Producer Tommaso Colliva (left) and drummer Alex Reeves.Photo: Richard Ecclestone

Producer Tommaso Colliva (left) and drummer Alex Reeves.Photo: Richard Ecclestone

Everyone agrees that when you’re tracking drums, the room makes a difference — but with so many other variables in play, identifying its specific contribution can be tricky. Enter producer Tommaso Colliva, drummer Alex Reeves, and a unique experiment...

It’s not often that the worlds of studio recording and celebrity chefery intersect, but such was the case for Tommaso Colliva, the Italian-born, London-based producer and engineer best known for his long-running collaboration with British rock trio Muse.

“In recent years there has been this thing about chefs and cooking being a big thing. It didn’t used to be like that 20 years ago!” he says. “I was being interviewed on a TV show in Italy with a very important chef, and before the interview, we had this good hour's chat about creativity. He told me something that I didn’t know, which was that some chefs train themselves by eating raw ingredients, just to understand how one thing can influence everything. So you taste different kinds of pasta with no sauce, or different kinds of salt. To me it sounded crazy, but it kind of makes sense because these are all pieces of a puzzle that you’re then building up, so you need to isolate the variables.”

Food For Thought

This idea clearly struck a chord with Colliva. Having “grown up”, as he puts it, as an assistant engineer at prominent Milan recording studio Officine Meccaniche, the last 10 years have seen the freelance Colliva combine his work with Muse with a wide variety of other endeavours, including producing leading Italian indie band Afterhours and his own side-project Calibro 35, an instrumental funk band inspired by Italian B-movie soundtracks of the 1960s and ‘70s. As he has gradually moved away from pure engineering assignments and into the overarching role of the producer, Colliva has found himself increasingly interested in understanding all the variables.

“As a producer, I need to know every available tool,” he says. “I need to know how much a set of drums in one room sounds different to another set of drums in another room. In order to be able to predict a little bit and to pick the right choice for everything, I need to know the tools. But while it’s easy to change a microphone, it’s not easy to change a room. I’m flicking through presets every day, using different plug-ins or shooting out different vocal mics every time I record vocals. But changing the room the drums are in? You just never do that. It’s very rare.

“Usually how it goes is that the team in charge of doing an album chats about the album and how it should sound. Then, based on that plus the budget you have, you pick a studio. You pick a studio, you pick the instruments, you pick the microphones — you pick a lot of things based on what you think is going to work. But while it’s kind of easy to build your knowledge on certain aspects, like how this or that kick-drum mic sounds, or this drum head or this kit — with experience and repetition, you can pinpoint the variables — with the room, it’s a bit tricky because every time you’re experiencing a very unique moment.

“For example, I’ve recorded two Muse albums at AIR Studios. That probably means about 25 different tracks, so you might say that I have experience of recording drums in that room. But then, I’ve never recorded a jazz album there. I’ve recorded quieter songs, but then in those cases we changed the drum kit and we changed the mics because we were after a different sound.”

Key to Colliva and Reeves’ experiment was devising a miking setup that was precisely repeatable. To that end, a single Neumann U67 was used as an overhead mic, with a Neumann KU100 binaural dummy head as a close room mic.

Key to Colliva and Reeves’ experiment was devising a miking setup that was precisely repeatable. To that end, a single Neumann U67 was used as an overhead mic, with a Neumann KU100 binaural dummy head as a close room mic.

You can see Colliva’s point. While the importance of the space you record in is something we all understand to be fundamental, the ‘sound’ of a room is surprisingly difficult to pin down, being very much dependent on what you’re recording and what you use to record it. In order to isolate this most slippery of variables, Colliva and in-demand session drummer Alex Reeves (Bat For Lashes, Guy Garvey, Dizzee Rascal) decided to conduct an unusual experiment. Over two days, the pair recorded the drums parts for three different songs in six different studios (and a living room), changing the space while keeping everything else consistent. That meant having the same microphones positioned identically in relation to the kit; the same preamps and converters; the same drum kit; and the same drummer, delivering what was as close as possible to the same performance.

Another view of the miking setup.

Another view of the miking setup.

Breaking With Tradition

The impetus to conduct this experiment came out of a previous project that the producer and drummer had worked on together. In 2015, as an offshoot of the Red Bull BC One B-boy breakdancing competition, Red Bull asked Colliva and his colleague in Calibro 35, Massimo Martellotta, to create an album of 20 new, live-recorded hip-hop breaks, and Colliva called on Reeves to supply the all-important beats. Though he’s best known for his work with one of the biggest rock bands in the world, the album — titled Around The World In 20 Breaks — was familiar territory for the Italian producer.

“I have a hip-hop background,” Colliva explains. “I grew up as a B-boy DJ when I was a teenager, so I know the era quite well — or, at least, I used to know it quite well — and the Red Bull project brought me back to actually revisiting the whole catalogue. It made me ask the question: what are breaks about? They all sound so different, but they’re so consistent, in a way. The all appeal to the same thing, but they have huge differences in sound, especially the drum sound. The usual thing that you want is for an album to be very consistent: the drum sound is the same throughout the whole album. But when we embarked on this album of 20 breaks, we wanted the drum sounds to change a lot from song to song. We needed a very dry sound, then a very rock sound, then a very crunchy, lo-fi sound for other songs. From an engineering perspective, that job was quite interesting.”

“We wanted it to sound like 20 different breaks recorded at different times in different studios by different drummers around the world,” Reeves adds, “so variety was key, but we only ended up using two or three different studios. So in order to get that variety we changed the drum kit, we changed the miking, where we put the drum kit in the room, and so on. And it was drastic; the changes were huge. But it was also clear that one drum kit in one room sounded very similar to another drum kit in the same room played by the same drummer. To get that variety, I was changing the way I hit the kit and trying lots of different things. But we had the idea about halfway through: what would it be like recording the same track in lots of different rooms?”

“Then we looked at each other and said, ‘Why don’t we do it?’,” says Colliva. “Because how do you actually experience how much the room changes the sound? The only way is actually to take the same player with the same drum kit, playing the same songs, recorded with the same microphones, and go to different studios. It’s the only way you can do it. In the real world, it’s pretty rare that you’re allowed to record the same song twice in different studios. Usually it’s a case of, ‘We’ve got this studio, we need to record these songs, let’s get it done as best as we can.’ But even when you have the possibility of saying, ‘Let’s go to another studio and see how it sounds over there,’ usually it’s because you’re not satisfied with the sound you had in the previous studio. So you start changing variables, and you end up kind of chasing your tail. We all change room, then I’ll change microphones, the drummer will change drums and probably the arranger will change the drum pattern. Even when you change even one variable, it’s very hard to compare.”

Minimise The Variables

Colliva’s answer was to take an ultra-scientific approach, attempting to eliminate as many different variables as possible in order to hear, hopefully in isolation, what each room was doing to the drum sound. That meant finding a way to keep everything but the room absolutely consistent.

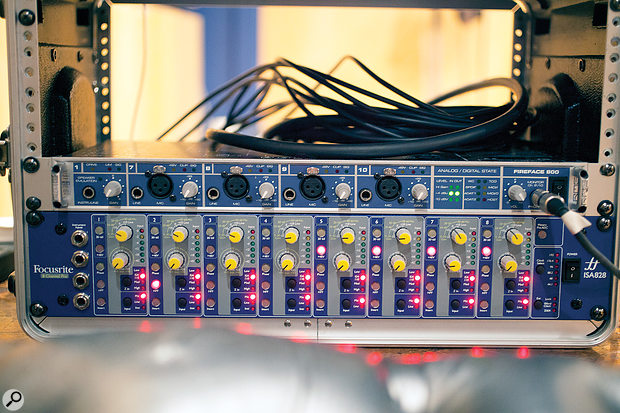

“It took me a couple of weeks to figure out how to do that, and then one day to put everything we would need together in a tidy rack,” Colliva explains. “All we asked for from the studios was power, because I had my mics, my rack, my cables, headphones and everything. As soon as you go down into the details, you become a little bit paranoid, so we didn’t want to change the mic cables, or the wiring, or anything. Everything was supposed to be as consistent as possible.”

Gain settings on the Focusrite ISA828 preamp were preserved throughout the experiment, except on the PZM mics which varied in level depending on the size of the room.

Gain settings on the Focusrite ISA828 preamp were preserved throughout the experiment, except on the PZM mics which varied in level depending on the size of the room.

That rack contained a Focusrite ISA828 eight-channel mic preamp and an RME Fireface 800 audio interface, connected to a laptop running Pro Tools 11. When it came to mic selection, the priority was to find a consistent, repeatable setup, rather than to achieve the most appealing results, as Colliva explains: “We were not trying to get the best possible sound, or the best possible takes. We knew that we wanted to be in and out of each room pretty quickly, so we needed to keep it simple. And we knew that the more mics you have, the more variables you have, and we were trying to minimise variables.

“At the beginning, the original idea was to go in with only the [Neumann KU100] binaural head, at a fixed distance from the kit. Arguably, that’s the best way to get a feeling of the room. It wouldn’t sound perfect on any record, but it will give an accurate perception of how the room sounds. Then we started thinking: ‘If we’re in the studios anyway, let’s experiment a little bit more.’ So we added the close mics — kick, snare, floor tom — and one mono overhead. We didn’t want to use stereo overheads because the placement could be a little bit tricky to replicate accurately. You could have a stereo mic and that would make it a bit easier, but to have two mics pointing exactly the same you go down a slippery path. But a mono overhead is really easy to measure.”

Alongside the Neumann binaural head, for the close mics Colliva opted for the industry-standard selection of a Shure SM57 on the snare, a Sennheiser 602 on the kick and a Sennheiser 604 on the floor tom, with a Neumann U67 for the mono overhead. In addition, Colliva decided to use a pair of Crown PZM mics positioned as far away as possible in order to capture the room sound at its most exaggerated. Here, achieving consistency was essentially impossible. To augment the overhead and room mics, industry-standard close mics were employed, in conventional positions. Tommaso Colliva was surprised at how little the room influenced the sound captured by these close mics.

To augment the overhead and room mics, industry-standard close mics were employed, in conventional positions. Tommaso Colliva was surprised at how little the room influenced the sound captured by these close mics.

“The placement of the PZMs was a subjective decision, but in each case it was the farthest possible wall from the drum kit,” he explains. “Most of the time you end up putting the drum kit on one side of the room. It’s fairly rare that you put the drum kit right in the middle of the room. So we put the PZMs on the opposite side of the room from the kit. But that varied a lot. In some of the big rooms like AIR, Snap and RAK, they had these huge glass windows between the control room and the live room, so the only option for us was to fix the PZMs on the glass. Whereas in RAK Studio 2, you have this weirdly shaped double-height room, and we ended up taking a ladder and putting them up on the higher section of wall. In my studio, we just put them on the wall opposite the drum kit where there’s some absorption going on. So that really changes things. That’s where you discover that sometimes it’s really tough to minimise variables.”

How Does It Feel?

Perhaps the most obviously tricky variable to control is the drummer’s performance itself, with where, how and how hard each kit piece is struck all affecting the sound, not to mention broader musical variables like timing, dynamics and overall feel.

“The possibility of collaborating with Alex was really important to making this idea actually possible,” says Colliva, “because I could see him being so reliable and so consistent. He’s so good, he’s going to play exactly the same, or as close as possible, in each studio. He had in-ear monitors, so he was playing to a track. The mix of his in-ears was controlled by RME Totalmix software, so it was exactly the same in each room. We also kept the gain of all the mics, except for the PZMs, exactly the same. We had to change the PZMs because their distance from the kit changed so much from studio to studio — from a booth to Studio 1 at AIR!”

The drum kit itself was also carefully chosen. “From an engineering perspective, I always tend to think in terms of a priority list,” says Colliva. “For example, when you’re recording drums, to me, the drums come first and drum heads come second. Then you have the microphones, and then you have mic pres and converters and all the rest. Of course, it’s best to keep everything to as good a standard as possible, but sometimes if you have a shit instrument it doesn’t make that much of a difference if you change the converter!”

Reeves chose a Sonor Vintage Series kit, both for quality of sound and consistent performance. “I tend to record on vintage kits,” Reeves explains, “and for a long time I’ve been trying to find a modern drum kit that I can properly take out on the road and chuck around, one that is consistent in the way that vintage drum kits frequently aren’t. I find that most modern kits just haven’t got the real low-end stuff; everything sounds pokey and middle-y. And this one doesn’t, it sounds big and round and beautiful. To me, it’s the perfect balance between old and new: the beefy, low and rounded sound of a vintage kit, with a little extra attack and poke like a modern kit.”

The pair selected three different tracks that would showcase a range of styles and dynamics, and for each one Reeves used a different snare drum. The first was a funk break taken from the Red Bull album, the second was a track by alt-folk singer-songwriter Lotte Mullan, and the third was a leftfield pop number by Hazel Mills of post-punk synth four-piece Adding Machine.

“For the Red Bull track, I used a steel Sonor Ascent snare, tuned tight like old funk snares,” Reeves says. “We chose Lotte’s track because it was quiet. I was playing with brushes and using an early-1900s single-ply maple drum with gut snares. Generally, the louder you hit the more you’ll hear the room, but that quiet track was really different in all of them. The Hazel Mills track was taken from a session I’d done a few days before. That track just stuck out as being something that had quite an unusual drum part, but quite loud. I could hit quite hard and I could use a certain style of playing that wasn’t going to be the case with the other two. For that I used a maple Sonor Hilite snare, tuned very low and heavily dampened with Moongel, with the snare loose.”

Finding Space

The next hurdle was to persuade studios to take part in the experiment. Colliva was pleasantly surprised to find no shortage of willing venues, including some of the biggest studios in London. The final list of candidates featured two large live rooms (AIR Lyndhurst Studio 1 and RAK Studio 1), two medium-sized rooms (RAK Studio 2 and Snap) and two small rooms (Jam Track Central and the overdub booth at Colliva’s project studio, Toomi Labs). A seventh venue — the living room of Colliva’s own house — was added on the spur of the moment.

“On the first day, we were a bit surprised that we could actually do three studios in one day,” he explains. “We were in and out of each studio in about three hours. We had kept my overdub booth as an extra if we had time, so we did that too. On the second day, we had just finished at Snap and it was pretty much lunchtime. I live just around the corner from Snap, so we decided to have a quick pasta at my place. We started looking at the big, weirdly shaped living room and we thought, why not? So it was completely improvised but I’m really glad we did it. To have in the two weirdest rooms — my small booth and my living room — has proven to be really beneficial in terms of having a comparison to real-world conditions.”

According to Colliva, the most important difference between the proper studios and spaces like his living room lies not in the sound of the room as-is, but in what will happen once you start to mix.

“All of the studios we went into sounded really good and gave results that were not only good but that I could see from an engineering perspective would be tweakable,” he explains. “For example, you can compress them. From a producer/mixer point of view, I’ve developed this thing about predicting how a track will compress. What will go on when I compress? Sometimes you get those tracks where they sound OK but then you start compressing them or EQ’ing them and it just opens up a can of worms: resonances, weak sounds, thin sounds. And it’s pretty clear that, for example, with my living room it will be hell. It has a sound and it doesn’t sound bad — it’s weirdly shaped with no parallel walls, so that helps it not sound like a shoebox — but at the same time, you can tell it’s going to sound shit if you compress it! It’s going to sound really wishy-washy, really resonant. You’ll be notching down frequencies a lot just to make it sound reasonable. But AIR, RAK, Snap, even the smaller room at Jam Track Central: they’re all very useful. I can see why we do records there! If you switch from my living room to AIR Studio 1, you can see that, while the perceived size is not so different, one will compress well but the other will be a pain in the arse.”

One additional variable that had to be addressed was where in each room the drums should be situated. Here, Colliva took guidance from the studios themselves. “We asked the people who worked in the studios where the usual spot for drums is in the room,” he says. “And it was pretty consistent — at one end of the room, because you want to use the whole depth of the room, and not too close to the walls, because you will get too much build-up of resonances. I cut my teeth at a big studio in Italy, and I learnt from the other side that there are reasons why drums sound good in a particular place! Sometimes you will experiment with position to find something different, but the people who work in a studio and have to deal with that room every day, they will know where a drum kit is supposed to go.”

Size Matters

“We were not expecting to get so much help from studios, particularly well-known studios,” Colliva says. “The fact that we could go to two of the biggest rooms in London — AIR Studio 1 and RAK Studio 1 — was fantastic. They are just... big! They sound different, because AIR is kind of completely reflective. It has very little absorption. It’s designed to be used by orchestras as well as bands, so you need the sound to build up a lot. That’s why they also have a lot of panels, the movable walls, the carpet option. It’s not that they know they need to deaden the sound, but they know they need to have the option. Kind of the same concepts apply to RAK Studio 1. They have folding walls that can be used to split the room in two and things like that. But RAK has absorbent panels on the walls so it sounds a little bit drier, but you can still feel that it’s a big room. If you listen to the recording you can hear that AIR is bigger, but you could kind of think they’re similar-sized.

“The same thing happens between RAK Studio 2 and Snap, which sound quite similar. Again, they are similarly sized; you would put them both in the medium-sized room category. I really enjoyed using both rooms, but that’s maybe because I can see genres that I’m doing fitting well with those rooms. My feeling is it would be really easy to do in-your-face and punchy drums at RAK Studio 2, while Snap felt a little bit more balanced and controlled, more mellow and comfortable if you like. The good thing is I’m sure both will be highly tweakable when choosing the right drums, right mics and mic placement for each song. That’s what good studios are, after all!”

In AIR Studio 1, Colliva had the opportunity to experiment with the studio’s movable panels. By positioning gobos above and on three sides of the kit, he created a temporary booth around the drums, open on the front. “We kept the kit exactly as it was, the microphones exactly as they were, and we just put panels around and above the drum kit, just to deaden the sound as much as we could in a big room. Comparing the binaural head at AIR with and without panels, there’s a huge difference. With the PZMs you can also really hear the difference. So you can really see how panels affect the sound, if they are around the mic or even if they’re not. They change the whole resonating factor of the room a lot.

“There’s an expression in Italian, ‘discovering the hot water’. You discover something that you think is amazing, but in fact it has been discovered ages ago! Doing drums in a small room but keeping the door open has been around since Led Zeppelin. They were the first ones panelling the drums in a big room just to have the best of both worlds. Still, I was not expecting that the sound could be changed so much just by moving some panels. That really made a huge difference. To my ears. it’s remarkable how AIR Studio 1 with and without panels sounds so different, much more different than RAK Studio 2 and Snap, which are completely different spaces.”

In the more modestly sized rooms — the small drum room at Jam Track Central and Colliva’s own overdub booth — the build-up of low frequencies was the most prominent feature. Once again, the perceived size and actual size of the rooms did not necessarily correspond.

“I was not expecting the room at Jam Track Central to sound much bigger than it actually is. In practice, that’s actually a good thing. It allows them to produce tracks in house over different genres without the need to go somewhere else every time. My booth, on the other hand, was never intended to house drums. It’s big enough to squeeze a drum kit in, but I rarely do that. I use it for vocals and overdubs, and to experiment with guitar amps and bass. I would say that pretty much all of the rooms gave us good, tweakable results.”

Flexible Friends

When asked to pick a favourite, Colliva leans towards AIR Studio 1, particularly given the flexibility afforded by its movable walls and panels. He’s quick to acknowledge, however, that this is as much about practical considerations as sound alone. “I realise how much of a ‘producer’ comment that is,” he says, “because if a record label asked me to book a studio today, I know that if we book that room I will be able to come up with a good sound. In large rooms like Studio 1 at AIR and Studio 1 at RAK you can see the possibility of actually changing the room sound a lot. But, in fact, all the rooms made sense. As a producer, I want to know what the best option is but it’s not a given that that will be the best option every time. There are a lot of variables and you have to pick the right hammer for the right nail. I think the whole experiment kind of reinforced this whole concept.

“I would actually be surprised to go into six different rooms and say, ‘This one is clearly the best.’ I had my favourites depending on which song we played, or the options the rooms provided — like, I know if you go into this or that room you can get six or seven different sounds — but there’s simply no right or wrong. Well, there are some wrongs, but there’s no best and worst! The only two rooms that were a bit of a one-trick pony were my booth and my living room. They were the only ones where I know you can’t do certain things.”

Toomi Labs is Tommaso Colliva’s studio-cum-private playground.Photo: Eugenio Vasdeki

Toomi Labs is Tommaso Colliva’s studio-cum-private playground.Photo: Eugenio Vasdeki

Alex Reeves also feels that the ‘ideal’ room very much depends on the material in question. “Of the three tunes we recorded,” he says, “I definitely felt like some of them just sounded right in certain studios. None of them sounded wrong in any of them, but some of them sounded better, to my ears as a musician reacting to my situation in the rooms.

“In Tommaso’s room,” he adds, “you really notice that the bass is extremely present. The bass drum sounds just incredible — possibly a bit much, actually. It felt so different to play in that room because it was so bassy and boomy, but for the quieter stuff that was just great. You know the loudness button you get on old amplifiers to boost the bass when you’re listening at low volume? It really felt like the same thing, especially on Lotte’s track where I was playing softly and everything was a bit more composed. On that track, I was letting the bass drum beater come off the head as opposed to the louder stuff where I’m just slamming it in. And it was beautiful in that room, it really suited it.

“Anyone can listen to the takes and make up their own mind about what sounds better or worse for each track, but you’d probably be surprised as to which studio you’re in. The more expensive studio doesn’t necessarily give you the right drum sound. It’s not a question of better or worse, but what suits the individual track.”

The small drum room at Jam Track Central.

The small drum room at Jam Track Central.

The Human Element

Both producer and drummer emphasise that the size, sound and feel of a room have a big impact not just on the sound of a recording but on the musicians themselves and the way they perform. For Alex Reeves, performing the same tracks in different studios in quick succession really brought home how much influence the playing environment has on him.

“I knew that my job was to keep my performance completely consistent,” Reeves says. “I had to hit the drums in the same way, I had to make them sound the same, I had to make the tracks feel the same. With that in mind, we adjusted my in-ear monitor mix so that I wasn’t hearing any of the room. I was just hearing the close mics and I had the same mix coming to me. But even so, it sounded so different in each space that it couldn’t help but influence the way I wanted to play.

“We chose three simple songs with simple drum parts so that there would be very little variation. I was obviously trying not to take artistic licence with what I was playing, but what was interesting was that I really wanted to, because each room and each situation was making me feel a slightly different way. In some of the rooms, for instance, I really wanted to go for it on the ending of the louder Hazel Mills track. If I was being asked to play a session for that track, I would have made it more exciting, because I was in a room that excited me — I had a sound that I could play off, and that was exciting me.

“My drum teacher, Bob Armstrong, always told me to play the space I was in, and I’ve always gone by that. You don’t want to be smashing everyone’s ears to pieces in a tiny club, but if you’re playing in an arena or a stadium, it almost doesn’t matter how loud you’re playing. The same goes in the studio: you play the space. The space feeds back to you and you feed back to it. It’s a conversation between the musician and the space the musician is in.”

Experimenting with the movable panels at AIR proved a revelation for Reeves as well as for Colliva. “It completely changed the way I played. The one that changed the most was Lotte’s track, where I was playing more quietly. Everything suddenly felt really different, I could hear things in a completely different way. The way the drums sounded was night and day, with and without the panels. It is a really tried and tested technique in a bigger room like that, but just changing a couple of panels, like taking the roof off or opening up one side or the other — that immediately affected the way I played and the sound of the track.

“As musician, you’re constantly listening to the room, and the feedback that you get from your immediate surroundings will rule everything. To take an extreme example, the difference between playing at Pizza Express in Soho and the O2 Arena on the same kit — which I’ve done — is massive. In an arena you get no feedback from the room apart from what’s in your monitors. Unless you’re hitting really, really hard, the room does not react to you. Whereas, in Pizza Express, the room immediately reacts to you and you react to it. Again, it’s a conversation between the musicians and the space that the musicians are in.”

Even the experience of hearing the room influence his playing, however, didn’t prepare Alex Reeves for the effect the spaces would have on the finished recordings. “We knew that each of these studios was going to sound different, but just how different they were was astonishing. I was amazed at how much the sound of the drums in a different room completely changed the entire track. Playing at the time, obviously I was aware that there were changes, but listening to each track in six different studios side by side, it’s really extreme. I think it’s one of the things that will change a track the most. If you’re using real drums, it will change everything according to what room you’re in. That’s what shocked me.”

A seventh venue — the living room of Colliva’s own house — was added on the spur of the moment.

A seventh venue — the living room of Colliva’s own house — was added on the spur of the moment.

Lessons Learned

Apart from the sheer extent of the influence of the room on the sound, are there more specific lessons to be learned from this experiment? Tommaso Colliva certainly thinks so, one of them being that there was relatively little variation in the sound of the close mics. “The sound of the close mics is actually pretty consistent,” he says. “Listening to the kick drums, you would say they’re fairly similar from room to room. If you change any other variables — the kick drum mic, the drum head, the beater — that will change so much more than changing the room. The floor tom is the same. That surprised me. After this experiment, I know that the close mics are not going to change that much if we change the room. So muting the overheads or muting the room mics may give you an idea of: is it actually the kit that is our problem, or is it the room that is our problem? So what do we tweak? What do we move? How do we approach this?”

From a producer’s point of view, it forced Colliva to rethink the process of fine-tuning a drum sound. “After this, I will definitely think about panelling the drums in a very different way. Every time you think about changing something, it’s either because you’re not satisfied with what you have, or because you’re looking for something different. I know now that I can keep everything exactly as it is and just involve panels and that will make a huge difference. It will allow me to compare things more quickly without having to strike down the kit and change microphones as well. It’s a starting point, at least. If we’re not sure, if it sounds too washy, let’s try building a small booth out of panels and then see if that still sounds too washy, before we dampen the drums, before we change the miking, before we change anything else.

“I think investigating single variables one by one is really beneficial. It’s good to focus your attention on one element at a time, because sometimes we are a little bit too much dragged into thinking, ‘It’s not working, I need to change everything!’ Of course, every one of us has a point of view, and we’re used to thinking about the variables that we can control. So, as an engineer, you think about microphones and mic pres and converters and the software you’re using. A drummer will think about the drums, drum sticks, the heads. And sometimes it’s difficult to puzzle everything together. I guess that’s what a producer is for: to puzzle things together.

“For me, as a producer, the studio you pick is really important. There is a beautiful song by Ani DiFranco called ‘Fuel’, where she says, ‘They used to make records as a record of an event, the event of people playing music in a room.’ And that is true. They used to do records like that, and we’re not so used to that any more. I’m not too dogmatic about anything, but for me, it’s always a good starting point. Let’s make the music happen in a room kind of as close as possible to the final result, and we’ll try to capture that. Then we do the hyper-reality things — we focus on sounds, we make the drum kit really punchy, that kind of thing — but it needs to already be there. I feel you can’t reinvent anything. You can optimise and you can make it more real than real, but at the same time it’s good to start with the drums sounding roughly as they are supposed to sound on the final record.”

That’s as good a final word on this experiment as we can find, but you get the sense that Colliva may have only just begun. “Now I feel like it would be interesting to replicate this experiment looking at the other variables in a scientific way,” he says. “Mic selection, kit pieces, drum heads — I think that the heads are highly underestimated in the recording process, but they make so much difference...”

The Studios: AIR Lyndhurst Studio 1

Though not on the same scale as the world-famous Lyndhurst Hall, the live room of AIR Studio 1 is still very large by any measure, offering 140 square metres of floor space. Designed to accommodate orchestral ensembles, it’s a relatively live-sounding space, with wooden floors, minimal absorption on the walls, and large windows to let in natural light. But it’s not just an orchestral room: numerous bands including Coldplay, Mumford & Sons and Muse (with Tommaso Colliva) have chosen to record here. A system of movable walls makes it possible to split the room into separate sections, while carpeting, movable screens and gobos provide further potential to customise the space.

“I have been at AIR quite few times with Muse,” says Colliva. “We recorded most of The 2nd Law there and I come back every now and then. One thing is for sure: it’s always a pleasure to be back in such a nice space. We decided to do a first run through all songs with a completely open room and then, keeping the mics exactly where they were, move some absorbent gobos around the drums to recreate a small room within the large space. The difference was huge. The sound of the kit mics — including the binaural head — was much more focused, while the sound captured by far room PZMs also changed while still maintaining that larger-than-life thing.”

The Studios: Toomi Labs Overdub Booth

Also based at Palm Recordings, Toomi Labs is Tommaso Colliva’s studio-cum-private playground. Comprising a mixing room and an adjoining recording booth, he uses it to mix records, record overdubs, develop artists and albums, and experiment with sounds.

“My booth was never intended for recording drums, but it’s definitely big enough to squeeze in a drum kit!” says Colliva. “Since moving to Palm Recordings, I’ve used it only twice to record drums — once for a deep funk/garage-y band and once for an electronic-based album — and have been surprisingly happy with the results. Out of six walls, three are absorbent (the ceiling and two vertical walls) and three are reflective (the floor, the wall with a window through to the control room and a wall with a wooden diffuser). There are also three bass traps hung in the three accessible corners. The sound is extremely tight if not on the dead side, with very little in the way of reflections and a noticeable build-up on the low end. It does not surprise me that it was good for garage funk and electronics with live drums.”

The Studios: RAK Studio 1

Founded in 1976, RAK Studios has long been a first-choice recording space for some of the biggest names in rock and pop, from David Bowie to Adele. Of the four studios within the complex, Studio 1 is the largest. Its 100-square-metre live room is rectangular, with a wooden floor and absorbent panelling on the long parallel walls designed to produce a space that sounds big and live yet well controlled. Like AIR Studio 1, this studio features a folding wall that can be used to divide the room in two, plus a range of movable gobos.

“It’s easy to hear that there are no nasty resonances, and the decay is very balanced over the frequency spectrum,” says Tommaso Colliva. “That makes it easy to record using room mics and over-compress them without bringing up too many unwanted artifacts. If you add in the folding wall and the absorbent gobos, it’s a very flexible recording space.”

The Studios: Jam Track Central Drum Room

Based in the same Palm Recordings facility where Tommaso Colliva has his own project studio, Jam Track Central produce backing tracks and other tuition material for guitarists.

“The Jam Track drum space is smaller than other studios we went to, but big live rooms are, unfortunately, pretty rare these days,” says Colliva. “There’s not that much absorption on the walls, with one QRD [diffuser] on one side and two windows facing another booth, and the control room on the others. I was surprised how much bigger it sounded when recorded compared to the real dimensions. Not having too much dampening on the walls is surely one of the key factors. I can see it being very flexible to record drums for different projects without needing a much bigger space.”

The Studios: RAK Studio 2

Unique and unconventional, RAK Studio 2 features a control room on a mezzanine that hovers over the 40-square-metre live space. The end result is a medium-sized room that is half single-height, half double-height, with a drum riser located in one corner of the double-height section. All wood panelling and odd angles, this an unusual and lively place.

“For me, it’s more reminiscent of ’70s American West Coast studios than of British orchestral rooms like RAK Studio 1, Abbey Road or AIR,” says Tommaso Colliva. “There is definitely less absorption going on on the walls compared to Studio 1, but there also seem not to be any parallel surfaces. That translates to a pretty different sound: more live and punchy, easily transformed into something more aggressive and in-your-face.”

The Studios: Snap Studio 1

A relatively young facility, Snap Studios features (alongside a mouthwatering array of vintage equipment) a 55-metre-square live room carefully designed to offer desirable acoustics. The floor is reclaimed oak while the long parallel walls of this rectangular room feature wood panelling on one side and absorbent panelling on the other.

“This is quite a new room on the London studio scene and it’s amazing,” says Tommaso Colliva. “It’s built like back in the day but without the downsides of being an old place: obsolete wiring, bad soundproofing, inefficient AC and so on. This is a very nice medium-sized live room with a good blend between absorption and reflections, so you can keep the sound focused while having it big and spacey at the same time.”

The Equipment

Drum kit

- Sonor Vintage Series 22-inch bass drum and 14-inch floor tom.

- Sabian Big N Ugly Phoenix ride cymbal and hi-hats.

- Sonor Ascent 14x6 steel snare (‘You Know How To Rock’, written by Massimo Martellotta, performed by the Cypher Ensemble).

- 1900s single-ply maple snare drum with gut snare (‘Burning Up’, written and performed by Lotte Mullan, courtesy of Reverb Music).

- Sonor Hilite 14x6 snare with Aquarian Satin Finish head (‘A Father’s First Words’, written and performed by Hazel Mills and TJ Allen).

Microphones

- Kick drum: Sennheiser e602.

- Snare drum: Shure SM57.

- Floor tom: Sennheiser 604.

- Mono overhead, directly above snare drum: Neumann U67.

- Neumann KU100 binaural dummy head, 160cm above floor and 150cm back from kit.

- Crown PZM 6D pressure-zone mics attached to far wall.

Recording chain

- Focusrite ISA828 preamp.

- RME Fireface 800 interface.

- Avid Pro Tools 11 (24-bit/44.1kHz WAV session).

Sound & Vision

This article is accompanied both by audio examples illustrating the way in which the different spaces influenced the overall drum sound, and by a video feature by film-maker Erica Gianesini.

Audio Examples

These audio files accompany the cover feature in SOS September 2016. Drummer Alex Reeves was recorded in seven different live rooms, ranging from AIR Studio 1 to the living room of producer Tommaso Colliva. In each case, four files are provided:

- A full mix of the entire track.

- A full drum mix.

- The room recording from a Neumann binaural head.

- The signal captured by a pair of pressure-zone microphones on the far wall of the studio.

Note that there are two sets of files from AIR Studio 1. For the second set, Tommaso used the studio’s acoustic screens to create an enclosure around the drum kit, with radically different results!