Steven Wilson in his home studio.Photo: Lasse Hoile

Steven Wilson in his home studio.Photo: Lasse Hoile

Prog-rock wunderkind Steven Wilson is using his studio skills to give legendary rock albums a new lease of life.

"The equivalent of polishing the Sistine Chapel, that's what I feel I'm doing sometimes with these classic records." Steven Wilson is talking about his remixing work, which he began in 2009 as a sideline to his very successful career as a musician and producer. So far, he's polished classic records by King Crimson, Roxy Music, Jethro Tull, Yes, XTC, Tears For Fears and more, creating new stereo and 5.1 surround mixes that have been generally praised by fans and critics.

He says this sideline has grown to take up maybe a fifth of his working life, and has recently developed a laptop setup that means he can do much of his remixing during otherwise dead time on his extensive tours. So far this year, he's played over 60 concerts in Europe and North America, with a further 60 or so slated toward the end of 2018 and into 2019 in Japan, Australasia, North America and Europe.

"If I've got a couple of days off in a hotel and time to kill," Wilson says, "I can load up an album remix project and start to piece it together. I can't create definitive mixes, and obviously I can't do the surround mixes, but I can do a good 60 percent of the work sitting in a hotel or dressing room: editing, compiling, getting basic balances, figuring out stereo placement on the original mixes. So although I'm busier than ever in my own career, I'm managing to maintain the remix work too. I'm becoming more selective about what I take on, though, because I'm in the fortunate position of being offered more and more projects. But then I've only ever wanted to remix things that I have an affinity with, whether it's an album I grew up listening to, or one that I can genuinely say I love — and with nearly all the projects I've taken on, both are true."

Five Steps To Audio Heaven

A typical Steven Wilson remix goes through five stages. First, he receives a commission from a record label or a management company; the choice of album is often connected to a meaningful anniversary, or to an artist gaining new rights to their back catalogue, or a back catalogue being acquired by a different label.

Next, the commissioning company locates the relevant multitracks, which is not necessarily a straightforward task. "For example, at one point I was asked if I wanted to remix the back catalogue of a legendary rock band, but they just couldn't find enough of the tapes," Wilson says. The other factor here is fiscal: every visit to the tape library or archive is usually at a cost to the company. When the tapes are located, they are baked, directly transferred to 96kHz, 24-bit digital files, and supplied to Wilson as a complete set of raw WAV files. "So if there's 10 minutes of test tones on the tape, I'll get that," he explains, "or if there's 10 minutes of silence at the end of the reel, or of the band tuning up, that will also be part of what I receive."

The number of files he gets matches the number of tracks on the tape. "So I might get eight files, 24 files — or, in one case, 72 files," he adds with a smile. He also gets scans of the tape boxes, where available, as sometimes they can reveal useful information about which takes were used and so on.

The third step is to listen to what's been transferred from the multitrack reels in order to identify the master take. This often long process can be a mixture of revelation, as when he discovers unreleased material, for example, and tedium, such as listening to the band going through 27 false starts or mis-takes. "Sometimes there can be multiple takes that were compiled to create the finished master," he says. "So you might find a particular master is half of take five and then the second half of take 12, and then it might cut back to take five for the last four bars — whatever it is. So at this stage I'm figuring out what the master takes are. I then compile a session where I have all the right takes. You've still done no treatment, no balancing, no editing, no stereo placement, nothing like that. But at least now you have all the master takes compiled and ready for mixing."

Even more close listening follows, as Wilson lines up the original stereo mixes to compare them with the master-take multitracks. This is a slow, painstakingly intense part of the process. "I start listening to 10, 15 seconds at a time, and it'll be 'Oh yeah, the guitar's muted for those first four bars of the second verse, so I need to do that in my session.' Then I'll listen to the next 10 seconds, and 'Ah, OK, there's a phaser been added to the hi-hat there.' And so on through each song."

Apple's Logic has been Steven Wilson's sequencer of choice since before it was Apple's Logic!Usually, Wilson is dealing with detailed pieces of work, where the texture of individual sounds and their presence and location is just as important as any other constituent of the classic recording in question. "Some of these mixes were real works of art," he says. "They'd spend a couple of days, and there'd be three or four of them, all on the faders, bringing phasers in, bringing reverbs in on particular words, panning things left and right, riding solos or phrases in and out, that kind of thing. So listening on headphones and identifying all of these mix moves and where things have been muted or taken out of the mix maybe for a few bars — all of that takes the most time. That's the detective work. And it's so easy to miss things without full concentration."

Apple's Logic has been Steven Wilson's sequencer of choice since before it was Apple's Logic!Usually, Wilson is dealing with detailed pieces of work, where the texture of individual sounds and their presence and location is just as important as any other constituent of the classic recording in question. "Some of these mixes were real works of art," he says. "They'd spend a couple of days, and there'd be three or four of them, all on the faders, bringing phasers in, bringing reverbs in on particular words, panning things left and right, riding solos or phrases in and out, that kind of thing. So listening on headphones and identifying all of these mix moves and where things have been muted or taken out of the mix maybe for a few bars — all of that takes the most time. That's the detective work. And it's so easy to miss things without full concentration."

Finally, Wilson reaches the point where he can actually remix the track whilst remaining true to the artist's original vision: he stresses that his stereo remixes provide an enhanced version of the original and not a wholly new experience. His task to this end is often made easier by the clarity and exposure that the original multitracks can reveal, and then it's a case of making adjustments only where necessary. "At this stage in the workflow, it's a matter of refining," he says, "trying to get as close as possible to the original mix, tweaking EQs and so on. Over a period of days, I'll finish the mix, and then when I go back to it a couple of days later I'll hear things that aren't quite right. Usually the artist will have some feedback, too. Sometimes they'll have memories of how they did things, which is really useful. But," he adds with a smile, "mostly they don't remember much at all. Hopefully, then the artist will come up and listen, and maybe they'll have some more feedback based on listening to it in my studio."

At that point, with an agreed final stereo mix, Wilson either goes on to create the 5.1 mix, if that's part of the job, or he'll deliver a stereo mix if that's all that's required. The files are delivered as 96kHz, 24-bit WAVs, usually to whoever is mastering the CD or authoring the Blu‑ray or DVD.

Many of Wilson's remix projects involve surround mixes, for which a 5.1 monitoring system is vital.

Many of Wilson's remix projects involve surround mixes, for which a 5.1 monitoring system is vital.

History Channels

That's the broad outline of Steven Wilson's remixing work, from commission to completion. His primary tool for the job is Apple's Logic Pro, which he's used for many years, beginning back when it was still C-Lab Creator. Before that, he worked his way up from his teenage years, when his dad, an electronics engineer who worked for Nokia among others, built him a little multitrack cassette recorder and an echo box.

The first pro-level machine he owned was a Tascam 16-track tape recorder, which he had for a couple of years in the late '80s and early '90s, using it to record his early No-Man records with Tim Bowness and the first Porcupine Tree album. Soon after that he discovered ADAT machines and the world of early digital recording. "When I listen to my ADAT albums now, they have that signature of the early generation of digital recording, the opposite of analogue. At the time, I liked the clarity and silent noise floor after years of struggling with faulty analogue tape machines, but now, of course, they sound a bit harsh and cold, and I recognise that some of the beauty of sound is missing. Nowadays, digital recording has come a long way."

Steven Wilson: ""The guys in Apple in Hamburg that take care of Logic have become good friends, to the point that they actually changed some of the 5.1 implementation based on my suggestions."As for Logic, it could just as easily have been Pro Tools or Cubase, but his local dealer suggested C-Lab Creator. "The guys in Apple in Hamburg that take care of Logic have become good friends, to the point that they actually changed some of the 5.1 implementation based on my suggestions. I can't imagine being able to do that with most companies of that size. You'd think Apple of all companies would be the most impenetrable of all, but they've been fantastic. So I've been a Logic guy probably for more than 20 years now."

Steven Wilson: ""The guys in Apple in Hamburg that take care of Logic have become good friends, to the point that they actually changed some of the 5.1 implementation based on my suggestions."As for Logic, it could just as easily have been Pro Tools or Cubase, but his local dealer suggested C-Lab Creator. "The guys in Apple in Hamburg that take care of Logic have become good friends, to the point that they actually changed some of the 5.1 implementation based on my suggestions. I can't imagine being able to do that with most companies of that size. You'd think Apple of all companies would be the most impenetrable of all, but they've been fantastic. So I've been a Logic guy probably for more than 20 years now."

In fact, when people ask Wilson what instrument he plays, "I tell them that for me, the studio has always been the instrument. I'm not that interested in playing or being a musician — I just love being in the studio, messing about. The studio, that's my instrument. It's that Eno thing, you know?"

In The Round

Wilson's introduction to the idea of surround remixing came when Elliot Scheiner created 5.1 remixes of the Porcupine Tree albums In Absentia and Deadwing, in 2004 and 2005 respectively. "Being the control freak that I am," Wilson says with a smile, "I started to feel that this was something out of my control. I wanted to be able to do it myself. There were some mix decisions that Elliot made that weren't the way I would have approached it. But I didn't have the skills, or the technology at the time, to be able to do it myself."

So Wilson taught himself how to make surround mixes. The next Porcupine Tree album, Fear Of A Blank Planet (2007), came out with a Wilson surround mix. "And it got a Grammy nomination for best surround sound mix! So I thought wow, I must be doing something right."

This led to Wilson's first remix for a band other than his own, on King Crimson's In The Court Of The Crimson King. At the time, King Crimson and Porcupine Tree shared the same management. Like any good managers, they asked Robert Fripp if he'd be interested in their Grammy‑nominated client making remixes of the Crimson catalogue. "I guess it was a perfect storm," Wilson says. "I wanted to get more involved in remixing, and I think they were looking to revamp the catalogue with anniversary editions and so on." Wilson duly made a new 5.1 and a recreated stereo mix for the Crimson King box that came out in 2009, on the album's 40th birthday.

Buried Treasure

Wilson's first crack at remixing for another artist was also his first experience of finding alternative takes and unheard versions among the multitracks, which can form part of the draw for fans who always want to hear that little bit extra from the archive. Wilson's personal preference is to find new songs or completely alternative treatments of songs, rather than simply alternative takes. On Crimson King he found a haunting version of 'I Talk To The Wind' with just Fripp on guitar and Ian McDonald on flute. "That was a beautiful instrumental," he says, "and a completely different piece, really, not just another take of what we already know. To me, alternate takes are not so interesting, though I understand there are people out there who would happily listen to a whole disc of studio run-throughs of '21st Century Schizoid Man'. What I'm excited by is when you find a performance that actually adds something new to the canon."

Then there are pieces that benefit from the clarity afforded by a modern mix and digital format. For instance, the final 10 minutes or so of 'Moonchild' from Crimson King are very quiet indeed. "If you listen to the original mix, you're literally listening through a wall of tape hiss," Wilson says. "It's like the tape hiss is louder than anything going on in the song! And so that was one of the nice things we were able to do with the remix. I got that noise floor right down — not completely, but now you can hear a lot more of what they're doing."

Then there are pieces that benefit from the clarity afforded by a modern mix and digital format. For instance, the final 10 minutes or so of 'Moonchild' from Crimson King are very quiet indeed. "If you listen to the original mix, you're literally listening through a wall of tape hiss," Wilson says. "It's like the tape hiss is louder than anything going on in the song! And so that was one of the nice things we were able to do with the remix. I got that noise floor right down — not completely, but now you can hear a lot more of what they're doing."

Fripp is a musician who revels in intelligent observations, and Wilson recalls one in particular concerning the Crimson King album. "He told me that he believed the traditional notion of genius is wrong: this idea that there are certain artists in the world who are musical geniuses. He believes that genius is something that visits people temporarily and then moves on. In 1969, he said, King Crimson were temporarily visited by the spirit of genius, and they made that one record. He wasn't saying all their other records aren't good too, but he said that record had the magic. And then the spirit of genius moved on, maybe to Pink Floyd, who did Dark Side Of The Moon, or whoever it was took the next step into creative genius. That's a really interesting point. Because I think there's no artist who hasn't made at least one below-par record, so how does that square with the notion of them as a genius?"

Lung Transplant

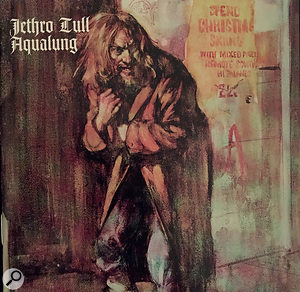

Steven Wilson has remixed much of Jethro Tull's back catalogue, and Aqualung in particular was an album that cried out for a remix. Wilson knew the original well and remembered how muddy and hissy it was, with some weird frequency issues going on. Popular opinion seems to agree with his own view that his remix fixed many of those sonic problems. And here's the paradox: it sounds better; but perhaps also it's a little more clinical.

Steven Wilson has remixed much of Jethro Tull's back catalogue, and Aqualung in particular was an album that cried out for a remix. Wilson knew the original well and remembered how muddy and hissy it was, with some weird frequency issues going on. Popular opinion seems to agree with his own view that his remix fixed many of those sonic problems. And here's the paradox: it sounds better; but perhaps also it's a little more clinical.

"That's almost inevitable," he says. "Honestly, to me, bearing in mind I don't know a lot about analogue tape, it sounds like the original was mixed on to a faulty machine or a machine that wasn't lined up properly. And it's always sounded a bit like that: very muffled and hissy. I was able to fix that, because the source multitrack tapes sounded beautiful. The remix has clarity missing from the original, it sounds beautiful, and to some it's the definitive mix now. But understandably, other people would probably still rather hear the original analogue mix with all its flaws. I accept that. That's not something that can ever be reconciled with a remix project, which is why I always try to encourage the record company to include both the original and the remix on a reissue set, as two different experiences."

Many of the Tull records that Wilson has remixed provided an unusually rich seam of unreleased or little-heard songs. In his estimation, the Tull tapes generally reveal at least twice as many songs as were selected for the final album. With Aqualung, for example, there was enough for an entire disc of such material, most of which was in an almost-finished state. "The Tull series has been a lot of fun," he says, "finding all these completely unreleased songs that even Ian can't remember recording. Apparently they quite often went into the studio, recorded a song, and then literally forgot all about it — didn't even mix it!"

Topographic Equalisation

This original track sheet from the 'Sound Chaser' multitrack indicates the degree to which Yes pushed the limits of 24-track recording.Wilson has so far remixed five Yes albums, and he's particularly pleased with the results on Tales From Topographic Oceans, a recording that has had its critics since it was released in 1973. You'll recall that it's the one with four long pieces spread over four sides of the original double vinyl album. "I was happy with what I achieved with that one and with Relayer, because I don't think those albums sounded sonically as good as the earlier ones," he says. "I've tended to most enjoy working on albums that perhaps had some kind of problem with the original mix. So I figured OK, now that we're remixing, we can maybe fix some of those things."

This original track sheet from the 'Sound Chaser' multitrack indicates the degree to which Yes pushed the limits of 24-track recording.Wilson has so far remixed five Yes albums, and he's particularly pleased with the results on Tales From Topographic Oceans, a recording that has had its critics since it was released in 1973. You'll recall that it's the one with four long pieces spread over four sides of the original double vinyl album. "I was happy with what I achieved with that one and with Relayer, because I don't think those albums sounded sonically as good as the earlier ones," he says. "I've tended to most enjoy working on albums that perhaps had some kind of problem with the original mix. So I figured OK, now that we're remixing, we can maybe fix some of those things."

His aim on these two albums was to give them more sonic richness and clarity, more definition, and to make them a little less harsh to listen to. "Topographic Oceans was a particular challenge, with these huge 20-minute pieces of music which were recorded on 24 tracks — because what Yes were reaching for was something way beyond the capabilities of 24-track tape. I'd be taking one channel in isolation on a 24-track tape and, for example, it might start off as a percussion part, then there'd be a little bit of bass, then a backing vocal would come in, and then a guitar overdub, then it would go back to the percussion. And every track of the multitrack was like that. They were cramming every inch of every channel on this 24-track tape. If Yes had had the limitless possibilities of digital recording available to them, they'd probably have gone even further with their vision."

His aim on these two albums was to give them more sonic richness and clarity, more definition, and to make them a little less harsh to listen to. "Topographic Oceans was a particular challenge, with these huge 20-minute pieces of music which were recorded on 24 tracks — because what Yes were reaching for was something way beyond the capabilities of 24-track tape. I'd be taking one channel in isolation on a 24-track tape and, for example, it might start off as a percussion part, then there'd be a little bit of bass, then a backing vocal would come in, and then a guitar overdub, then it would go back to the percussion. And every track of the multitrack was like that. They were cramming every inch of every channel on this 24-track tape. If Yes had had the limitless possibilities of digital recording available to them, they'd probably have gone even further with their vision."

On songs like 'Ritual', Yes squeezed far more than 24 instruments onto 24 tracks; modern DAW recording gave Steven Wilson the luxury of being able to separate out all of these elements onto their own Logic tracks.Wilson describes Topographic as fantastically ambitious, but he knows that must have made it a nightmare to mix originally. "So I come along 40 years later, and of course I can load up the 24-track original and split out everything on to its own channel. So a 24-track tape ended up being maybe an 80-channel session, because I've given every little piece its own track. And that means I can treat each of those parts with its own EQ, its own compression, reverberation, treatment and placement. In that way, I was trying to get a little more out of it than they possibly could in the original mix."

On songs like 'Ritual', Yes squeezed far more than 24 instruments onto 24 tracks; modern DAW recording gave Steven Wilson the luxury of being able to separate out all of these elements onto their own Logic tracks.Wilson describes Topographic as fantastically ambitious, but he knows that must have made it a nightmare to mix originally. "So I come along 40 years later, and of course I can load up the 24-track original and split out everything on to its own channel. So a 24-track tape ended up being maybe an 80-channel session, because I've given every little piece its own track. And that means I can treat each of those parts with its own EQ, its own compression, reverberation, treatment and placement. In that way, I was trying to get a little more out of it than they possibly could in the original mix."

Picking Up The Pieces

At the time of writing, Wilson's 5.1 remix of Seeds Of Love by Tears For Fears is awaiting release some time in 2019, its 30th anniversary year. It has been his most complicated remixing job so far. It's also one of his favourite records of all time. "In terms of '80s production, it's the very pinnacle for me," he says. "Yes, there's a lot of digital reverb on it, and yes, there's a lot of '80s synthesizers on it, but the songwriting, the craftsmanship, the production, the engineering and the mixing are flawless." Which explains why Wilson only did a 5.1 remix: it would be pointless, he says, to try to improve on the original stereo mix.

The original recording, too, was anything but straightforward. It took Roland Orzabal, Curt Smith, and their collaborators around three years to complete. And this complexity feeds into Wilson's story, too. "They used different studios, tried different musicians, made different takes, had different engineers, and so when we came to consider the multitrack tapes, there were many problems." Some of the songs were recorded with three 24-track tape machines running in sync, essentially a master and two slaves, resulting in up to 72 tracks of recorded information.

The original recording, too, was anything but straightforward. It took Roland Orzabal, Curt Smith, and their collaborators around three years to complete. And this complexity feeds into Wilson's story, too. "They used different studios, tried different musicians, made different takes, had different engineers, and so when we came to consider the multitrack tapes, there were many problems." Some of the songs were recorded with three 24-track tape machines running in sync, essentially a master and two slaves, resulting in up to 72 tracks of recorded information.

"Not only that," Wilson adds, "but some of the tracks were recorded over a long period of time. Sometimes the takes had been cloned, and then certain things had been replaced. For example, one take had been copied, and then a different drummer had come in and overdubbed his drums over the top of somebody else's drums. So you might think you've got the right slave tape for, say, 'Year Of The Knife', and then you load it up. You hear the bass part's right, the synth part's right, the vocals are right, but, oh dear, that's a different drum take. Ah, we need to find a different slave reel with a different drum performance on it but all the other stuff the same."

Tears For Fears' Seeds Of Love album has proved to be Wilson's most complex remix project so far.

Tears For Fears' Seeds Of Love album has proved to be Wilson's most complex remix project so far.

To cut a very long story short, they never found all the right parts. "So, for example, the drum mix for 'Woman In Chains', which is Phil Collins, we never found the correct drum multitrack slave — it's just a stereo bounce-down from one of the other reels. That's all I had to work with. Not ideal, but when you've asked the record company to bake another 10 or 20 tapes, and you've been back four or five times, and it's costing them an arm and a leg every time, you get to the point where they say 'Sorry, we can't bake any more tapes, you're just going to have to piece it together with what you've got.'"

And that's what Wilson did, using what he estimates as 95 percent of the material he sought, and pushing forward with the help of the original engineer, David Bascombe. "In one case, I had to take the first five seconds of 'Sowing The Seeds Of Love' from the original stereo tape, those static sounds of radio tuning that I could have had a lot of fun with in surround. I couldn't find that on any of the multitracks. We tried going to Roland's personal tape store, but it was nowhere to be found, and nobody remembered where it had come from. So I took it off the original stereo master tape, and of course then you can't do anything with that in surround, you're just stuck with stereo. But," he says with a laugh, "it's just a few seconds."

For The Fans

An important consideration for Wilson when he's creating remixes is the audience. Perhaps that's obvious, and yet there are other remixers who seem to work for themselves rather than anyone else, who seem to take too many liberties with the original. Wilson has the benefit of being a musician, a fan, and a performer, alongside his deep love of recording. "My approach probably doesn't sit well with everyone, though," he says. "I've seen comments from people where they say they've bought a Steven Wilson remix expecting something radical, but it sounds the same. But to other people, that is the point. It's the same as they remember, just with a bit more clarity and so on. I saw a comment about my Chicago II remix saying what was the point if it's so faithful to the original? Well, you would hear a significant difference in the sonics if you compared them against each other. But ultimately, on the surface, it's not supposed to sound different."

Wilson says he's acutely aware of who he's doing these remixes for, of who's going to listen to them and what they want from them. "I'm primarily doing them for the people who already know and love these records. It would be wonderful to think there's a potential new audience that might appreciate something because it's been remixed and made to sound a bit vivid for modern listening. But I think 99 percent of the audience are people who have bought these records at least once before, if not three or four times."

The artist can be an important contributor to the process. "They have the prerogative, of course, to change their own work," Wilson says. "You don't want to mess with someone else's vision, but all the same I think often it's better that the artist isn't too closely involved in the project, at least during the main mixing process."

One artist refused to include a version of a classic track with seven or so minutes of the band improvising beyond the original fade; another vetoed an out-take because he hadn't written it. Wilson has to be a diplomat in addition to his technical duties.

He sums up his approach as being devoutly faithful to the original mix when he's working in stereo, and creating something fresh when he's working in surround. "When you're working in digital and remixing — at very high resolution, I should say, from beautifully transferred copies of the analogue tapes — then detail that wasn't there before will come out anyway, almost without necessarily changing anything. Suddenly, you hear things that you didn't hear before. When you get to surround sound, that's even more the case, because you have this space and these extra dimensions. Now you can hear things that you would never have heard in stereo. There's a whole psychology going on with the way people connect with remixing. It can be quite controversial, and I think if I've achieved anything, I've minimised the controversy by doing something that people can at least appreciate, even if they would still rather hear the original mix."

Work Work Work

We leave Wilson with his sixth solo album to write and record, a slew of further live shows to perform, a Blu‑ray DVD of a recent Albert Hall date set for release, and various remixes in the works, including the next in his series for both Jethro Tull and XTC, plus a boxed set of Tangerine Dream material set for release with his 5.1 remixes of Phaedra, Ricochet and an unheard 1974 album. "Just use your ears," he concludes. "It doesn't matter if it's not perfect, or if you don't really know how or why it works. The question has to be: does it sound good? I didn't go to audio school, I never learned how to to use any of this stuff. I just messed about until it sounded good."

Familiar Failings

Steven Wilson recalls a conversation with Allan Rouse, the engineer who curated the 2009 Beatles remasters, about the degree to which mistakes should be corrected. Rouse and the team had to ask themselves questions about seemingly minor things such as clicks and pops and hums and other ephemeral noises that were part of the original recordings. Should they clean them up? "He told me it was six of one and half a dozen of the other," Wilson says. "Some they decided they should remove, some they decided it was best to leave, because they had become part of the fabric of the song. You just have to follow your own instincts. And because I have an affinity with these records, I think I have a good instinct for knowing what I should fix and what I shouldn't."

A case in point arose on his remix of Marillion's 1994 album Brave. At one point, two songs are crossfaded together, but this hadn't been done too well on the original release. "The final note of the previous song was supposed to hit the first note of the second song, and in the original it missed. I asked myself, 'Should I fix that?' At first I fixed it, but then I decided no, I should put it back to how it was, because that's the way people have been listening to it for 25 years. It's no longer a mistake: it's become the way it is. For every person who complained that I didn't fix it, there would have been someone who'd have said, 'How dare he change that? Sacrilege!'"

There have even been instances where the artist has asked Wilson to change things and he has been resistant. "One said to me 'Oh, when we played that in the studio, we played it too slow. Can you speed it up?' I said 'No! I'm not going to do that. This is a classic album, and whether you're happy with it or not, this is like a sacred text. I'm not going to change it.'"

Virtual Vintage

The availability of good plug-in recreations of vintage gear makes Steven Wilson's job a lot easier, as here on Jethro Tull's 'Aqualung'.

The availability of good plug-in recreations of vintage gear makes Steven Wilson's job a lot easier, as here on Jethro Tull's 'Aqualung'.

The biggest move forward in technological capability in recent years for Steven Wilson's remixing work has come with plug-ins that recreate vintage studio effects. These make it easer to get sounds in the digital domain that are closer to the original analogue effects used on many classic records.

"I'm using a lot of the Universal Audio plug-ins, which are fantastic emulations of original analogue stuff. Now I'm able to use emulations of a lot of the old analogue compressors, like the Fairchild or the 1176, and the EMT 140 plate — many of the things they were using at the time. The last couple of years I've been adding the UA Oxide Tape plug-in to the output bus, too, which definitely seems to give things a little more of that analogue magic."

The Steven Wilson Remix Catalogue

| Album | Original release year | Remix release year | Format |

| Chicago | |||

| Chicago II | 1969 | 2017 | Stereo only |

| Gentle Giant | |||

| Three Piece Suite | 1970–71–72 surviving multitrack tapes of first three albums. | 2017 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Octopus | 1972 | 2015 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| The Power And The Glory | 1974 | 2014 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Jethro Tull | |||

| Stand Up | 1969 | 2016 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Benefit | 1970 | 2013 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Aqualung | 1971 | 2011 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Thick As A Brick | 1972 | 2012 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| A Passion Play | 1973 | 2014 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| War Child | 1974 | 2014 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Minstrel In The Gallery | 1975 | 2015 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Too Old To Rock & Roll: Too Young To Die! | 1976 | 2015 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Songs From The Wood | 1977 | 2017 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Heavy Horses | 1978 | 2018 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| King Crimson | |||

| In The Court Of The Crimson King | 1969 | 2009 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| In The Wake Of Poseidon | 1970 | 2010 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Lizard | 1970 | 2009 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Islands | 1971 | 2010 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Larks' Tongues In Aspic | 1973 | 2012 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Starless And Bible Black | 1974 | 2011 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Red | 1974 | 2009, 2013 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Discipline | 1981 | 2011 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Beat | 1982 | 2016 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Three Of A Perfect Pair | 1984 | 2016 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Marillion | |||

| Misplaced Childhood | 1985 | 2017 | 5.1 only |

| Brave | 1994 | 2018 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Roxy Music | |||

| Roxy Music | 1972 | 2018 | 5.1 only |

| Rush | |||

| A Farewell To Kings | 1977 | 2017 | 5.1 only |

| Simple Minds | |||

| Sparkle In The Rain | 1984 | 2015 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Tears For Fears | |||

| Songs From The Big Chair | 1985 | 2014 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| XTC | |||

| Drums And Wires | 1979 | 2014 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Black Sea | 1980 | 2017 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Skylarking | 1986 | 2016 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Oranges & Lemons | 1989 | 2015 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Nonsuch | 1992 | 2013 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Yes | |||

| The Yes Album | 1971 | 2014 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Fragile | 1971 | 2015 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Close To The Edge | 1972 | 2013 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Tales From Topographic Oceans | 1973 | 2016 | Stereo & 5.1 |

| Relayer | 1974 | 2014 | Stereo & 5.1 |