channels without affecting their phase relationship with others. The magnitude of this benefit is fairly small if you're working with decent recordings where the required EQ changes are minimal, but when you need to really push your EQ settings for heavier sound‑sculpting, linear‑phase EQ can justify its extra CPU cost by retaining a more coherent sound with less phasiness. It was for this reason that I chose to use linear‑phase EQ for dealing with the guitar parts, as I ended up using fairly steep high‑pass and low‑pass filters in 112dB's Redline EQ to bracket the most promising part of each mic signal.

I also experimented with linear‑phase EQ for the notches I punched into the various drum tracks, but ended up deciding against using it there because of one of its most common side‑effects: pre‑ringing. Most people quickly discover that high‑Q filters in normal EQ 'ring' at their turnover frequency, but where normal EQ rings after the signal event that excites it, linear‑phase EQ can ring before it, which sounds pretty weird. When I tried using linear‑phase peaking filters to notch out the problematic undamped drum frequencies on the snare and overhead mics, the pre‑ringing side‑effects became too obtrusive. I compared both Redline EQ and LP10, but they both exhibited similar foibles, and switching out of linear‑phase mode gave a much better result, albeit at the expense of more interaction with other drum parts.

Just A Phase?

If your primary tactic for tackling mixdown phase issues in the past has been to run away shrieking, I really hope that this month's Mix Rescue feature has demonstrated just how much you could be losing out. Despite the mystique surrounding the subject of phase, it's honestly not terrifically difficult to deal with, as long as you give it the attention it needs — and if you're able to get this aspect of your productions right, it should help you to achieve a sonic clarity and punch that other processing options will struggle to match.

Arrangement Tweaks

In addition to the processing changes I made, a fair amount of my work on the remix involved working on structure and arrangement issues. Although I had no problems with the slow‑paced inevitability of the band's build‑ups, there were a number of points where the rhythm section appeared to be just marking time, so I decided to slim down some of these eight‑bar sections to four bars to keep the momentum going. The hiatus before the third and final section also broke up the flow of the track unnecessarily, so I contracted that as well.

Some copying and pasting of the single double‑tracked guitar part added a bit of textural variety to help with the overall feeling of build‑up, particularly in the final section. While I often find myself weeding out unnecessary parts in Mix Rescue, there was very little of that required here, given the clearly focused band line‑up, but one thing did find its way onto the cutting‑room floor: the electronic drum pattern (from a Korg Kaoss Pad) that provided a consistent mechanical backdrop to the original mix. This part obscured a lot of the drummer's interesting low‑level details, and was also making his groove seem bogged down, so I ended up eliminating it everywhere except during the middle section.

The added delay special effects were another significant addition, and while it's difficult to rationalise the instinct that led me to try those, I think it was mainly because the heavy delay effects on the guitars (which I couldn't change at all, as they had been printed while recording) initially seemed somehow unrelated to the rest of the track, whereas the presence of similar vocal effects made the guitars feel more integral to the production as a whole. I also wanted to give the choruses a more contrasting textural signature, and the long feedback delays (in tandem with a change in the bass sound) provided this.

Rescued This Month...

This month's track comes courtesy of Yorkshire‑based band the Black Bloc, whose brand of politically charged rock has been described as Rage Against The Machine on acid! The line‑up consists of Michael Bush (lead vocals), James Bush (guitar), Paul Stewart (bass, backing vocals), and Ady Hoyle (drums). They've already had enthusiastic support from BBC Introducing and The Joe Strummer Foundation and have been touring like madmen too, clocking up 100 gigs in their first four months alone and appearing at major festivals such as Glastonbury, Shambala, and Wychwood. In 2007, the band recorded their debut album with producer Steve Whitfield, and are currently working on a follow‑up, which should appear later this year.

Remix Reactions

The Black Bloc: "Usually we're working with an engineer/producer at mixdown and chipping in throughout, so it was a strange experience hearing the remix for the first time after such a comprehensive rework. No drum machine! Considering that the whole song had been built around it, that was immediately a pretty radical change. The next thing that struck us was how big and ferocious the vocals and drums sounded. Without doubt, Mike definitely got what we were after with the vocals: they're sharp, gritty and pronounced, providing clarity at all volumes, which is something the original mix lacked. When the whole band came in halfway through the first verse, it was apparent that this new mix sounded much clearer. Each instrument had its own defined space and the whole thing sounded wider.

"The next surprise was the delay that had been added to the vocals. Again, when you're used to a song in a certain way, something like this can be quite a shock, and at first it seemed slightly overdone, as if it should have faded out sooner. As the song progressed, though, everything began to fall into place: Mike had tapped into the trippy nature of the guitar effects, and the vocal effects were complementing and enhancing them perfectly. As the song moved through the outro, all these effects began to merge together to create a really eerie soundscape, and it was at this point that we began to realise why the drum machine had been removed: it allows the song to breathe, providing space for the vocal and guitar echoes to play out and entwine, and for Ady's ghost notes and Stewie's bass to cut through the track.

"Overall, the song now manages to sound both raw and polished at the same time. Not only this, but Mike's managed to knock almost a full minute off the track time, and though it's hard for us to admit (considering the time we spent writing it), he's improved the structure along the way. Besides the improved mix, what we've realised from this Mix Rescue is the value of having independent creative input from somebody outside the band, especially when it's someone with the knowledge and experience Mike clearly has behind him. If you've agonised over the writing of a song for a long time it's very difficult to detach yourself from that, so it's constructive to have a fresh discerning pair of ears to provide the finishing touches. Certainly, if someone had suggested ditching the drum machine we'd have written the idea off straight away, but in fact the gains that came from having that extra space far outweighed the loss of that particular part's industrial/electronic/machinegun‑like character.”

Audio Files

We've placed a number of audio files — including both the original track and Mike's remix — online so that you can hear for yourself the changes that were made: /sos/apr10/articles/mixrescueaudio.htm