Your toolkit for producing polished, contemporary‑sounding vocals should include appropriate EQ techniques and subtle ambience processing. Enter the workshop...

Last month, we looked at various options for fine‑tuning a vocal recording, covering basic pitch correction, vocoding techniques for applying varying levels of disguise to the natural imperfections of the human voice, and dynamics control without using compressors. This month I'll extend the discussion of vocal manipulation into the areas of equalisation and ambience control.

Equalisation

I'll be using Logic Pro's Channel EQ for all examples in this section, not because it's simple to use (actually, it's one of the most complex EQs available in Logic) but because it has a visual display of choices made that really helps you understand what's going on. It also has an Analyser mode that shows the real‑time effect of your actions on the waveform being processed (when the mode is set to 'post EQ').

The application of a high‑pass filter set at 50Hz. Although the filter has been applied, the Analyser is set to pre‑EQ and you can clearly see the low‑end information that needs to be removed. Note also the settings for the Analyser.

The application of a high‑pass filter set at 50Hz. Although the filter has been applied, the Analyser is set to pre‑EQ and you can clearly see the low‑end information that needs to be removed. Note also the settings for the Analyser. The application of a high‑pass filter set at 50Hz. Here the Analyser is set to post EQ. Note the removal of most of the unwanted low frequencies, although some still remain at or around the filter cutoff point. In this case, a slightly higher cutoff frequency may be justified, but use your ears, not your eyes, to make the final decision!Most vocal recordings benefit from the application of a high‑pass filter (see top two screens, right). A typical project studio recording contains all sorts of low‑frequency information (including traffic rumble and foot tapping) that, although you cannot hear it (unless you have monitors with an even frequency response below 50Hz), will be sucking energy from the mix, and giving your power amp a harder time into the bargain. So a simple high‑pass filter set at approximately 50Hz will usually have no significant impact on the quality of the sound you do want to hear, and will guard against any potential problems that low‑frequency material can cause.

The application of a high‑pass filter set at 50Hz. Here the Analyser is set to post EQ. Note the removal of most of the unwanted low frequencies, although some still remain at or around the filter cutoff point. In this case, a slightly higher cutoff frequency may be justified, but use your ears, not your eyes, to make the final decision!Most vocal recordings benefit from the application of a high‑pass filter (see top two screens, right). A typical project studio recording contains all sorts of low‑frequency information (including traffic rumble and foot tapping) that, although you cannot hear it (unless you have monitors with an even frequency response below 50Hz), will be sucking energy from the mix, and giving your power amp a harder time into the bargain. So a simple high‑pass filter set at approximately 50Hz will usually have no significant impact on the quality of the sound you do want to hear, and will guard against any potential problems that low‑frequency material can cause.

Continuing with the theme of removing unwanted sound, the technique sometimes called 'remedial EQ' — that is, the location and removal of unwanted frequencies — is easy to apply with Channel EQ.

1. Begin by selecting one of the four 'peaking' EQ bands available and turning up its gain. You'll have to take a little care with this, as the gain will need to be set fairly high for the technique to work. (Be aware that when you find the offending frequency, the resulting jump in volume caused by a combination of the amplitude of the original sound and the gain of the EQ band means that the sound could be surprisingly loud. Don't overdo the gain setting until you are well practised and comfortable with the technique.)

The first stage of the 'search and destroy' remedial EQ technique involves turning on a peaking EQ band, turning up its gain, increasing the Q to maximum, and searching for rogue resonances by 'sweeping' the frequency.

The first stage of the 'search and destroy' remedial EQ technique involves turning on a peaking EQ band, turning up its gain, increasing the Q to maximum, and searching for rogue resonances by 'sweeping' the frequency.

2. Next, turn up the Q control for the chosen band, to narrow the band of frequencies selected, then sweep the centre frequency of the band slowly left and right, searching for rogue resonances. These can be caused by several factors, including a 'chesty' or nasal vocalist, or a room that has not been perfectly treated for standing waves. When you find an imperfection, it will be obvious, as the amplitude of the unwanted frequencies will combine with the gain of the EQ and it will 'jump' out of the mix.

Having found the 'rogue' frequencies, reverse the gain to remove them.

Having found the 'rogue' frequencies, reverse the gain to remove them.

3. The final step is to reverse the gain of the EQ band to filter out the offending frequency. This technique can be very useful for removing undesirable coloration, but be careful: if it's over‑used you can end up removing all the character and body from a vocal recording. To 'make room' for the vocal, it is often recommended to lower the gain of frequencies between approximately 100Hz and 500Hz in other tracks, especially guitars, but the vocal track will not be able to make best use of the space provided by doing this if it has had its own lower‑mid surgically removed!

Edge & Air

An example of EQ applied to enhance consonants. The higher end of this band will heighten the perception of 'air' in the vocal. The gain is set deliberately high here to better illustrate the effect. Again, your ears must be the final judge.

An example of EQ applied to enhance consonants. The higher end of this band will heighten the perception of 'air' in the vocal. The gain is set deliberately high here to better illustrate the effect. Again, your ears must be the final judge.

Another common EQ technique for enhancing vocal tracks is to slightly accentuate the detail, or higher frequencies, in a vocal recording, increasing the impact of consonants (the 'edges' of the words or syllables) and brightening the overall sound. A slight boost (between one and three decibels) of a broad range (low Q) of frequencies, probably around 2‑5 kHz, is all that is required to achieve this effect. Slightly boosting a higher range of frequencies (say, 5‑10 kHz) will bring a lightness or crisp quality to the vocal. This is sometimes referred to as 'air', as it will emphasise any breath‑related non‑verbal aspects of the recording.

Using bus sends to pass some of the channel signal to an auxiliary channel, on which is inserted your reverb of choice, reflects standard hardware‑based practice. A refinement of this treatment that works well on vocal tracks is, in addition to using the send method, to insert a reverb on the channel itself, for the purpose of adding 'body' to the sound. This instance of reverb is not for making the voice sound as though it's in a performance space (perhaps along with other performers), but for augmenting the perceived quality of the sound itself. Space Designer has a preset designed with this in mind, called 'Thicken Vocals', but any setting whose decay time is less than about 0.5 seconds can be used, with careful control of the effect level. For example, in Space Designer, the amount of 'thickening' can be controlled by adjusting the Rev slider (that is, the 'wet' level).

Avoid The 'Wall Of Mud'

Mike Senior talks in more general terms about this (and other reverb‑based techniques) in his 'Use Reverb Like a Pro' articles (see /sos/jul08/articles/reverb1.htm and /sos/aug08/articles/reverbpart2_0808.htm), and warns against the 'Wall of Mud' that can be created by over‑use of reverb. Many modern mixes appear to have dry or untreated vocals, but if you simply leave your vocal tracks with no treatment whatsoever, they will sound sadly flat and 'unmixed', just as you recorded them. What we need here is to somehow add a little magic, to make the vocal sound 'treated' without the effects being obvious. Logic Pro has several plug‑ins we can use to achieve this.

Spreader

The traditional way of creating a 'doubled' vocal sound is to simply re‑record it. Panning one channel away from the other then gives an impression of width. The Spreader plug‑in works by applying very short delay times with modulation of the frequency range, and recombining this with the original signal, producing doubling and width‑enhancement tricks similar in some respects to the automatic double‑tracking units of yesteryear. To apply this effect to a mono source, you have two options. The first is to create a send to a stereo auxiliary channel. Using this method you are mixing 'spread' sound with the original mono source:

1. Click and hold on the channel send selector and choose an unused bus. If your channel is mono (which is likely, as it is a vocal channel) the send will be mono, and a mono aux channel is created, as long as that bus has not been used before (see 'Buses & Auxes' box).

2. Convert the aux channel to stereo by clicking the mono/stereo button. This avoids what appears to be a bug in Logic's Mixer, where you can choose the 'mono > stereo' instance of the Spreader plug‑in, which converts the aux channel to stereo, but the mono/stereo button continues to indicate a mono channel.

3. Insert the Spreader plug‑in on the aux channel.

The second option is to route the vocal channel to a stereo auxiliary channel. This method replaces the mono source with the 'spread' version:

1. Route the vocal channel to an unused bus by click‑holding on the output selector.

2. Insert the Spreader plug‑in on the aux channel. Note that when you route a mono channel to an unused bus, the bus and its auxiliary channel are stereo by default.

The New Track with Duplicate Settings button (and the handy help tag confirming that!).

The New Track with Duplicate Settings button (and the handy help tag confirming that!). Doubling a vocal with Spreader. Spreader is set up on an auxiliary effects return channel, to which the main vocal channel is assigned to send.

Doubling a vocal with Spreader. Spreader is set up on an auxiliary effects return channel, to which the main vocal channel is assigned to send. You can retain extra flexibility by duplicating the vocal channel and routing it to an auxiliary effects return channel, with Spreader inserted on that channel.

You can retain extra flexibility by duplicating the vocal channel and routing it to an auxiliary effects return channel, with Spreader inserted on that channel.

Option 1 has the advantage of retaining the original mono signal in its own channel (and is more likely to work when the whole mix is played back in mono — see 'Mono Bounces' box), but the 'spread' effect is less obvious. To retain the choice, create a duplicate of the mono vocal channel (by clicking the 'New Track with Duplicate Setting' button), and then option-drag the region(s) required to that track. Set up the two vocal tracks as option 1 and 2. Alternating with the non‑spread version (say, from chorus to verse) can be achieved by automating the send control, or the Mute button of the effects return channel, or by having another duplicate of the vocal track, which is not passed to the Spreader. The arrangement of which part gets 'spread', and how, can also be taken care of with region mutes (use the Mute tool, or select a region and press 'M' on your keyboard).

- Ensemble

A single Chorus or Flanger will bring a sense of movement to a sound, but the Ensemble plug‑in is often more effective. It combines up to eight chorused voices, creating a far more complex effect, which can therefore be applied with more subtlety. Similar to using Space Designer reverb to add body, Ensemble can add that 'something' if used sparingly, without being obvious as an added effect.

- Delay

As with reverb, small amounts of delay can alter our perception of the sound itself, as opposed to creating an awareness of the effect for its own sake. Delay has an advantage over reverb in that it's a small number of distinct repeats, which is good news in terms of clarity.

Typical settings for the Stereo Delay plug‑in when used to add subtle 'life' to a vocal sound, without being obvious as an effect.The Stereo Delay plug‑in is perfect for this task, and can be used in two ways. When inserted directly on the channel (usually mono for a vocal track) the two outputs of the plug‑in are fed back into the mono signal, and the repeats 'combine' more successfully with the dry signal. When inserted on a stereo aux channel, the repeats are heard hard left and right, away from the position of the original source channel. Typical settings for the plug‑in would be zero feedback (so only one repeat), short delay (80‑200 ms, and a different setting for each side) and very low 'wet' levels (if inserted) or send levels (if used in an aux channel).

Typical settings for the Stereo Delay plug‑in when used to add subtle 'life' to a vocal sound, without being obvious as an effect.The Stereo Delay plug‑in is perfect for this task, and can be used in two ways. When inserted directly on the channel (usually mono for a vocal track) the two outputs of the plug‑in are fed back into the mono signal, and the repeats 'combine' more successfully with the dry signal. When inserted on a stereo aux channel, the repeats are heard hard left and right, away from the position of the original source channel. Typical settings for the plug‑in would be zero feedback (so only one repeat), short delay (80‑200 ms, and a different setting for each side) and very low 'wet' levels (if inserted) or send levels (if used in an aux channel).

Creating A Reverse Reverb Effect

Originally created by swapping spools on a reel‑to‑reel tape recorder, recording reverb onto the tape as it ran backwards, and then flipping the spools once more, reverse reverb's digital equivalent involves a fairly similar process:

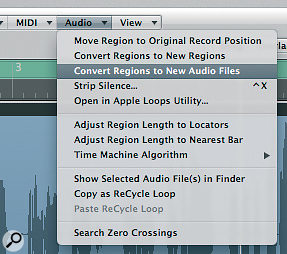

Use 'Convert Regions to New Audio Files' — found in the local Audio menu of the Arrange area — to duplicate your original vocal audio file before carrying out the destructive edits needed to create reverse reverb.

Use 'Convert Regions to New Audio Files' — found in the local Audio menu of the Arrange area — to duplicate your original vocal audio file before carrying out the destructive edits needed to create reverse reverb.- To ensure you're not working on the original audio file (as you're about to carry out several destructive edits), select the region to which you'd like to add reverse reverb, then choose 'Convert Regions to New Audio Files' from the local Audio menu in the Arrange area. This option creates a new audio file, and also replaces the region with the new whole file region.

- To open the region in the Sample editor, double click it on the Arrange area. Or, to open it in a new Sample editor window, select it in the Bin and choose 'Sample Editor' from the Window menu.

- Choose 'Reverse' from the local Functions menu (in the Sample editor).

- Add a reverb plug‑in as an insert and choose an appropriate setting. You'll have to experiment here, as there is a fair amount of guesswork involved when it comes to predicting what the sound will be like when reversed. My advice would be not to choose anything with a long decay, but it will depend on the material and the tempo of the song.

- Bounce the track, having soloed it. You will need to define the start and end of the bounce carefully in the Bounce window. Selecting the region in the Arrange area and clicking 'Set Locators' on the Toolbar (see screen below), before opening the Bounce dialogue, is a quicker way to achieve this.

- You will also need to decide whether or not you want to 'flatten' the plug‑ins into the bounced file. If you choose the latter, and you wish to re‑import the bounced file to a track with the plug‑ins still active, bypass the plug‑ins (except reverb!) before you bounce.

- Drag the bounced file out of the Bin back onto the Arrange area — either to replace the un‑bounced version or onto a new track (created with identical settings by clicking the 'Add New Track with Duplicate Settings' button).

- Open the newly bounced region in the Sample editor.

- Choose 'Reverse' from the local Functions menu (in the Sample editor).

Maybe it's time to start using tape again…

Mono Bounces

By default, bounces of Logic projects create stereo files. That is because a bounced file is essentially the output of the 'Output 1‑2' channel — a stereo channel. To bounce in mono, go to the Output 1‑2 channel and change it to a mono channel by clicking the Mono‑Stereo selector switch, then bounce as normal. There are a couple of reasons why you might want to do this: firstly, you might be bouncing a mono track or tracks, for further use in the project (see the 'Reverse Reverb' box for an example). Secondly, you may want to check what will happen to the stereo information in your mix when it is played through a mono system (such as a kitchen radio).

Buses & Auxes

Take care with buses and aux channels: only if you select buses in order (without creating aux channels as a separate task by clicking the 'Create Aux channel' button in the Mixer window) will the sequential link between them be maintained. When this sequence is lost, things can get confusing. Naming aux channels (by double‑clicking the channel name in the Mixer) is highly recommended!

Using The Channel EQ Graphic Display

Dragging numbers up and down to alter parameters is fiddly work, and often you need to reset to default values and start again. This is easily achieved by Option‑clicking on any parameter you wish to reset. Resetting the whole plug‑in is achieved by choosing 'Reset Setting' from the plug‑in's preset menu.

Many users prefer to deal with the graphic interface rather than the number fields, so here are some tips that may help avoid frustration:

- To change the gain, place the mouse pointer near the EQ band you want to change — a small node appears indicating that the band is active — and drag up or down.

- To change the Q, place the mouse pointer on the node and drag up or down — bizarrely, the Q value goes down as you drag up!

- To change the frequency, either of the above mouse positions will work. You simply drag left or right.