These days, a new synth without some form of DSP effects processing is almost unthinkable — but it wasn't always like that. Paul Wiffen traces the introduction of effects on synthesizers and looks at making the most of the early implementations.

Back in the mists of prehistory, when dinosaurs still roamed the earth and this writer first encountered a synthesizer, the idea of built‑in synth effects was unthinkable. The fact that the synth had a knob or switch for every parameter of the oscillators, filter and envelopes made quite enough to deal with, without any further complication. Moreover, effects processors back then were not as plentiful as they are now. There were the really expensive reverb units, found only in recording studios, which had the first implementations of digital signal processing, and then there were cheap little pedals used only by guitarists to add wah, fuzz, chorus and delay — and no self‑respecting keyboard player would ever be seen using those (except Stevie Wonder with his auto‑wah on 'Higher Ground', of course). In those days, too, each of the effects you'd commonly find grouped together in the cheapest of today's digital multi‑effects units required a totally different bit of analogue circuitry to produce it.

The first synthesizer I ever saw with any kind of built‑in effects was at the first Frankfurt Musikmesse I attended, (at the start of the '80s), and from a most unexpected source. It was the Elka Synthex, and I actually got to meet the designer, Mario Maggi. At the time when the polyphonic synth market was dominated by Californians (Sequential Circuits and Oberheim), that a polysynth from Italy could out‑perform both the Prophet 5 and the OB‑series was quite astounding. Listening to the very preliminary presets they had thrown together for the Musikmesse, I was amazed at how full and rich this machine sounded. Let loose on it myself (Elka‑Orla UK were looking for someone to help demo it in Britain), I soon tracked down the source of this fullness. On the far right was an innocuous little section marked Chorus, with just three preset settings. Switching this off (it was enabled on most of the synth's patches) had the effect of reducing the sound to the level of other contemporary synths.

Elka Synthex: On the far right is an innocuous little section marked Chorus, with just three preset settings.

Elka Synthex: On the far right is an innocuous little section marked Chorus, with just three preset settings.

Chorus As Cholesterol

Back in those days there existed a phenomenon (which has long since died out) called the string synthesizer. The imitation of a string section was pretty much all these machines did — although occasionally there was a rather poor brass or electric piano sound as well — but they did strings much better than the polysynths of the day. There was the Solina String Ensemble, the Crumar Stringman... and, of course, Elka had their own string synthesizer, called the Rhapsody. This is immortalised in pictures of Tangerine Dream from the period, where the Elka is the only identifiable keyboard amongst walls of modular synths. The Synthex was the first truly programmable polysynth I had ever come across that could produce a thick ensemble string sound to match these dedicated string synths.

Of course, now I realise it was because all these string synths had hidden chorus circuits built into their hardware. Lord only knows how thin and nasty they would have sounded without them! The simple fact that the Synthex had a similar chorus circuit meant that it could make the same sort of washy string sound. In fact, it could produce a much wider variety of string sounds than the string synths, because you also had access to the thinner traditional polysynth pad if the chorus section was not used.

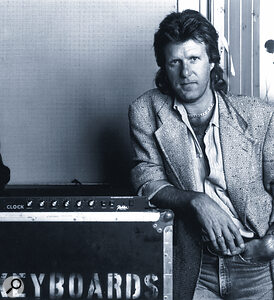

Keith Emerson.In action, the Synthex sounded massive. Being sent around by Elka to demo it for any keyboard players I could find, I personally witnessed the reaction of Keith Emerson, Geoff Downes, Jean‑Michel Jarre and Stevie Wonder. Now those of you who are old enough (cut your leg off and if you can count 40 rings, you're old enough) will remember that none of these gentlemen was exactly short of synths. Keith had around 20 in 1983, Geoff 47 on tour with Asia, and Jean‑Michel over 50. No‑one can count the number that Stevie has because, like painting the Forth Bridge, when you've finished you've got to start over again because he's bought half a dozen more!

Keith Emerson.In action, the Synthex sounded massive. Being sent around by Elka to demo it for any keyboard players I could find, I personally witnessed the reaction of Keith Emerson, Geoff Downes, Jean‑Michel Jarre and Stevie Wonder. Now those of you who are old enough (cut your leg off and if you can count 40 rings, you're old enough) will remember that none of these gentlemen was exactly short of synths. Keith had around 20 in 1983, Geoff 47 on tour with Asia, and Jean‑Michel over 50. No‑one can count the number that Stevie has because, like painting the Forth Bridge, when you've finished you've got to start over again because he's bought half a dozen more!

Despite the number of machines these guys had, they fell for the Synthex straight away. When his Yamaha GX1 couldn't travel any more, Keith used the Synthex to do the 'Fanfare'. Geoff Downes had me MIDI the Synthex to every keyboard he used on Asia's Aqua(MemoryMoog, Prophet 5 and 10, and so on) to fatten them up! Jean‑Michel recorded his best album, Rendezvous, around the Synthex (check the track listings — it's the only thing on every track, and it provides the sound for the laser harp). Stevie Wonder had Elka cobble together a last Synthex for him two years after they stopped production when he used mine on the Characters album.

The Synthex had a nice implementation of pulse width modulation, oscillator cross‑sync, high‑pass and band‑pass filters, and it didn't go out of tune — but that wasn't why these guys gravitated towards it. They loved the chorus. Which makes it doubly amazing that it wasn't until the launch of the Roland D50, more than five years later, that full DSP effects became standard on a mass‑market synth (I suspect because of a combination of expediency and the falling prices of DSP chips). Roland did feature a chorus circuit on some of their Juno products, but all that did was allow a certain American synth designer to suggest that the Japanese had to put chorus on their synths because they couldn't make them sound good without it. The irony was that the year after this had been said, the same company launched a synth with a chorus circuit for every single‑oscillator voice — and you still couldn't make it sound good unless you stuck all six voices in unison on different patches and detuned them. So much for chorus as the panacea for thin‑sounding synths!

Those who tried switching off the effects on the Roland D50 soon discovered that they could be used to hide a multitude of sins. I did talk about this at some length last year, in the instalments of Synth School that covered S&S synthesis (December 1997 and February 1998), but for those who missed it, here's a quick recap.

The D50 came at a time when PCM ROM was still expensive by today's standards, so to save money the samples were split into two: an attack transient, which would stop abruptly, and a short loop for the sustained section, maybe as little as a single cycle in length. Each of these had to be played on a different oscillator (or 'partial', as Roland insisted on calling them), which meant that the loop had to start playing at the note‑on side by side with the attack transient. You could slow the attack of the loop's volume envelope, but you had to make sure the loop was at full volume when the transient suddenly stopped. If not, the volume level would drop massively as soon as the transient finished. Even if you got the loop attack just right, there was still a volume drop when the transient suddenly wasn't there any more.

Reverb As Foundation

Enter DSP effects as the solution. By putting a chip which could do digital reverb onboard, the D50 (for the first time ever in a synth), Roland could 'smear over' these sharp changes in level, rendering them (almost) inaudible. Because the reverb carried over the sound of the transient, it prevented the sudden level drop when only the loop remained. But the cosmetic effect was much more profound than just disguising the problem. Imagine a girl with a very beautifully shaped face but bad acne (I'm trying to remain politically correct here, but it's the only analogy I can find). If she puts on some very expensive foundation make‑up so that you can't see the acne any more, suddenly you see just how beautiful she is, especially if no other girl in the room is wearing any make‑up at all. This was the D50, with the small samples as the acne and the DSP reverb as the foundation, at a time when no other synth on the market had any built‑in reverb at all. It sounded so much more sophisticated than anything else, mainly because everything else you heard in a music store or elsewhere was usually dry. What probably started out as a real fire‑fighting solution ended up being perhaps the biggest asset of the D50, and the reason it sold so well.

What probably started out as a fire‑fighting solution ended up being perhaps the biggest asset of the D50, and the reason it sold so well.

Roland D50 synthesizer with its PG1000 programmer.

Roland D50 synthesizer with its PG1000 programmer.

Of course, the DSP on the D50 wasn't restricted to reverb. As had only been the case on free‑standing multi‑effects units before the D50, there was a full suite of digital effects, and you could use two at once. Obviously, the chorus could make single‑cycle loops much fuller, so chorus plus reverb was a popular combination. But that wasn't the end of it: there was distortion which, combined with reverb, yielded overdriven electric guitar sounds (almost regardless of what source sample was fed into the DSP); flanging and phasing; and delays and reflections for repeated phrases. Any effect to be found on a self‑respecting multi‑effects processor was included. The D50 began outselling other synths by a huge margin. Synthesis had changed for ever, and synths without effects were, for the most part, past their sell‑by date.

Other synth manufacturers went into overdrive (pun intended), desperate to get their own DSP effects‑equipped synths to market before Roland wiped the competition off the face of the planet. Korg were the first, less than a year later, with the M1, which had a couple of advantages over the D50. First, PCM ROM was coming down in price, so they went mad and used twice as much of it. This meant that the entire PCM source sound could be all on one sample (attack transient running naturally into the loop section), played back by a single oscillator. Although the M1 pianos and guitars sound very compressed by today's standards, because the sample goes into the sustaining loop very early (and the envelopes aren't accurate enough to reduce the volume naturally, as on an acoustic piano/guitar), the sound quality back then was unbelievable for a synth. This meant that the DSP effects on the M1 were used less for remedial purposes and more for simply placing a sound in a natural space and gently enhancing it.

The second feature of the M1 which was also a remarkable advance, although not totally unique, was its multitimbrality, with eight parts simultaneously available. One application of this was Combis, which allowed the stacking of any eight programs. This made for a big sound that was instantly impressive. Alternatively, eight Programs could be triggered on different MIDI channels or different tracks of the built‑in sequencer that made the M1 the first of the workstations. The sequencer itself was very powerful and, apart from anything else, made the M1 practically self‑demoing (spawning a whole new generation of lazy salesmen who just ran the demo sequences rather than figuring out the thing enough to play it themselves). But in the success which quality effects and multitimbrality brought the M1 lay the seeds of the biggest tech‑support nightmare since someone thought of putting a Local Off switch on MIDI keyboards.

8 Into 1 Won't Go

Keith Emerson (below) and Jean‑Michel Jarre (left), just two of the big‑name keyboard players to succumb to the appeal of Elka's early‑'80s Synthex, the first synthesizer to incorporate effects, in the shape of chorus. The Synthex features heavily on J‑M Jarre's Rendezvous album.

Keith Emerson (below) and Jean‑Michel Jarre (left), just two of the big‑name keyboard players to succumb to the appeal of Elka's early‑'80s Synthex, the first synthesizer to incorporate effects, in the shape of chorus. The Synthex features heavily on J‑M Jarre's Rendezvous album.

"When I put my synth into Multi Mode, it goes wrong/sounds funny/goes all small/loses its oomph." This complaint is enough to strike terror into the hearts of any synth distributor's tech‑support personnel. Why? Because an explanation of the synth's entire architecture is the only way to make the complainer understand that what they are describing is not a fault, but merely a characteristic of the synth's design. So, in an attempt to save the endangered sanity of my former colleagues in tech‑support departments everywhere (not least at Korg, where they still get 10 calls a day about M1s which are probably second‑, third‑ or fourth‑hand by now), here's the abridged version — suitable only for the more intelligent reader, something we can fortunately rely on here at SOS.

Each voice on the M1 (and many other synths of the same vintage) has its own oscillators, filters and envelopes, so anything you do with this sound‑generation circuitry is self‑contained. If each voice is playing a different Program (as happens in the variations on Multi mode), the oscillators, filters and envelopes can be set differently for each voice. However, there is only one effects circuit (through which all voices must pass). If the effects are using the settings for one of the single Programs, they cannot generate the separate effects settings required for another. So in Multi Mode, the same set of effects have to be used on all the different timbres.

The type of effects present on the M1 and others of its era are generally known as global or master effects. This means that they're added to the overall output of the synth, just as if you had plugged the main stereo out of the synth into a separate multi‑effects unit. Later synths added refinements, such as the ability to switch some sounds so that they didn't pass through the effects, or to send a different amount of each sound to the effects (we'll look at some of these evolutionary stages next time), but this is not the case for the first generation of synths with effects.

Synthesis had changed for ever, and synths without effects were, for the most part, past their sell‑by date.

Living With Global Warming

Roland's D50 pioneered built‑in DSP synth effects as we know them. As well as providing the sophistication of up to two treatments at once, the D50's onboard effects processor served to disguise the less‑than‑perfect sample‑based sounds of early S&S synthesis.

Roland's D50 pioneered built‑in DSP synth effects as we know them. As well as providing the sophistication of up to two treatments at once, the D50's onboard effects processor served to disguise the less‑than‑perfect sample‑based sounds of early S&S synthesis.

Adding effects globally to the output of a synth, whether it's just a touch of chorus and reverb to warm up the sound a little and put the instruments in a sonic space, or a more radical effect like distortion or flanging, can cause all sorts of problems — though it's better than leaving everything dry. Some of the standard components of a normal mix, such as the kick drum and bass line, are weakened and lose definition with more than a smidgeon of reverb, as reverb can make low frequencies woolly and almost inaudible in a mix. To get a electric guitar to sound at all authentic you might want distortion, but not if that means distortion on your drums and other instruments. How do you deal with this if you can't make some parts of your Multi dry or with a reduced send? Well, one solution is suggested in the 'A Global Problem' box...

Next time, we'll look at how the effects on multitimbral synths became more sophisticated, offering more options on send/return amounts and bypassing the effects completely on individual timbres. We'll also look at the introduction of insert effects which, on instruments such as Korg's Trinity, are really as good as separate outputs fed through a mixer and treated with external effects.

A Global Problem

It had a powerful sequencer and 8‑part multitimbrality, but built‑in effects also helped to make Korg's M1 a best‑seller.

It had a powerful sequencer and 8‑part multitimbrality, but built‑in effects also helped to make Korg's M1 a best‑seller.

If the M1 (or one of its contemporaries) is your only keyboard and you'd like to (cheaply) get around the inherent effects restrictions which can influence bass, drum and electric guitar parts especially, one idea is to pick up a second‑hand Novation BassStation to play basslines, triggered from the workstation's sequencer. This has no effects and will provide a good, dry, punchy sound (older monosynths, such as OSC's OSCar or similar, will do an even better job, but their second‑ hand value has rocketed in the last few years). For the kick drum, buy a cheap second‑hand drum machine and either trigger its kick drum from the sequencer or sync the drum machine via MIDI and program up the kick‑drum pattern. If you have a lead sound which requires distortion, use a monosynth through a £30 fuzz‑box.