Looking at the contents of the effect track using Cubase's List edit, you can see how simple it is to automate your effects. Here there are two effect units, one each on MIDI channels 15 and 16. Notice the program change messages at the start of the song. The SysEx messages are used by my Midiverb 4 to control output volume, and my Boss SE70 has its output level mapped to aftertouch, which allows me to draw in a short effect volume fade at the end.

Looking at the contents of the effect track using Cubase's List edit, you can see how simple it is to automate your effects. Here there are two effect units, one each on MIDI channels 15 and 16. Notice the program change messages at the start of the song. The SysEx messages are used by my Midiverb 4 to control output volume, and my Boss SE70 has its output level mapped to aftertouch, which allows me to draw in a short effect volume fade at the end.

Have you ever been faced with recreating a mix that you haven't worked on for weeks? Martin Walker explains how he manages to do just that, without the benefit of expensive automated mixers or a tape‑op with a notebook!

Unless you have a fully automated studio, or a mixer along the lines of the desirable Yamaha digital series, it can be difficult to work on more than one piece of music at a time, simply because most of us can't remember — and find it tedious to note down — every setting of every control, when moving from one project to another. Ideally, there would be a way to remove some of the variables and automate some of the others, and all without spending any more money. Read on...

The 'Before' Scenario

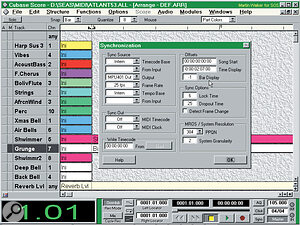

Putting an extra bar before the music data starts allows you to enter extra MIDI data so that each track is properly initialised. In Cubase, the Synchronisation options allow you to enter an offset for the Time and Bar displays, so you can still start your music at bar one, beat one as before, and with the time correctly shown starting at 00:00:00:00. Notice the extra track for setting up effect units.

Putting an extra bar before the music data starts allows you to enter extra MIDI data so that each track is properly initialised. In Cubase, the Synchronisation options allow you to enter an offset for the Time and Bar displays, so you can still start your music at bar one, beat one as before, and with the time correctly shown starting at 00:00:00:00. Notice the extra track for setting up effect units.

If you're working on an album's worth of music, it can often be tricky moving between individual tracks. Recreating the same mixer levels, EQ, and the settings of every effects unit, as well as making sure you have all the same sounds available in your synths, can become a nightmare. Consequently, many people tend to work on a single track until it's finished, and then mix it down before moving on to the next one. This sometimes results in a selection of tracks that don't sit together as well in context, since the last mix may occur several months after the first. If you take on commercial projects, as well as working on your own music, once again you may be faced with the prospect of losing all your current settings suddenly, when a customer wants a quick remix of a track that you thought was finished a week ago.

If you have a huge outboard rack, a mixer that crosses several timezones, and a patchbay that would make BT green with envy, you'll probably be able to afford full automation anyway, but if you're not in that fortunate position, there are still many things you can do to make your life easier, as well as providing some simple automation if your setup is mainly MIDI based. These techniques are not new; neither are they revolutionary, and a bit of effort will be required to set everything up. But once this is done, it should be possible (depending on how you work) to move between tracks in a small project studio (of, say, up to 24 mixer channels and half a dozen synths) in under five minutes, and achieve a high level of 'repeatability'.

Sounds Easy

Here's one way to format the required mixer settings, when adding them to your MIDI sequence. The size of the Cubase Notepad window used in this example is fixed (although it can be scrolled vertically), which restricts your options, but obviously, the less information you need to type for each sequence the better. One useful hint is to use the normal text Copy and Paste facilities to quickly move a empty 'dummy' layout between sequences, to save having to type in the whole thing each time.

Here's one way to format the required mixer settings, when adding them to your MIDI sequence. The size of the Cubase Notepad window used in this example is fixed (although it can be scrolled vertically), which restricts your options, but obviously, the less information you need to type for each sequence the better. One useful hint is to use the normal text Copy and Paste facilities to quickly move a empty 'dummy' layout between sequences, to save having to type in the whole thing each time.

The MIDI side of this is simplicity itself, and I'm sure everyone will already know the basic approach. For each of your synths and effect units, you need to ensure that the required sound data for a particular track is exactly as it was the last time you ran the sequence. If you leave a favourite bank of sounds permanently installed in a particular device, you simply have to insert the appropriate MIDI program change message (and Bank Select, if required) at the start of your sequence data. At the very least, this saves you from having to remember which sound you used last time you worked on the track. If you have a vast collection of sounds, and a computer librarian/editor, you can either set up a system as I described in 'Patch Work' (see the November 1997 issue of SOS), to download the data associated with each track, or make a text note somewhere within the sequence to remind you which sounds in which bank you used.

If, like me, you rarely use a standard bank of sounds, but load in a new batch for each track, it's also a good insurance policy to name each track of your song with the actual program or sample name in full (most sequencers allow a sensible track title length to be entered). This may seem tedious, but could prove invaluable. After managing to corrupt a 270Mb Syquest cartridge full of Akai samples, I had to reformat the cartridge, and recreate its contents from backups on several hundred floppy disks, but because each track of the album I was working on had the exact name of the sample used, I managed to match the sounds exactly. If I'd simply had track names like 'Guitar' or 'Strings', I'd never have managed to do this. See the 'File Facts' box for other ways to make your life easier with names.

Problem Sources

A mockup Master Document, showing the sort of data you need to note down.

A mockup Master Document, showing the sort of data you need to note down.

Once you have a sensible system to keep your sounds under control, the main obstacle to a repeatable mix is recreating the settings of the mixer itself, along with any stray knobs on effects units, synths and so on, that may alter from time to time. This may seem totally impractical at first, until you start to think about it a little more. On your synths, the only front panel knob or slider not remembered by MIDI will probably be the master volume control, and this is best always left at maximum (for best noise performance), with the overall track levels controlled by a combination of mixer gain/fader settings, and MIDI volume and velocity values. To get off to a flying start, push your synth master volume knobs up to maximum, and you can normally forget all about the other physical synth controls, as their values will be recorded as part of the MIDI performance.

Although having the correct sounds and mixer settings is vital for recreating a mix, effects can also play a very important part in the proceedings. Fortunately, most of the information required can be incorporated into a sequencer track (providing your effects units have MIDI, as the vast majority of modern ones do), along with a few additional notes, and a little bit of initial setting up.

I've found the easiest way to do this is to create an extra sequencer track just for effect settings. Since changing any MIDI parameters on an effect unit can result in audio glitches if an audio signal is passing through at the time, I normally add an extra bar before the actual music starts (see screenshot below). This effect track contains initial MIDI program changes, and since the MIDI channel has been set to 'Any' you can include information in this one track for sending to several units, each on a different MIDI channel. I also use this extra track to add short SysEx commands, which initially set the output volume of each effect unit to zero. Many units allow volume to be mapped to something like a MIDI controller, for real‑time level manipulation. Initially setting output volume to zero normally makes the effect noise level plummet, and by adding a further command to increase it to maximum as soon as the music starts, you get a much cleaner start to the track, since in my experience it's the effects units that produce the most noise in many mixes. In the same way you can fade out or cut the effect volume at the end of the track too.

During track playback you'll probably find that effects patched in via aux sends or inserts always receive similar input levels, so once you find the best input level setting on your effects unit (occasional flashes of the clip LED is normally optimum), note it down in your Master Document (see 'Mastering the Settings' box), just in case the knob ever gets moved by accident. Most mixers are designed such that nominal aux levels are at around 7 or 8 on the mixer send knobs, and this still gives you the opportunity to whack it up to 10, if you need a bit more effect to make one sound stand out.

Mix And Match

Having dealt with sound sources and effects, we only have mixer settings to consider, and although there are a huge number of these, the only ones that concern us are those that are being used creatively. Those that are at '0' (either a nominal central setting in the case of EQ, or an 'off' setting for levels) don't need remembering; only those that have an intermediate value depending on the particular piece of music. If, like me, you try to select the most suitable sounds for the mix in the first place, rather than bullying the wrong sound into submission by EQing it savagely, you'll have even less to note down, as EQ settings will mostly be confined to a few gentle rolloffs, a bit of subsonic rumble removal, or some subtle shelving to improve the way everything sits in the mix. So, in reality, each mixer channel may only have a few controls whose settings need to be remembered, and you now approach a more manageable number of variables.

Instead of reaching for a notepad and biro at this point, I suggest you exploit your sequencer. Most modern sequencers have some sort of text input facility: Steinberg's Cubase has the Notepad shown in the example screenshots (see left and below), because this is what I most regularly use; Emagic's Logic Audio has Marker Text Windows, and Cakewalk has the Lyrics View. All you need is the facility to type in a small amount of text alongside each sequence, so that it is permanently attached to the music data. If your sequencer does not have any of these options, you can use a simple text editor, but of course you lose the advantage of storing your settings in the same file as the MIDI data.

With Knobs On

Individual mixer settings come in two types: those that can be easily restored, and those with a wide range that are more difficult to return to the previous setting, and thus need a different approach. The bulk of the controls have a clearly defined range, such as 0 to 10 for Aux Sends, and ‑15 to +15 for EQ levels. These are easy to restore: simply ignore any mix setting that is at '0', and note down a repeatable setting for the rest. For instance, aux sends can easily be noted down as 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5 and so on, right up to 10 — a total of 21 unique settings, each of which is easy to recreate. In your sequencer Notepad (or Lyrics View, or whatever) note down, for each channel, any settings that are not '0', from top to bottom on the channel strip. For instance, a typical entry might read Channel 1, HF +4, LF ‑3.5, Aux 6.5, 8, Pan R2. This means that the HF knob was set to +4dB, the mid control (not noted) was still at 0dB, LF was at ‑3.5dB, Aux 1 send was 6.5, Aux 2 Send at 8, and the Pan control was at '2' towards the right hand side. Once you have a simple text system like this embedded in your sequence, it is easy to run through each channel in turn, updating each control that is not at '0'. The only EQ controls with too wide a sweep to be easily repositioned are any providing mid‑frequency sweep, as these tend to have a much wider range, and it is difficult to accurately recreate exactly the same frequency setting. Even so, most mixers provide sensible marking around their rotary controls, and you should be able to home in fairly accurately in most cases.

The main problem with mix recreation is restoring levels accurately, as the balance between sounds is arguably far more important than slight changes in EQ setting. There are two mixer controls associated with channel level settings: the input gain control at the top of each channel strip, and the fader at the bottom of it. Coming up with a system for repeatable gain and fader settings takes rather more thought, and mine evolved from noticing the typical settings I was making during a mix, using a range of synth keyboards, samplers and rackmount modules. The channel fader is very easy to set to a particular value, since it has a fairly long throw (even on mini‑mixers with 60mm travel), and there are normally plenty of numerical markings: +10, +5, 0, ‑5, ‑10 and so on, so that you can return a fader to a setting of ‑6dB, for instance, with few problems. On the other hand, the input gain control has a typical total range of something like 40dB, and it would be extremely difficult to accurately reset this on the basis of the average markings found on mixer front panels. On mine, for instance, the gain control is marked '10', U (unity gain), 25, and then 54dB right at the top.

Lining Up

There is no substitute for lining up a mixer to set the gain structure correctly. Adjusting the input gain for each channel to get the optimum signal level passing through the circuitry means that noise and distortion figures are optimised, and performance will be as good as the mixer designer intended. The basics of gain structure have been mentioned many times before in these pages, but the beauty of using mainly MIDI sources is that noise is normally low enough to allow you to try out a slightly different technique.

The classic procedure is to use the PFL (Pre‑Fade Listen) button to monitor the input level to each channel in turn, and adjust its input gain so that the mixer meter is peaking at around 0dB VU. However, doing this for each song would obviously give different gain settings every time, depending on the sounds used, and it would be difficult to accurately recreate the same setting in the future. Since the level from a synth or sampler tends to be quite similar from song to song, I found myself leaving the gain at the same fairly optimum setting each time, and relying on MIDI data to set the relative levels of instruments. I also found myself leaving the majority of channel faders at 0dB. Neither of these compromises to the gain structure will affect noise levels significantly, as long as the signal levels are in the right ballpark and the synths have low noise levels anyway.

You can set the overall instrument levels using a combination of MIDI volume commands and MIDI velocity values, and create fades and swells with MIDI expression controllers. As long as you set up the input gain control correctly in the first place for each synth, you can leave it alone entirely, as well as the channel faders, reserving these for what they do best — fading at the ends of tracks. Unless you simply must grab handfuls of faders during a performance, to mix 'on the fly', transferring this function to MIDI performance data will give you a good deal of built‑in automation in your music, while simultaneously allowing much more repeatable mixes. The secret is in the setting of the input gain control.

Although leaving the gain control in the same position is the essence of this repeat performance technique, you have to come up with a way to set it up accurately in the first place, and this method must be repeatable, to cope both with changing synths, patchbay connections, and accidental movements of the controls. Imagine what would happen if any gain control was accidentally moved in a month's time — recreating any of your carefully tweaked mix levels would then be very hit and miss. The answer is to adapt the classic mixer line‑up procedure: but instead of using a built‑in 1kHz mixer oscillator as a source, you create a patch in each synth that mimics this — in effect, a built‑in line‑up oscillator for each of your regularly used MIDI devices. You can then simply select this patch, use the PFL button on the appropriate mixer channel, and accurately line up your mixer gain control to within a dB or less of the same setting every time. Even if the synth in question hasn't been plugged into the mixer for six months, it only takes a few seconds to accurately recreate exactly the same levels as before.

Sine Of The Times

Don't panic at the thought of programming your own sine wave line‑up patch for each and every synth. The beauty of this sound is that everything must be in its pure 'vanilla' state — no fancy envelopes or LFO settings to create. Many synths and samplers have a basic sine wave which can be pressed into service: if not, find the nearest pure sound. A piccolo is good, as is a flute, as long as the sound has no vibrato, which will make its output level wobble about. Any filters should have their frequency set wide open, and resonance to minimum. Set the output level to the maximum available, and use a basic organ‑like on‑off envelope to keep the level absolutely steady. Once you have a basic sine wave sound, you need to ensure that its output level stays constant. If you can, reduce velocity response to zero to ensure this, but if this is not possible, use a sequencer or MIDI utility program to generate the same MIDI velocity each time — a value of 127 (maximum) is probably most useful. A 1kHz frequency is normally used for lining up, and the closest note to this on a MIDI keyboard is B5 (MIDI note number 83, and nearly two octaves above middle C).

The actual lining‑up procedure will depend somewhat on how you use your MIDI sources. I tend to use anywhere between one and half a dozen sounds simultaneously on each of my synths (one on each MIDI channel), and have found that using a steady 1kHz 'flat out' sine wave patch needs the input gain control setting at something like +6dB VU on the mixer, and the input gain setting will probably be at something like unity (this will be 20dB if your line input has a 20dB pad — see your mixer manual). This should ensure that, when a more typical percussive sound is used, with lower mean levels, you get a healthy overall mix level emerging from the mixer's main outputs. The secret is to find a suitable setting for your synths, and then stick to it.

First, set up a typical mix using an existing song, but with the channel faders all set to 0dB.

- Adjust the mix using the input gain controls until it is about right, and then stop the sequence.

- Now, on each of your synths, play the sine wave patch at 1kHz, and using the channel PFL button, adjust the input gain control to achieve the nearest exact reading to one of the LEDs on the mixer output meter (see 'Getting up the Ladder' box). This should only take a few seconds.

- Note down in your Master Document the LED value used for the synth.

The Final Mix

You have now lined up your synth levels in a very repeatable way, and can fine‑tune them using your sequencer, either through MIDI volume commands, or simply by adding an offset to MIDI velocity values for the whole track. If you regularly use multiple outputs on a particular device, it's even easier. My Akai S2800i sampler has L and R stereo outputs, as well as two mono ones labelled 1 and 2. Akai have thoughtfully provided a line‑up oscillator on this instrument (found on the Tune/Level page). I simply switch this on, and for each of the four mixer channels used, line up the appropriate mixer channel accordingly. The oscillator only emerges on the L and R outputs, so it's necessary to temporarily plug either the L or R output into the mixer channel used by outputs 1 and 2, to set these two up as well. However, all four mixer channels can be set using this single supplied tone.

The only exceptions to this technique are stereo mixer channels, since these mostly employ a +10/‑4 gain switch, rather than a fully adjustable gain control. In this case, find the most appropriate setting for your synth (or effects unit), note it down in your Master Document, and then also make a note of the position of the channel fader for each track. I find that stereo mixer channels are often used for effects units, and in my experience these can be the noisiest devices in the mix. The further down the channel fader can be, the less noise these units will contribute to the mix. It's best to get as much level into the effect as possible (without distortion), and then pull down the channel fader to set output levels exactly.

You may be thinking that this all sounds a bit involved, but the majority of the work is in initially setting up the system, and this should only take a few hours. Many people leave most of their synths permanently connected to the same set of mixer channels, and if you're one of these once you have your sine wave 1kHz patches, and the Master Document, all the levels can be automated through MIDI, and the only things that change from mix to mix are the EQ, aux send and pan settings. Once you've tried it, and found that even mixes created last year still sound exactly the same, I'm sure you'll agree that it was worth the effort!

File Facts

It can save a lot of hassle if you stick to a consistent system for naming sequence and sound banks. Using a working sequence title (for instance Moody01.MID), with data banks containing the same name (Moody01.BNK, Moody01.SYX and so on) is a great help. I normally use filenames that end in a two‑digit number, so that every time I make a significant change to the track, I can increment this number by one when I save the new version. Using a two‑digit number at the end (03, for example), ensures that all of your 'takes' stay in chronological order in the 'Open File' dialogue. In the same way, whenever you change sounds in a synth, save them in line with the current song name, so you won't end up wondering which of the dozens of 'in progress' files was actually the one that goes with a particular take.

I always keep at least two previous versions of each set of files on my hard drive, as well as a daily backup to a different drive in case of accidents. So, for instance, if you're currently working on the track 'Ambient17.MID', your synth sounds will be 'Ambient17.BNK' (or whatever), and you still have 'Ambient15' and 'Ambient16' versions, while you wipe all 'Ambient14' files and before. This way, you get great insurance just in case any file gets corrupted, and you can also always find which sound banks went with which sequence data. Even if you find that you prefer the version you saved yesterday, you can simply revert to this version, along with its sound banks, without having to remember whether you changed any of the sounds in the meantime — the patches and other settings will stay 'in sync'.

Mastering The Settings

Although the techniques I've described are designed to minimise the amount of data you need to write down, it is very important to create one 'Master Document' using a word processor. In this, note the level settings you decide on for lining up each of your synths and samplers, and any settings of their controls that may get changed, either deliberately or accidentally. There is nothing more frustrating than finding that, despite setting up the mixer controls perfectly, something still doesn't sound right — it might be, for instance, because of a +10/‑4 switch setting on an effect unit back panel, or the position of a rotary control on the front panel.

The beauty of the system described in the main text is that once you get a good working set of levels, even the levels sent to your effect units will be much more consistent, so that you can normally leave the knobs alone. The importance of keeping a Master Document is that once you become used to working in this way, if someone comes along, twirls a control and says 'What's this do?', you can relax in the knowledge that you can look up exactly the way you set this control up, and can thus return it to its correct system position.

Getting Up The Ladder

Nearly all modern mixers have LED ladder arrays for level display, and between each 'segment' there is normally a gap of three or four dBs of level. There is a technique for setting levels that allows you to get much more accurate settings for line‑up purposes. The secret is to rely on the transition point between each segment. For instance, to achieve an accurate +6dB VU setting, edge up your channel gain control from a lower level, until the +6 LED segment is just lit — if you want to be finicky, you can even manage to get it to be dimly lit, just on the verge of full brightness. This should allow you to achieve gain settings certainly within a dB or less of the previous value every time. Incidentally, the centre detent on pan and EQ rotary controls may typically be +/‑ 0.5dB of the actual central value, due simply to the manufacturing tolerances of the control itself, so our repeat settings are about as close as you will get.