Drum & bass phenomenon Wilkinson tells us how his live show evolved from a simple DJ setup to a seven-piece band.

Hailing from the leafy suburbs of South-West London, Wilkinson is an underground drum & bass producer who has crossed into the commercial charts and Radio One playlists, thanks to his ability to pair compelling songs with flawless production. His first insight into making music came at just nine years old, when he began drumming in a band with his present-day guitarist Tom Varrell. At 14, Wilkinson's aspirations to be in a band ended when he discovered his passion for dance music. After fine-tuning his now legendary production skills, Wilkinson sent a folder of tunes to RAM Records, whereupon label founder and drum & bass legend Andy C signed him in 2010. It was through RAM/Virgin EMI that he put out his 2013 debut album Lazers Not Included, which went to number 1 on the iTunes Dance Chart in 10 countries, followed shortly afterwards by his breakout track 'Afterglow', which became a top five hit in the UK, selling 500,000 copies and attracting 65 million YouTube views. His schedule exploded.

"I was put in the position where I was being asked to play Radio 1 Big Weekend and big festival bookings, and I was playing between bands," says Wilkinson. "From watching the other bands and seeing all of the effort that went into the live process I knew I wanted to be a part of that, and take on that challenge." In April 2017, Wilkinson released his follow-up album Hypnotic, which became the most successful drum & bass album of the year and was in the top 20 iTunes albums across six countries.

Transforming a dance music album into a successful live show, one that integrates technology with a band of live musicians, is a considerable challenge. There are successful bands like the Prodigy, Pendulum and Chase & Status who have done this before, but due to the pace at which technology and production styles change, there are still significant challenges, and many different ideas about how it should be done. With few forerunners in the drum & bass genre to learn from, Wilkinson had to work out a successful formula for his live show from the ground up. Wilkinson explains how the live show links to his last album Hypnotic: "The thing I was aiming for with my second album is to demonstrate a chapter of where my production has got to. My first album was a very club‑orientated chapter, whereas this album was me pushing what I could do with vocals and euphoric synths, and also exploring new tempos. My journey is to push high‑energy dance music, to be able to go on stage at a festival and be 10 times louder than the other bands. I want my live shows to be amongst DJ sets, and if you go on after a DJ who has been tearing it out then this has to stand up. It's about who can make the crowd go as wild as possible, and that's the challenge here for the live setup. When the sonics are on point and we have made everything sit together so perfectly, and we haven't got loads of dynamics jumping around, we can push the overall level higher than anyone else."

First Steps

Initially Wilkinson started DJ'ing with a live vocalist; then, in 2015, he found live sound engineer and musical director Pete Thomas, and together they started working on expanding the live show, putting more and more elements in the hands of live musicians. As Wilkinson explains, it's been a gradual transformation: "We went through a process of me playing with a vocalist as the only live element, to me playing some samples with drums, guitar, and vocals on the Lazers Not Included tour, to now where it feels like I am in the studio playing all the elements."

Wilkinson's current band line-up is Wilkinson on keyboards and sample triggers, Tom Varrell on guitar, Alex Todd on acoustic and electronic drums, and Jem Cooke, Shannon Saunders, Simon Youngman Smith and Adam Brown aka Ad-apt on vocals. Anything that can't be performed live comes off a backing track courtesy of an Ableton Live rig. "I love the sound of acoustic drums in a live band, and for me, the fundamental core of a band is drums, guitar and either bass or keyboard; it's a three‑piece band that I wanted to create. When I started the live show, a lot of people told me, 'Your music is going to change, you're going to become one of these electronic acts that starts putting guitar on all your tracks.' But I could see, with the technology around, a way to write the record and then make what we do replicate the record, not the other way round. For example, if I have a song with no guitar on, I will get Tom to play the synth line, because he can make a guitar sound like any synth sound."

Although some artists can be secretive about the way their live shows are put together, that's not the case for Wilkinson: "I've never taken apart the show in an interview before, and people I've worked with are like, 'Don't tell anyone what you're doing,' but I am proud of the fact we have spent so much time on it and have built it all from the ground up. A lot of people just go up and mime on stage, but I want people to understand the time and effort we have put into this. When I do a DJ set it's just an SD card and my tour manager, but a full band setup costs me £20,000 per show. I'd like to know that people identify the difference between them and appreciate that the live set is the purest form they will hear the tracks in, and that's quite special. That's what I want to really get across."

Pre-production

Taking a break from a full show rehearsal, Wilkinson and his MD Pete Thomas discuss their approach to preparing the show.

Pete Thomas: "Last November we came up with the idea to approach the live set by recreating a Wilkinson DJ set."

Wilkinson expands: "The whole idea of the set is that I come from a club/DJ environment, and what I wanted to do was have a live show that doesn't stop and start like a normal band. I wanted it to be like a drum & bass DJ set; for example, when I'm DJ'ing I will double-drop a track with another track, or create seamless transitions from one track to the next. One of the key things for creating a good transition is that is you make sure you go from a song in C to another song in C or A minor."

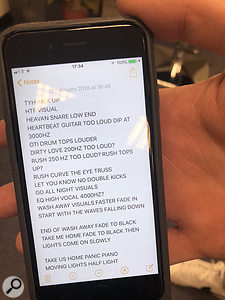

Wilkinson keeps meticulous notes from the band's rehearsals.Pete: "Wilkinson made a DJ mix of all of his songs, and that's the first time we attempted to start building it from that angle. Before that, the standard was to look at it as set lists. Once the DJ mix was done we knew exactly how the live show needed to sound, and that really set the bar a lot higher than it had ever been before."

Wilkinson keeps meticulous notes from the band's rehearsals.Pete: "Wilkinson made a DJ mix of all of his songs, and that's the first time we attempted to start building it from that angle. Before that, the standard was to look at it as set lists. Once the DJ mix was done we knew exactly how the live show needed to sound, and that really set the bar a lot higher than it had ever been before."

Wilkinson: "We set ourselves a challenge, and we needed to start in November to have four months' preparation, because it wasn't just learning a song, it was learning every single transition — the transitions in the songs but also the transitions between songs, the patch changes, and refining the technology that controls it."

Pete: "If you're bringing one song into another song, you would normally crossfade those like a DJ would. However, to recreate this with a live show, to create transitions means working out which guitar, synth and drum patches you hold on to and for how long, and thinking about how best to recreate the effect of the smooth crossfade. I've been working on live music at a high level for years but it's the first time I've worked with someone who's insistent that we get all the live elements sounding exactly like the record. That's felt like quite a challenge."

The refinement process never stops, and Wilkinson shows his notes from the final rehearsal before the tour commences, requesting amendments for the sonics of the set. "I was front of house earlier listening to the guitars and drums, and I've got notes on my phone that would be gibberish to most people."

From left: MIDI tech Ben Nelson, Wilkinson, and musical director/FOH engineer Pete Thomas.

From left: MIDI tech Ben Nelson, Wilkinson, and musical director/FOH engineer Pete Thomas.

The Deep Dive

Having covered the background to the show in the dressing room, Wilkinson, Pete and MIDI tech Ben Nelson take us to the stage to talk us through each instrumentalist's rig and the backing-track technology that underpins the show. At the centre of the technical setup is a carefully constructed Ableton rig (see 'Backing Track Rig' box for details). The Ableton project is the entire live show laid out in Session View, with markers embedded at the start of each song. When rehearsing, this allows Ben Nelson to quickly trigger the backing track from any song marker. For the most part, when performing live, the set is run from the start to the finish. However, Ben has a few manual stops to perform. Looking at the project screenshot, there are different types of tracks coming from the Ableton project. Let's start with the backing tracks: these are there to support the live instrumentation and include bass, backing vocals, music effects and a drum track.

"The one element that we always leave on the backing track is the bass, because it's the thing that you can't replicate," says Wilkinson. "The sub levels have to be so perfect, and if they fluctuate at all, the kick drum starts to sound really loud and you lose the sonics that make it so thick and work so well. I could never replicate that live, so what I do on some tracks is play the modulating bass sound over the top of the sub. When I'm writing I always have a sub and write a bass on top of that and then separate them in the mix."

The percussion tracks also play a key role, says Pete. "With the drums there's a little bit of percussion on the backing track because you can't fill it all in with one drummer, and with drum & bass there's a lot of other percussion that accompanies the main break."

Even with four vocalists on stage, there's still room on the Ableton session for pre‑recorded backing vocals, says Wilkinson. "For example, when doing songs like 'Afterglow', which featured vocalist Becky Hill, Jem sings that on tour with us, so Jem reworked all of the backing vocals and stabs to support her sound in the mix. So when she sings on there it sits right and sounds really full and beds everything in correctly. If you have one element that doesn't sit right, it can make the whole thing sound strange".

Don't Panic

The Ableton project also contains 'panic tracks'. These are just audio recordings of a performer's parts, so that if any performer's rig catastrophically fails during the set then their panic track can be unmuted until the problem is fixed. "All of the drums that came off the record are there in the Ableton project, but muted," explains Pete. "Then if for any reason we lose the drums from stage, we can throw that back into the mix." There is also a timecode track: the Wilkinson show is an audio‑visual experience and so the synchronisation of audio, lighting and visuals is critical to the performance.

The backing and 'panic' tracks for the whole set are prepared in a single Ableton Live project. Here you can see the Session View, with markers at the start of each song.

The backing and 'panic' tracks for the whole set are prepared in a single Ableton Live project. Here you can see the Session View, with markers at the start of each song.

There are further significant advantages to using Ableton for playback over a more old‑fashioned multitrack. Ableton is a DAW with on‑board instruments and third‑party plug‑ins, and these can be integrated into a keyboard player's rig to provide a huge sound library of patches to choose from. Patch changes for on‑board and external instruments can then be drawn into the Session View timeline alongside the backing tracks, freeing Wilkinson up from having to manually change patches for different sections of a song.

Wilkinson and Ben take us through Wilkinson's keyboard rig and how it integrates with the Ableton project. On a basic level, the rig consists of a Roland Juno for general keyboard sounds, a set of drum pads for triggering one‑shot samples, a Novation Launch Control MIDI controller for manipulating effects, and a Novation Bass Station synth plugged into a Strymon Big Sky reverb pedal for leads. Wilkinson explains the history of the rig: "Originally I started off just DJ'ing, then I added triggering samples on the pads, then everyone was pressuring me learn to play the piano. I'm a studio guy, I use a lot of samples and I've never been taught piano, so I had to spend months and months learning to play the piano."

Wilkinson's drum rack, which he uses to trigger one-shot samples.The electronic drum pads are the oldest part of Wilkinson's live rig, and he uses them for playing simple melodies by triggering different one-shot audio samples. The electronic drum pads send MIDI into an Ableton instrument rack. The instrument rack is used as a container for hosting multiple drum racks, and a drum rack is used to lay out the sounds for one song or one section of a song. When preparing a song, Ben will drag an empty drum rack into the instrument rack and then populate the drum rack with the samples that Wilkinson will play during that song. The patch changes of the instrument rack are then added in Session View, so that when the backing track plays for a song the correct drum rack is chosen. Check out this month's Ableton Live workshop to see how you can set this up for yourself.

Wilkinson's drum rack, which he uses to trigger one-shot samples.The electronic drum pads are the oldest part of Wilkinson's live rig, and he uses them for playing simple melodies by triggering different one-shot audio samples. The electronic drum pads send MIDI into an Ableton instrument rack. The instrument rack is used as a container for hosting multiple drum racks, and a drum rack is used to lay out the sounds for one song or one section of a song. When preparing a song, Ben will drag an empty drum rack into the instrument rack and then populate the drum rack with the samples that Wilkinson will play during that song. The patch changes of the instrument rack are then added in Session View, so that when the backing track plays for a song the correct drum rack is chosen. Check out this month's Ableton Live workshop to see how you can set this up for yourself.

The instrument rack for the pads also has a series of effects assigned to it, which are controlled by a Novation Launch Control XL located next to the pad rack. Wilkinson uses this to fade up reverb or delay effects to create a transition from one track into the next: "I use the Launch Control to blend the song that I'm playing into the breakdown, making the transition into the next song less abrupt and more like one continuous mix, like a drum & bass DJ set."

The Ableton rig also has an instrument rack full of sounds that have been resampled into Simpler and Sampler keyboard patches, and which are triggered by Wilkinson's Novation Bass Station keyboard. MIDI tech Ben explains that they resample all Wilkinson's virtual instrument patches to sampler instruments, avoiding using third‑party plug‑ins inside the Ableton project. This approach helps Ben to ensure the Ableton project uses only a fraction of the available CPU cycles, which is critical to the stability of the rig — impressively, Ben has optimised the whole Ableton project to use no more than 16 percent of the CPU at any point in the show.

The Novation Bass Station isn't just used as a controller: Wilkinson alternates between using it as a MIDI controller and a synth in its own right. "The Bass Station alternates between being a MIDI controller for an Ableton rack and its own synth," explains Ben. "When we want to use the Bass Station as a controller we switch it to the zero patch, which outputs no sound. When the Novation is used as a synth in its own right then I send a patch change from Ableton to the correct preset."

Patch changes for Wilkinson's keyboards and drums are automated in Ableton Live. Here we see the track for Wilkinson's electronic drum pad rack; the Chain Selector automation switches patches in the Ableton instrument rack.The majority of Wilkinson's main keyboards sounds, however, come from a Roland Juno‑DS, with the Ableton project sending patch changes to it. Wilkinson: "With the Juno we make different patches for different sections of the songs. So for example, in 'Afterglow', there's the main piano and the high‑pass‑filtered piano for the verses. The thing that's cool about the Juno is you've got the effects utility, where you can load in three effects, and once you get your head into it you can replicate any sound."

Patch changes for Wilkinson's keyboards and drums are automated in Ableton Live. Here we see the track for Wilkinson's electronic drum pad rack; the Chain Selector automation switches patches in the Ableton instrument rack.The majority of Wilkinson's main keyboards sounds, however, come from a Roland Juno‑DS, with the Ableton project sending patch changes to it. Wilkinson: "With the Juno we make different patches for different sections of the songs. So for example, in 'Afterglow', there's the main piano and the high‑pass‑filtered piano for the verses. The thing that's cool about the Juno is you've got the effects utility, where you can load in three effects, and once you get your head into it you can replicate any sound."

The Drums

Wilkinson and his drummer Alex Todd have a unique approach to ensuring the drums are performed live but still sound like the record. The drum setup consists of an acoustic kit combined with electronic triggers going into a Yamaha DTX drum brain. For tracks that make heavy use of drum breaks, Wilkinson will chop the drum break at the kick and snare and load those samples into the Yamaha DTX. These samples are then assigned to a mute group and are triggered from a separate kick trigger pedal and a Roland V-Drum mesh snare. Wilkinson explains: "This setup means Alex can trigger the sample with all of the processing that you would have on the jungle Amen break. You can't really replicate that with acoustic drums."

"There are a lot of people putting these breaks on backing tracks and then having a drummer playing over the top," adds Alex, "but all of the flamming and layering that occurs just doesn't sound right." He explains that they use the Yamaha DTX because of its bombproof reliability and its flexible EQ, which allows them to get the sound right at source — a key part of the Wilkinson ethos. "The good thing about the DTX is I can go into the edit view and if we have taken the snare off the record, but live it hasn't got the same depth or bite, then I can use the in‑built EQ to boost the highs, mids or lows to recreate that feeling."

Guitar Rig

Guitarist Tom Varrell explains his setup. "I use the Kemper Profiler head for the main guitar sound. This is so useful because it takes all of the patch changes over MIDI from the Ableton rig; I can have one amp profile for one part of the song and a completely different amp for another. It would be impractical to carry that many amps on tour." Tom also alternates between using the Kemper as an amp and using a DI to bypass the amp for less heavy sounds. The Kemper's on‑board graphic EQ helps nail the sound of the record. "That's the thing that's cool about the Kemper," says Wilkinson, "we can precisely EQ it."

Tom adds: "The thing about working with Wilkinson is it's like he knows exactly what frequency everything should be hitting in a song. I'll play something and think that's perfect, and Wilkinson will say 'Take out 500Hz and boost at 1000Hz.'"

After the amp, Tom has a pedalboard for all the effects; for example in 'Heartbeat' Tom uses a pitch-shifter for the pitch‑bend effects on the guitar. One of the effects Tom is a big fan of is the PandaMIDI Future Impact synth pedal: "It's like a newer version of the Deep Impact, but you've got a MIDI editor that's like a soft synth, so I will remake a sound from the record on it and then Wilkinson will come in and tweak it."

In The Mix

Pete explains how he approaches getting a great mix for every show: "The show needs to be self-mixed — we call it getting it right in the box, which basically means there's so much coming up on the mixing console that for me to start selecting a different reverb for different synths for each song would almost be an impossible task, so we have really pushed each bit of kit we have got to the limit in terms of what EQ's it's got and what reverb it has. For example, the drum samples that we load into the DTX drum brain come straight out of the songs' Logic or Ableton projects as samples, but they will be missing the mastering process, so we can use its onboard EQ to add some of that extra enhancement."

Wilkinson: "When I've made these tracks they've been mastered and they have gone through multiband compression and limiting stuff that on my computer at home might cause freezes. What we can't do is run things like Ozone in a live environment, because it will just crash."

Pete Thomas mixes the show on a DiGiCo console.

Pete Thomas mixes the show on a DiGiCo console.

Sound Of The Future

To get the new Wilkinson live show to where it is today has been a three‑year journey of trial and error that has taken a huge amount of work and preparation, but it's been well worth, it as Wilkinson recounts. "I realised just how far the show had come from the early years, when we were playing a festival in Hungary and our soundcards in their rack got dropped going through the airport. We didn't think anything of it at the time until we were one and a half songs into an hour and 15 minute set and we were left with just the live instruments and a Juno keyboard. We could still pull off the show though, and the crowd went crazy; at the end of the set the whole audience were singing along to 'Afterglow'."

The guys are far from resting, though. Wilkinson and Pete are constantly looking for ways to make the show even better. "We did a session of B-sides for the last album and we did those in a classic recording studio, The Pool, owned by Miloco," says Pete. "We had strings and a grand piano, it would be amazing to do more stuff like that."

"Unfortunately everything is restricted by money," says Wilkinson, "and we have already put so much into this show for Brixton. You've got 16 crew on the road, tour buses and trucks, and it's really expensive. You have to do what you can with what you've got."

Chatting to Wilkinson about the future of the live show, he says, "I kind of feel like when I write new music it's me trying to do something new that I haven't done before, or filling a gap in what I feel is missing from my sound. I felt like I wanted to do more club tracks, so I've recently done three new club tracks: 'Decompression', 'Rush', and 'Take It Up'. They refreshed the set, and it's so much more exciting now doing the live show. I feel like things move much faster now. I put out my first album in 2013 and Hypnotic in 2017... You can put out an album every one or two years now, as I think people's attention spans are getting shorter. At the moment I want to focus on releasing singles and pushing the live show and hopefully taking it to some new countries that I've never played before."

Backing Tracks

For large-scale shows like Wilkinson's, backing track setups generally consist of two identical playback machines, A and B, which run in sync. The theory is that if rig A goes down, an operator or automated switch can change to rig B, and because both rigs run in sync the change between playback machines won't be very noticeable to the audience.

As with most aspects of music technology, things progress with time: five years ago it was common to see artists touring with a pair of Alesis HD24 hard‑disk recorders (see www.soundonsound.com/people/kojo-samuel-musical-director), but now many artists have moved on to using laptops. Wilkinson's backing track rig follows this pattern, and comprises two MacBooks running Ableton Live. Each laptop has a MOTU 24Ao audio interface, which takes 16 channels of audio out on D-sub connectors. MIDI technician Ben Nelson then uses Radial SW8 Auto-Switcher boxes to jump between the A and B rigs; each Radial SW8 box can take up to eight inputs from the A and B rigs, but because Wilkinson's show requires 16 inputs, two Radical SW8 boxes are used. Ben makes use of the Radials' automatic switching capability by playing a steady state signal from a track in Ableton and feeding that into the SW8 — should the signal drop out, the SW8 will automatically switch to the B system and 'sound' an alarm.

MIDI tech Ben Nelson uses a Novation controller to trigger playback of different songs from Ableton song markers.

MIDI tech Ben Nelson uses a Novation controller to trigger playback of different songs from Ableton song markers.

Part of Ben's duties as MIDI tech are to start and stop the backing tracks and cue up the next song at the appropriate time. To control playback on both laptops at once, Ben uses a Novation Zero SL MkII plugged into an iConnect MIDI interface. The iConnect acts as a MIDI splitter, duplicating the MIDI output from the Novation so that the same MIDI messages can be sent to both MacBooks at the same time. The Novation MIDI controller is used to switch markers in the Ableton project. There are places in the set that have a dead stop; at these points the Novation is used to stop the backing track playback for as long as Wilkinson wants to engage with the audience. Then the Novation is used to jump to the next song and continue playback when Wilkinson is ready to restart, as Ben explains: "For example, there's a stop before the song called 'Rush', so I hit Stop, move to the next cue and restart playback when Wilkinson is ready".