The OP‑XY is a portable sequencing powerhouse.

I doubt I’m the only one who followed an arc from mad desire for Teenage Engineering’s OP‑1, to getting one, to discovering that what I really needed wasn’t a portable synth with a four‑track audio recorder but a portable synth with a multitrack sequencer. We got this with bells on with the OP‑Z, but I wished it had the same form factor as the OP‑1 with its own screen. The new OP‑XY delivers something close to this, evolving OP‑Z DNA into a workstation‑level groovebox/arranger, and leaving behind the motion graphics and lighting elements.

Let’s get the elephant in the room out of the way: the OP‑XY is expensive. Not that this is weird: people pay a lot for really nice instruments and outboard gear, but it inevitably informs how you evaluate this device. I was particularly interested to know if the OP‑XY has the power to replace a dedicated sequencer in a desktop rig. You might want to know if it can get close to, say, an Akai MPC level of DAWless production. Either way, most of us are probably looking at the XY lustfully, so let’s see if I can help justify an investment... or talk ourselves down.

Shades Of Grey

The OP‑XY is an eight‑part, multi‑engine synth and sampler, with 16 tracks of sequencing, split into two blocks of eight. The first eight are tied to synth or MIDI parts. The second eight (the ‘Aux’ tracks) access other features, like a CV/gate track, effects returns, performance effects and The Brain: an intelligent transposer.

Looks aside, this is a different approach to the OP‑1, which has multiple instrument slots but can only play one at a time. And although the OP‑1 has sequence players, the only way to capture anything is to record live into the four‑track digital ‘tape’ machine. The XY, like the Z, is multitimbral, with 24 voices dynamically allocated across eight parallel engines, powered by a dual‑core CPU and DSP coprocessor.

The XY has the same gorgeous housing as the OP‑1 and is roughly the size of a compact computer keyboard. The difference on the panel is that the natural keys have been shrunk to the same size as the accidentals to make room for a new row of step triggers. Visually the OP‑XY is differentiated with a greyscale design and an ombré gradient across the trig keys. This is mirrored by the high‑res screen, which, though capable of full colour, stays resolutely monochrome apart from some sparing use of red. Red means recording.

Connectivity comprises dedicated audio in/out and MIDI input on TRS mini‑jacks. Bluetooth MIDI and clock are available, but not Wi‑Fi. USB‑C provides charging of the internal battery, plus MIDI, audio and data interfacing. Then there’s an unusual multifunction output port that can be switched between audio, MIDI, CV and sync modes.

The keys feel like a computer keyboard but are velocity sensitive. The encoders are also buttons and have a clicky action, which is great for working with lists but makes synth tweaking inherently steppy.

The Samplers

New projects start with two drum tracks and a selection of instruments, but you can reassign the tracks freely. The drum sampler feels familiar from the OP‑1 Field, with 24 one‑shot sample slots that can be triggered or gated. Having a polyphonic kit of sounds taking up just one track offers a lot of scope for your productions.

A major improvement is that the drum sampler uses individual samples for each key instead of a single sliced file. You can load — and sample — into each key directly, and the XY has a proper sample manager on board. Like the OP‑Z, each track has a filter, and two sends to global effects.

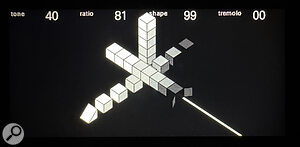

The vertical portion of the cross to the right‑hand side is a level meter, and the barely visible protrusion at the bottom left is a pitch‑bend pad.

The vertical portion of the cross to the right‑hand side is a level meter, and the barely visible protrusion at the bottom left is a pitch‑bend pad.

There are three low‑pass filter modes and a high‑pass to choose from. Apart from the whistly resonance on the ladder they all sound similar to me. Comparing them isn’t straightforward as, annoyingly, changing mode resets all parameters. The filter gets its own envelope. Usefully, there’s an additional static high‑pass filter tucked away in the instrument settings.

A significant limitation in the drum sampler is that, although each slot has its own pitch, mode and trim settings, all sounds share envelope and filter settings. This seems strange, as each voice has its own filter and VCA that follow the envelopes independently — it’s not a paraphonic situation. Hopefully this might be tweaked in the future.

The other thing that falls short compared to other premium sampling workstations is the lack of chopping/slicing functionality. To play chops from a sampled passage you need to fall back on copying the same sample to multiple keys and assigning different start points manually. There’s no option to time‑stretch for tempo‑matching chops or loops.

Two further sample engines are available. Sampler is the same as the OP‑1 sampler, providing chromatic playback of a single sample. Multisampler offers multiple key zones (but not velocity zones). The factory library showcases this with some lovely presets including strings and a piano. When building patches you can sample or load to a key and the XY will automatically create zones. When importing it will also set root pitches based on file names. Crossfaded loop points can be set, or read if there’s loop metadata.

The Synths

The eight synths are new to the OP‑XY, and are uniquely crafted sonic toys that defy easy definition. They use familiar synthesis schemes, but are preconfigured in particular ways and feature just four adjustable parameters with fun, and sometimes esoteric, animated graphics as feedback.

All the synths have four primary parameters and an animated display.

All the synths have four primary parameters and an animated display.

Despite limited controls, the synths reach a range of results, moreso than the handful of sweet spots on the OP‑1 synths. (The OP‑1 synths often give up controls to a filter and effect, which is not necessary here). I particularly like the Simple engine, with its charming but essentially irrelevant animation of descending slinkies, and the Wavetable engine, with its more informative oscilloscope. Wavetable features eight sweepable tables, with a Warp (symmetry/PWM) control and modulation. The Drift control goes up to sync’ed audio rate level, producing awesome phase modulation reminiscent of Native Instruments’ Massive. It would make a great standalone Eurorack module.

Modulation is less restrictive than on the OP‑1, as you don’t have to decide between MIDI and internal modulation sources. It’s still a single mapping within each engine from a source like the filter envelope, LFO, or the built‑in accelerometer, but having velocity as a second mod is great, and if you are playing the unit from an external keyboard you can add aftertouch, mod wheel and pitch‑bend to the mix.

Sequencing & Step Components

Each of the 16 tracks has a sequencer with independent length (up to 64 steps), scale (speed), gate length, quantise amount and groove depth. Note entry follows familiar conventions: you can record in real time, step record in stop, or select notes and drop them onto steps. Drum tracks show trigs from all sound lanes at once and there’s no on‑screen pattern display, but holding a note and tapping the Record button temporarily hides other lanes.

Parameter automation is captured during recording and it’s possible to write parameter locks by holding a step and setting a value. Lock points are treated as vectors, so automation glides between surrounding values. To achieve a more Elektron‑style lock you’d need to also anchor null values on the adjacent steps.

What’s really exciting about the OP‑XY sequencer is its step component system. I first encountered this idea on the OP‑Z, but have since found similar features on my main hardware sequencer (the Five12 Vector) as well as the Polyend Play, Intellijel Metropolix and Sequentix Cirklon. Step components are actions that can be added to specific trigs to modify their behaviour.

An example of something like this on many sequencers is probability: setting a chance for a given trigger to fire that’s evaluated each cycle. Ironically, the XY doesn’t do probability, perhaps to emphasise that there are more fun and musical ways to introduce variation. There are 14 step component types, each with 10 variations.

A suite of mix tools and MIDI effects make the XY eminently performable.The first three components provide the functionality I highlighted recently when reviewing Five12’s Vector, and that’s central to the RYK M185 and related Intellijel sequencers. These Pulse (repeat), Hold or Multiply (ratchet) steps. They can be used in combination (any step can have all 14 components active) and the first two push the length of your sequence longer than its nominal step count. Uniquely, you can set the value of these components to random, generating a new rhythm every cycle.

A suite of mix tools and MIDI effects make the XY eminently performable.The first three components provide the functionality I highlighted recently when reviewing Five12’s Vector, and that’s central to the RYK M185 and related Intellijel sequencers. These Pulse (repeat), Hold or Multiply (ratchet) steps. They can be used in combination (any step can have all 14 components active) and the first two push the length of your sequence longer than its nominal step count. Uniquely, you can set the value of these components to random, generating a new rhythm every cycle.

Pitch can be randomised within defined limits, or transposed, but my favourites by far are the ramp up/down operations. These are what the Metropolix and Cirklon call ‘accumulators’, walking a pitch up or down by a set amount each cycle. Portamento is also a step component, as is Bend which offers several pitch articulations. Tonality can be set to transpose by interval, in scale, or to ignore chord changes (more on that later).

Jump Step can send the sequence to a different place, pause it on the current step indefinitely, or (cleverly) realign the track when it’s gone out of phase. Another component sets a trig to play intermittently. Some components, you might think, seem destructive. Why not just change the pitch instead of transposing a fixed amount? And doesn’t setting a component to jump to an earlier step simply shorten the sequence? This is where the Component Skip component comes in, allowing you to set other operations on a step to only trigger every other time, or every third time, etc.

Bigger Picture

To progress your ideas there’s a structure of Patterns, Scenes and Songs. Arrange mode presents a horizontal row of clips representing the Patterns in your tracks. Multiple Patterns in tracks are shown as stacks, which fan out into a column when the track is focused. You can then use an encoder to flip between Patterns.

Shift and the numeric keys recall Scenes (up to 96), which store a combination of active Patterns, track mute and Brain states, and even which engine is assigned. Changes update the current scene destructively. Swapping Scenes, or Patterns within Scenes, is instant and playback continues from the current step, which is exactly how I like it.

Finally, Song mode: a 32‑slot grid where you can arrange a string of Scenes. Simply typing in numbers writes out the Scene sequence from the active step. Using the +/‑ buttons you can cue up a position in the Song during playback, and in this case the change waits until the end of the Scene. You can in fact create up to 10 different Song sequences within a project, and recall them from the bottom row of keys. You can set a Song running then switch to other views to play along, trigger punch effects and so on, although there’s no persistent indication of Song position.

Aux Tracks & The Multiport

Let’s jump back a bit as we skipped over the Aux tracks on the way to Arrange mode. I’m going to save Aux tracks 1 and 2 for a moment. Aux 3 is a dedicated MIDI track for playing, sequencing and controlling an external instrument. The four option pages provide channel, bank and program select, two sets of four CC controls, and a CC mod LFO.

At this point we can’t get much further without talking about the multiport. This is a 3.5mm TRS port that operates in a number of modes. Set to MIDI, it becomes a TRS MIDI output. Set to CV, it carries a combined CV and gate signal which you can access with a splitter cable. It also has modes for various flavours of analogue and Pocket Operator sync, and an audio mode. Aux 4 is the source used when the port is in CV mode. You can sequence CV here along with step components, although glide and pitch mods don’t work.

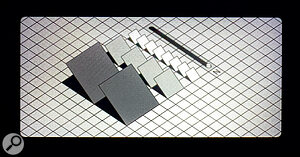

External sockets are found at the side and include a USB‑C port and 3.5mm sockets for audio I/O, MIDI in and a multi‑function MIDI/CV/sync/audio out port.

External sockets are found at the side and include a USB‑C port and 3.5mm sockets for audio I/O, MIDI in and a multi‑function MIDI/CV/sync/audio out port.

Aux 5 is an audio input. While testing the CV/gate output, I connected my external synth to the audio input and routed it through this track. This brought it into the mix and gave me access to the send effects, as well as a drive control. You can also use it for an external send loop through an effects unit or pedal. If you set the multiport as an audio output, all the instrument tracks get a third send that goes out via the multiport, then back in via Aux 5.

Aux 6 is Tape: not a tape recorder like on the OP‑1, but a sampling tape loop effect, familiar from the OP‑Z. This is particularly useful as a stutter and glitch effect, looping quantised slices of the sampled range triggered by the note keys. You can also do experimental stuff like warping pitch and time, and applying an LFO to parameters. Individual tracks can be included or excluded from the tape loop.

The last two auxes are effects returns. Although these default to delay and reverb, either can be swapped out for chorus, lo‑fi, distortion or phaser. It’s particularly effective to replace the delay with distortion or lo‑fi, as the OP‑XY can sound pretty clean. This lends itself to beautiful ambient tracks, but if you want something that will shake the floor a bit you can grunge things up here.

The Brain & Punch FX

Looping back to Aux 1 and 2, we have some OP‑Z‑style magic with The Brain, and Punch FX. These complete the workflow picture for the OP‑XY, providing performable (and sequenceable) real‑time progressions, variations and fills.

The Brain is a transposition engine that detects the key and scale of your project then lets you manipulate it in musically coherent ways. For example, it may decide that your piece conforms to C major. The Middle C key will become the home position for playback in The Brain. If you hold the E key above Middle C, your piece will play back two tones higher diatonically; that is to say, still using the notes in the C major scale.

It was slightly confusing figuring this out as The Brain expresses what it’s doing in terms of modes. So in the above example, the Brain will say it’s moved to E Phrygian, which is a fancy way of saying the notes of the C major scale starting from E. It’s easier to spot if you move to A, as it shows this as a transposition to A minor, which shares the same notes as C major.

You can be more prescriptive about what Brain does. First you can specify the key and scale instead of letting Brain guess. Second, if you hold a chord instead of a note, you can force progressions that break out of the base scale, for example moving from major to minor on the same root.

Brain provides a new yet oldschool way of working that I really got into. You can capture some simple sequences like a bass line and a single held chord, then create a chord progression in Brain. Just turn the scale (speed) of Brain’s sequence track right down and sketch out song sections on a single page. Then string together multiple Patterns into a song, all in one track. You can choose which tracks are included: Tracks 1 and 2 default to off, for example, as they get preloaded with Drum Samplers. One large omission is that the Aux MIDI and CV tracks are not affected by The Brain, which limits this workflow when using external instruments. However, it does work over MIDI sent from the main tracks.

If you’ve played with the OP‑Z, Pocket Operators or the EP‑133 you’ll know how great Punch FX are. The Aux 2 track on OP‑XY is dedicated to these momentary performance modifiers. Every note key holds one of the effects, which range from stops and stutters to rhythmic and melodic variations. There are 12 effects, repeated across the two octaves of the keyboard, allowing the Aux 2 track to apply Punch FX to melodic and percussive tracks as separate groups. (The distinction is also used by the master section of the mixer to balance drums against other instruments). It’s possible to apply (and sequence) the Punch FX to any track individually while it’s focused.

Conclusion

The OP‑XY is deep, and I’ve not even covered some key features like players, grooves and tuning schemes. It doesn’t have the level of core beatmaking, production and fine editing potential as an MPC or Maschine, but at the same time its dynamic, modular‑inspired sequencing makes these classic workstations look staid. I was excited to see how much the sequencer could be used for external devices, and was disappointed to learn that the multiport can only do one thing at a time. It’s great that it can do CV, and incorporate external processing, and MIDI, but only one of these at a time. This is mitigated by being able to use any track for MIDI, and as I discovered, you can connect a USB thru device like the Retrokits RK‑006 to break out to multiple externals.

I had endless fun setting up short, simple sequences, loading them up with components like the pitch ramps, mapping out a Brain chord progression, then seasoning with Punch FX.

Unless a classic linear recording workflow appeals to you, the XY is way more accessible and productive for creating songs and performances than the OP‑1. The Brain and step components make the OP‑XY both a generative sequencer and songwriting assistant. I had endless fun setting up short, simple sequences, loading them up with components like the pitch ramps, mapping out a Brain chord progression, then seasoning with Punch FX. It is however a closed environment at the moment in terms of progressing a project. There’s no way to export or bounce stems, and no multi‑channel USB output.

So, the OP‑XY doesn’t qualify as the mythical ‘one device to rule them all’ if that’s how you’re hoping to fund it. But it must be the most functional dedicated device of its size, it’s a beautiful thing, and it certainly inspires you to make music.

Pros

- Fantastic sequencing with step components and performance effects.

- Unlimited step components per step.

- Rich range of sampling and synth sources.

- Per‑scene engine assignments.

- Brain and Punch FX generate interesting tracks from simple starting points.

Cons

- No export or multi‑channel output.

- Brain doesn’t work with the Aux MIDI/CV outputs.

Summary

A genuinely useful and accessible portable workstation, marrying the OP‑Z’s sequencing with the OP‑1’s beauty.

Information

$2299

When you purchase via links on our site, SOS may earn an affiliate commission. More info...