Have you ever wondered why Power PC plug-ins can't run in Intel applications, or why your 32-bit plug-ins won't work in 64-bit applications of the future? Apple Notes explains all.

While the Mac enjoys a well-deserved reputation for its ease of use, and a place in the hearts of a large number of musicians and audio engineers, Mac users have had to put up with a fair number of complicated architectural transitions over the past few years. It started with the introduction of Mac OS X in 2001, continued with the change to Intel processors in 2006, and will now happen again as we migrate to applications that can take advantage of 64-bit memory addressing.

Each of these architectural shifts has meant that new versions of the applications people rely on every day have to be created. And because so many musicians and audio engineers became more reliant on plug-in software effects and instruments in the '90s (was it really so long ago?), each shift has also meant an even bigger headache in getting all of your favourite plug-ins to work again.

I don't know what the exact ratio of applications to plug-ins is, but it probably wouldn't be far-fetched to say that for every major application that needs to be ported there are probably several hundred plug-ins as well. And because there are so many, and so much diversity in the ecosystem that develops them — from students to seasoned pros — it's inevitable that some plug-ins never get ported to a new architecture, which is frustrating if you rely on such tools but you still need the latest Mac hardware or software.

Part Of The Process

In order to understand why it becomes impossible to run certain plug-ins with certain application software and hardware combinations, we need to take a brief look under the bonnet.

When you run an application like Logic Pro, Mac OS X creates what's known as a Process, which, simply put, is responsible for running the application in the OS. This is somewhat analogous to a recipe requiring a chef to cook it, where an application's code can be thought of as the recipe and the chef is the Process. If one chef gives his undivided attention to a single recipe, you'd need another chef to cook a second recipe, and similarly each application you run in OS X requires a new, independent Process. You can see how many Processes Mac OS X is running in the Activity Monitor, found under Utilities in the Applications folder.

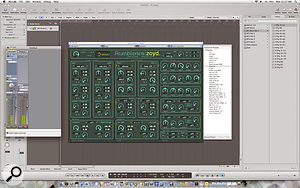

Core MIDI can be used to send events from an Intel-based application (such as Logic Pro) to a Power PC application (here, AU Lab, running via Rosetta) over an IAC bus.However, when you use an Audio Unit in Logic Pro, instead of a new Process being created to run that plug-in, the Process that's running Logic Pro also becomes responsible for the plug-in, which is why you won't see plug-ins listed in the Activity Monitor. (Although my example refers to Logic Pro and Audio Units, the principle is the same for any host that runs a plug-in.)

Core MIDI can be used to send events from an Intel-based application (such as Logic Pro) to a Power PC application (here, AU Lab, running via Rosetta) over an IAC bus.However, when you use an Audio Unit in Logic Pro, instead of a new Process being created to run that plug-in, the Process that's running Logic Pro also becomes responsible for the plug-in, which is why you won't see plug-ins listed in the Activity Monitor. (Although my example refers to Logic Pro and Audio Units, the principle is the same for any host that runs a plug-in.)

Once you understand that an application and any plug-ins running within that application are part of the same Process, it's easier to understand issues like why you can't run Power PC plug-ins in an Intel application. Because a Process can only run the code for a single architecture, the Process has to be either running Power PC code (translated via the Rosetta translation technology on an Intel Mac) or Intel code. It also means that a Process has to run either 32-bit code or 64-bit code. So a single Process can't run Power PC and Intel code simultaneously, nor can it run 32- and 64-bit code simultaneously.

This ultimately means that because an application and its plug-ins run under the umbrella of a single Process, everything needs to support a single architecture, whether it's Power PC, Intel, 32-bit or 64-bit. And this is why Power PC plug-ins needed to be recompiled for the Intel (or Universal, supporting both Power PC and Intel) platform to be used in Intel-native hosts, and why 32-bit plug-ins will need to be recompiled as 64-bit plug-ins, to run in a 64-bit host application.

As an aside, the fact that an application and any plug-ins that are running in that application share a single Process also explains why 32-bit applications run into memory issues even if your Mac has a large amount of memory. Basically, a 32-bit Process in Mac OS X (running a 32-bit application) can only access 3GB of memory, and again, because the plug-ins running in an application share the same Process, they can only make use of that one 3GB pool of memory.

A 64-bit Process (created when a 64-bit application is run), on the other hand, can access more than 3GB of memory, which is why a 64-bit application running with 64-bit plug-ins will be able to make use of all the memory you have available, even though there will still only be a single Process running everything.

Inter-process Communication

Now we've discussed some of the technical details, you might be wondering why you couldn't just run two Processes at the same time, to eliminate compatibility issues. Why not have one Process running Intel code and another running Power PC code, and have the two communicate with each other? Well, not only is this possible, it's how two current products deal with the problem of running incompatible plug-ins on a modern system.

The first such solution is VST Bridge, supplied with the latest 4.1 versions of Cubase and Nuendo (and discussed in the Nuendo 4 review, SOS December 2007), which allows you to use Power PC plug-ins inside the Universal version of Nuendo running on Intel Macs. Presumably, it will also do the same for 32-bit plug-ins in the 64-bit versions of Cubase and Nuendo (as it already does on Windows), when they're available.

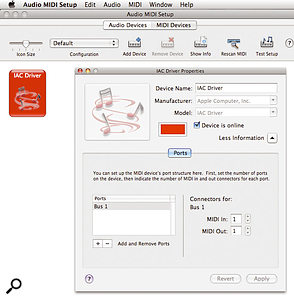

Using Audio MIDI Setup, you can enable the IAC Driver for sending MIDI data between two different Processes.The second solution is the Intel Wrapper recently introduced by Spectrasonics to allow the Power PC-only Atmosphere and Trilogy instruments to run on Intel Macs. This isn't to be confused with the type of wrapper that would allow you to run VST plug-ins in an RTAS host (such as FXpansion's VST to RTAS Adapter), since these are typically plug-ins that host other plug-ins, meaning that the RTAS host, the wrapper plug-in and the VST plug-in still all run within a single Process. With Spectrasonic's Intel Wrapper, you run a special Intel-compatible plug-in in your host (under the Intel Process), and that plug-in communicates with a separate Power PC Process running the actual instance of Atmosphere or Trilogy.

Using Audio MIDI Setup, you can enable the IAC Driver for sending MIDI data between two different Processes.The second solution is the Intel Wrapper recently introduced by Spectrasonics to allow the Power PC-only Atmosphere and Trilogy instruments to run on Intel Macs. This isn't to be confused with the type of wrapper that would allow you to run VST plug-ins in an RTAS host (such as FXpansion's VST to RTAS Adapter), since these are typically plug-ins that host other plug-ins, meaning that the RTAS host, the wrapper plug-in and the VST plug-in still all run within a single Process. With Spectrasonic's Intel Wrapper, you run a special Intel-compatible plug-in in your host (under the Intel Process), and that plug-in communicates with a separate Power PC Process running the actual instance of Atmosphere or Trilogy.

If you don't use Cubase or Nuendo and have some old Power PC instrument plug-ins you'd like to still use, there is a workaround. If you have a Power PC host, you can still run this on your Intel Mac to access Power PC plug-ins, and if you don't have such a host you can instruct a Universal application to run as Power PC code under Rosetta, by enabling the 'Open using Rosetta' option in the Info window for that application, which you can access by selecting Get Info on the application's icon.

Because Rosetta applications also have access to Core MIDI and Core Audio, you can run the Power PC host alongside your main music or audio application and send MIDI to it via Core MIDI's built-in IAC (Inter Application Communication) Driver. This is disabled by default, but you can enable it by double-clicking the IAC Driver in the MIDI Devices page of Audio MIDI Setup and enabling the 'Device is Online' tick-box in the Properties window. Initially you will have one MIDI bus available, providing both an input and an output, but you can create as many buses as required by clicking the Add Port button.

In your sequencer you can select the IAC bus as the output to a MIDI track, and in the Power PC host you can select the same IAC bus as an input to the Audio Unit instrument plug-in you want to play. For audio, you could use one of the many plug-ins that send and receive audio over a network to communicate between the two applications on the same Mac, such as Apple's AUNetSend and AUNetReceive pair, but in practice I found the latency less than ideal, compared with routing the Power PC host directly to a Core Audio device.

You might notice that since Leopard now supports 64-bit applications, with user interfaces for applications that include both 32- and 64-bit code, there's a new option in the Info window for applications: Open in 32-bit Mode. This forces an application to run as a 32-bit Process and will allow similar compatibility workarounds to those we've described for running a Power PC host. However, unlike Power PC Processes, which take a performance hit because they have to run translated Power PC code via Rosetta, there's no such penalty for running 32-bit code in a 32-bit Process alongside a 64-bit Process.

Ready For Review, It's Ten-Five-Two

It's not often that you can get excited about a minor 'point-one' upgrade to Mac OS X, but in the case of Mac OS 10.5.2 I'm prepared to make an exception. While such minor versions usually bring fixes, under-the-bonnet improvements, and the occasional incompatibility, 10.5.2 adds a couple of 'new' features to the user interface that address much of the criticism Leopard has received from existing Mac users.

When we discussed Leopard in January's Apple Notes (www.soundonsound.com/sos/jan08/articles/applenotes_0108.htm), two aspects of its user interface that didn't seem like a step forward were the translucent menu bar and the Stacks feature in the Dock. In the case of the menu bar, the new translucency meant you could see part of your desktop background underneath, enabling the menu bar to blend more seamlessly with the Desktop. In practice, though, this often made parts of the menu bar illegible, and looked ridiculous when running an application with a single window that takes up the whole screen, like Logic Pro or Pro Tools.

In 10.5.2 Apple have introduced a new option to let you disable the 'Translucent Menu Bar' in the Desktop part of the Desktop and Screen Saver System Preference, which is a big relief. And the menus themselves now also appear slightly less translucent than before, making them easier to read when there's lots of clutter on your screen.

Like many Mac users, I used to rely heavily on Tiger's ability to let you right-click on folders in the Dock to navigate the contents of those folders via pop-up menus, and, like many Mac users, was dismayed to find this behaviour replaced in Leopard with the useless Stacks feature. However, in 10.5.2 Apple have added a new List view to Stacks, which basically works just like the old Tiger behaviour, except that you now have to use a primary (left) click to open the pop-up menu, rather than a secondary (right) click, which I think I can live with!

Right-clicking a Stack, as in earlier versions of Leopard, lets you configure the Stack's behaviour, such as making it display as a List instead of a Fan or Grid, and 10.5.2 also lets you choose whether the Stack should show the icon for the folder placed in the Dock instead of the icon for one of the files within the folder. So finally, as with Tiger, my Applications folder now looks like my Applications folder again when placed in the Dock. Phew!

In other Leopard-related news, Digidesign have released a new 7.4.1 version of Pro Tools HD that's compatible with the latest Mac Pros featuring 5400-series ('Harpertown') Xeon processors running Mac OS 10.5.1; 10.5.2 is, alas, not supported at the time of writing. Still, this minor upgrade is important for Pro Tools users who purchased a new Mac Pro but couldn't officially run Pro Tools, since there was no way to downgrade the version of Mac OS X that came with the system to one that was approved by Digidesign.

Pro Tools HD 7.4.1 is not for users with earlier Mac Pros, however, so, like Pro Tools LE users, you'll need to wait for another phase in Digidesign's Leopard compatibility plan before you take the plunge with the latest version of Mac OS X.