Putting in the effort at the front end of the production process can save countless hours when it comes to mixdown — as this month's remix demonstrates.

The key to putting together productions in a hurry and on a shoestring is the art of decision-making, and 'leaving options open' at the tracking stage all too often means not putting in enough effort to get a usable sound for each signal printed! Every time you defer a recording choice, it multiplies the complexity of the mixing process and frequently makes obtaining a good end-result trickier — not to mention a lot more time-consuming. This month's Mix Rescue is a case in point, because many instruments were multitracked (presumably for mixdown flexibility), when a well-judged single-channel signal would have made mixing much less challenging. Mix Rescuee Cristina Vane.

Mix Rescuee Cristina Vane.

Half A Guitar Sound

My biggest bone of contention was the main acoustic guitar, a centrepiece of the song's rhythm and harmony, given singer-songwriter Cristina Vane's folk influences and stylistic connections with artists such as the Cranberries, Dido, and Alanis Morissette. The decision to multi-mic important acoustic-guitar parts is understandable in principle, since it makes it possible to capture a more holistic 'picture' of the instrument's frequency dispersion, and individual tracks can also be panned at mixdown to widen the image, which a lot of listeners find appealing.

That's the theory, at least. In practice, this particular project's multi-mic approach didn't seem very carefully thought out. A microphone up by the instrument's neck had caught plenty of potentially useful string jangle, but at a cost of rather too much mechanical rattle and buzz, as well as some unflattering booms and thuds from the instrument's low mid-range resonances. The latter afflicted the second mic even more, as it had been placed quite close to the guitar's sound hole, drawing a veil over the tone and providing little real harmonic density in the mid-range. Plus, when the tracks were mixed together, the spaced-mic configuration contributed an unflatteringly nasal comb-filtering effect, as well as questionable mono-compatibility if the signals were panned. The guitar's direct output had been recorded too, but DIs always sound pretty lifeless, and this one certainly wasn't any sonic 'get out of jail free' card. Even if I'd majored on the DI, that wouldn't have remedied the periodically wayward tuning in the lower registers.

To me, these tracks imply a series of unmade tracking decisions. Are the strings in tune? Can I make the instrument sound better in the room? Do my mics catch a usable balance of string jangle, body resonance, pick noise, fret buzz, and so forth? Does the balance and phase of my second mic usefully complement the first? What's the DI signal going to be used for? As a result of these unmade decisions, the three recorded tracks still only managed to catch half a guitar sound.

Salvage & Replacement

To add complexity to the upper spectrum of the supplied acoustic rhythm-guitar part, Mike created this super-short 'micro-reverb' treatment with Christian Knufinke's SIR2 convolution engine. The impulse response in question is taken from a small portable radio.

To add complexity to the upper spectrum of the supplied acoustic rhythm-guitar part, Mike created this super-short 'micro-reverb' treatment with Christian Knufinke's SIR2 convolution engine. The impulse response in question is taken from a small portable radio.

In the first instance, I resolved to do what I could with the two mic signals. Fairly savage cuts cleared out some of the low mid-range mud, as well as de-emphasising that suspicious tuning. Fast, peak-sensitive compression from Melda MCompressor and a touch of tape simulation from Toneboosters TB_Ferox helped take the edge off the string rattle and picking transients, as well as helping with the general sustain, while Reaper's ReaJS plug-in's Phase_adjust module improved the phase interaction between the two mics to a degree. For an additional dose of sustain, I turned to a 'micro-reverb' patch (a 20ms burst of coloured-sounding early reflections with a narrowed stereo spread and 20ms of pre-delay) from Christian Knufinke's SIR convolution engine, which also filled out the mid-range a good deal, as well as solidifying the centre of the stereo image when the mics were panned.

However, despite these measures (and a half-dozen smaller EQ and dynamics tweaks besides), it quickly became clear that some fresh recordings would be required to turn this mix around. I'm no acoustic guitarist myself, so I contacted Joe Lonsdale at Joe Public Studios for help, and he quickly pinged me back with a good selection of extra parts. By way of contrast, he'd managed to capture a round, even tone using a single Oktava MK012 omni mic in combination with one of those little stand-mounted microphone baffles. The parts were child's play from a mixing perspective, so the few bits of processing I did use were mostly concerned with fitting Joe's sounds around what was already in the mix: a couple of EQ cuts cleared space for the vocals and bass in the low mid-range; some fast HF compression ducked out some transients, as these were already prominent enough in the original recording; and some dynamics processing imposed Cristina's rhythmic envelope onto Joe's more sustained playing during the choruses, so that his added layer became less audible in its own right. The last of these I implemented using Reaper's unusual Parameter Modulation facility, but if I'd been using another DAW platform I could have achieved a similar end by inserting an expander on Joe's channel and feeding its side-chain input from Cristina's.

Three Tracks Of Kick...

This spectrum analysis display from Schwa's Schope plug-in compares the spectrum of the AKG kick-drum mic (in green) with that of the Yamaha NS10 'mic' signal. As you can see, the AKG mic's signal already had plenty of sub-bass, which rendered the NS10 channel largely redundant.

This spectrum analysis display from Schwa's Schope plug-in compares the spectrum of the AKG kick-drum mic (in green) with that of the Yamaha NS10 'mic' signal. As you can see, the AKG mic's signal already had plenty of sub-bass, which rendered the NS10 channel largely redundant.

The multi-channel theme pervaded the drums production too, with both kick and snare receiving three tracks. The main kick-drum mic was an AKG model, presumably their ubiquitous D112, given the characteristic emphasis in the sub-200Hz and 2-5kHz regions. This mic can be just the ticket for heavy rock bands, where the low end needs to thump you in the chest and you want the beater to slice through a swarm of anti-social guitars. In this song, however, it felt rather out of place, the mass of LF energy making the mix bottom-heavy and the groove sluggish, while the upper mid-range peak brought the drum too up-front relative to the overall balance. The drum's true mid-range tone, on the other hand, seemed recessed, such that it came across as rather gutless, despite the thundering subs and HF attack.

Some microphone repositioning might have helped here, of course, although it's possible that the engineer had already tried to make the best of the situation in this regard, given that I was able to achieve a more suitable tone with a few careful EQ cuts. However, it mystifies me why anyone then chose to put up an NS10 woofer (wired for use as a microphone) to complement the D112, when all it added to the mix was a superfluous layer of sub-bass, even once its polarity was suitably matched.

The third kick track featured an added sample, carefully triggered from the live performance, but this seriously softened the combined kick-drum timbre with its default polarity, and even when inverted, it still featured an incongruously strong 99Hz pitched resonance, almost like the ring of a tom-tom, which cluttered the mix's low end. As with the NS10 woofer, I was left scratching my head about its intended role, so both of these tracks bit the dust in my mix, while the D112 made it all the way to the final product with little more than EQ.

...And Three Tracks Of Snare!

The snare's trio of tracks comprised top and bottom mics, and an additional sample. The cymbals overwhelmed the snare in the kit's overhead mics (especially once I'd shaved off a good deal of woolliness with high-pass and low-shelving filters), which put pressure on the close mics to provide the bulk of the drum's sound. Unfortunately, it sounded as though the 'SM57 an inch away' approach had been taken over the snare, which tends to militate against sonic realism. Indeed, once I'd notched out an exaggerated 245Hz resonance, what remained was mostly stick attack!

Fortunately, the under-snare mic was actually quite effective in returning some of the noisiness and body to the timbre, although not until its polarity had been inverted, so this may not have been fully appreciated during tracking — hence, perhaps, the decision to add a trigger. Either way, though, the choice of sample struck me as ineffective, simply because it mostly provided the same kind of 'attack' and 'punch' components as the mic signals, rather than complementing them by enhancing something less well represented, such as sustain, width or ambience. If there'd been masses of spill on the snare close mics, there might nonetheless have been a solid justification for it, but the close-miking had actually caught the snare sound pretty cleanly in this situation.

Fabfilter's Pro-C compressor was set up with fast attack and release times to rebalance the snare drum's attack spike against its more characterful release envelope.

Fabfilter's Pro-C compressor was set up with fast attack and release times to rebalance the snare drum's attack spike against its more characterful release envelope.

Once again, three 'options' fell short of delivering a satisfying sound, where fewer tracks could almost certainly have achieved better results. For example, the overheads might have been positioned from the offing to deliver a better snare sound, reducing the pressure on the close mics. In that context, a bit of attack definition from a close SM57 might have been enough to complete the picture on its own, without any need for under-snare or sample channels. Even if the overheads had deliberately been left quite cymbal-heavy for later balancing purposes, a few inches more distance on the top snare mic could have made all the difference in the world to the naturalness of the sound without introducing unmanageable levels of hi-hat spill, potentially rendering the sample-triggering redundant.

In the face of the facts, however, my plan of attack began with the sample track's Mute button and the aforementioned polarity and EQ notch tweaks. I then used a series of processors to try to reduce the top mic's attack spike: another instance of TB_Ferox and some fast, hard-knee compression from Fabfilter's Pro-C.This inevitably brought up the hi-hat spill, so I compensated by gating out 6dB of this with Fabfilter's Pro-G. Once the under-snare mic was in the balance, I snuck in a snare sample from Slate Digital's Trigger as a final touch, deliberately removing all its attack so that it only supplemented the sustain of the drum's envelope tail.  This screen shows the additional snare sample Mike triggered alongside the live mic signals. Notice the 20ms attack-time setting, which removes the samples onset transient so that it functions only to enhance the width and noisy sustain of the composite drum timbre.

This screen shows the additional snare sample Mike triggered alongside the live mic signals. Notice the 20ms attack-time setting, which removes the samples onset transient so that it functions only to enhance the width and noisy sustain of the composite drum timbre.

Building The Backing

The remainder of the drum set came together fairly easily: Crysonic's Transilate helped to smooth out some cymbal stick noise in the overheads, and an instance of the Sonalksis CQ1 dynamic EQ expanded the floor tom's low spectrum to rein in some uncontrolled LF ringing in sympathy with the kick hits, but otherwise the processing was just a few bands of EQ, as one would normally hope. The bass processing was also pretty straightforward. This dynamic EQ setting from Sonalksis CQ1 was used on the floor-tom close mic to reduce sympathetic ringing at low frequencies in response to kick-drum hits. The main EQ fended off some unhelpful woofer flapping with a 12dB/octave high-pass filter at 28Hz, and a 7dB high shelving cut at 3.3kHz prevented the instrument's upper-spectrum mechanical noises distracting from the vocal.

This dynamic EQ setting from Sonalksis CQ1 was used on the floor-tom close mic to reduce sympathetic ringing at low frequencies in response to kick-drum hits. The main EQ fended off some unhelpful woofer flapping with a 12dB/octave high-pass filter at 28Hz, and a 7dB high shelving cut at 3.3kHz prevented the instrument's upper-spectrum mechanical noises distracting from the vocal.

To control the bass DI's inherently fairly wide dynamic range, I first inserted Softube's Summit TLA100A emulation, laying on about 7dB of gain reduction and choosing a medium-attack, fast-release setting to increase the sustain without killing too much of the instrument's rhythmic pulse.  Although Softube's emulation of Summit's TLA100A compressor did a fine job of controlling the bass levels in general, it responded a little bit unpredictably until some low-end inconsistency on the recording had been ironed out with Reaper's ReaXcomp multi-band processor.

Although Softube's emulation of Summit's TLA100A compressor did a fine job of controlling the bass levels in general, it responded a little bit unpredictably until some low-end inconsistency on the recording had been ironed out with Reaper's ReaXcomp multi-band processor. However, I was unable to get this compressor responding as smoothly as it usually does, because of some LF inconsistency in the instrument's DI signal, so I preceded the Softube plug-in with a stage of sub-85Hz squeeze from Reaper's built-in ReaXcomp to tackle that.

However, I was unable to get this compressor responding as smoothly as it usually does, because of some LF inconsistency in the instrument's DI signal, so I preceded the Softube plug-in with a stage of sub-85Hz squeeze from Reaper's built-in ReaXcomp to tackle that.

Despite my quibbles with some of the other multi-miking on this project, the two wah-wah electric-guitar parts had been nicely captured with both a Shure SM57 and a ribbon mic, providing two contrasting but complementary sounds that worked very well together in the mix. As a result, I only needed to thin these parts a little with my high-pass filters to fit them into the mix, although I also applied some compression to each part to keep them firmly balanced, from Melda's MModernCompressor and Stillwell Audio's The Rocket respectively.

Two keyboard parts had been supplied: an auto-panned electric piano and a Hammond-style organ. I didn't want to major too heavily on those, for fear of losing too much of Cristina's folk tinge, so I did EQ quite heavily, dipping the low mid-range on both parts to avoid muddiness, as well as reducing their mix 'cut-through' by carving 5dB out of the Hammond's 1.4kHz zone and by low-pass filtering the electric piano at 5kHz.

Vocals Processing

The vocals were nicely recorded, so my mix processing was, again, fairly minimal. There was a little too much proximity effect on the mic, but a super-gentle 25Hz high-pass filter from Fabfilter's Pro-Q and 6dB of broad-bandwidth low cut with Softube's Active Equalizer soon sorted that out, so that the vocal's low mid-range slotted nicely into the mix. Further small EQ tweaks were mainly a matter of adjusting the tone to taste: returning to the Softube plug-in, I applied a broad peak at 1.6kHz to bring Cristina forward a little, but also dipped 2dB with a narrower bandwidth at 4kHz to tackle a touch of harshness, a task I continued in the more surgical Fabfilter plug-in using three small, high-Q, peaking-filter cuts at 1.6kHz, 4.3kHz and 9.9kHz.

Dynamics were pre-processed with a fairly slow-acting setting of Melda's MAutoVolume, before the signal was passed to Stillwell Audio's more assertive The Rocket, working at a 4:1 ratio with a 150ms release time for more 'syllable-level' control. As usual, the faster compression brought up sibilance levels, despite a bit of 7.3kHz EQ boost I inserted in The Rocket's side-chain, so I ended the plug-in series with Fabfilter's Pro-DS de-esser working in its split-band mode. Mike deliberately pushed the Fabfilter Pro-DS de-esser plug-in to process more than just the sibilance on this lead vocal, in order to smooth out a touch of harshness that crept into the vocal tone from time to time. Because I was still a little concerned about upper-spectrum harshness from time to time, I deliberately increased the sensitivity of the algorithm a little beyond the point of just de-essing, so that it also turned down the HF of any over-bright notes. Fortunately, Pro-DS has a Range control which allows you to do this without incurring lisping side-effects by over-processing stronger sibilants.

Mike deliberately pushed the Fabfilter Pro-DS de-esser plug-in to process more than just the sibilance on this lead vocal, in order to smooth out a touch of harshness that crept into the vocal tone from time to time. Because I was still a little concerned about upper-spectrum harshness from time to time, I deliberately increased the sensitivity of the algorithm a little beyond the point of just de-essing, so that it also turned down the HF of any over-bright notes. Fortunately, Pro-DS has a Range control which allows you to do this without incurring lisping side-effects by over-processing stronger sibilants.

The only other vocals were a lead double-track and two chorus harmony lines, and although they had presumably been recorded in a similar manner, I didn't feel the need to process them in as much depth, given their background role, so they all shared the same ReaEQ and ReaComp settings: a 400Hz high-pass filter removed them from the low mid-range picture; 3dB of shelving cut above 5.5kHz helped push them behind the lead; and 6-8dB of 8:1 compression gave the levels a firm hand.

Effects & Final Balancing

Although there were eight different send effects on this particular mix, all were sparingly applied to avoid over-varnishing the basic parts. The heaviest of them was a small room from Lexicon's LXP Native bundle, gelling the close mics and adding a clearer acoustic signature. Starting from a likely-sounding 'Hard Tight Wall' preset, I shortened the reverb time to keep the ambience tight, but opened up the Rolloff control to 14.5kHz and increased the RT Cutoff parameter to flatter the kit's high frequencies. This patch was also used to glue most of the acoustic guitar tracks into the rhythm section.  The main reverb on this remix session was a small-room emulation from Lexicon's LXP Native bundle, with the reverb decay made shorter and brighter using the plug-in's Reverb Time, Rolloff and RT Hicut parameters.The rest of the effects were far more targeted, such as four treatments that were applied only to the vocals. A simple, short 'Dessert Plate' preset from LXP Native gave all the vocal parts some bloom and warmth, but I increased its pre-delay to 18ms to help maintain a fairly up-front impression. Then, just for the lead vocal, I used a bright, wide, 50ms-long plate impulse response (running in Christian Knufinke's SIR2) to enhance the singer's high frequencies and stereo width, as well as a touch of my usual Harmonizer-style, pitch-shifted-delay widening effect. For the choruses, I supplemented this lead-vocal line-up with an additional tempo-sync'ed delay from Softube's Tube Delay, setting its Tone controls for a mellow, middly echo that would lengthen Cristina's sustain in an unobtrusive manner.

The main reverb on this remix session was a small-room emulation from Lexicon's LXP Native bundle, with the reverb decay made shorter and brighter using the plug-in's Reverb Time, Rolloff and RT Hicut parameters.The rest of the effects were far more targeted, such as four treatments that were applied only to the vocals. A simple, short 'Dessert Plate' preset from LXP Native gave all the vocal parts some bloom and warmth, but I increased its pre-delay to 18ms to help maintain a fairly up-front impression. Then, just for the lead vocal, I used a bright, wide, 50ms-long plate impulse response (running in Christian Knufinke's SIR2) to enhance the singer's high frequencies and stereo width, as well as a touch of my usual Harmonizer-style, pitch-shifted-delay widening effect. For the choruses, I supplemented this lead-vocal line-up with an additional tempo-sync'ed delay from Softube's Tube Delay, setting its Tone controls for a mellow, middly echo that would lengthen Cristina's sustain in an unobtrusive manner.

I'd chosen to keep the lead vocal subjectively quite dry-sounding in this mix, so I took the precaution of feeding its effects a heavily de-essed signal to stop them picking up too much on consonants. I created a separate, de-essed channel for this purpose, unassigned from the mix bus, feeding all the effects from there so I wouldn't have to change my main dry-signal processing at all. This method also meant that I didn't need to keep adjusting the de-esser threshold if I automated my reverb sends later in the mix, as I'd have had to if I'd been de-essing at the start of the effect-return channel's plug-in chain. My last effects sends were a single-tap, quarter-note echo thickening up the chorus guitars; a complex stereo ping-pong from Fabfilter's Timeless, embellishing one of Joe's chiming final-chorus overdubs; and a long, rich Lexicon LXP Plate wash accenting a few of the acoustic-guitar spread chords, wah-wah guitar lines, and electric-piano lines.

Finishing off the mix was then a question of some careful fader automation, particularly on the vocals, bass, and guitar-solo lines. Given the subtle nature of many of the effects, and the importance of the guitar/keyboard balances, this was one of those mixes where it was tremendously useful to drop out the bass and drum parts temporarily, and I spent a good couple of hours working that way in order to settle all the internal details into their intended places using fine fader and EQ adjustments.

Arrangement Refinements

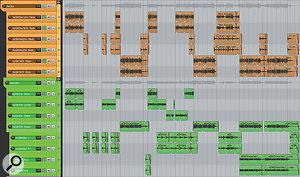

This screenshot shows the full arrangement of the acoustic guitars in Mike's final remix. The orange tracks contain sections of the original recordings, multed to allow different effects-send amounts for the verses and choruses. Below these, the green tracks are those Joe Lonsdale added to fill out the mix sound and introduce some extra performance variety.

This screenshot shows the full arrangement of the acoustic guitars in Mike's final remix. The orange tracks contain sections of the original recordings, multed to allow different effects-send amounts for the verses and choruses. Below these, the green tracks are those Joe Lonsdale added to fill out the mix sound and introduce some extra performance variety.

So much for the mix. Equally important to this month's project, though, was some judicious rearranging, because I felt that more could be achieved in this department, especially now that I had additional parts from Joe to play with. I set my sights on the choruses first, as the original multitracks all but repeated the same arrangement every time. Flexing the mute buttons helped to clear some headroom earlier on, by jettisoning the organ and backing vocals from the first chorus and adding vocals progressively afterwards: one harmony for the second chorus, two for the third, and the lead double-track for the fourth. Joe's main chorus guitar was vital from the outset for sonic reasons, so that couldn't be dropped for build-up purposes, but an additional oscillating single-note part provided a nice lift for the third chorus, and a higher-register variation was then introduced for the fourth.

By retaining too full a texture throughout, the third and fourth verses made it almost impossible to maintain momentum between the first and second choruses. Again, the mute buttons brought a solution here, silencing the drums, bass, original acoustic guitars, and electric piano in order to zoom back in on the lead vocal and a gutsy, low-register alternative rhythm part that Joe had supplied. Progressively reintroducing the missing parts during verse three then generated a nice build-up into verse four, from where the lead electric-guitar line and acoustic-guitar strums could carry the baton into the chorus.

The introduction was shortened, too, losing the opening drums section to bring the vocal entry forward by about 10 seconds. I then decided to highlight the lead electric guitar more in the mix as a melodic hook, as well as fading up the other wah-wah rhythm part only halfway though the intro section, to add something new over the chord progression's second iteration. Finally, I shuffled the vocal harmonies in Melodyne to make the three-part texture more uniform. The original lines frequently doubled each other, but not in a consistent way, so that the vocal group as a whole wasn't really holding its own against the other instruments, for me. Some of the pitch-shifts were quite large, so the backing lines sounded a bit synthetic in solo, but in the context of the full mix they were just fine.

A Stitch In Time

Project-studio work is all about making the most of limited time and money. Although it's tempting to cut corners on front-end arrangement work and engineering decision-making, this often turns out to be false economy, storing up difficulties for mixdown. This month's project demonstrates that quite clearly: a production that should really have taken no more than a day to mix, had it been more thoughtfully tracked and arranged, ended up requiring three times as long.

Rescued This Month

This month's featured project is the song 'So Easy' by Cristina Vane, a singer-songwriter originally from Paris, but now studying at Princeton University in the USA. She caught the songwriting bug in high school, recording her first five songs (including this one) in her senior year. Cristina plays acoustic guitar herself, and was joined for this recording by Sophie Alloway (drums) and Dieselle May (bass, guitars, additional vocals).

Remix Reactions

Cristina Vane: "My main problems with the original version of this song were the intro and the general momentum. The difficulty with the intro was making it interesting, but I didn't really like the wah-wah guitar line in there. As for the rest, I liked the way the full band had pulled things together, but also found that it wasn't as aggressive as I'd hoped. The song is obviously about some of the angrier feelings left after a relationship, so I wanted to communicate that more in the general vibe of the track.

"I'm really pleased with the remixed version. The change in the introduction has given the beginning of the song a bit more of a bite, which I enjoy — the solo percussion measures weren't doing as much as they could have been. The original track was a bit thin in parts before (particularly during the first verses), but it sounds a lot fuller now. The new third-verse breakdown in the guitar is one of my favourite moments: it really links up the chorus and the verses in an interesting way and the change in pace is great. The overall feel of the track is something that was really important to me as well, and I find that the new mix keeps my folksy feel but manages to ramp up the attitude a bit. All in all, it's been great hearing the new mix!”

Public Service

Many thanks to Joe Lonsdale of Joe Public Studios for recording additional acoustic-guitar parts for this month's Mix Rescue project. Unattended guitar-tracking sessions like this one start from £60 per song, and the dozen parts he provided in this instance (all of them double-tracked) would only have set you back £80, so it's a pretty cost-effective alternative to spending hours trying to fix things in the mix. For more information on Joe's range of recording, mixing, and production services, check out his web site.

Audio Examples & Project Files

In addition to the 'before' and 'after' mixdown versions, the SOS web site's accompanying Mix Rescue media page carries a number of processing demonstrations with detailed captions. As well as this, I've uploaded all the original multitrack files (including Joe's extra overdubs) and have provided the full Cockos Reaper project file for my remix, so you can scrutinise all my settings in detail.