Actor, TV host and voiceover artist Simone Kliass wearing a HTC Vive Pro VR headset at ARVORE Immersive Experiences headquarters in São Paulo, Brazil.Photo: Jason Bermingham

Actor, TV host and voiceover artist Simone Kliass wearing a HTC Vive Pro VR headset at ARVORE Immersive Experiences headquarters in São Paulo, Brazil.Photo: Jason Bermingham

The buzz around immersive visual media is creating plenty of new opportunities for those who record spoken word for a living. But how do these new jobs differ from traditional ones?

I’ve written previously in SOS about overcoming the challenges of recording voiceover in various environments, ranging from the home studio to hotel rooms, cars and even a ship’s cabin. And if I’m honest, at that time I thought I’d probably taken the subject about as far as SOS readers would find useful. But the evolution of immersive media over recent years has brought some interesting changes for voice actors and dialogue recordists.

While it’s not yet completely clear what change the metaverse (a network of interactive virtual spaces being heralded by some as social technology’s latest evolutionary frontier) might bring to the world of audio production, there’s already a definite buzz around extended‑reality technology, and next‑generation VR headsets such as Meta’s new Quest Pro and Sony’s anticipated PS VR2 have piqued the curiosity of visual content makers and consumers alike. Almost inevitably, this has brought talk of conventional VR and 360° video formats back to the table in meetings between ad agencies and production houses, and for those who make a living recording dialogue there are already new VR‑related opportunities for work out there.

In this article, with the help of several industry colleagues, I’ll explore some of the technical and artistic differences when it comes to recording and producing dialogue and narration for immersive visual media. I’m based in Brazil, which boasts a burgeoning community of immersive‑content developers. The Brazilian Extended‑Reality Association (XRBR) was founded in 2019, and in the same year a São Paulo‑based company called ARVORE Immersive Experiences took home the top VR prize from the 76th Venice International Film Festival, with their short The Line. In 2020, this experience won a Primetime Emmy for Outstanding Innovation in Interactive Media. I worked as a voiceover consultant on The Line and my wife Simone Kliass, who’s a co‑founder and the current vice‑president of XRBR, recorded the narration in Portuguese.

The actors in the 360° film Eu Sou Você (2022) wore Sennheiser EW 100 G3 wireless transmitters and lavalier mics containing Sennheiser ME 102 omnidirectional capsules.Photo: Eu Sou Você

The actors in the 360° film Eu Sou Você (2022) wore Sennheiser EW 100 G3 wireless transmitters and lavalier mics containing Sennheiser ME 102 omnidirectional capsules.Photo: Eu Sou Você

Ready, Headset, Go!

VR and 360° video are both immersive media best viewed using a headset, but there are significant differences between the two. VR is a computer‑generated digital space, in which you can actively engage with your virtual surroundings and the objects contained therein, whereas 360° video is a passively viewed spherical video image, shot by an omnidirectional camera. VR requires hardware connected to a headset with lenses, high‑resolution screens, built‑in speakers and/or a way of connecting to headphones, while a 360° video can be viewed either on a headset or a screen; really, you should only refer to a 360° video as ‘VR’ when it’s experienced using a VR or mobile‑phone headset.

The new Meta Quest Pro headset, pictured here with optional dual‑driver earbuds that offer wide dynamic range and significant ambient noise reduction.Photo: Meta

The new Meta Quest Pro headset, pictured here with optional dual‑driver earbuds that offer wide dynamic range and significant ambient noise reduction.Photo: Meta

For sound engineers, discussions of VR and 360° video tend to centre on how to achieve a hyper‑realistic binaural mix and, as with most mixes these days, the most important raw ingredient is high‑quality, reverb‑free, noise‑free source material. Ambisonic microphones like the Sennheiser Ambeo VR, Rode NT‑SF1 and Zoom VRH‑8 capsule mounted on an H8 recorder may strike you as a good place to start — surround visuals need surround sound, right? But, in practice, for anything other than capturing a rich 3D soundscape, these mics are rarely the first thing you’ll pull out of your toolkit. Omnidirectional lavalier mics, for instance, work much better for recording dialogue on location. Nothing beats a directional shotgun mic with a windscreen for capturing isolated environmental sounds or Foley tracks. And a conventional capacitor or dynamic mic is still all you’ll need for narration or automated dialogue replacement (ADR) sessions in post‑production.

In his article ‘Introduction To Immersive Audio’ (SOS January 2022), Editor in Chief Sam Inglis wrote about binaural mixes and described the pros and cons of channel‑based, scene‑based, and object‑based immersive audio formats. “Channel‑ and scene‑based formats contain fully mixed audio,” he stated, “whereas an object‑based format contains the major elements of a mix plus metadata explaining how that mix should be implemented in a given playback environment.” For VR, the object‑based format seems to work best. It allows engineers to package dialogue, sound effects and music as separate audio streams, containing metadata which helps the decoder to determine where each should sit in the spatial‑audio mix.

Head‑tracking technology makes possible some ‘audio magic’ in VR but it can also be problematic, since binaurally encoded output responds differently across devices and requires engineers to adopt a mixing/mastering workflow for each headset used in an immersive experience. Fortunately, mixing for 360° video is simpler: most of the producers my wife and I work with in Brazil prefer stereo bounces, since the viewing experience is passive and stereo ensures consistent results across multiple devices. More on this later.

The Line lets you interact with a virtual diorama inspired by 1940s São Paulo.Photo: ARVORE

The Line lets you interact with a virtual diorama inspired by 1940s São Paulo.Photo: ARVORE

Estúdio JLS

Immersive audio designer Toco Cerqueira at a Dolby Atmos 9.1.6 workstation with JBL C221 monitors, 308P MkII surrounds, and Avid S6 M10 controller. Estúdio JLS have a second Dolby Atmos mixing room under construction.Photo: Bruna MachadoTo gain a better understanding of how VR and 360° video mixes differ, especially in relation to narration and dialogue, I met up with several colleagues, as well as sound engineers Daniel Sasso and Toco Sequeira, who were responsible for the final mix of The Line, mentioned in the opening paragraphs. “When working on The Line,” Daniel explained, “we received the film’s original choro soundtrack pre‑mixed. Our job was to put the soundtrack into Unity [a real‑time development platform: https://unity.com], along with the narrations and sound effects. Normally, here at JLS we mix for TV and cinema, and our primary considerations are the sound systems and acoustics of the spaces where a mix will be heard. Since VR and 360° video are hermetic experiences, we have to be more selective about the sounds we place into the environment, especially when it comes to spoken words.”

Immersive audio designer Toco Cerqueira at a Dolby Atmos 9.1.6 workstation with JBL C221 monitors, 308P MkII surrounds, and Avid S6 M10 controller. Estúdio JLS have a second Dolby Atmos mixing room under construction.Photo: Bruna MachadoTo gain a better understanding of how VR and 360° video mixes differ, especially in relation to narration and dialogue, I met up with several colleagues, as well as sound engineers Daniel Sasso and Toco Sequeira, who were responsible for the final mix of The Line, mentioned in the opening paragraphs. “When working on The Line,” Daniel explained, “we received the film’s original choro soundtrack pre‑mixed. Our job was to put the soundtrack into Unity [a real‑time development platform: https://unity.com], along with the narrations and sound effects. Normally, here at JLS we mix for TV and cinema, and our primary considerations are the sound systems and acoustics of the spaces where a mix will be heard. Since VR and 360° video are hermetic experiences, we have to be more selective about the sounds we place into the environment, especially when it comes to spoken words.”

“Spoken words demand more attention than environmental noise,” Toco added. “For instance, if a scene is dark and you hear a cricket chirping outside, you’ll probably assume the action is taking place at night. But once you’ve made that observation, even if the cricket keeps chirping, your mind starts to focus elsewhere. Spoken words are different. Narration and dialogue give you freedom to look around as you listen, but they also require you to pay attention to what’s being said — and that requires more mental energy.”

As always, given the importance of mixing dialogue with intelligible source material, every effort should be made when on location to facilitate the engineer’s work in the studio. Here are a few quick tips that might help. First, make a conscious effort to record snippets of background noise before each take, since these audio samples can provide valuable information for the engineer to feed into de‑noise algorithms. Second, double‑ and triple‑check lavalier mic levels and placement. Finally, if working on location with unscripted dialogue, make a point of asking people if they’d be open to participating in an ADR session. You might also consider recording ADR ‘guerilla‑style’, while on the set, using a portable mic in an impromptu booth or even the back seat of a car.

Lead engineer Daniel Sasso at Estúdio JLS’s main soundstage, which boasts seats for an audience of 15, 7.1 JBL monitors, and a Digidesign D‑Control.Photo: Jason Bermingham

Lead engineer Daniel Sasso at Estúdio JLS’s main soundstage, which boasts seats for an audience of 15, 7.1 JBL monitors, and a Digidesign D‑Control.Photo: Jason Bermingham

I Am You

I also spoke with the experimental multimedia artist Tadeu Jungle, who offered some interesting insights. He sees immersive content as a vehicle for empathy, and his 360° films tackle controversial subjects such as environmental catastrophe, social inequality, and indigenous rights in Brazil. His latest production, Eu Sou Você (translation: I Am You) addresses sexual harassment in the workplace, by inviting viewers into an immersive New Year’s Eve party at the headquarters of a fictitious company. The film premiered in a São Paulo theatre where viewers were invited to come up to the stage and put on headsets.

Tadeu Jungle: Without traditional cinematic devices like transitions, panning, and close‑ups... sonic clues, and especially narration and dialogue, are so important.

“I think of the 360° format as an inverted theatre in the round,” Tadeu explained. “You, the viewer, sit centre‑stage and the story unfolds around you. This format is revolutionary, since you’re free to look around wherever you choose. But for me, the director, it poses a challenge: how am I supposed to guide you, without traditional cinematic devices like transitions, panning, and close‑ups? Even a simple cut can jeopardise your sense of presence in an immersive experience. This is why sonic clues, and especially narration and dialogue, are so important. They allow me to tell you where the story is going.”

While the shortage of editing tools in 360° video post‑production makes a director’s job harder, this results in more extended scenes, which tend to make the sound engineer’s job a touch easier; subtle changes in background noise are less perceptible when there are fewer cuts. In Eu Sou Você, for instance, scene transitions always involve a change in position and perspective, and this move from one location to another makes any discrepancy in the soundscape less jarring.

Left to right: Tadeu Jungle, Rogério Marques, and Luiz Macedo at Juke in São Paulo.Photo: Jason BerminghamAnother benefit of 360° video imagery, compared with the superimposed computer‑generated imagery (CGI) of VR, is that real‑time placement of audio elements using head‑tracking technology isn’t as vital to the immersive experience. “The field of spatialised audio is still embryonic,” lead sound designer Rogério Marques suggested. “Everything is beta, and that raises technical challenges. It’s like the old days when PC files didn’t work on a Mac — the leading goggles in the market today require different technical considerations. For this reason, with 360° video, we usually opt for a traditional stereo mix that will translate more consistently across multiple devices.”

Left to right: Tadeu Jungle, Rogério Marques, and Luiz Macedo at Juke in São Paulo.Photo: Jason BerminghamAnother benefit of 360° video imagery, compared with the superimposed computer‑generated imagery (CGI) of VR, is that real‑time placement of audio elements using head‑tracking technology isn’t as vital to the immersive experience. “The field of spatialised audio is still embryonic,” lead sound designer Rogério Marques suggested. “Everything is beta, and that raises technical challenges. It’s like the old days when PC files didn’t work on a Mac — the leading goggles in the market today require different technical considerations. For this reason, with 360° video, we usually opt for a traditional stereo mix that will translate more consistently across multiple devices.”

Narration in a spatial audio mix is rarely placed in a specific location away from the listener, but the placement of dialogue can be trickier, as the viewer can see who’s speaking. Still, we are so accustomed to hearing sound in stereo on TV and radio that dialogue in a 360° video doesn’t seem to need to be anchored to a specific location. That said, Tadeu warned against using off‑camera dialogue too often: he said that viewers feel impelled to turn and look around if they hear but don’t see somebody talking.

Luiz Macedo, who is the owner of Juke and produces Tadeu’s 360° films, pointed out that “with 360° films, the final mix should be done on headphones. I also recommend feeding the mix through small speakers that emulate how spoken‑word content will translate to the end user. There’s no point in finishing a mix that sounds fantastic on studio monitors if all that’s left when listening on a headset are harsh mids and high‑mid frequencies, with the lower mids and bass frequencies disappearing. Fortunately, narration and dialogue translate exceptionally well in headphones and small speakers.”

Rogério Marques offered me some additional insights into his post‑production workflow. “When mixing for an immersive experience, I want to reduce headroom. It’s not like in the movies, where a character can speak at around ‑28LUFS during a quiet scene. With the 360° films we work on here, I normally mix as I would for a streaming broadcast, at around ‑14LUFS. The process is very similar to a standard mix. What changes are the average loudness values and how much dynamic range I end up with — and the peak level as well.

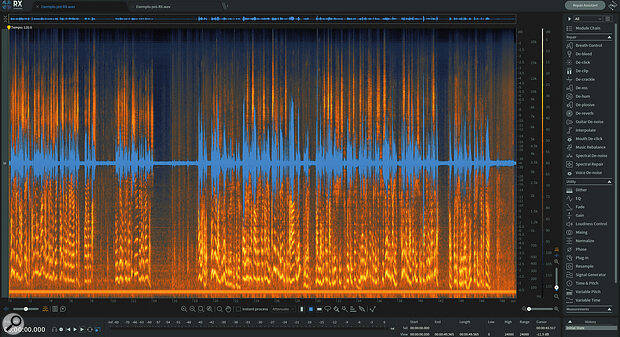

“Also, I use a spectrograph on dialogue tracks. The frequencies show up brighter according to their strength, allowing me to visually zero in on unwanted noise while keeping the integrity of the spoken‑word spectrum intact. Out in the field or on set, you may not even notice problematic noise. But here in the studio, once you start declipping, compressing, and limiting, the spirits come out of the woodwork!”

When I visited Estúdio JLS, I asked Daniel to recommend a VR experience that could help SOS readers to better understand how spoken words can add emotional depth to an immersive experience. He suggested Notes On Blindness, which uses real‑life 1980s cassette recordings to tell the main character’s story. Daniel’s point is that story always comes first, and when narration is given a context it works even when the audio quality is compromised. I posed the same question to Tadeu at Juke and he recommended Clouds Over Sidra, a 2015 VR documentary film about the Syrian refugee crisis. In this film, an English‑language narration emerges over the voice of a girl speaking Arabic, and it’s a good illustration of the power of spoken words as an immersive storytelling tool.

Post‑production ‘cleaning’ of recordings is important. These RX10 spectrograms show dialogue captured on a lavalier mic for Eu Sou Você before (above) and after (below) processing — notice how Rogério has removed some electric hum, which has a fundamental frequency at 50 or 60 Hz with harmonics above that.

Post‑production ‘cleaning’ of recordings is important. These RX10 spectrograms show dialogue captured on a lavalier mic for Eu Sou Você before (above) and after (below) processing — notice how Rogério has removed some electric hum, which has a fundamental frequency at 50 or 60 Hz with harmonics above that.

Thinking Inside The Box

My final conversation about producing narration and dialogue for VR and 360° video was at home, with my wife. Simone gives talks on voice for immersive content at innovation festivals such as South By Southwest (SXSW) in the US, and she consults on the topic for major companies in Brazil, including Meta. What makes her perspective unique is that she’s also a trained actor, experienced TV host, and veteran voice talent – meaning she understands better than most the nuances of lending your voice to an audiovisual project.

Simone visited virtual reality production company BDImmersive, based in Bristol, UK, to discuss the Portuguese‑language release of Wonderful You. Pictured left to right: Creative director John Durrant, voice talent Simone Kliass, and producer Dan Elston.Photo: Jason Bermingham“When I started training for the theatre,” Simone told me, “I learned to project my voice to the back of the house. Later, when I began recording voiceover for TV ads and radio spots, I came up with ways to cut through the noise and grab your attention in order to make myself heard. When I discovered VR, however, everything changed. I had to toss the rulebook out the window.” And the biggest change? “All of a sudden,” she said, “I was talking to an audience of one, and that one person was giving me their full and absolute attention. With VR narration, it’s just you and me inside your head. I don’t need to get your attention. I don’t need to make myself heard. You’ve already invited me into your personal space, and the more I honour that intimacy and trust, the more immersive and memorable the experience will be.”

Simone visited virtual reality production company BDImmersive, based in Bristol, UK, to discuss the Portuguese‑language release of Wonderful You. Pictured left to right: Creative director John Durrant, voice talent Simone Kliass, and producer Dan Elston.Photo: Jason Bermingham“When I started training for the theatre,” Simone told me, “I learned to project my voice to the back of the house. Later, when I began recording voiceover for TV ads and radio spots, I came up with ways to cut through the noise and grab your attention in order to make myself heard. When I discovered VR, however, everything changed. I had to toss the rulebook out the window.” And the biggest change? “All of a sudden,” she said, “I was talking to an audience of one, and that one person was giving me their full and absolute attention. With VR narration, it’s just you and me inside your head. I don’t need to get your attention. I don’t need to make myself heard. You’ve already invited me into your personal space, and the more I honour that intimacy and trust, the more immersive and memorable the experience will be.”

Simone has worked on numerous immersive experiences in Brazil, but she also lends her voice to projects that are developed elsewhere. While subtitling is traditionally used in the film industry to help films reach a wider global audience, it can prove problematic in VR and 360° video — but adding narration and other‑language dialogue tracks is pretty straightforward. Thus, these are particularly useful tools for immersive content creators. The English‑language version of The Line, for instance, was recorded by Rodrigo Santoro, a Brazilian‑born actor who has appeared in series such as Westworld. Simone also localised the narration of Wonderful You, a VR experience that takes place inside a mother’s womb. (The original narration was recorded by English actress Samantha Morton, of Minority Report fame.)

“In each of these projects,” Simone explained, “and in others as well, my job as a voice talent wasn’t simply to repeat what had already been done. Instead, I worked closely with the producers during the recording process to ensure that the content would translate to the Brazilian market and that my narration would add to the immersive nature of the experience instead of taking away from it.”

Wonderful You, a VR experience that takes place inside a mother’s womb, was voiced in English by actor Samantha Morton and in Portuguese by Simone Kliass.Photo: BHImmersive

Wonderful You, a VR experience that takes place inside a mother’s womb, was voiced in English by actor Samantha Morton and in Portuguese by Simone Kliass.Photo: BHImmersive

Mad Scientist Lab

At first glance, the ARVORE Immersive Experiences headquarters in São Paulo are what you’d expect of a cutting‑edge production company, but lurking behind the closed doors I found an R&D department that reminded me more of a mad scientist’s laboratory. An NDA prohibits my sharing any pictures here, but what I can say is that ARVORE opened my eyes to the ‘beta’ nature of VR sound.

or example, I saw bone‑conduction audio technology being used simultaneously with a pair of open‑back headphones in a room with surround monitors and a subwoofer — a setup which allows different users to absorb sound information coming from different channels through different devices. Imagine stepping into an immersive environment and ‘hearing’ an omnipresent narration vibrating from plates attached to your skull, while separate layers of 3D audio play through open‑back headphones worn over your ears, and your entire body absorbs the haptic energy of deep, bass‑rich sound emitting from surround monitors and a subwoofer set up in the room.

This particular setup may or may not end up available as a consumer product, but it is clear that ARVORE encourages all sound professionals to approach immersive sound in inventive ways, and I was left with the distinct impression that we will see some interesting developments in the future when it comes to audio for VR and 360° video!

The Tao Of VO

Mark Yoshimoto Nemcoff.Photo: Mark Yoshimoto NemcoffScriptwriters have long used the term VO, or voiceover, as shorthand for a voice track added ‘over’ picture. In a similar vein, OFF is character dialogue heard off‑screen. These spoken‑word devices are still used in VR and 360° video, of course, but as Simone’s comments also suggest, the nature of immersive content opens up the possibility of an even more intimate approach to narration and dialogue, which I call VI, or ‘voice inside’. Different from voiceover or voice off, voice inside is when the words you hear are meant to sound like your own thoughts (or perhaps the thoughts of another). The technique first caught my attention when I played the 2017 video game Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice. Its main character suffers from psychosis and, through voice acting, script development and the help of mental health specialists, the game’s developers were able to convey what Senua was hearing inside her own head. I discussed this hyper‑natural, conversational approach to voiceover with an LA‑based colleague, Mark Yoshimoto Nemcoff.

Mark Yoshimoto Nemcoff.Photo: Mark Yoshimoto NemcoffScriptwriters have long used the term VO, or voiceover, as shorthand for a voice track added ‘over’ picture. In a similar vein, OFF is character dialogue heard off‑screen. These spoken‑word devices are still used in VR and 360° video, of course, but as Simone’s comments also suggest, the nature of immersive content opens up the possibility of an even more intimate approach to narration and dialogue, which I call VI, or ‘voice inside’. Different from voiceover or voice off, voice inside is when the words you hear are meant to sound like your own thoughts (or perhaps the thoughts of another). The technique first caught my attention when I played the 2017 video game Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice. Its main character suffers from psychosis and, through voice acting, script development and the help of mental health specialists, the game’s developers were able to convey what Senua was hearing inside her own head. I discussed this hyper‑natural, conversational approach to voiceover with an LA‑based colleague, Mark Yoshimoto Nemcoff.

“A couple of years ago,” Mark recounted, “I won an audition for what I thought was a video game job but turned out to be a VR experience where you’re running from dinosaurs; like a Jurassic Park thing, but in a playful way because I think it was for 10‑year‑olds. And I remember the note from the client was that I was essentially the voice inside the participant’s head. It wasn’t like I was some virtual assistant like the Cortana hologram in the game Halo, popping up every so often with instructions. I was a helper, but I was also, in a way, prompting what their ‘thoughts’ were, like “Wow, it’s really high up on this ledge. Need to be careful.” It took me a little while to wrap my head around it. My instructions had to sound like I was sharing information and my ‘thoughts’ had to sound totally off the cuff, which opened up the door for some stammering, elongated pauses, etc.

“Then I had this total epiphany. In this VR experience, I had to play the part of both the conscious mind and the unconscious mind. As the conscious mind, I had to seemingly tell you things in the same way you’d talk to yourself: “Ok, go left up here... now go right.” But then, I’m also the subconscious mind because even when I’m reacting off the cuff — “Oh no, it’s really dangerous up here!” — all that dialogue has to come from a place that not only feels involuntary but also like it’s coming from the well of fears and anxiety inside you. I’m not talking to you. I’m not talking with you. I’m talking as you. Now, subconscious emotional manipulation is kinda what we do every day for any kind of narration, but it’s how you have to seamlessly blend it from ‘urging’ to ‘experiencing’ an action, and rationalising it through inner dialogue in real time.

“We all do those jobs where we are the ‘internal voice’ doing a Nike “just do it” kind of inner monologue, to inspire greatness in the listener. That’s the primal voice of my Id. But, with VI, I’m voicing the Id, the Ego and the Superego all at once. And, because I’m disembodied and speaking to the participant, who retains their cognitive powers, I serve as not only the voice inside your mind, but as your guiding light. Now, stop to think about that for a moment. I don’t control you. I seem to know you. I know what you’re supposed to be feeling because I know what’s about to happen. Yet, I leave your actions up to you to ultimately decide your path. You are immersed in a digital microcosm, liberated from the physical world with only my voice to reassure you. It transcends VO as we know it. It transcends acting. It’s a function of connecting yourself to the participant on, dare I say it, a spiritual level.”