Former Savage Garden singer Darren Hayes has turned his back on major labels and hit–factory songwriters to pursue his love of electronica — with help from producer Justin Shave, a vintage Fairlight and a unique computer–based instrument.

“My previous album was the best–reviewed and worst–selling thing that I have ever made, but it was my proudest moment,” insists Darren Hayes, reflecting on the reception received by his second solo album, The Tension And The Spark. “It was an album in which I purposely tried to find a new direction and worked with incredible technicians of experimental electronic music like Marius de Vries. Like most brave things you do in life there’s a risk, and the one I took was moving away from a commercial pop sound and potentially terrifying my record company. What that process showed me was that my love of production and electronic music was not just a fad — it was a second part of my career.”

“My previous album was the best–reviewed and worst–selling thing that I have ever made, but it was my proudest moment,” insists Darren Hayes, reflecting on the reception received by his second solo album, The Tension And The Spark. “It was an album in which I purposely tried to find a new direction and worked with incredible technicians of experimental electronic music like Marius de Vries. Like most brave things you do in life there’s a risk, and the one I took was moving away from a commercial pop sound and potentially terrifying my record company. What that process showed me was that my love of production and electronic music was not just a fad — it was a second part of my career.”

In commercial terms, the first part of Darren’s career could hardly have been more successful. In the late ’90s, his band, Savage Garden, which he formed with instrumentalist and producer Daniel Jones, had a string of huge hits, not just at home in Australia, but all over the world. ‘Truly Madly Deeply’ topped the US charts in 1998, and at the height of their fame they performed to the world during the closing ceremonies of the 2000 Sydney Olympics, but Hayes decided to bring things to a close the following year to pursue his own projects.

After the split, Darren quickly announced his first solo album, Spin, in 2002, and had a hit with ‘Insatiable’. He remained with Sony BMG subsidiary Columbia Records for The Tension And The Spark, but its relatively experimental content did not impress his core audience. Still wanting to capitalise on Darren’s pop-star status, record company and management pushed him to work with a host of established producers and hit songwriters. “Coming off the back of The Tension And The Spark,” explains Darren, “I felt lost and was subconsciously thrown for about a year. I sat with teams like The Matrix, Rob Davis and all of these superstars and came up with perfectly functional, fun pop songs — but they didn’t mean anything to me!”

After the split, Darren quickly announced his first solo album, Spin, in 2002, and had a hit with ‘Insatiable’. He remained with Sony BMG subsidiary Columbia Records for The Tension And The Spark, but its relatively experimental content did not impress his core audience. Still wanting to capitalise on Darren’s pop-star status, record company and management pushed him to work with a host of established producers and hit songwriters. “Coming off the back of The Tension And The Spark,” explains Darren, “I felt lost and was subconsciously thrown for about a year. I sat with teams like The Matrix, Rob Davis and all of these superstars and came up with perfectly functional, fun pop songs — but they didn’t mean anything to me!”

Instead, Darren parted company with Sony, relocated to London and began making the epic This Delicate Thing We’ve Made, a two–CD, 25-track album with a conceptual theme and electronic sounds from the ’80s.

A Close Shave

To get a sense of exactly what sort of music he wanted to make, Darren prepared a compilation of his favourite songs and moods and analysed the result. Although the material spanned a couple of decades he recognised some consistent themes, and concluded that a Fairlight Computer Musical Instrument would provide the sound he wanted! Darren’s next move was to find a collaborator who had the technical ability to help him realise his ideas. Rather than hiring a well–known producer, he chose Justin Shave — a substitute keyboard player on a concert tour, who had caught Darren’s eye when using his own custom–designed music production system, the Okkam 01 (see the ‘OK Okkam’ box elsewhere in this feature), built using Native Instruments’ Reaktor software.

“I’d heard he’d done a lot of dance music and some for film,” says Darren. “He was backstage at the Apollo playing with this Okkam thing, twiddling knobs and faders with his headphones on and I remember being vaguely fascinated with him, thinking ‘Who is this man? Why isn’t he rehearsing for my show? Why doesn’t he seem nervous?’ It was because he’s an incredible player and we became friends. A year later I sat him down in my lounge and told him my idea for this record. I said ‘It’s not the production I want, but there’s a feeling and a narrative and I want to base it all around the Fairlight.’”

Although Justin hadn’t produced an album of that kind before, he didn’t pass up the opportunity and took the plunge. Justin recalls that as soon as he agreed, Darren went on eBay and bought a Fairlight CMI Series IIx, a model originally released in 1983. It was then handed over to Justin to master while Darren headed to Phoenix in Arizona for a month to complete a project he’d begun with The Tension And The Spark producer Robert Conley. Justin’s other brief was to find a suitable studio space, which he eventually did at Mayfair Studios in Primrose Hill.

Raising Arizona

At the time of Darren’s Phoenix visit, he felt that his working relationship with Robert Conley was more or less over, and that it was just a matter of fulfilling his obligations. However, when he told Robert about the Fairlight the producer enthusiastically plugged in an old Ensoniq keyboard, demonstrated some drum sounds and kick–started a creative spell of songwriting. “As a kid I liked things like Prince’s Sign Of The Times, that was essentially just him and a drum machine,” explains Darren. “The quality was like a bootleg and it was an intensely personal, simple record. As my tastes became more eclectic, I also started to look up to artists like Peter Gabriel and Kate Bush. I was playing Robert tom fills and percussion sounds in songs like ‘Running Up That Hill’ and ‘Cloud Busting’, and recognised that the Ensoniq’s palette was similar. Then he pulled up a virtual plug–in of the Fairlight and I got really excited. We wrote ‘How To Build A Time Machine’ and I realised that it was the sound I wanted for this record. I thought ‘This is the weirdest song I’ve ever written, but it needs to be on this record.’

Justin Shave in his studio.“I’d amassed about 30 songs over the previous two years and I probably rejected 25 of them because they didn’t sit. Robert and I wrote five that formed the crux of the conceptual part of the record — songs that dealt with this idea of going back in time, whether it’s through the Fairlight and Ensoniq sound palettes, or emotionally and lyrically with me talking about going back to my childhood and fixing things.

Justin Shave in his studio.“I’d amassed about 30 songs over the previous two years and I probably rejected 25 of them because they didn’t sit. Robert and I wrote five that formed the crux of the conceptual part of the record — songs that dealt with this idea of going back in time, whether it’s through the Fairlight and Ensoniq sound palettes, or emotionally and lyrically with me talking about going back to my childhood and fixing things.

“There was a slight conceptual theme on Prince’s Sign Of The Times and certainly on Hounds Of Love that I toyed around with, but I didn’t want to make either a concept or pop record. I needed a device to carry some kind of narrative, and the idea for a double album stems from vinyl where there are two distinct movements. There was talk of making one side a Victorian science–fiction theme and the other a dance–flavoured pop record but, at the end of the day, it is about relationships and the differences become more interesting side by side. I hope that the concept is subtle and not in your face.

“I took those songs back to Justin and we spent three months creating a body of work in Primrose Hill.”

Reinventing The Reel

By the time Justin got his teeth into the project, Darren had amassed quite a disparate collection of material through his collaborations with Conley and other production teams, some of which was in the form of rough demos comprising drums, bass, guitar, keyboard and vocal. Justin’s task was to take the production ideas from Darren’s mix tape and apply them to the existing material, while incorporating sounds from the Fairlight and his own production palette. Justin explains how he did it. “I’d listen to a bunch of songs and soak up all of the micro–elements Darren liked. Then I’d take the elements, reinvent them and incorporate his song into that invention! Where there were existing demo recordings, the instrumentation was generally replaced by programmed material. A lot of the demos were middle–of–the–road setups, just basically getting the song down. Some he’d written with other writers who’d done a bit of production and sometimes the seeds of the track were already there, but I wanted to make it more produced and epic–sounding. ‘Who Would Have Thought’ is an example of one where the vibe was already there but I took the demo into the melting pot and started again.”

Seven of the tracks that eventually made it onto the album were co–written by Justin and came about from Darren reacting to one of the grooves Justin generated from within his Okkam machine. “I’d be working on a basic vibe using a four- or eight–bar loop,” says Justin, “then Darren would come in fresh from the gym and go ‘Wow, what’s that?’. ‘Conversation With God’ was the first song we did together. I was just testing the Fairlight and wrote this random repeating riff when he said ‘What’s that? It’s really gorgeous.’ I told him it was just a test but he said ‘No, let’s write a song over it.’”

Fresh in Darren’s memory is how much time was spent experimenting with sounds and grooves. “Sometimes Justin spent six hours just with the Okkam on a loop, filtering through its list of possible options,” he recalls. “I never wanted my record to be happening without me, so I would sit listening to drum beats and sounds until something excited us. There was a lot of Justin apologising and saying ‘I’ve just got to get this right,’ and me saying ‘I want you to go through this process.’ He was very welcoming of my interest and curious about what my instincts were. I was relating to sounds and techniques as a fan so I would present something, he would find out what it was about it that I liked and then work that out. It was from those production experiments that we wrote seven songs, and I kept rubbing others off the album to replace them with our songs.”

Clunky But Beautiful

More aware of the Fairlight’s status than its sounds at first, Justin soon began to appreciate its unique qualities. “It’s a clunky bit of technology with its IBM mainframe humming away underneath the desk, but it does this airy, crunchy sound that you can’t get with newer gear. I was attracted to that, and pads in particular sound really beautiful.”

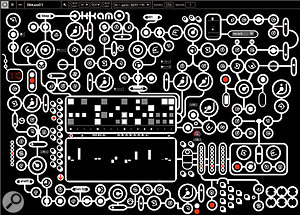

Part of the point of Justin’s Okkam 01 instrument is that its interface can be projected to add visual interest to a performance. This patch is called ‘Aphex Beat Man’.

Part of the point of Justin’s Okkam 01 instrument is that its interface can be projected to add visual interest to a performance. This patch is called ‘Aphex Beat Man’.  This blueprint shows all the Okkam controls as they are laid out on the hardware surface. It soon became apparent, however, that the Fairlight’s floppy drive was somewhat temperamental. The situation injected a bit of chance into the creative process, but far from deterring Justin, it fitted in perfectly with his working methods. “I’m a big, big fan of happy accidents! I think that is where all the magic happens in the studio. What would actually load depended on what we booted up on a particular day and that dictated what sounds we used.

This blueprint shows all the Okkam controls as they are laid out on the hardware surface. It soon became apparent, however, that the Fairlight’s floppy drive was somewhat temperamental. The situation injected a bit of chance into the creative process, but far from deterring Justin, it fitted in perfectly with his working methods. “I’m a big, big fan of happy accidents! I think that is where all the magic happens in the studio. What would actually load depended on what we booted up on a particular day and that dictated what sounds we used.

“We started out using the Fairlight snare and tom presets, but I quickly got bored with that when the disk drive stopped working, so we loaded the sampler page to try recording Darren’s vocal. It’s only got about two seconds of sampling time so all we could manage was an ‘Er’ or ‘Ah’ sound, or a word, and at the end the sample would cut out with a pop or a click. The Fairlight mapped those sounds up and down the keyboard, but the weirdness of the samples at different pitches sounded really interesting so I recorded those back into Pro Tools, together with the pops and clicks, and ended up putting them into the Okkam and building rhythms out of them.”

The Road Less Travellized

A major theme throughout the album is the use of pad sounds generated from synthesizing Darren’s vocals, the idea being to subliminally expose the listener to the voice throughout the record. For this, Justin used his classical music training and experience making dance records to create a meditative effect, arranging the parts with certain intervals. Perhaps the clearest example of this effect is at the very beginning of the first song, ‘Fear Of Falling Under,’ created using a NI Reaktor plug–in called Travellizer. Justin explains how he did it. “It’s an intensive but worthwhile process. I recorded Darren going ‘Aaaaaaaa’ in lots of different keys and built the chords from those in Pro Tools. Then I ran those chords through the Travellizer to find the nice–sounding loop points and then re–recorded that all down again. The software kind of loops a vocal sample back on itself and then adds a whole bunch of reverb and delay. There’s no click or crossover point, so you can layer up vocals over and over again. Then I’d often put them through a Reaktor plug–in called Fast FX, which does all manner of stuff!”

One of Justin’s favourite dance production techniques, applied to great effect on the track ‘Step Into The Light’, is to send a lush pad sound through a compressor, but feed a rhythmic kick–drum pattern into the compressor’s side–chain to act as the trigger. Naturally, this is something he has designed his Okkam to do efficiently. “I’m a big fan of that sucking sound where the compression takes the attack out of the pad, leaving it to come back in. I wanted a way of doing that quickly, instead of taking 10 minutes pulling up Bomb Factory in Pro Tools, so I’ve assigned a compressor in the Okkam to take a feed from whatever drums you want, so I can do it just by turning a knob.”

“The effect Justin calls the suck is one of the most interesting aspects of that song,” enthuses Darren. “It gives the pad washes a rhythmic wave quality. I realised that it was something I loved about a lot of French dance music. Stuart Price used it a lot on the songs he produced for Madonna’s Confessions On A Dance Floor.”

Rock & Rola

The Rola tape recorder, with built–in radio and loudspeaker, was used on a number of tracks on the album.As someone particularly open to the effect a chance discovery or accident can have on the direction of a piece of music, Justin made the most of it when a friend dumped some old analogue tape machines in his studio. The item that ended up in use on the album was a ‘60s–made Rola field recorder, complete with its own speaker and radio! “You’re supposed to record interviews on it and use the speaker to check what you’ve recorded,” says Justin, “but you can also record the radio to tape. On the day of the London bombings, as an exercise, I turned the radio on, recorded different news reports and forgot about it until Darren came into the studio. I played back all these recordings and we used those to write ‘Bombs Up In Your Face.’”

The Rola tape recorder, with built–in radio and loudspeaker, was used on a number of tracks on the album.As someone particularly open to the effect a chance discovery or accident can have on the direction of a piece of music, Justin made the most of it when a friend dumped some old analogue tape machines in his studio. The item that ended up in use on the album was a ‘60s–made Rola field recorder, complete with its own speaker and radio! “You’re supposed to record interviews on it and use the speaker to check what you’ve recorded,” says Justin, “but you can also record the radio to tape. On the day of the London bombings, as an exercise, I turned the radio on, recorded different news reports and forgot about it until Darren came into the studio. I played back all these recordings and we used those to write ‘Bombs Up In Your Face.’”

The track also benefited from some old Roland TR808 recordings discovered quite by chance on one of the Rola tapes. These were used as the basis of the song’s drum and bass parts. Justin also noted that the hot recording level of the 808 tracks had resulted in distortion and, inspired by that, replicated the affect on some of Darren’s vocals. “I saturated his vocal for the song ‘The Only One’. We recorded them in Pro Tools first, then bounced them onto tape, turned up the speaker on the front, put the machine in the vocal booth, played back the tape and recorded the result. That gave us the warm telephone effect. Darren was initially freaked out about it but he took the demo home and liked it.”

A New Voice

For most of the album Darren’s vocals were recorded using his microphone of choice, the Neumann U87, together with a Focusrite ISA220 Session Pack. In Phoenix the chain only differed in that Conley also used a Groove Tubes Vipre preamp. Although Darren was happy for Justin to experiment with musical textures and beats, he was initially unwilling to give up control of his trademark vocal sound, which had been produced a very particular way for many years. Justin, however, felt that there was more to be had. “When we first started recording he gave me a bit of critique and asked me to try some ideas,” explains Darren. “I was thrown by that and we had our only argument. I said ‘Don’t tell me how to sing because it’s what I do and I’ve produced my vocals for six years!’ He said ‘OK, I thought that was what you wanted me to do as a producer.’ I went into the booth, tried some of his suggestions, pressed the talkback button and went ‘I’m really sorry, you were right.’ From that moment I started to trust him and let go of a lot of control over how my voice should be presented.

“One of his first rules was to not use Auto–Tune. I don’t need to but I am such a control freak that, if there was one slightly sharp note, I didn’t want to have to deal with it. Justin was one of the first producers in a long time who told me I could sing it better.”

As well as the performance, Justin was also keen to push the production sound of Darren’s vocals, so that it would fit in with the electronic feel of the record. “He was used to just standing in front of a microphone and someone pressing Record,” says Justin. “You can tell from the Savage Garden records that there’s not a lot of sideways thinking in the treatment of his vocal. It’s all pretty much one sound. I really wanted to explore where I could take his vocal and I think he was happy with that once he trusted me to do it.

“Generally I’d work on a track and he’d sit on the couch humming ideas. When he was almost there, we’d try it out in the control room and maybe I’d make some chord changes. If we were happy with the arrangements he’d go into the studio and sing two or three takes. A lot of the vocals were done pretty much with no drop–ins. He is an excellent singer so there wasn’t any need to do that.”

“I got him singing falsetto, which he’d never done much before. I pitched his vocal up and down in ‘Bombs Up In Your Face’ and ‘Me Myself And I’ and changed the formant using Celemony Melodyne and Waves UltraPitch. I also vocoded it with Waves Morphoder and NI Reaktor’s vocoder.”

“Although it’s an electronic record we’ve tried to keep the soul of the performance,” adds Darren, “so the idea of cutting and pasting, whether it be a backing vocal or a keyboard riff, was thrown out of the window. There is quantising and all sorts of tricks of the trade, but these are still performances with a narrative and an arc.”

Delicately Mixed

As each song was completed, Justin created rough mixes using his Mackie 24:8 mixer. Darren describes the results as “amazing” and agreed that the balance and levels should be carried over into the proper mix sessions, which took place at London’s Eden Studios. Having spent so long developing a particular sound for the record, Darren and Justin wanted to ensure their vision was realised, so the pair joined engineer Ash Howes in the studio for the month–long process. “It was vital that Justin be there for every step because, from a dance point of view, the rhythm section was crucial,” insists Darren. “I was looking for an engineer who would be comfortable with the fact that we had a clear idea of how it should sound and one who could commit to the whole project.

“I loved Ash’s Kylie mixes and had it in my mind that he was capable of doing something very lush. In my book, reverb has been a dirty word for five years — it’s been about dry squashed vocals — but I wanted this record to have space. Ash worked a 10am till 8pm day so we’d come in the next day, really listen to the mix, tweak it, print it and move on.”

Darren Hayes (left) and Justin Shave at work on This Delicate Thing We've Made.From Justin’s point of view, the mixing process enabled the team to make more polished versions of his Mackie mixes. “I don’t see mixing as separate from recording,” he says. “It’s more of a reviewing process — a second look or fresh perspective, fixing up any mistakes and using some really expensive gear! Darren’s vocal was the main thing I wanted to address. I wanted Ash’s experience and he used a specific chain on pretty much all Darren’s vocals. I know there was an [Empirical Labs] Distressor and a Pultech EQ unit involved and it was mixed on an old SSL G–series desk. I’m in love with its bus compressor. It does something to drums, I don’t know what, but it sounds brilliant! I only have eight channels on the Mackie, so the separation was good to have. On ‘Walk Away’ we maxed out at 120 tracks.”

Darren Hayes (left) and Justin Shave at work on This Delicate Thing We've Made.From Justin’s point of view, the mixing process enabled the team to make more polished versions of his Mackie mixes. “I don’t see mixing as separate from recording,” he says. “It’s more of a reviewing process — a second look or fresh perspective, fixing up any mistakes and using some really expensive gear! Darren’s vocal was the main thing I wanted to address. I wanted Ash’s experience and he used a specific chain on pretty much all Darren’s vocals. I know there was an [Empirical Labs] Distressor and a Pultech EQ unit involved and it was mixed on an old SSL G–series desk. I’m in love with its bus compressor. It does something to drums, I don’t know what, but it sounds brilliant! I only have eight channels on the Mackie, so the separation was good to have. On ‘Walk Away’ we maxed out at 120 tracks.”

To master the album, Darren deliberately chose Metropolis’s Tim Young, having read an article he’d written on the over–compression of modern records. “Mastering engineers hate it and radio stations and record companies love it,” says Darren, “but on a subconscious level there is something homogenising about it, so we made a concerted effort not to make a record like that.

“This record is relatively quiet and dynamic and has quite a lot of headroom. It was very important to me that the quiet moments would be terrifyingly quiet, so that the loud parts would then have room to build.”

Proud Parent

From Darren’s frequent references to The Tension And The Spark being his “worst selling record” it’s obvious that coming to terms with commercial disappointment has been difficult for him. Nevertheless, he is also adamant that his darker and more experimental work is not just a phase, and seems truly proud of the new album and what it stands for. “It’s a real commitment to ensuring that everything that I leave on the planet is something I’m proud of sonically. I’ve been successful in making records that sold a lot and loved them at the time, but I’ve also loved the opportunity to grow up, change and become more interesting. If becoming more diverse means that I don’t fit in commercially, then it is a pretty fair trade. I absolutely love playing these songs. It’s a pop record but I like to think that it is an intelligent one with hand firmly on its heart. There was a point where we though about making the record in a bedroom but decided to rent a nice room and have it be a pleasurable experience. And making this record was one of the happiest times of my life.”

OK Okkam

The Okkam 01 combines a Mac running NI Reaktor with a custom–built control surface.With the possible exception of the Fairlight, it was Justin Shave’s custom–built Okkam 01 which most influenced and shaped the sound of This Delicate Thing We’ve Made.

The Okkam 01 combines a Mac running NI Reaktor with a custom–built control surface.With the possible exception of the Fairlight, it was Justin Shave’s custom–built Okkam 01 which most influenced and shaped the sound of This Delicate Thing We’ve Made.

Playfully named after the Occam’s Razor principle, generally attributed to 14th–century philosopher William of Ockham, Justin’s 01 was invented as a problem–solving device, bringing together his sample library and favourite production tricks into one user–friendly box. The software part runs on an Apple Mac and was designed using Native Instruments’ Reaktor 5 modular sound studio, in which seven distinct modules were assembled and networked. These include a sequencer, drum machine, bass section, soft synth menu, a sample library and ‘chordal/harmonix’ section, plus a host of effects processors, all of which are accessible via a single user interface, enabling Justin to combine them in a variety of ways and to introduce randomness into the creative process.

“I made it during a very boring and depressed winter in 2005 when there wasn’t much work. In Australia the sun would be shining so we’d have a barbecue, or be doing some shit besides sitting in the studio! I built it as a live tool, although I’ve never actually used it live because I’ve been working on Darren’s album! With Reaktor you can basically build anything in the digital realm.

“I was getting into Ableton Live but came up against performance limitations. It’s all very well triggering loops but I wanted to get inside the music while it was playing. For example, I might want to record a keyboard or bass sound, have that play along and then change the kick and snare sounds on the fly or improvise. I designed the user interface to look interesting because I was sick of shows where people were just twiddling with their laptops, so it’s intended to be projected up onto a big screen. When I turn the physical knobs, the virtual ones do the same.

“Then I realised that I could only turn one knob at a time with a mouse, so I entrusted my good friend, Tom, an electronics engineer, with soldering together a MIDI controller with about 60 knobs, 20 sliders and lots of buttons and flashing lights.”

Over a 10–year period Justin had amassed quite a collection of samples, which he wanted to be able to access in a dynamic and creative way. His Okkam design provided him with a way to do that. “The harmonix section basically references a massive sample bank of chords played on various different instruments. It includes filtered stuff and weird sounds I’ve produced over the years. You draw on an X–Y grid and that determines which particular sample will play at that time. Every sound is mine but it provides a new way of realising it. You can also draw in the matrix and it will come up with different chord sequences that you’d never have played yourself.

“There’s also a random thing contained within a knob which shifts the entire sample bank up and down. For example, if you turn this knob it still plays the same rhythm but it will reference a completely different area of the sample bank.”

Justin specifically designed the Okkam to include all his favourite dance production tricks, and has certain pre–configured routings set up for fast use. “I’ve got this side–chaining thing coming in from the drum machine inside the Okkam which affects the way the samples play, so you can change the attacks, the decays and filters. I have control over the actual start point of the sample triggering within separate samples, so there is an infinite variety of stuff that you can do just by twiddling a couple of knobs. If something sounds completely shit I can turn the knob, get something new and start again. I never tire of the sounds because I’m frequently updating the sample map or the way things are digitally joined up inside.

“The Okkam is self–contained and designed so that an entire track can be run out of its two outputs. You need a very fast processor to run it. ‘Me Myself And I’ is an example of using the whole instrument to produce a track. On some of the other tracks I just used the drum or the chordal or bass line bits. The idea is that when I’m doing it live I can have a whole track in front of me and reference any part of it at any time — tweak the bass drum, snare, or change the chords by pressing a few buttons.”

Going Solo

Since his last album, Darren has become an independent artist, creating his own Powdered Sugar label for the release of This Delicate Thing We’ve Made. He explains how he came to reject the major label system this time around. “At first I was terrified, because I presumed I was going to get a deal for this record and sell it on. But as the conceptual time-travel idea started to emerge I was definitely aware that the path I was taking was making it harder and harder to take to a new label. I did meet with Angel — a tiny offshoot pop label of EMI — who we brought in on the latter half of the recording process. They got really excited but I shut down the process when they started saying ‘We really love it but can we have copies to give to our executives to see if they can live with it?’ I thought, ‘I’ve passed that point. I’m making this record the way I want, I’ve hired the mix engineer and the people I want, the song sequence has been on a white board for several months and I have the front cover.’ Certainly for new bands it’s essential to have promotion and the money behind you but I’m lucky that I had that commercial success as a younger artist. I now look up to people like Peter Gabriel who do their own thing. It’s not an easy path, but the idea of being in the major label system at this point in my career seems totally ludicrous.”

Native Man

Although This Delicate Thing We’ve Made was recorded using quite a number of vintage analogue synthesizers, Justin Shave leaned most heavily on Native Instruments’ range of software instruments. “When Massive came out I thought it was very much like Reaktor, although it’s a bit more polished and interesting–sounding. I’m not one to use presets but the track ‘Setting Sun’ is just one patch out of Massive! I loved this so much and I’d never heard it coming out of a soft synth before.

“NI’s Akoustik Piano is very realistic and I find that it responds well. For a long time I got my piano sounds from my Nord Lead II but if I need a sound that’s really realistic I go to Akoustik. It has all those nice touches where you lift up the pedal and it makes a noise like the dampeners are going down on the strings. The track ‘Words’ is just Akoustik Piano and vocals. When Ash was mixing it he didn’t realise it wasn’t real and asked where we recorded it!”

“I’m also obsessed with the synths you get with Reaktor. There’s a massive user group on the web where people design their own synths. I downloaded loads of those and I’m constantly impressed with the variations you can get.”

The basic building blocks in Reaktor 5 are called Ensembles and are available in a library. Justin highlights some that were used on This Delicate Thing We’ve Made.

‘Junatik’ was used for automated filter pad sweeps and percussive synth sounds, ‘Sine Beats 2’ for quirky atmospheric rhythm mixes and ‘Newscool’ just for mad, mad rhythms. ‘Vectory’ was useful for creating massively time–stretched drum-loop samples to play tones and denote key. ‘Analogic Filter Box’ is great for cool envelope–following filters and ‘Banaan Electrique’ for dirtying up those all–too–clean sounds.”